The Plantagenets (80 page)

Authors: Dan Jones

Images like this of Richard the Lionheart

left

jousting with Saladin during the Third Crusade became a widely repeated symbol of Plantagenet family lore and English history during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. In fact, despite their mutual admiration, the two great warriors never met in person.

Richard and Saladin from ‘The Luttrel Psalter’, 1320–40. (

The Art Archive/British Museum

)

A French chronicle depicts the fall of Acre in 1191, one of Richard I’s most significant victories during the Third Crusade. The city was in Christian hands for precisely 100 years, and Edward I visited in the 1270s.

The Capture of Acre from ‘Chroniques de France ou de St Denis’,

c

.1325–50. (

Scala, Florence/Heritage Images

)

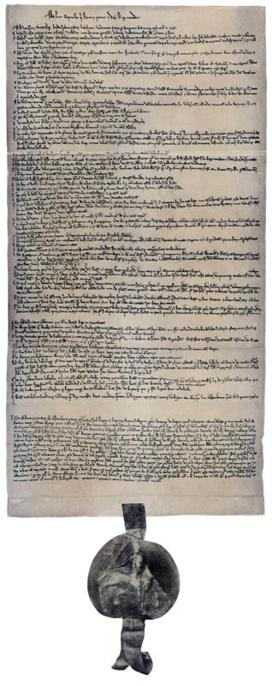

Magna Carta was a peace treaty which failed to end civil war between King John and his barons. Nevertheless, the principles of justice and government it evoked would be central to every political crisis of the Plantagenet age.

Lower section of Magna Carta. (

The Print Collector/HIP/Topfoto

)

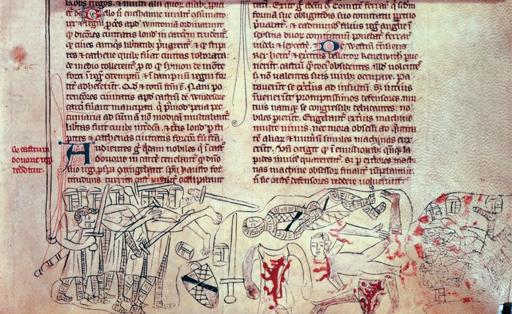

Simon de Montfort is hacked to pieces at the battle of Evesham in 1265. De Montfort’s prickly opposition to Henry III has given him the reputation as the father of English parliamentary democracy.

Death of Simon de Montfort from ‘Chronica Roffense’ by Matthew Parris, early 14th century. (

The British Library/HIP/Topfoto

)

Château Gaillard: the magnificent castle built on the Seine by Richard I to protect the Norman border with France. Supposedly unconquerable, it was taken from John by Philip II Augustus in 1204 during the fall of Normandy.

Chateau Gaillard. (

© Eye Ubiquitous/Superstock

)

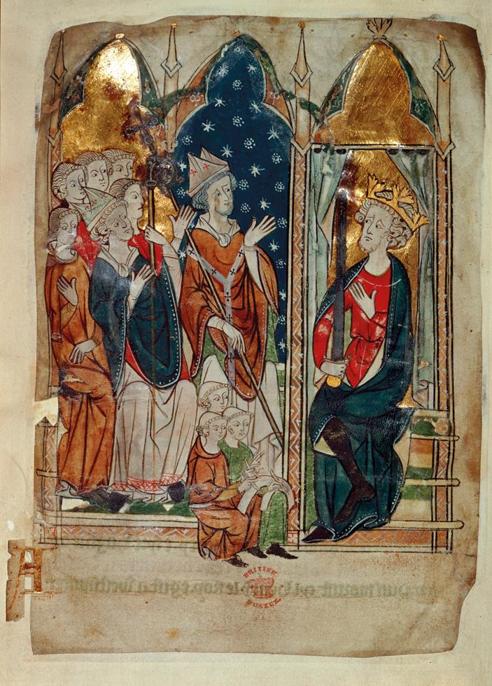

Edward I, a legal reformer and Hammer of the Scots, was the most physically intimidating of the Plantagenet kings. Tall and fierce-tempered, it was said that he once scared a man to death. Here, seemingly in milder mood, he addresses his court. He holds a sword of conquest, while tonsured clerks take note of his utterances.

Edward I at court from Miscellaneous chronicles,

c

.1280–1300. (

akg-images/British Library, Ms. Cotton Vitellius A. XIII, fol.6 v

)

Edward I built a ring of expensive fortresses to enforce his conquest of Wales. Conwy was completed in 1287. The castleworks and town fortifications cost around £14,500. In 1399 Richard II met the earl of Northumberland at Conwy to negotiate the relinquishing of the Plantagenet crown to Henry Bolingbroke.

Conwy Castle. (

© Buddy Mays/Alamy

)

Edward II never grasped the art of kingship. He was mocked and feared in equal measure, and surrounded himself with loathsome favourites, including Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger. His tomb (pictured) is in Gloucester Abbey, rather than the Plantagenet mausoleum at Westminster.

Tomb effigy detail showing face of Edward II. (

© Angelo Hornak/Corbis

)

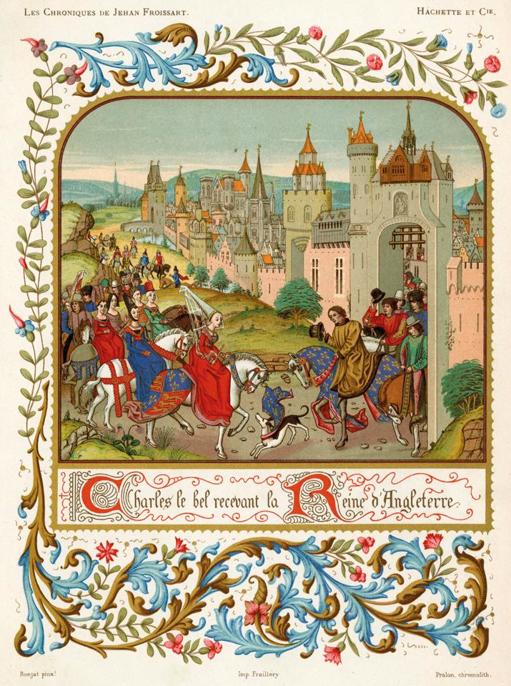

Isabella of France, queen consort of England, was known as the She-Wolf of France. Her father and all three of her brothers were French kings. With her lover Roger Mortimer she helped topple her husband Edward II from the English throne, and then ruled England for three years in the name of her son Edward III.

Isabella of France, Queen Consort of England, from ‘Chroniques’ by Jean Froissart 1337–1400. (

Mary Evans Picture Library

)

The Wilton Diptych shows Richard II as he saw himself: divinely anointed and protected by the saints, including the Virgin Mary, Edward the Confessor, John the Baptist and St Edmund.

‘The Wilton Diptych’,

c

.1395–99. (

© The National Gallery, London/Scala, Florence

)

Medieval naval battles were rare and, when they did occur, chaotic. Nevertheless, the battle of Sluys in June 1340, depicted here, was one of the first English successes in the Hundred Years War.

The Battle of Sluys from ‘Chroniques’ by Jean Froissart, 1337–1400. (

White Images/Scala, Florence

)