The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron (65 page)

Read The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron Online

Authors: Howard Bryant

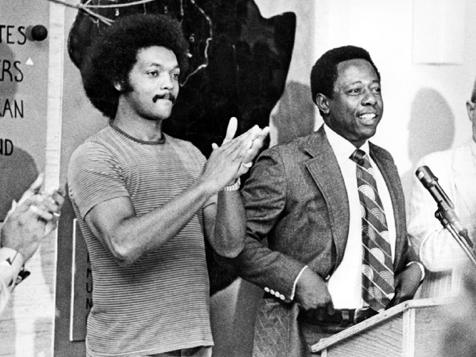

Home run no. 703. By nature, Henry did not offer entry into his inner circle. The exception was Dusty Baker (number 12), whom Henry adopted as a mentee, just as Bill Bruton had done with him years before. Davey Johnson is standing behind Baker.

With Rev. Jesse Jackson during the height of the home-run chase

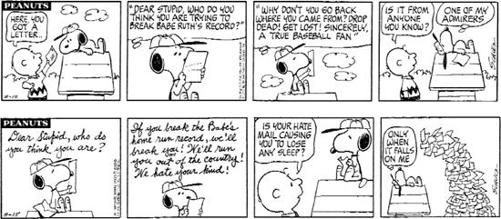

By 1973, Charles Schulz’s comic strip

Peanuts

was appearing in nearly a thousand newspapers nationwide. Perhaps no other individual was as adept at capturing the country’s attitude. As Henry approached Ruth, Schulz inserted him into the strip during the week of Aug. 10–17, 1973, solidifying his place at the center of the national conversation.

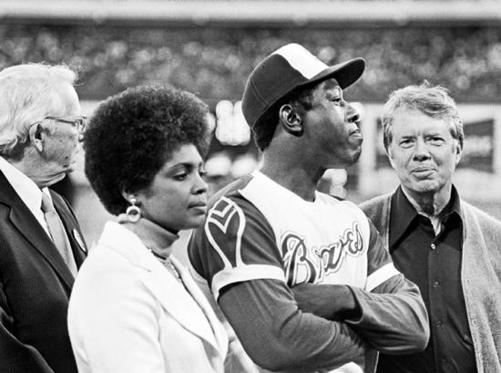

With his second wife, Billye, and Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, on April 8, 1974, hours before he broke Babe Ruth’s thirty-nine-year-old home-run record. Carter would say that Henry Aaron “did as much to legitimize the South as any of us.”

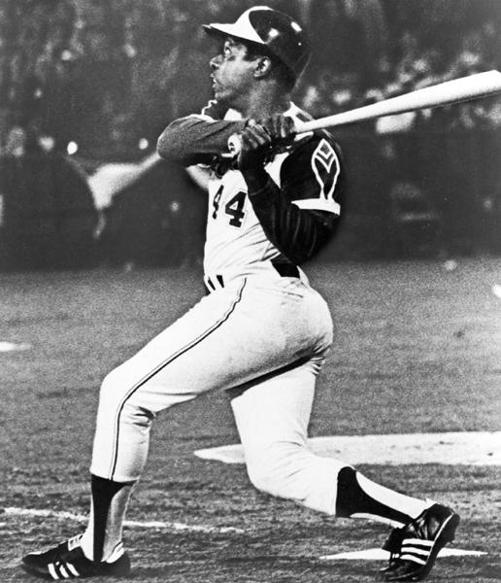

Henry at the summit. Widely considered the greatest moment in the history of the game, April 8, 1974, the night Henry broke Babe Ruth’s record, would hold only bittersweet moments for him. He would not talk often about that night or reflect easily. “What should have been the best time of my life was the worst, all because I was a black man. Something was taken from me I’ve never gotten back.”

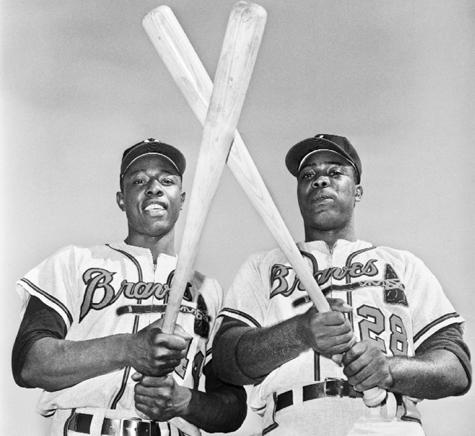

Outgoing and gregarious, Tommie Aaron (right) joined the Braves in 1962. No other teammate could bring out the lighter side in Henry like his younger brother. Tommie had been forecast as one of baseball’s first African American managers in the major leagues, until leukemia ended his life in 1984.

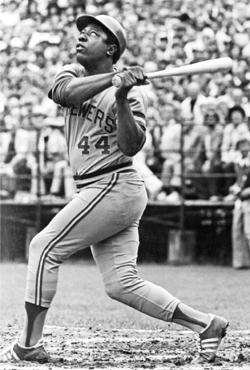

Henry Aaron said he would never be one of those players who hung on past his prime, yet in two years with Milwaukee he hit .232, with 22 home runs and 95 RBIs. “There’s something magical about going back to the place where it all began … Everybody wants to turn back the clock. But I discovered the same thing that Ruth, Hornsby, and Mays did: you can’t do it.”

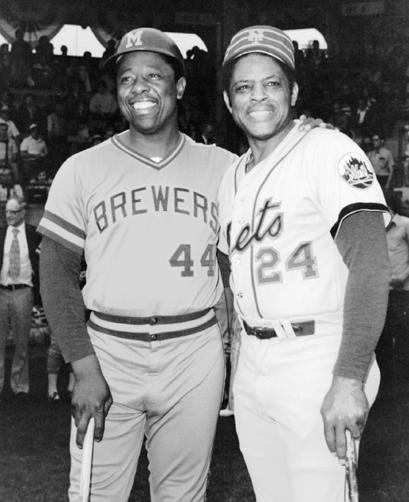

Henry, in his final year in the big leagues, with Willie Mays, then a coach with the New York Mets, at an exhibition game. The two held a fierce rivalry as players, but in the next chapter of their lives Henry would escape the shadow of Mays with significant successes in the business and philanthropic worlds.

Henry and Billye in front of his plaque at the Hall of Fame. Henry Aaron and the Hall of Fame did not enjoy an easy relationship. Following his induction in 1982, he would return exactly once over the next sixteen years. Only a greater appreciation of his skills and depth by a new administration healed the wounds.

Henry had always considered himself a mama’s boy, but while his features resembled those of his mother, Stella, his unpretentious approach to work was a paternal trait that would forever define the son.

Despite his accomplishments, Henry Aaron never wanted to be defined by baseball. “I want it,” he said, “to be a part of my life, not the whole thing.” It was his friendship with President Bill Clinton that began to elevate him from baseball great to American icon.

In June 2002, Henry flew to San Francisco to celebrate Barry Bonds’s 600th home run. The two had been cordial in the past, even friendly, but the growing scrutiny over Bonds’s use of performance-enhancing drugs in pursuit of the all-time home-run record forever strained the relationship.