The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron (66 page)

Read The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron Online

Authors: Howard Bryant

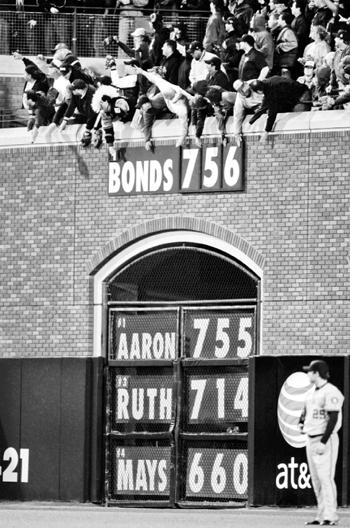

For thirty-three years, Henry Aaron stood alone at the top of baseball’s all-time home-run record. On August 7, 2007, Bonds replaced him at the top of the numerical list, but not the emotional. “Bonds may have the record,” Reggie Jackson said, “but people still believe in Henry. He’s the people’s home-run champion.”

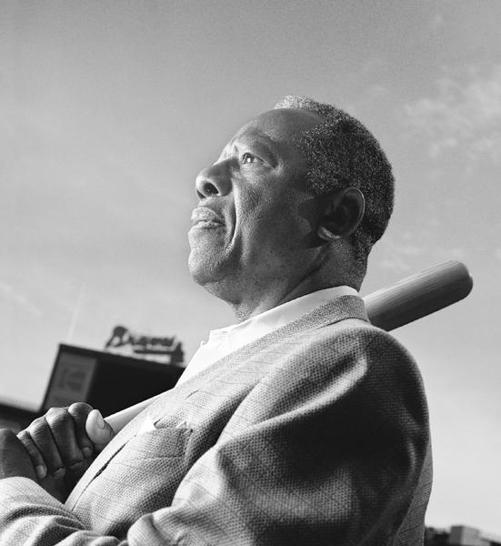

For much of his public life, Henry had been considered distant, brooding, and embittered, but it was his bursting smile, generosity, and dry wit—a side of him suffocated by the demands of fame and his discomfort with celebrity—that his inner circle of friends recalled fondly.

Henry Aaron

With that, Henry rejoined the Braves, but it likely would not have happened without Ted Turner. Henry, Turner told him, would have a job for life with the Braves. Henry’s official position was director of minor-league personnel. He would oversee the 125 players the Braves farmed out through the five clubs, from A ball to Triple-A. He would be paid fifty thousand dollars annually. Five years after Jackie Robinson’s death, Henry became the first black ex–major-league player making front-office player-personnel decisions for a major-league club.

Paul Snyder worked closely with Henry during those years as director of minor-league personnel. Snyder recalled that early on he sensed a certain tension between them, now that he was Henry’s peer. Henry, Snyder believed, understood that there were those within the Braves management who did not want him to have the job and thus were interested in undermining his success. Henry responded by being outwardly withdrawn—which is to say, polite but distant.

“We were sitting back in our conference room

280

in our old stadium, at Fulton County. I was sitting straight across from him. He was being a little bit distant to me,” Snyder recalled. “I assured him I didn’t want his job. I had a job. I was strictly trying to help him. I was trying to make the best decisions for him and for the Braves. I had a department to run. We weren’t spending a lot of money on scouting, so we had to make the most of our decisions.

“From that day forward, I felt better. Inside of that first year, he was still trying to figure out who was on his side and who wasn’t. I was a minor leaguer. He didn’t have to worry about me.”

F

OR A SHORT

time, Henry seemed to embody the next stage of the Robinson mission. In addition to him, there was Bill Lucas, who was the Braves general manager. Lucas and Henry were not always on the best terms after the divorce, and Henry would admit that the relationship could be tense at times, but they maintained a mutual and professional respect. Meanwhile, Henry’s sister Alfredia had married David Scott, a rising member of the Georgia House of Representatives.

Not only was Lucas an executive; he had begun to create opportunities for others to have upper-management positions. Though Bill Lucas and Henry were no longer connected by marriage, they had known each other since Bill was a freshman in college in early 1953 at Florida A&M. After that, Lucas was a Braves prospect, until, during a minor-league game, he attempted to beat out an infield hit and crashed into the first baseman. Lucas blew out his knee and his career ended.

Then, in 1979, while watching a Braves game on television, Bill Lucas suffered a severe brain aneurysm. He was admitted to Emory Hospital for five days but never regained consciousness. He was forty-three when he died.

T

OMMIE

A

ARON

retired as a player in 1971. He had played parts of seven seasons in the minors and had been named Most Valuable Player at Richmond in the International League in 1967. He had worked in the organization as a player, a roving hitting instructor, and a minor-league coach. Upon taking the job, Henry pushed for Tommie to become manager of the team’s top farm club, Triple-A Richmond. There was even talk that Tommie Aaron could become a big-league manager. By 1981, only three black men had managed a big league club and none of them—not Frank Robinson, nor Larry Doby, and nor Maury Wills—lasted more than three seasons.

Tommie had served as a big-league coach since 1979, first under Bobby Cox and then in 1982 under Joe Torre, another of Henry’s old teammates who became a manager. It was with Torre that Tommie headed for spring training as routinely as he had for the previous twenty-five years. Only this time, following his annual physical, it became apparent something was wrong.

“He went to spring training.

281

They did the normal blood work, and something wasn’t right,” Carolyn Aaron recalled. “They told him he had a certain type of anemia. That turned into the leukemia.”

As much as Henry, Tommie Aaron was a member of the Braves family. Where Henry had been serious and unsure, Tommie Aaron was loose and gregarious, thought Paul Snyder.

“He played all over our system. He loved shooting craps. I remember him in that rinky-dink clubhouse in Eau Claire,” Snyder said. “He loved to roll the bones. Tommie had a lot of ability. He could play six or seven positions, everything but catch. He was very genuine.”

Tommie Aaron was the one person who had bridged that gap with Henry, perhaps, apart from Billye, better than any other person in Henry’s life. Henry possessed a deep laugh, and a broad, engaging smile, but it was Tommie who, friends said, was able to make Henry laugh from his insides, deep from his gut. Tommie could swear and joke and loosen Henry up in public to the point where, around Tommie, Henry Aaron was a different person.

“He was just so different from Hank. Hank was so reserved,” Carolyn Aaron remembered. “He was so outgoing. All the kids on our street in Mobile would come to the house and Tommie would be the one to take them to the Mardi Gras parade. He would be out raking the yard and the kids would always be there. He taught them baseball. The kids in the neighborhood talked to Tommie more than their own fathers.”

Every day for over two and a half years, both at home and at Emory Hospital, it was Henry who came by with food, who called every day. Periodically, there would be hope of remission, only to have the disease return anew. On August 16, 1984, eleven days after his forty-fifth birthday, Tommie Aaron died. Henry was at the hospital that day, broken. And it was there that Carolyn watched Henry Aaron burst, his right fist slamming into the reinforced hospital window.

“It upset Hank very much. Everybody jumped when he hit that glass window,” Carolyn recalled. “It was normal to grieve, normal to cry. I can’t remember when I stopped crying, but when I was in public, no one knew my heart was just broken. Then, one day, you wake up and you say, ‘I didn’t cry today.’”

B

Y TEMPERAMENT

, Henry was not an orator or an activist. He preferred to work through channels and to collaborate. His commitment was solid, but he did not need to be in front of the camera, at the top of the headlines. He had, in fact, discovered that very little good came from taking a personal, public stance, and his edgy relationship with the press always seemed to intensify. Behind the scenes, he lent his name and gave his time to fight teenage pregnancy, a topic most professional athletes would avoid. What made Henry’s approach even bolder was his announcement that he would do a speaking tour of high schools on behalf of Planned Parenthood. On a Sunday morning, April 30, 1978, Henry arrived at Grady Memorial Hospital to lend support to a national conference on teenage sex and sexuality. After the buzz caused by his presence had subsided, Henry listened attentively to the figures: The hospital had delivered an average of six hundred babies per year between 1967 and 1977 to girls whose age ranged from twelve to sixteen. The staff told Henry that two-thirds of teen pregnancies were unwanted and that a third of all abortions in the United States were performed on teenagers. At the press conference announcing his involvement, Henry took the podium and took a prepared text from its folder.

“Something’s got to be done about it,”

282

he said. “Young boys are talking about ‘scoring’ on dates every day. When you’ve gone all the way, you’ve scored. But I want to tell you something … you’re not a champion in my book if you cause a young girl who doesn’t want to become pregnant to become pregnant and have to drop out of school.” In meeting with the Grady doctors, Henry took a modern approach toward sex education. Kids did not need to be lectured about sex, he said. “They need to know what they’re doing when they do it, and accept the responsibility.”

He was applauded for his principles and commitment.

But when he stepped too far out on the ledge, he was not often deft enough to avoid trouble, for he had both crafted a reputation as the mild-mannered Henry Aaron and begun to challenge conventions during a time of transition. Baseball wasn’t yet prepared for this dimension of Henry. He was tired of being slapped in the face.

In 1977, a month before Henry’s forty-third birthday, Fred Lieb, who had been writing about baseball since the Dead Ball Era, listed his all-time team over the past one hundred years. Lieb was white, born in the previous century, weaned on the game when it did not include blacks, and his list reflected as much: It did not contain the name of a single black player. Bill Dickey, Lou Gehrig, Eddie Collins, Honus Wagner, Pie Traynor, Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Babe Ruth represented Lieb’s position players. Cy Young, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, Bob Feller, Lefty Grove, and Sandy Koufax were his pitchers. As far as other writers were concerned, it was Henry who seemed the clearest omission, and they questioned Lieb about this.

NO PLACE FOR AARON WITH ALL-TIME

STARS. AARON NOT AN ALL-TIMER?

283

“I was fully aware of the racial question,” Lieb told the

Chicago Tribune

. “I had to ponder for a long time about leaving off such great players as Hank Aaron, who has broken many of the records of both Ruth and Cobb; the fantastic Willie Mays and Jackie Robinson. However, I have to be true to my convictions. Having seen most of the great players, past and present, I honestly believe this is the best team one could field.”

While his friends could not understand why Henry would let a dinosaur like Fred Lieb—an unimportant man from another century—get to him, Henry broiled. And some friends also wondered why the attention of a stuffed shirt like Bowie Kuhn meant so much to him. There was one problem with that elevated logic: It mattered to

him

. To Henry, this was just another injustice, another way to slight him for surpassing Ruth. Billye would attempt to soothe Henry’s ire, but his anger was inspired not so much by Lieb as by an accumulation of slights.

D

AYS BEFORE

Willie Mays was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1979, Henry gave an interview with Doug Grow of the

Minneapolis Star Tribune

regarding his pessimistic outlook about opportunities for blacks in baseball. Henry, perhaps thinking of Bowie Kuhn at the time, or the black players of his day who were now retired and could not get a job in the front office, was withering in his criticism of the sport.