The Real History of the End of the World (22 page)

Read The Real History of the End of the World Online

Authors: Sharan Newman

BOOK: The Real History of the End of the World

10.69Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Many of the Fifth Monarchists were in the army and had fought first for the king and then against him. One of the military leaders who played an important role in the Fifth Monarchy and in the government during the Interregnum (the eleven years between the death of Charles I and the return of Charles II) was Thomas Harrison. Harrison was both a major general in the New Model Army, under Oliver Cromwell, and a member of the Barebones Parliament.

Harrison (1606-1660) was the son of a Newcastle-under-Lyme butcher who had risen to be mayor of the city. He worked as a clerk in London until the start of the Civil War, when he enlisted on the side of Parliament. He must have been a good soldier for, by 1645, he was a colonel.

5

5

He was also a staunch believer in the coming of the millennium. He argued for the execution of King Charles and was one of those who signed his death warrant. He must have been a charismatic man; portraits show him looking very little like a conventional Puritan. His hair was long and curled, and he wore lace collars and fine suits. This did not prevent him from fighting in Parliament against immorality and the system of tithing citizens to support the clergy.

6

He seems to have been rigid and uncompromising in his faith, certain that he was one of the saints who would prepare the kingdom, with a rather touching naïveté about the possibility of success. When the Barebones Parliament was dismissed and Oliver Cromwell became lord protector, Harrison felt betrayed. That was the role of Jesus. Suddenly his hero had become another “little horn.” However, Harrison did not mount a rebellion against Cromwell. Ordered to retire to his home in Staffordshire in 1654, he went, vowing to live peaceably.

7

6

He seems to have been rigid and uncompromising in his faith, certain that he was one of the saints who would prepare the kingdom, with a rather touching naïveté about the possibility of success. When the Barebones Parliament was dismissed and Oliver Cromwell became lord protector, Harrison felt betrayed. That was the role of Jesus. Suddenly his hero had become another “little horn.” However, Harrison did not mount a rebellion against Cromwell. Ordered to retire to his home in Staffordshire in 1654, he went, vowing to live peaceably.

7

He seems to have done so, being held in not very close captivity until the Restoration. Charles II issued a general amnesty for many of the Puritan leaders but Harrison was not included. His name on the death warrant of the king's father condemned him. Harrison was tried and convicted. He was executed on October 13, 1660. The diarist and gadabout Samuel Pepys went to see the show and wrote, “I went out to Charing Cross, to see Major-General Harrison hanged, drawn and quartered; which was done there, he looking as cheerful as any man could do in that condition.”

8

8

In contrast to the elegant Harrison was Thomas Venner. Venner was a cooper who emigrated to New England sometime before 1638. He lived first in Salem, Massachusetts, and then Boston before returning to England in 1651.

9

He got a job at the Tower of London and became involved in the Fifth Monarchy movement. In 1655, he was dismissed from the Tower, allegedly for plotting to blow it up.

10

In 1657, he attempted to start a popular rebellion. In his notebook, he wrote, “Our present apprehension is, that having a convenient place providence, we fall uppon a troupe of Horse & execute their officers & all others of the guards or private souldiers that shall oppose us, and take their horses to horse our men, because the Lord hath need.”

11

Venner's insurrection was supposed to take place on April 7, 1657, but the plotters were betrayed and captured. Venner spent the next two years in the Tower, this time as a prisoner.

12

9

He got a job at the Tower of London and became involved in the Fifth Monarchy movement. In 1655, he was dismissed from the Tower, allegedly for plotting to blow it up.

10

In 1657, he attempted to start a popular rebellion. In his notebook, he wrote, “Our present apprehension is, that having a convenient place providence, we fall uppon a troupe of Horse & execute their officers & all others of the guards or private souldiers that shall oppose us, and take their horses to horse our men, because the Lord hath need.”

11

Venner's insurrection was supposed to take place on April 7, 1657, but the plotters were betrayed and captured. Venner spent the next two years in the Tower, this time as a prisoner.

12

It's a tribute to the patience of Oliver Cromwell that he did not execute Venner. Cromwell's son, Richard, let him go free after Oliver's death. The determined Venner immediately started planning another uprising in which he encouraged his followers to “take up arms for King Jesus against the Powers of the Earth.”

13

However, this rebellion did not get started until 1661, a year after the return of King Charles II. Charles was not convinced that this was the time for a new kingdom. Venner was executed January 19, 1661.

13

However, this rebellion did not get started until 1661, a year after the return of King Charles II. Charles was not convinced that this was the time for a new kingdom. Venner was executed January 19, 1661.

It may have been noted that the Fifth Monarchy was made up totally of men. That's not entirely true. Women had a role in the movement, not as leaders or soldiers, but as prophets.

Two women were particularly well known for their visions, Anna Trapnell and Mary Cary. Little is known about Cary's life before she began publishing her visions in 1647. In 1653, she published

The Little Horn's Doom and Downfall

, a justification of the Fifth Monarchy tenets.

14

Although it was published four years after the king was executed, Cary insisted that she wrote the book before the events that are predicted therein.

15

She justified the establishment of the kingdom of God in England rather than Jerusalem because there were so many more saints already there. Also, along with many Fifth Monarchy adherents as well as other millenarians, Cary argued for the readmission of the Jews to England. They had been expelled in 1290, and many were certain that they must be allowed to return in order to be converted so that Jesus would return.

16

The Little Horn's Doom and Downfall

, a justification of the Fifth Monarchy tenets.

14

Although it was published four years after the king was executed, Cary insisted that she wrote the book before the events that are predicted therein.

15

She justified the establishment of the kingdom of God in England rather than Jerusalem because there were so many more saints already there. Also, along with many Fifth Monarchy adherents as well as other millenarians, Cary argued for the readmission of the Jews to England. They had been expelled in 1290, and many were certain that they must be allowed to return in order to be converted so that Jesus would return.

16

Anna Trapnel, the daughter of a shipwright from Stepney, had her first visions in 1643. However, she didn't make them public until 1654. She did not write down her own prophecies, although she was literate, but delivered them in a trance for others to write, calling herself an instrument of God. The spirit speaking through her spoke both poetry and prose, all in support of the Fifth Monarchy opinions on the Book of Daniel and the way that Oliver Cromwell had fallen into tyranny.

17

Unmarried, she traveled alone. She was arrested once in Cornwall and tried, mainly for being a troublemaker, and spent time in prison. Her next pamphlet,

A Report and Plea,

tells the story of her treatment by the court and the disapproving populace.

18

17

Unmarried, she traveled alone. She was arrested once in Cornwall and tried, mainly for being a troublemaker, and spent time in prison. Her next pamphlet,

A Report and Plea,

tells the story of her treatment by the court and the disapproving populace.

18

The visions of these women, accepted by many as divinely inspired, helped strengthen the resolve of the Fifth Monarchy supporters. However, by the late 1650s the English people in general realized that rule by saints was not working. For one thing, although a person could think life was hard because the king was a tyrant; it was less comfortable to say God was one, especially within the hearing of his divinely appointed lieutenants.

Charles II did not have to reconquer England, although there were military uprisings in his support. The Long Parliament had been reinstated, including the moderates who had been forced out in 1648. They voted overwhelmingly to invite the king to come back. Some even praised him as the Fifth Monarch.

19

He landed at Dover in 1660 and began the gloriously decadent Restoration.

19

He landed at Dover in 1660 and began the gloriously decadent Restoration.

The arrival of King Charles with no opposition from King Jesus was a terrible blow to the remaining Fifth Monarchists. Thomas Venner's failed insurrection was the last major attempt at establishing a kingdom of saints. The Fifth Monarchist believers eventually blended in with other dissenting Protestant groups. One small band evidently decided that England wasn't the place to await the Second Coming and set up a community in the German Palatinate, where they were rumored to be living according to Jewish law.

20

20

The year 1666 raised the hopes of many and the horrors of the plague and the Great Fire of London made many in England feel that Armageddon was near.

While most who take part in a rebellion think that God must be on their side, few expect him to bodily lead the army. The Fifth Monarchists did. This rigid certainty as to the divine justice of their cause made them unable to compromise. It also made some of them, like Harrison and Venner, prefer martyrdom. While the majority of the English did not support them, many admired the constancy of their faith and this was underscored when, in 1688, the Stuart kings were sent packing in favor of the strongly Protestant daughter of James II and her husband, William of Orange.

1

Champlin Burrage, “The Fifth Monarchy Insurrection,”

English Historical Review

25, no. 100 (1910): 740.

Champlin Burrage, “The Fifth Monarchy Insurrection,”

English Historical Review

25, no. 100 (1910): 740.

2

The preceding mini-history is my own interpretation of events, seriously condensed. It should not be used if you are studying for an exam on the Civil War.

The preceding mini-history is my own interpretation of events, seriously condensed. It should not be used if you are studying for an exam on the Civil War.

3

New Revised Standard Bible.

New Revised Standard Bible.

4

Bernard Capp,

The Fifth Monarchy Men: A Study in Seventeenth Century Millenarianism,

(London: Faber & Faber, 2008): 64.

Bernard Capp,

The Fifth Monarchy Men: A Study in Seventeenth Century Millenarianism,

(London: Faber & Faber, 2008): 64.

6

Leo F. Solt, “The Fifth Monarchy Men: Politics and the Millennium,”

Church History

30, no. 3 (1961): 314.

Leo F. Solt, “The Fifth Monarchy Men: Politics and the Millennium,”

Church History

30, no. 3 (1961): 314.

7

Capp, p. 100.

Capp, p. 100.

8

Quoted in Rogers, 107.

Quoted in Rogers, 107.

9

Capp, 267.

Capp, 267.

10

Burrage, 723.

Burrage, 723.

11

Quoted in ibid., 730.

Quoted in ibid., 730.

12

Ibid., 739.

Ibid., 739.

13

Ibid. 739.

Ibid. 739.

14

David Loewenstein, “Scriptural Exegesis, Female Prophecy and Radical Politics in Mary Cary,”

Studies in English Literature 1500-1900

46, no. 1 (2006): 134.

David Loewenstein, “Scriptural Exegesis, Female Prophecy and Radical Politics in Mary Cary,”

Studies in English Literature 1500-1900

46, no. 1 (2006): 134.

15

Rachel Warburton, “Future Perfect?: Elect Nationhood and the Grammar of Desire in Mary Cary's Millennial Visions,”

Utopian Studies

18, no. 2 (2007): 122.

Rachel Warburton, “Future Perfect?: Elect Nationhood and the Grammar of Desire in Mary Cary's Millennial Visions,”

Utopian Studies

18, no. 2 (2007): 122.

16

Ibid., 138. See also the section in this book on Jews and the Millennium.

Ibid., 138. See also the section in this book on Jews and the Millennium.

17

Champlin Burrage, “Anna Trapnel 's Prophecies,”

English Historical Review

26, no. 103 (1911): 5626-5635.

Champlin Burrage, “Anna Trapnel 's Prophecies,”

English Historical Review

26, no. 103 (1911): 5626-5635.

18

Susannah B. Mintz, “The Spectacular Self of âAnna Trapnel's Report and Plea,' ”

Pacific Coast Philology

35, no. 1 (2000): 1-16. The use women made of visions and prophecy in a patriarchal society is fascinating but, I am sad to say, can't be explored further in this book.

Susannah B. Mintz, “The Spectacular Self of âAnna Trapnel's Report and Plea,' ”

Pacific Coast Philology

35, no. 1 (2000): 1-16. The use women made of visions and prophecy in a patriarchal society is fascinating but, I am sad to say, can't be explored further in this book.

19

Capp, 194.

Capp, 194.

20

Ibid., 202.

Ibid., 202.

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

The Founders of Modern Science

He has studied the prophetic parts of

Scripture till he has bewildered himself.

Scripture till he has bewildered himself.

â

Gentleman's Magazine

(1795), 55

Gentleman's Magazine

(1795), 55

Â

Â

Â

Â

I

t is popular to think of the “long seventeenth century” as a time of enlightenment, when old superstitions were thrown out and rationale enquiry was established. The basic principles of chemistry, biology, and physics were established. It was an age of reason in which apocalyptic and millennial speculations were only for the uneducated.

t is popular to think of the “long seventeenth century” as a time of enlightenment, when old superstitions were thrown out and rationale enquiry was established. The basic principles of chemistry, biology, and physics were established. It was an age of reason in which apocalyptic and millennial speculations were only for the uneducated.

Well, that's not

exactly

the case.

JOHN NAPIERexactly

the case.

John Napier (1550-1617), eighth laird of Merchiston in Scotland, is well known as the inventor of logarithms. He is also credited with being the first to design a prototype computer. “These were wooden or bone prisms each lateral face of which was divided and marked by cross lines into small squares . . . he also mentions that there is a way of mounting metal plates in a box and multiplying and dividing by means of this mechanism.”

1

He also amused himself designing engines of war, including a sort of armored tank and a submarine.

2

1

He also amused himself designing engines of war, including a sort of armored tank and a submarine.

2

But this was only a part of his life. Napier was much involved in Scottish politics, particularly involving King James VI of Scotland, shortly to become James I of England. In 1593 Napier wrote a commentary on Revelation,

A Plaine Discovery of the Whole Revelation of Saint John.

He was much more famous for this book than he was for his mathematical genius. It went through twenty-one editions by 1700.

3

Dedicated to King James, the book is laid out with scientific precision. The first part consists of thirty-six propositions, followed by their proofs. The second half is his verse-by-verse explanation of the meaning of each sign described by John of Patmos.

4

It is not surprising that this Protestant Scot names the pope as Antichrist. It is surprising that this eminent mathematician had a problem making his math work in predicting the end. He figured that the last age of the world would be from 1541 to 1786. But he also believed that Christ would return sometime from 1698 to 1700. He finally explained that if the Elect were too impatient for the end that it would come ahead of schedule, “but I meane, that if the world wer to indure, the seventh age should continew until the yeare of Christ 1786.”

5

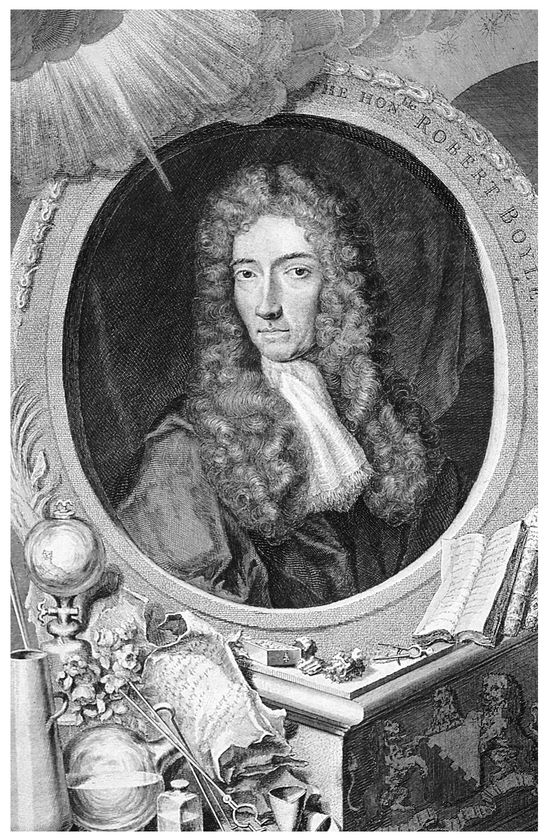

ROBERT BOYLEA Plaine Discovery of the Whole Revelation of Saint John.

He was much more famous for this book than he was for his mathematical genius. It went through twenty-one editions by 1700.

3

Dedicated to King James, the book is laid out with scientific precision. The first part consists of thirty-six propositions, followed by their proofs. The second half is his verse-by-verse explanation of the meaning of each sign described by John of Patmos.

4

It is not surprising that this Protestant Scot names the pope as Antichrist. It is surprising that this eminent mathematician had a problem making his math work in predicting the end. He figured that the last age of the world would be from 1541 to 1786. But he also believed that Christ would return sometime from 1698 to 1700. He finally explained that if the Elect were too impatient for the end that it would come ahead of schedule, “but I meane, that if the world wer to indure, the seventh age should continew until the yeare of Christ 1786.”

5

The aristocrat Robert Boyle (1627-1691) was the fourteenth child of the first earl of Cork and not in the slightest danger of inheriting any responsibility. He had a private tutor and, with his elder brother, spent five years touring Europe in his early teens. He was fascinated by science and had money and time in which to indulge his interests. Although born in Ireland, he spent most of his life in England.

6

Boyle is best known for his work with vacuum pumps and for Boyle's Law, which states that for a given mass, at a constant temperature, the pressure times the volume is a constant. He also was interested in isolating elements, using colormetric analysis to find iron in the water at Tunbridge Wells.

7

Finally, he was a mentor and inspiration to many younger scientists, including Isaac Newton.

6

Boyle is best known for his work with vacuum pumps and for Boyle's Law, which states that for a given mass, at a constant temperature, the pressure times the volume is a constant. He also was interested in isolating elements, using colormetric analysis to find iron in the water at Tunbridge Wells.

7

Finally, he was a mentor and inspiration to many younger scientists, including Isaac Newton.

Other books

Chew Bee or Not Chew Bee by Martin Chatterton

Collected Poems by Jack Gilbert

How to Date a Werewolf by Rose Pressey

The Same Woman by Thea Lim

The Dark's Mistress (The Saint-Pierres) by Hauf, Michele

The Fat Girl by Marilyn Sachs

The Hound of Rowan by Henry H. Neff

Stud for Hire by Sabrina York

Scandalous by Karen Robards

Sea of Glass (Valancourt 20th Century Classics) by Dennis Parry