The History of White People (19 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

The Germans were a heterogeneous group in terms of wealth, politics, and religion. Settling largely in the Midwest in the “German Triangle” of Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, they stirred relatively little controversy, compared with the outcry against the Irish.

18

For one thing, German Americans had been blending into Protestant white American life since before the Revolution, and many had climbed to the top of the nation’s economic ladder. Johann Jakob Astor, for instance, born near Heidelberg in 1763 and immigrating to the United States in 1784, was the richest man in the United States at his death in 1848. In the nineteenth century the Radical Republican Carl Schurz and the railroad magnate Henry Villard also presented a certifiably loyal image of middle-and upper-class German Americans.

*

Schurz had joined hundreds of other Germans turning to the United States after the failed revolutions of 1848. A taint of radicalism might dog them locally, but only sporadically did German radicalism raise the alarm on a national scale. The Catholic Irish were something else entirely.

S

OME FIFTY

thousand Irish lived in Boston by 1855, making the city one-third foreign born, the “Dublin of America.” There they found low-paying work in manufacturing, railroad and canal construction, and domestic service. Before long, Irishmen had gained a sorry reputation for mindless bloc voting on the Democratic (southern-based and proslavery) ticket, and also for drunkenness, brawling, laziness, pauperism, and crime. All these defects attached to the figure of “the Paddy.”

When Ralph Waldo Emerson, the leading American intellectual before the Civil War, casually referred to poor Irishmen as “Paddies,” he drew upon stereotypes of improvidence and ignorance as old as Sir Richard Steele’s 1714 description of “Poor Paddy,” who “swears his whole Week’s Gains away.”

19

As a young minister in the late 1820s, Emerson posited a multitude of inferior peoples that included Irish Catholics. Cataloging the traits of backward races, he set stagnation atop the list, as though stagnation ran in the blood of human beings. Over the years Emerson’s cast of incompetent races would rotate indiscriminately around the globe, but two peoples nearly always figured: the African and the Irish. In a very early musing, Emerson actually expels the Irish from the Caucasian race:

I think it cannot be maintained by any candid person that the African race have ever occupied or do promise ever to occupy any very high place in the human family. Their present condition is the strongest proof that they cannot. The Irish cannot; the American Indian cannot; the Chinese cannot. Before the energy of the Caucasian race all the other races have quailed and ser done obeisance.

That was in 1829. Nothing had changed by 1852, when Emerson wrote,

The worst of charity, is, that the lives you are asked to preserve are not worth preserving. The calamity is the masses. I do not wish any mass at all, but honest men only, facultied men only, lovely & sweet & accomplished

m

women only; and no shovel-handed Irish, & no Five-Points, or Saint Gileses, or drunken crew, or mob or stockingers, or 2 millions of paupers receiving relief, miserable factory population, or lazzaroni, at all.

20

Here we have the heart of Emerson’s view of the poor, typified by the Irish.

After the failure of the Hungarian revolution in 1848 and Lajos Kossuth’s triumphant tour as a hero in exile, Emerson found a way to view the Hungarian situation through an Irish lens: “The paddy period lasts long. Hungary, it seems, must take the yoke again, & Austria, & Italy, & Prussia, & France. Only the English race can be trusted with freedom.”

21

Emerson pontificated against Central Europeans as well as the Irish: “

Races.

Our idea, certainly, of Poles & Hungarians is little better than of horses recently humanized.”

22

Emerson would probably not have been surprised that Polish jokes abounded in the late twentieth century. Certainly during his time Paddy jokes amused the better classes, having been recycled from eighteenth-century English “jester” books. This one about the two sailors, one a dumb Irishman, lived for more than a century:

Two sailors, one Irish the other English, agreed reciprocally to take care of each other, in case of either being wounded in an action then about to commence. It was not long before the Englishman’s leg was shot off by a cannon-ball; and on his calling Paddy to carry him to the doctor, according to their agreement, the other very readily complied; but he had scarcely got his wounded companion on his back, when a second ball struck off the poor fellow’s head. Paddy, who, through the noise and disturbance, had not perceived his friend’s last misfortune, continued to make the best of his way to the surgeon, an officer observing him with a headless trunk upon his shoulders, asked him where he was going? “To the doctor,” says Paddy. “The doctor!” Says the officer, “why you blockhead, the man has lost his head.” On hearing this he flung the body from his shoulders, and looking at it very attentively, “by my soul, says he, he told me it was his leg.”

23

*

Cartoons played an important role in reinforcing the Paddy stereotype. Frequently apelike, always poor, ugly, drunken, violent, superstitious, but charmingly rascally, Paddy and his ugly, ignorant, dirty, fecund, long-suffering Bridget differed fundamentally from visual depictions of sober, civilized Anglo-Saxons. (See figure 9.1, “Contrasted Faces.”) Most Paddy phrases—such as “Paddy Doyle” for a jail cell, “in a Paddy” for being in a rage, “Paddyland” for Ireland, and “Paddy” for white person—have lost currency in today’s vernacular; only “paddy wagon” endures to link Irishmen to the American criminal class.

Fig. 9.1. “Contrasted Faces,” Florence Nightingale and Bridget McBruiser, in Samuel R. Wells,

New Physiognomy, or Signs of Character, Manifested through Temperament and External Forms, and Especially in “The Human Face Divine”

(1871).

A

MERICAN VISUAL

culture testifies to a widespread fondness for likening

the

Irishman to

the

Negro. No one supplied better fodder for this parallel than Thomas Nast, the German-born editorial cartoonist for

Harper’s Weekly.

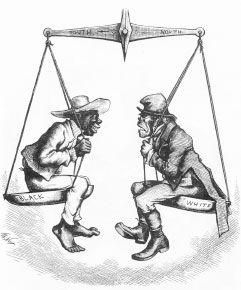

In 1876, for instance, Nast pictured stereotypical southern freedmen and northern Irishmen as equally unsuited for the vote during Reconstruction after the American Civil War. (See figure 9.2, Nast, “The Ignorant Vote.”)

This cartoon does two things at once: It draws upon anti-Irish imagery current in Britain and the United States, and depicts both figures in American racial terms. Bumpkin clothing and bare feet mark the figure labeled “black” as a poor rural southerner, while the face, expression, and lumpy frock coat of the “white” figure are stereotypically Irish. It is important here to recognize that the Irish figure is not only problematical but also, and most importantly, labeled white. Nast drew for a Republican journal identified with the struggle against slavery. However, figures on the other side of the slavery issue could just as easily draw the black-Irish parallel. James Henry Hammond, nullifier congressman, U.S. senator, and governor of South Carolina, denounced the British reduction of the Irish to an “absolute & unmitigated slavery.”

24

And George Fitzhugh in

Cannibals All! or Slaves without Masters

(1855) intended his Irish comparisons to prove that enslaved workers fared better than the free.

25

Fitzhugh hardly meant to recommend freedom to either poor community.

Fig. 9.2. Thomas Nast, “The Ignorant Vote—Honors Are Easy,”

Harper’s Weekly,

1876.

Abolitionists saw the other side of the coin, frequently championing kindred needs for emancipation. In the 1840s, Garrisonians made Irish Catholic emancipation an integral part of their campaign for universal reform. Visiting the United States, Daniel O’Connell (1775–1847), the first Catholic since the Reformation to sit in the British House of Commons, the leading Irish champion of Catholic emancipation, and an indefatigable campaigner for Irish independence, saw the needs of starving Irish and enslaved blacks as analogous. The American abolitionists Wendell Phillips and Frederick Douglass adopted the same rhetorical ploy. In a visit to Ireland in the famine year of 1845, Douglass likened the circumstances of Ireland’s poor to those of enslaved black people. Such a tragic physiognomy of the two peoples wrenched his heart: “The open, uneducated mouth—the long, gaunt arm—the badly formed foot and ankle—the shuffling gait—the retreating forehead and vacant expression—and their petty quarrels and fights—all reminded me of the plantation, and my own cruelly abused people.” The Irish needed only “black skin and wooly hair, to complete their likeness to the plantation Negro.”

26

For Douglass and other abolitionists, the tragedy of both peoples lay in oppression. Neither horror stemmed from weakness rooted in race.

One group, however, utterly repudiated the notion of black-Irish similarity, and that was the Irish in the United States. Irish immigrants quickly recognized how to use the American color line to elevate white—no matter how wretched—over black. Seeking fortune on the white side of the color line, Irish voters stoutly supported the proslavery Democratic Party. By the mid-1840s, Irish American organizations actively opposed abolition with their votes and their fists. In the 1863 draft riots that broke out in New York and other northeastern cities, Irish Americans attacked African Americans with gusto in a bloody rejection of black-Irish commonality. In Ireland and in Britain, too, cultural nationalists seeking to shed racial disadvantage counterattacked, forging a Celtic Irish history commensurate with that of Anglo-Saxonists.

*

While Ireland’s political struggle for independence from Britain delayed an Irish dimension of the Celtic literary revival until late in the nineteenth century, political Irish nationalism had flourished long before the struggle for Irish independence succeeded in 1921. Irish nationalists could turn Saxon chauvinism inside out in ways similar to those of abolitionists like David Walker. In 1839 Daniel O’Connell won over American abolitionists’ hearts with a scathing condemnation of American imperialism. Abolitionists advocated peace, as expansionists were lusting after a seizure of Mexican territory: “There are your Anglo-Saxon race! Your British blood! Your civilizers of the world…the vilest and most lawless of races. There is a gang for you!…the civilizers, forsooth, of the world!”

27

For O’Connell, Anglo-Saxons were nothing but natural-born thieves. At the same time, two non-Irish litterateurs laid a basis for the study of Celtic literature.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the French philosopher Ernest Renan (1823–92) and the English cultural critic and poet Matthew Arnold (1822–88) offered admiring portraits of the mystic, romantic, and doomed Celtic race in

Poetry of the Celtic Races

(1854) and

On the Study of Celtic Literature

(1866). Renan was a highly respected philosopher of religion, Arnold, one of Britain’s leading poets and literary critics. Their works, both very mixed blessings, were evidently meant to be affectionate. But in praising the Irish closeness to nature as a salutary counterweight to Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic modernity, Renan and Arnold reduced them into dumb, pathetic natives.