The History of White People (42 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

Three years older than his wife and another Mayflower descendant, Stanley Benedict had earned a Ph.D. in biochemistry from Yale in 1908. He was a single-minded, persistent, and rigid man who opposed her working outside their home. On vacations at Lake Winnipesaukee, in New Hampshire, Stanley was wont to race about in a motorboat; Ruth preferred paddling a canoe.

20

Nor did home life suit her. Sitting about their suburban home while he commuted to Cornell Medical School in New York City, she wrote biographies of feminist authors that went nowhere. Houghton Mifflin’s rejection of her life of Mary Wollstonecraft in 1919 only steeled her resolve for further study, first a class with the philosopher John Dewey at Columbia, then more at the fledgling New School for Social Research.

At the New School, Benedict studied gender in many different cultures with the wealthy and well-connected anthropologist Elsie Clews Parsons, a Columbia Ph.D. and a member of the Boas circle. Benedict’s abilities impressed Parsons, and she and another of Benedict’s New School instructors took her to meet Boas. Waiving the regular requirements, he admitted Benedict into Columbia’s Ph.D. program in anthropology during the spring of 1921. Benedict was thirty-three; Boas, sixty-three.

21

The two remained close collaborators, running the Columbia Department of Anthropology together until his (forced) retirement in 1936.

By the fall of 1922, Benedict was serving as Boas’s teaching assistant, often guiding Barnard undergraduates around the American Museum of Natural History. One such student was Margaret Mead (1901–78), who had moved to New York City to be near her fiancé, a student at the Union Theological Seminary. But Benedict’s enthusiasm for anthropology galvanized Mead. She became Mead’s mentor, and she and Boas persuaded Mead to switch from psychology to anthropology for graduate school, to do work “that matters.” The Benedict-Mead relationship steadily deepened, moving from teacher-student to colleague-colleague to friends, lovers, and lifelong intellectual collaborators. When Mead’s daughter was born in December 1939, Benedict was in California writing her book on race and had been separated from her husband for nine years. She crocheted booties and sent them to the baby.

22

The bond between Mead and Benedict even outlasted Benedict’s death in 1948.

23

Mead served as Benedict’s literary executor and published two books about her.

24

Looking back, Mead recalled Benedict as a “very shy, almost distrait [absentminded], middle-aged woman [she was thirty-four years old] whose fine, mouse-colored hair never stayed quite pinned up. Week after week she wore a very prosaic hat and the same drab dress…. She stammered a little when she talked with us and sometimes blushed scarlet.”

25

Benedict always thought of herself as a misfit but also suspected that her deviance nourished her intellectual creativity.

26

As Mead reports in her autobiography,

Blackberry Winter: My Earlier Years

, Benedict was subject to depressions and migraines. She “expected the worst from people and steeled herself against it.”

27

And Benedict was indeed a misfit, but not one of her own making. There was the question of gender: here was a Columbia professor with a Columbia doctorate who was not appointed assistant professor until 1931, after a dozen years of teaching, advising dissertations, and publishing a best-selling book. She had also served as editor of the

Journal of American Folklore

for seven years. In 1936 she finally rose to associate professor, but not to full professor until 1948, after being elected president of the American Anthropological Association.

Outside of Columbia, by contrast, Benedict reigned as a leader in her scholarly field and as the public face of anthropology. She wielded enormous power both across the United States and especially among New York’s intelligentsia.

28

In the 1920s she had begun an active career explaining anthropology to non-anthropologists, publishing articles in the

Nation

, the

New Republic

,

American Mercury

,

Scribner’s

, and

Harper’s

. Mead saw her as anthropology’s “press committee,” a one-woman popularizing force.

29

No wonder she felt conflicted!

Actually, Mead arrived first. Fifteen years younger than Benedict, Mead jumped onto best-seller lists in 1928 with

Coming of Age in Samoa

, a study of women’s adolescence stressing cooperation over competition, but also offering sexual titillation. Six years later, Benedict’s first book,

Patterns of Culture

, also thrived, particularly after publication of a cheap paperback edition in 1946. By the 1980s it had sold nearly two million copies and been translated into twenty-one other languages. Even today,

Patterns of Culture

introduces anthropology to the lay public by touting the importance of culture over biology and of culture as learned behavior, as “personality writ big.”

The book describes three cultures, the Zuni of the American Southwest, the Kwakiutl of the American Northwest, and the Dobu of the Pacific Islands. Borrowing terminology from Friedrich Nietzsche, Benedict labels the Zuni as serenely Apollonian; the Kwakiutl she saw as violently Dionysian; and the Dobu were just plain paranoid.

*

Starkly contrasting behaviors, Benedict divides these groups according to culture, not by race. This message, then, focuses on the possibility of change, for culture, not transmitted biologically, changes over time, while race presumably is a permanent condition. Intriguingly, however, Benedict could not escape her own class and culture. She slips phrases into

Patterns of Culture

that place herself and her presumptive readers squarely in the Nordic column. Arguing generally against race prejudice in her introductory pages, she deplores the drawing of “the so-called race line” against “our blood brothers the Irish.” Across this imagined race line, French face off against Germans, “though in bodily form they alike belong to the Alpine sub-race.”

30

Old habits of thought died hard, even within the Boas circle.

During the 1930s Benedict did all the work of a senior scholar. She also ran the Columbia anthropology department, though without a title, since the university administration could not imagine a woman as departmental chair. Things worsened under Boas’s replacement, Ralph Linton, who disliked Benedict and soured the department’s atmosphere against her. (After she died, Linton flashed a Melanesian charm, bragging that he had used it to cause her death.)

31

Old, exhausted, and ill, Boas still came to the department once or twice a week, but events in Germany increasingly preoccupied him. At first Benedict deplored his giving up “science for good works,” calling it a waste of scholarly energy. But as the Nazis stepped up their anti-Semitic persecution, she came to share Boas’s distress and joined his antiracist activism.

32

Nazi violence awakened many an American intellectual, so Benedict’s antiracist work stands for a gathering tendency among scholars. More and more, Nazi anti-Semitism wrenched them away from the idea of a Jewish race, and even from drawing racial lines among any Europeans and their progeny.

While on sabbatical in Pasadena in 1939, Benedict wrote

Race: Science and Politics

(1940), a book widely praised for its clear explanation of anthropology’s thinking about race but ultimately confused and confusing. In the first edition, Benedict speaks as an anthropologist sorting out for laymen the differences between race and racism. “Race,” Benedict explains on the foreword’s first page, “is a matter for careful scientific study; Racism is an unproved assumption.” The text carefully distinguishes hereditary, biological race from the learned behavior of culture and language. Culture does not depend on race, and Italians, Jews, and the British are not races. There is no such thing as Nordic civilization.

33

Given the continuing allure of scientific racism, Benedict is presenting a useful summary. But

Race: Science and Politics

is very much of a piece with its time, a statement crafted in the long shadow of the anthroposociology of Georges Vacher de Lapouge—whom Benedict confronts by name on the first page of the main text—and totally in the thrall of cephalic indices, Nordics, Alpines, and Mediterraneans.

34

She was trying to dig out of a very deep race hole, and she could get only halfway into clarity, as befit the confusions of her era.

For all its fine intentions, this book contains predictable contradictions. As in the early twentieth-century ways of thinking about race,

Race: Science and Politics

hardly touches on non-Europeans. The “races” in question are mainly white, as though all Americans descended from Europeans and African Americans hardly counted. Benedict translates “white race” as

Nordics

and “other varieties” as “

Alpines, Mediterraneans

.” She says Europeans are too mixed to be separated by race, then continues to separate the three “subdivisions” of the Caucasian race as Nordic, Alpine, Mediterranean, as distinguished by hair texture, head form, skin pigment.

This echoes William Z. Ripley in 1899, but with a difference that poses a problem: Benedict admits that none of these traits actually correlates with these subdivisions. So Ripley’s categories no longer apply. For Benedict, only three great races actually exist, “Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and Negroid.” They are most “definite,” but—oh-oh—Boas, she admits, has his doubts and sees just two: Mongoloid, which includes “Caucasic,” and Negroid.

35

Later editions grew even murkier.

After the United States entered the war in December 1941, Benedict revised

Race

by taking nonwhites more fully into account. Now Benedict speaks as the citizen of a belligerent power whose allies include Asians and Africans.

36

Nazism has heightened her awareness of American racism, which she mentions in the foreword to the 1945 edition. By now “race” in her eyes includes African Americans as well as the descendants of Europeans.

In all three editions of

Race: Science and Politics

, Benedict speaks as a Mayflower descendant, a stance Boas had actually recommended in order to lend her book an aura of disinterested fairness. In 1940 she writes as “those of us who are members of the vaunted races and descendants of the American Revolution.” In 1943 and 1945 she says, “We of the white race, we of the Nordic race, must make it clear that we do not want the kind of cheap and arrogant superiority the Racists promise us.”

37

This assumed bond between author and readers harks back to the early 1900s, when New England ancestry was supposed to confer intellectual soundness and readers were thought to belong to the same elevated class. That would mean a narrower, rather than a wider, readership. With the war, however, widening the readership for antiracist thinking became more important.

Between new editions of

Race: Science and Politics,

Benedict collaborated with a Columbia colleague, Gene Weltfish, on a 32-page, ten-cent pamphlet,

The Races of Mankind

(1943). Aimed at schools, churches, YMCAs, and USOs,

Races of Mankind

denounces racial chauvinism, quoting both racists and antiracist experts and explaining that “no European is a pure anything” and that “Aryans, Jews, Italians are

not

races.”

Describing the actual existence of race as a meaningful category of analysis, Benedict and Weltfish were not willing to go as far as the literary critic Jacques Barzun and the anthropologist Ashley Montague. In 1937 Barzun had published

Race: A Study in Superstition

, whose title says it all.

*

Montague’s 1942

Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race

called the idea of race “the witchcraft of our time.”

38

Both these books sold well in multiple editions, but social scientists worldwide could not agree. (Even the antiracist UNESCO statement on race [1952] retained the notion that races actually do exist.)

39

Benedict and Weltfish were writing from within the scientific mainstream, confused as it was at the time.

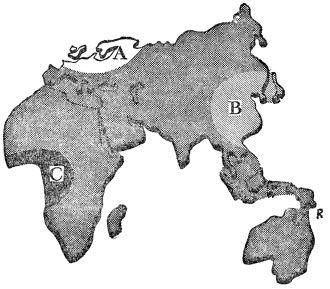

For Benedict and Weltfish there were three and only three races: the Caucasian race (A), the Mongoloid race (B), and the Negroid race (C). Their map shows where these three races are located. (See figure 24.2, “Most people in the world have in-between-color skin.”) The Caucasoids are in northwestern Europe (not Mediterranean Europe); the Mongoloids occupy a semicircle in eastern Asia (but not Southeast Asia, Siberia, or Mongolia); Negroids are grouped around the Bight of Benin (not the rest of northern, Saharan, southern, or eastern Africa). Everyone else, presumably, has “in-between-color skin.” Attractive though it might be, this map leaves everything to be explained about race in America, where people from four continents were having sex and producing American babies.

40