The Real History of the End of the World (29 page)

Read The Real History of the End of the World Online

Authors: Sharan Newman

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

4.92Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In convincing people that a new order had come, Hong was helped by a non-Christian prophecy. A French chronicler living in China in 1850 noted that “Among the higher and middle classes of Pekin there is a firm belief in the prophecy diffused over China a century ago, that the reigning dynasty will be overthrown in the commencement of the 48th year of the present cycle, and this fatal year will begin on the 1st February next.”

19

19

Hong instituted rules for his followers: Everything was to be held in common, they were to obey the Ten Commandments as he had revised them, and they were to obey their officers “in a harmonious spirit” and never retreat in battle until ordered. The last rule was that men and women were to stay celibate and apart, the women fighting in their own units.

20

20

It was clear that Hong was preparing for a removal to the real heaven once his people were purified enough. But the twelve years of the Heavenly Kingdom were much like those of the British Interregnum under the Puritans. Added to the obvious problem that most people are not saints was the growing paranoia and arbitrary behavior of Hong. He often ordered executions for trivial offenses, something that always seems to go with absolute power. What was more worrying was his reliance on divine protection, rather than force of arms. When asked about creating defenses against a siege, he replied, “I, the truly appointed Lord, can, without the aid of troops, command great peace to spread its sway across the whole region.”

21

21

After several attempts, Issachar Roberts finally arrived in Nanjing, eager to start Christian schools there. He found Hong installed in oriental splendor. The Heavenly King explained to his old teacher that he had received new information directly from heaven. He expected Roberts to go out among the Westerners and preach the faith according to Hong. Roberts was horrified. It took him only a short time to realize that this was only a shadow of Christianity and that Hong could not be convinced of his errors. Bitterly disappointed, Roberts returned to America where he died later of leprosy, contracted during his earlier work at a leper colony in Macao.

22

22

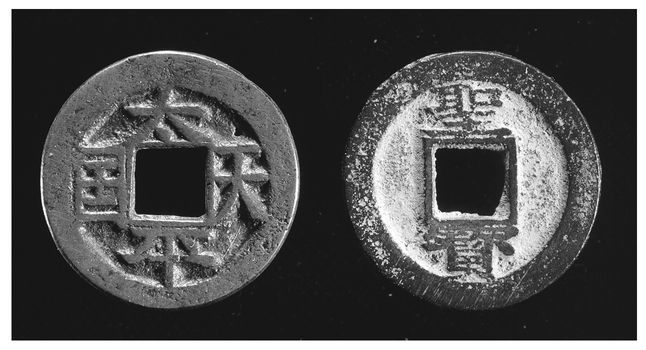

Brass cash coin of the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864). China, Qing dynasty, ca. 1850. The inscription on the front of this coin reads “Tai ping Tian guo.” (“Taiping Heavenly Kingdom”). The inscription on the back of the coin reads “sheng bao” (“sacred treasure”). This Heavenly Kingdom on earth was to be short-lived. The Taiping rebels were defeated by combined Chinese and European forces in 1861. Location: British Museum, London, Great Britain.

© The Trustees of The British Museum / Art Resource, NY

© The Trustees of The British Museum / Art Resource, NY

At the end, as the Heavenly Kingdom crumbled, Hong seems to have lost all contact with this world. In a poem penned in February 1861 he wrote:

Now there were four tigers, but all were killed and cast away,

And throughout the world, the officials and people rejoice at my victorious return.

To Heaven the road is open; the devil tigers are exterminated;

The oneness and unity of heaven and earth is arranged by Heaven.

23

23

For Hong, the millennium had arrived, and he had achieved divinity. He also wrote, “The Father, the Elder Brother, myself, and the Young Monarch [Hong's son] sit in the Heavenly Court; peace reigns over all the world, and the heavenly omens are fulfilled. The old, the young, men and women, all see the heavenly omens, and the Heavenly Elder Brother's earlier proclamations have now been realized.”

24

24

Instead of this idyll, the city was taken by Imperial forces. Hong committed suicide along with some of his followers. Several of the leaders were captured and made to write long confessions in which they detailed the makeup of the Heavenly Kingdom and their beliefs, but because the confessions were definitely intended to stave off execution, or at least make it less painful, they are sprinkled with negative adjectives.

25

25

The Taiping armies won followers in many provinces. For the most part, these converts joined for social and political reasons, rather than religious. But the core of the believers in Nanjing seem to have had a developed theology. They published a number of their own tracts, which still exist. These mainly stress the goodness of the Heavenly Father and his younger son, Hong. But they also dwell on the evils of the day: the oppression of the peasants; the problems with opium; the state of lawlessness; and the rule of the Manchu, foreigners who make men shave their heads in front as a sign of subservience. The people of China were offered the hope of change packaged in a way that promised happiness in this life and the next.

26

26

Perhaps if Hong had been more in touch with the world around him, the rebellion would have succeeded. The goals of equality among the faithful, land reform, and freedom from exploitation were the same as those of many revolutions that resulted in a permanent transfer of power, including that in China a hundred years later.

The Taiping armies were not a small regional force. They threatened Beijing and besieged Shanghai. The twelve years of war cost the lives of millions, either in battle or from disease and starvation. The winners were not the Chinese, but the Europeans, particularly the British, and the Americans, who sold guns to both sides but eventually decided to support the emperor in return for numerous trade concessions. In 1860, as their reward, the French and British took Beijing, burning the Summer Palace and looting the city. The French empress Eugenie was later presented with a pearl necklace from the collection of the empress of China.

27

Queen Victoria received a gold and jade scepter and the first Pekinese dog ever seen in Europe. She named it Lootie and kept it until its death in 1872.

28

27

Queen Victoria received a gold and jade scepter and the first Pekinese dog ever seen in Europe. She named it Lootie and kept it until its death in 1872.

28

The Taiping Rebellion has all the marks of a millenarian movement; a charismatic leader, a doctrine of spiritual salvation, the physical salvation of the elect, a radical change in the structure of society, and a strict set of rules to be followed for the believer to prove genuine conversion. In the beginning, Hong had plans for building a real heaven on earth. This may have been thwarted by his increasing madness or it may have been that earth and heaven were just too far apart.

1

Vincent Y. C. Shih,

The Taiping Ideology: Its Sources, Interpretations, and Influences

(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972), 20.

Vincent Y. C. Shih,

The Taiping Ideology: Its Sources, Interpretations, and Influences

(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972), 20.

2

In the course of this article, the Chinese names are spelled in different ways in the quotations, reflecting changes in standard ways of rendering them in English. So, Hong Xiuquan is the same as Hung Hsiu-ch'uan, for example.

In the course of this article, the Chinese names are spelled in different ways in the quotations, reflecting changes in standard ways of rendering them in English. So, Hong Xiuquan is the same as Hung Hsiu-ch'uan, for example.

3

See the section on The Yellow Turbans.

See the section on The Yellow Turbans.

4

Jonathan D. Spence,

The Taiping Vision of a Christian China 1836-1864

(Waco, TX: Baylor University, 1996), 6.

Jonathan D. Spence,

The Taiping Vision of a Christian China 1836-1864

(Waco, TX: Baylor University, 1996), 6.

6

P. M. Yap, “The Mental Illness of Hung Hsiu-Ch'uan, Leader of the Taiping Rebellion,”

The Far Eastern Quarterly

13, no. 3 (1954): 289.

P. M. Yap, “The Mental Illness of Hung Hsiu-Ch'uan, Leader of the Taiping Rebellion,”

The Far Eastern Quarterly

13, no. 3 (1954): 289.

8

Ibid., 38-39.

Ibid., 38-39.

9

Quoted in Yap, 291.

Quoted in Yap, 291.

10

Ibid.

Ibid.

11

Vincent Y. C. Shih,

The Taiping Ideology: Its Sources, Interpretations, and Influences

(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972), 13.

Vincent Y. C. Shih,

The Taiping Ideology: Its Sources, Interpretations, and Influences

(Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1972), 13.

12

Yap, 292.

Yap, 292.

13

Philip A. Kuhn, “Origins of the Taiping Vision: Cross-Cultural Dimensions of a Chinese Rebellion,”

Comparative Studies in Society and History

19, no. 3 (1977): 352.

Philip A. Kuhn, “Origins of the Taiping Vision: Cross-Cultural Dimensions of a Chinese Rebellion,”

Comparative Studies in Society and History

19, no. 3 (1977): 352.

14

Yap, 294.

Yap, 294.

15

Yuan Chung Teng, “Reverend Issacher Jacox Roberts and the Taiping Rebellion,”

The Journal of Asian Studies

3, no., 1 (1963): 56.

Yuan Chung Teng, “Reverend Issacher Jacox Roberts and the Taiping Rebellion,”

The Journal of Asian Studies

3, no., 1 (1963): 56.

16

Franz Michael,

The Taiping Rebellion: History and Documents,

vol. 3 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1971), 1574.

Franz Michael,

The Taiping Rebellion: History and Documents,

vol. 3 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1971), 1574.

17

Spence, 107-108.

Spence, 107-108.

18

Michael, 1580-1581. Hakka women were much more liberated than other Chinese women of the time or women in the west.

Michael, 1580-1581. Hakka women were much more liberated than other Chinese women of the time or women in the west.

19

Shih, 402.

Shih, 402.

21

Quoted in Yap, 295. Yap concludes that Hong may have been suffering from schizophrenic paranoia.

Quoted in Yap, 295. Yap concludes that Hong may have been suffering from schizophrenic paranoia.

22

Teng, 64-66.

Teng, 64-66.

23

Translated in Michael, 933.

Translated in Michael, 933.

24

Ibid., 931.

Ibid., 931.

25

Several of these are translated in Michael, 1351-1542.

Several of these are translated in Michael, 1351-1542.

26

One of the tracts, “A Hero's Return to Truth,” details these promises, along with the reiteration of the divine nature of the Heavenly King Hong. See Michael, 799-832.

One of the tracts, “A Hero's Return to Truth,” details these promises, along with the reiteration of the divine nature of the Heavenly King Hong. See Michael, 799-832.

27

Beeching, 321.

Beeching, 321.

28

Ibid., 331.

Ibid., 331.

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

The Doomsealers

An old lady on Dwight way, Berkeley, has sold her property

for $3000 ($1500 below value), because of the predictions of

the Oakland doomsealers. She will leave for the mountains in

the course of a few days. Her neighbors are highly elated

because they have been greatly annoyed by her midnight

prayers and songs.

for $3000 ($1500 below value), because of the predictions of

the Oakland doomsealers. She will leave for the mountains in

the course of a few days. Her neighbors are highly elated

because they have been greatly annoyed by her midnight

prayers and songs.

â

Oakland Tribune

(March 12, 1890)

Oakland Tribune

(March 12, 1890)

Â

Â

Â

Â

D

uring the winter of 1889, a charismatic preacher arrived in Oakland, California, to conduct a tent revival meeting. Mrs. Maria B. Woodworth was already known as an evangelical preacher in the Midwest, coming from near Muncie, Indiana.

1

She was one of the forerunners of the Pentecostal movement. Although not affiliated with any particular church, her revivals were sponsored by Methodist, United Brethren, and Churches of God congregations in the areas where she preached.

2

uring the winter of 1889, a charismatic preacher arrived in Oakland, California, to conduct a tent revival meeting. Mrs. Maria B. Woodworth was already known as an evangelical preacher in the Midwest, coming from near Muncie, Indiana.

1

She was one of the forerunners of the Pentecostal movement. Although not affiliated with any particular church, her revivals were sponsored by Methodist, United Brethren, and Churches of God congregations in the areas where she preached.

2

She encouraged those who attended the meetings to open themselves up to divine wisdom. On January 25, 1890, one of the attendees was a twenty-nine-year-old Norwegian immigrant named George Erickson. Responding to Woodworth's exhortations, he fell into a trance during which he had a vision of a great earthquake and tidal wave destroying Oakland and San Francisco on April 14 of that year.

3

3

Shortly thereafter, others had the same vision, with a Mrs. Gifford, giving the exact time of the earthquake as 4:45 P.M. In the next few days, the prophecy was expanded to include the destruction of Chicago and Milwaukee.

4

4

As with the Millerites, the newspapers had a great time making fun of the Doomsealers. The

Oakland Tribune

was particularly eloquent: “The day of wrath, that dreadful day when the waters shall come up to thirty-sixth street and beyond has been officially fixed for April 14 prox. . . . For the followers of Mrs. Woodworth have said it and so it must come to pass.” The article concludes: “Notice of the flood will duly be sent out to all those who affiliate with the Woodworth converts, and Mr. Bennett will spread the tidings from his bicycle.”

5

According to Hayes, Bennett did indeed fulfill his task. He “mounted his bicycle and rode up and down the city streets and the country roads, crying aloud, “Flee! Flee! Flee! Flee to the mountains!”

6

Oakland Tribune

was particularly eloquent: “The day of wrath, that dreadful day when the waters shall come up to thirty-sixth street and beyond has been officially fixed for April 14 prox. . . . For the followers of Mrs. Woodworth have said it and so it must come to pass.” The article concludes: “Notice of the flood will duly be sent out to all those who affiliate with the Woodworth converts, and Mr. Bennett will spread the tidings from his bicycle.”

5

According to Hayes, Bennett did indeed fulfill his task. He “mounted his bicycle and rode up and down the city streets and the country roads, crying aloud, “Flee! Flee! Flee! Flee to the mountains!”

6

In early April, Maria Woodworth was supposed to have gone ahead to Santa Rosa, in Marin County, to prepare shelter for those who sought refuge from the coming cataclysm. The newspaper accounts are somewhat confusing, but she seems to have departed for the East, instead. She might have stayed until it was clear that the catastrophe wasn't about to happen, but that isn't certain.

Before the day of the predicted disaster, a number of believers did go to higher ground. They went up into the Berkeley Hills, perhaps in imitation of those who fled the opening of the sixth seal of the Apocalypse and “hid in caves and among the rock of the mountains” (Revelation 6:25). Papers all over the country had picked up the story.

The New York Times

insisted that sensible Americans were not fooled and that most of the believers were either “colored” or recent immigrants.

7

It's not clear where this information came from for the Oakland paper gave names of a number of local citizens who were leaving for the mountains, including a prominent doctor and his wife.

8

The New York Times

insisted that sensible Americans were not fooled and that most of the believers were either “colored” or recent immigrants.

7

It's not clear where this information came from for the Oakland paper gave names of a number of local citizens who were leaving for the mountains, including a prominent doctor and his wife.

8

The day passed without incident, and the Doomsealers started to return to their homes. An account of an interview with A. H. Wood, a member who did not flee, stated that “he knows of people who put faith in the prophecy whose names, if made public, would create surprise. He does not think that those who left will hasten back, but will drop in town quietly. The reasons given later by some of the Doomsealers for their flightâsuch as that they were leaving for their health, or business of other causesâwere fictitious, and they were really afraid for their lives.”

9

9

Other books

Catching Fireflies by Sherryl Woods

The Kill Zone by Ryan, Chris

The Laird by Blair, Sandy

The Green Glass Sea by Ellen Klages

Family In The Making (Matchmakeing Babies 2) by Jo Ann Brown

A Fall of Princes by Judith Tarr

Enlightenment by Maureen Freely

Cast In Dark Waters by Gorman, Ed, Piccirilli, Tom

Season of the Sun by Catherine Coulter

Payoff for the Banker by Frances and Richard Lockridge