The Plantagenets (81 page)

Authors: Dan Jones

Edward III wearing the blue robes of the Order of the Garter. This band of brothers bound England’s aristocrats together in the cause of war under a code of knightly chivalry, and reduced the political pressure exerted on Edward by the outrageous cost of his campaigns in France.

Edward III in Garter robes from William Bruges’s Garter Book,

c

.1440–50. (

© The British Library Board, Stowe 594, f.7v

)

Henry of Grosmont, duke of Lancaster, was Edward III’s greatest friend and – along with the Black Prince – the king’s most trusted general. Here, like Edward, he wears his Garter robes.

Henry of Grosmont from William Bruges’s Garter Book,

c

.1440–50. (

© The British Library Board, Stowe 594 f.8

)

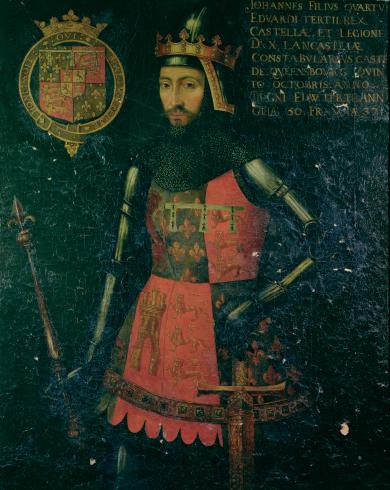

Edward III’s third surviving son, John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster, loomed large in the reign of his nephew Richard II. A divisive character in his life, his death in February 1399 prompted his son Henry Bolingbroke’s invasion of England and the final fall of the Plantagenet Crown.

John of Gaunt, portrait attributed to Lucas Cornelisz. (

Private Collection/The Bridgeman Art Library

)

At the time of his usurpation, Henry IV was likened by his staunch supporter Archbishop Arundel to Judas Maccabaeus, the popular biblical hero who had led God’s chosen people in rebellion against their oppressors, driven the iniquitous out of Jerusalem and repurified the Temple. It was a pointed analogy: like Henry, Maccabaeus had risen up to lead his people thanks to a blend of personal valour and military genius. He was a king who had earned his status by his righteousness, rather than by birth alone.

The beginning of Henry’s reign brought with it an intense propaganda drive, intended to emphasize the new king’s sanctity as well as his pragmatic suitability for office. Not only was he crowned on St Edward’s Day 1399; Henry was also anointed at his coronation with the vial of holy oil that had supposedly been given to Archbishop Thomas Becket by the Virgin Mary and which had subsequently come into the possession of the new king’s grandfather – Edward III’s great war captain, Henry Grosmont. At the feast that celebrated Henry’s coronation there was a pointed edge to the arrival in Westminster Hall of a knight, Sir Thomas Dymock, who claimed to be the king’s champion and announced to the assembled guests that if anyone disputed Henry’s right to be king of England, then ‘he was ready to prove the contrary with his body, then and there’. No one rose to challenge.

If Henry’s approval as the new king of England seemed indisputable, then Richard of Bordeaux’s death, four months after his deposition, was inevitable. Adam of Usk marvelled at the speed with which the old king had fallen, ‘cast down by the wheel of fortune, to fall

miserably in the hands of Duke Henry, amid the silent curses of your people’, and noted that had the king been ‘guided in your affairs by God and by the support of your people, then you would indeed have been deserving of praise’. Indeed, to judge by the ease and speed with which Henry Bolingbroke took the throne, there was as little general mourning for Richard as there had been for Edward II.

Nevertheless, like Edward II, Richard alive presented a focus for plotting by the fallen favourites of the old regime. In December 1399 a plot was hatched by a group of former Ricardians led by the earls of Rutland, Huntingdon, Kent and Salisbury. They planned to storm Windsor castle on the feast of Epiphany, 6 January 1400 – Richard’s forty-third birthday – disrupting the Twelfth Night celebrations, kidnapping the new king and his son, Prince Harry (who had been created prince of Wales, duke of Aquitaine, Lancaster and Cornwall and earl of Chester), and subsequently setting the old king at his liberty. However, fortune had long deserted Richard and his partisans: the plot was betrayed and easily disrupted. Neither Henry nor the prince was captured, and the rebels scattered across England, attempting unsuccessfully to raise popular rebellion as they went. The earls of Kent and Salisbury were beheaded by angry townsmen in Cirencester, the earl of Huntingdon was beheaded at sunset at Pleshey (on exactly the spot where the earl of Gloucester had been arrested by Richard in 1397), and Sir Thomas Despenser, another conspirator, was killed by the commons at Bristol. Far from a popular rising in favour of the old king, there was spontaneous and widespread rage at the efforts of his former allies to disrupt the English polity once again.

The failure of the Epiphany plot prompted Richard’s final demise. According to Thomas Walsingham, when the former king, serving his sentence of life imprisonment at Pontefract, ‘heard of these unhappy events, his mind became disturbed and he killed himself by voluntary fasting, so the rumour went’. The more sympathetic author of the

Traison et Mort

suggested foul play, claiming that the king was killed by one ‘Sir Piers Exton’, who staved in the king’s head with an axe. It is most likely that the truth lies somewhere between the extremes, and that Richard was deliberately starved on the orders of the new

Lancastrian regime, who could no more tolerate his presence in the realm than Roger Mortimer had been able to suffer that of Edward II in 1327. Adam of Usk laid the blame for Richard’s death by starvation on one ‘Sir N. Swynford’ (most likely Sir Thomas Swynford, a knight of Henry’s chamber).

Certainly, once Richard was dead – probably on St Valentine’s Day 1400 and certainly by 17 February – Henry IV was at pains to show his cousin’s corpse to the country. Richard’s emaciated body was transported from Pontefract to London with the face visible to all. The body lay in St Paul’s Cathedral for two days, before it was transported for burial at King’s Langley in Hertfordshire.

Richard’s deposition and Henry’s accession was viewed with some bewilderment by contemporaries. The metaphor of the wheel of fortune used by Adam of Usk seemed particularly apt. When the old king had cast Bolingbroke out into the wilderness and enjoyed the heyday of his tyranny, he had seemed to be the mightiest of all his line. Yet within months his entire reign had collapsed and he was dead. God’s providence was indeed a wonderful thing. But Richard’s fall was not entirely a matter of divine caprice. It was widely recognized that he had brought his misfortune upon himself by his atrocious behaviour, his violent misrule and his choice of poor company and counsel. He had neglected his realm in favour of enriching himself, and he had repeatedly treated his coronation oath, Magna Carta and the dignity of parliament with contempt. He had made it easy for Henry, his nearest heir in the male line, to take his Crown from him by appealing to the oldest principle of Plantagenet kingship, the principle that had been at the core of every moment of political and constitutional crisis since 1215: that the king should govern within his own law and with the advice of the worthiest men in his kingdom.

Despite the best efforts of the new regime to legitimize itself and argue the case for removing the old king, the Crown never fully recovered from the trauma of Richard’s deposition. Unlike Edward II, Richard had not been replaced by his undisputed heir, but by a nobleman who claimed sufficient royal blood to seize the throne, and did so to some degree unilaterally. Henry may have been the closest heir

to his cousin by the male line, but Edmund Mortimer, the great-grandson of Lionel of Antwerp via his daughter Philippa, countess of Ulster, had arguably a better claim in blood. Henry IV was not Edward III. A Rubicon had been crossed. The wars that erupted from the middle of the fifteenth century, known now as the Wars of the Roses, began as political wars but – thanks to the unanswered questions raised by Henry IV’s usurpation – they swiftly became wars of Plantagenet succession, which were only settled by the accession of a king, Henry VII, who was barely a Plantagenet at all. (Indeed, after Henry VII had legitimized his usurpation of the throne with a wealth of pageantry attempting to demonstrate his descent from Edward III, he and, later, his son Henry VIII set about murdering and destroying every surviving member of the English aristocracy with a trace of Plantagenet blood.) Richard’s deposition had marked the beginning of this baleful end.

In some ways, then, Henry IV’s accession threw the England monarchy back to a near-forgotten age. Not since Henry II had displaced Stephen’s son Eustace as heir to the English Crown in the 1150s had the royal succession so obviously combined blood-right with the principles of election and the blunt political reality of a power-grab. No royal dynasty would ever again hand down the Crown with such security and ease for so many generations as the Plantagenets did between 1189 and 1377.

Of course, Richard’s deposition did not turn the clock back to Norman times. The Plantagenet family’s legacy to England was profound, for by 1400 the realm had changed unrecognizably from the Anglo-Norman realm that had existed during the mid-twelfth century.

The office of kingship was utterly transformed. By 1400 the king was not just the most powerful man in the land, with the prerogatives of legal judgement, feudal tribute and warfare on behalf of the realm. Now he was an officeholder whose awesome rights were matched by awesome responsibilities in a complex, constitutional, contract with the various estates of the realm. Whereas the Norman kings (and the Saxon kings before them) had occasionally granted their subjects

limited and extremely vague charters of liberties, and governed in accordance with custom, the Plantagenet years had seen the growth of a highly refined political philosophy that defined the king’s duties to his realm and the realm’s to the king, and a huge body of common law and statute that governed the land. The king was still the source of universal authority in the realm, but his power underpinned a sophisticated system of justice and lawgiving.

Under these changed terms of rule, the king’s actions and his personal will still mattered immensely. The personalities of individual kings had profoundly shaped their reigns and their worlds, as had the personalities of their immediate relations – wives, brothers, children and cousins. In that sense, politics remained fundamentally unpredictable and unstable. Yet the Crown was also now distinct from the king, and the machinery and philosophy of royal rule more separate from the person of the king than at any time before. Each successive Plantagenet king had been more tempered by the last by a system of institutions that drew a broad political community into government. Parliaments – including elected representatives of county society, rather than just the great barons and ecclesiastical magnates – reserved the right to grant taxes, and expected that their grievances should be heard and remedied in exchange for the privilege. Government could be scrutinized, inadequate ministers impeached and, ultimately, a king might be removed from office: even the most capable and successful of the later Plantagenet kings, Edward I and Edward III, had experienced uncomfortable moments of crisis in 1297, 1341 and 1376. Parliaments, as well as the battlefield, would become the forums for much of the political upheaval that followed during the fifteenth century.