The Real History of the End of the World (33 page)

Read The Real History of the End of the World Online

Authors: Sharan Newman

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

6.45Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

2

Paul B. Roscoe, “The Far Side of Harun: The Management of Melanesian Millenarian Movements,”

American Ethnologist

15, no. 3 (1988): 517. Most of the examples here are from Papua New Guinea. It seems to have been more overrun with anthropologists than other places.

Paul B. Roscoe, “The Far Side of Harun: The Management of Melanesian Millenarian Movements,”

American Ethnologist

15, no. 3 (1988): 517. Most of the examples here are from Papua New Guinea. It seems to have been more overrun with anthropologists than other places.

3

Actually, this happens in most human interactions; it's just more pronounced here.

Actually, this happens in most human interactions; it's just more pronounced here.

4

Jean Guiart, “Conversion to Christianity in the South Pacific,” in

Millennial Dreams in Action,

ed. Sylvia L. Thrupp (New York: Schocken, 1970), 122-123.

Jean Guiart, “Conversion to Christianity in the South Pacific,” in

Millennial Dreams in Action,

ed. Sylvia L. Thrupp (New York: Schocken, 1970), 122-123.

5

Ibid., 125-127.

Ibid., 125-127.

6

Roger Ivar Lohman, “The Afterlife of Asabano Corpses: Relationships with the Deceased in Papua New Guinea,”

Ethnology

44, no. 2 (2005): 202.

Roger Ivar Lohman, “The Afterlife of Asabano Corpses: Relationships with the Deceased in Papua New Guinea,”

Ethnology

44, no. 2 (2005): 202.

7

Justus M. van der Kroef, “The Messiah in Indonesia and Melanesia,”

The Scientific Monthly

25, no. 3 (1952): 163.

Justus M. van der Kroef, “The Messiah in Indonesia and Melanesia,”

The Scientific Monthly

25, no. 3 (1952): 163.

8

Stephen Leavitt, “The Apotheosis of White Men?: A reexamination of Beliefs about Europeans as Ancestral Spirits,”

Oceania

70, no. 4 (2000): 309.

Stephen Leavitt, “The Apotheosis of White Men?: A reexamination of Beliefs about Europeans as Ancestral Spirits,”

Oceania

70, no. 4 (2000): 309.

9

Ibid., 309.

Ibid., 309.

10

Joel Robbins,” Becoming Sinners: Christianity and Desire among the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea,”

Ethnology

, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Autumn, 1998), 302.

Joel Robbins,” Becoming Sinners: Christianity and Desire among the Urapmin of Papua New Guinea,”

Ethnology

, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Autumn, 1998), 302.

11

Richard Ewes, “Waiting for the Day: Globalisation and Apocalypticism in Central New Ireland, Papua New Guinea,”

Oceania

71 (2000): 351.

Richard Ewes, “Waiting for the Day: Globalisation and Apocalypticism in Central New Ireland, Papua New Guinea,”

Oceania

71 (2000): 351.

12

Justus M. van der Kroef, “Javanese Messianic Expectations: Their Origin and Cultural Context,”

Comparative Studies in Society and History

1, no. 4 (1959): 300.

Justus M. van der Kroef, “Javanese Messianic Expectations: Their Origin and Cultural Context,”

Comparative Studies in Society and History

1, no. 4 (1959): 300.

13

Ibid., 301.

Ibid., 301.

14

Ibid., 305.

Ibid., 305.

15

Michael Adas,

Prophets of Rebellion: Millenarian Protest Movements against the European Colonial Order

(Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 98.

Michael Adas,

Prophets of Rebellion: Millenarian Protest Movements against the European Colonial Order

(Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 98.

16

Ibid., 99.

Ibid., 99.

17

Martin Ramstedt,

Hinduism in Modern Indonesia: Between Local, National and Global Interests

(Florence, KY: Routledge-Curzon, 2003), 16-17.

Martin Ramstedt,

Hinduism in Modern Indonesia: Between Local, National and Global Interests

(Florence, KY: Routledge-Curzon, 2003), 16-17.

18

Kroef, “Javanese Messianic Expectations,” 311.

Kroef, “Javanese Messianic Expectations,” 311.

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

The Fifth World

Hopi Prophecy and 2012

Â

It is time for the end times here, that was prophesizedand through the dreams that were given to us also.

Through those dreams we are learning that we are

getting very close to the end times.

âGrandfather 2, radio interview with Art Bell (June 15, 1998)

Â

Â

Â

Â

A

mong the many examples put forward by those who think that the world will end in 2012, the Hopi Fifth World is often mentioned. Since the 1960s, the idea of the Fifth World has drawn the interest of many non-Hopi people, with the result that fragments of the stories have entered into the mix that makes up New Age beliefs.

mong the many examples put forward by those who think that the world will end in 2012, the Hopi Fifth World is often mentioned. Since the 1960s, the idea of the Fifth World has drawn the interest of many non-Hopi people, with the result that fragments of the stories have entered into the mix that makes up New Age beliefs.

A historian of religion who has studied the Hopi language and culture for many years compiled several versions of the Hopi Emergence story, which is essential to understanding the Last Day end of the world prophecy.

1

1

The main story of the Emergence explains that the Hopi are now living in the Fourth World. The first three that were given to them, one after another, became unlivable. Each time, people were neglecting the old ways and, particularly, being sexually promiscuous. The few people who still lived according to the Path sent a bird to find a hole in the sky so that they could climb a reed up to it and into a better world. They then made the journey to this world, the fourth, which was at that time untouched by evil. They thought they had been careful to kick the reed ladder away before the corrupt ones could climb up after them. However, soon after their arrival, the chief 's (

kikmongwi

) child became ill and died. Death should not have existed in the Fourth World, so the people realized that somehow a wicked person, a witch, had come up with them. They discovered the witch and were about to throw it back down to the Third World. But the witch convinced the chief to look back down the hole, where he saw that his child was alive and happy in the afterlife. So, the witch was allowed to stay. Nevertheless, this act allowed evil to enter the Fourth World.

2

kikmongwi

) child became ill and died. Death should not have existed in the Fourth World, so the people realized that somehow a wicked person, a witch, had come up with them. They discovered the witch and were about to throw it back down to the Third World. But the witch convinced the chief to look back down the hole, where he saw that his child was alive and happy in the afterlife. So, the witch was allowed to stay. Nevertheless, this act allowed evil to enter the Fourth World.

2

Because evil became part of the new world, death and corruption soon followed. Some believe that the signs say it is time to ascend to the Fifth World. This is based on moral and ecological observations. The belief that the tipping point has passed in our exploitation of the earth is one that resonates with many people. The feeling is that the old world must be destroyed and the few righteous need to be ready to move on.

The variations on this basic story are many. Hopi scholar Geertz found at least twelve, and Lomatuway'ma gives fragments of more.

3

In some, the reed grows to break into the Fourth World rather than finding a hole already there. In some the child is a girl, in others a boy. Likewise, the witch can be male or female. Sometimes the witch is a relative of the leader. The decision to allow the witch to remain is sometimes that of the chief; in others the entire community is responsible.

4

The story as a whole is much more complex, including the creation of the sun and moon, arrangements made with the gods and the ancestors, and the migrations of the Hopi. Again, each version is different. They were collected, mainly by Indo-Europeans, over the past 120 years from a variety of sources.

3

In some, the reed grows to break into the Fourth World rather than finding a hole already there. In some the child is a girl, in others a boy. Likewise, the witch can be male or female. Sometimes the witch is a relative of the leader. The decision to allow the witch to remain is sometimes that of the chief; in others the entire community is responsible.

4

The story as a whole is much more complex, including the creation of the sun and moon, arrangements made with the gods and the ancestors, and the migrations of the Hopi. Again, each version is different. They were collected, mainly by Indo-Europeans, over the past 120 years from a variety of sources.

Â

Â

THE apocalyptic scenario of the Hopi people has become, in many ways, an explosive subject. It entails rights of societal privacy, appropriation of cultures, and debates within the Hopi community. It also has become part of another tradition altogether, one that has nothing to do with the Hopi people or their beliefs.

As I researched this subject, I soon realized that, with the exception of a few serious scholars, most people have come across the Hopi prophecies through the writing of Euro-Americans. Some of these non-Hopi authors have heard English versions from Hopi informants. Others get the story secondhand or thirdhand through books and magazine articles. Many more know of the prophecies through television or the Internet.

5

5

Therefore, this section deals more with what use has been made of these prophecies and what need they fill in non-Hopi people, than the actual story. The many variations in the tale indicate that there isn't one original prophecy. The differences are not as important as the collective spiritual and emotional impact. I have concluded that, if one doesn't speak Hopi and hasn't grown up in a traditional Hopi environment, there isn't much chance of understanding the prophecies in the correct context.

Due to the lack of oil, gold, and fertile soil, the Hopi lands of the American Southwest were not overrun by settlers in the nineteenth century. This allowed the Hopi and other nearby tribes, particularly the Navaho, with whom the Hopi have ongoing boundary disputes, to preserve their language and way of life much longer than Native Americans living in other areas. For many years into the twentieth century, the Hopi were mainly of interest only to students of languages and ethnology.

6

6

The Hopi continue to live on their ancestral land near the Four Corners, in Arizona, on three mesas. Each of the mesa communities has its own distinct characteristics. The Oraibi village on the third mesa was, until recently, the largest and has been the focal point for many outsiders who follow the prophecy of the coming end of this world that has been created through a blend of traditional and New Age beliefs. The village of Hoteville, Arizona, also on the third mesa, is a base for those Hopi who are offended by the appropriation of their beliefs by outsiders.

7

Hoteville was founded after a split in the Oraibi community. There is no one universal Hopi opinion on the coming of the Fifth World and the interest in it by non-Hopi.

7

Hoteville was founded after a split in the Oraibi community. There is no one universal Hopi opinion on the coming of the Fifth World and the interest in it by non-Hopi.

The first difficulty in understanding the Hopi prophecies is one of language. Hopi is an Uto-Aztecan language, nothing like Indo-European-based ones. One can't make a direct translation from Hopi to English, only an approximation. This is true of translations from any language but even more so with one so different from that of the translators.

In Hopi, an exact, literal translation makes little sense in English, needing to be translated once again into colloquial speech. For example, in a study of Hopi lullabies, the authors freely admit that even with something as universal as a mother's song to her children, the “exact duplication of the poems in English was impossible . . . Often the implicit meanings accessible to Hopis appear cryptic in English.”

8

The implicit meanings of speech are determined by the culture one lives in. In any language even native speakers can become confused if a story refers to experiences that the listener doesn't share.

8

The implicit meanings of speech are determined by the culture one lives in. In any language even native speakers can become confused if a story refers to experiences that the listener doesn't share.

Therefore, any prophecy that is read in a language other than Hopi has already been interpreted by the translator, even if that person is a native Hopi speaker.

The other stumbling block is the idea of what a prophecy is. Western tradition has it as something foreseen, sometimes under divine inspiration, by one person. A prophecy is set in stone. It doesn't appear that this matches the Hopi concept. The same basic story may be told differently according to the clan of the teller, the person hearing the story, or the time in which it is told. That does not make any of these invalid.

The mistake that early scholars made was to insist that there must be one Ur-myth, a place where all the stories began. And they believed that, if they could find it, they would find the truth. This belief was common among early biblical scholars and collectors of European folk tales as well. Recently, researchers have come to the conclusion that stories in the oral tradition are all valid in their own way and that it is more important to look at them individually to discover what they say about the culture of the teller, rather than to uncover the first telling.

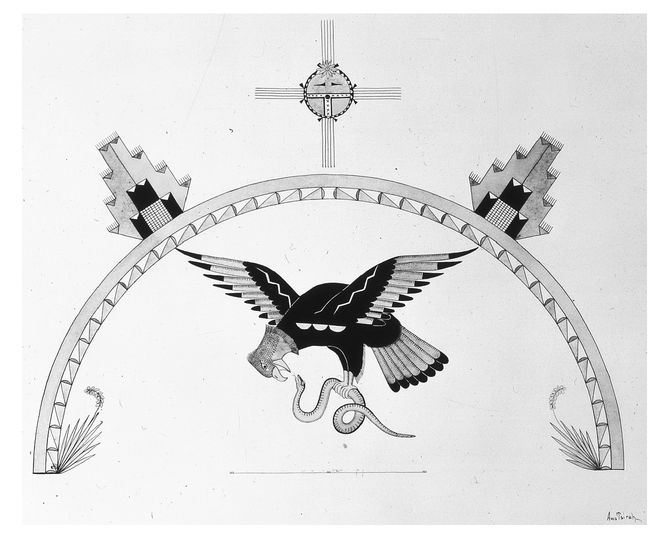

Awa, Tsireh (1895-1985) Hopi pattern: Eagle with Snake, c.1925-1930. Watercolor and ink on paper, 11 1/4 x 14 1/4. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, U.S.A.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC / Art Resource, NY

I think that this is the attitude we must take with the end time prophecy of the Hopi. There are Hopi prophecies of the end of the Fourth World. They were not made up by outsiders. Some may be thousands of years old. Many of them are recent. That doesn't make the latter any less valid; they are modern wisdom rather than ancient.

The Hopi end of the Fourth World prophecy was first popularized by Frank Waters (1902-1995) in his 1963 work,

The Book of the Hopi

. Waters was a life-long westerner who had a great respect for and interest in Native American society. He had previously written several western novels with strong, sympathetic Indian characters. He was part Indian on his father's side, although not Hopi. He was part of the Taos group of writers and artists in the 1940s, where he was influenced by non-Western spirituality including Buddhist and Hindu thought.

9

While visiting Hopi villages, Waters understood their belief system as a rejection of Western materialism and greed as well as being in line with Eastern spirituality. His work reflects his desire to portray the Hopi beliefs as unified with other non-Western religions in their mutual desire for peaceful co-existence with the planet.

10

The Book of the Hopi

. Waters was a life-long westerner who had a great respect for and interest in Native American society. He had previously written several western novels with strong, sympathetic Indian characters. He was part Indian on his father's side, although not Hopi. He was part of the Taos group of writers and artists in the 1940s, where he was influenced by non-Western spirituality including Buddhist and Hindu thought.

9

While visiting Hopi villages, Waters understood their belief system as a rejection of Western materialism and greed as well as being in line with Eastern spirituality. His work reflects his desire to portray the Hopi beliefs as unified with other non-Western religions in their mutual desire for peaceful co-existence with the planet.

10

When he introduced the idea of the Fifth World to the general reader, Waters's timing was perfect. The Cuban missile crisis of 1962 had convinced millions of people that we were on the brink of nuclear war and total annihilation.

11

Waters announced that the Hopi had foreseen that the world would be destroyed in a nuclear holocaust, with only the Hopi and other disenfranchised people surviving to mount to the Fifth World.

12

11

Waters announced that the Hopi had foreseen that the world would be destroyed in a nuclear holocaust, with only the Hopi and other disenfranchised people surviving to mount to the Fifth World.

12

There are prophecies among the Hopi that the Fourth World is ending. “It is firmly believed that Hopiland will become the regenerated Center of the World after the catastrophes,” Waters insisted.

13

But what are these prophecies? There seem to be as many versions among the Hopi of the end as there are Emergence stories. The belief that only those who follow the Hopi traditions and rituals will be saved seems to be the only constant.

13

But what are these prophecies? There seem to be as many versions among the Hopi of the end as there are Emergence stories. The belief that only those who follow the Hopi traditions and rituals will be saved seems to be the only constant.

While the Hopi Third World was abandoned because of immorality, the Fourth World is in danger because of nuclear war, pollution, and lack of respect for the earth. These fall in well with the convictions of many outsiders. Several of the reported prophecies also state that the god Maasaw guided the Hopi into the Fourth World and left them to their own devices. He promised he would return at the end of the fourth cycle. Part of the prophecy seems to be that, before he left, Maasaw gave sacred prophetic tablets to two brothers. These stone tablets foretold the signs indicating that the Fourth World was about to end. One brother stayed in the west on the Hopi land. The other, White Brother, went east with a piece of the tablets. It is said that White Brother will return just before the end with the tablet fragment. When the pieces are joined, the signs will be made clear and the exodus to the Fifth World will begin.

14

14

Other books

Joe Victim: A Thriller by Paul Cleave

Juego mortal by David Walton

Marrow by Tarryn Fisher

Brownies by Eileen Wilks

Straw Men by Martin J. Smith

You Can't Get Lost in Cape Town by Zoë Wicomb

This Blackened Night by L.K. Below

Sweet Damage by Rebecca James

Compete by Norilana Books

Jane Austen by Andrew Norman