The History of White People (37 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

It is not by accident that Brigham substitutes “Nordic” for Ripley’s “Teutonic,” because Brigham owed a substantial debt to Madison Grant’s

Passing of the Great Race, or The Racial Basis of European History

. First published in 1916, substantially revised in 1918 and in 1921,

The Passing of the Great Race

sold well over a million and a half copies by the mid-1930s. Grant uses “Nordic” instead of “Teutonic” in order to include Irish and Germans within the superior category but not Slavs, Jews, and Italians.

23

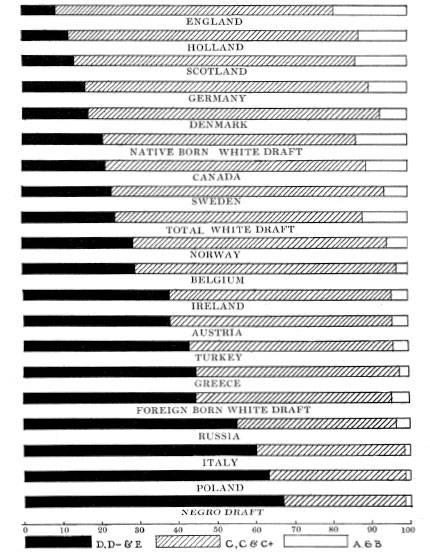

Fig. 20.2. Brigham’s bar graph of mental test results, in Carl C. Brigham,

A Study of American Intelligence

(1923).

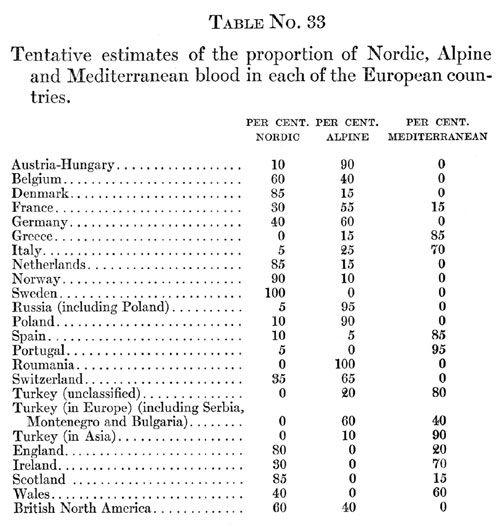

This astonishing table offers nonsensical estimates of national “blood,” presumably on the basis of cephalic indices, without explaining its methodology, which Brigham drew from one of eugenicists’ favorite theorists, Georges Vacher de Lapouge. Lapouge had displayed a similar table showing “proportions of blood” according to cephalic indexes in several countries (distinguishing northern Germans from southern Germans) in his

L’Aryen: Son rôle social

(

The Aryan: His Social Role

) in 1899.

24

*

For his part, Brigham in 1923 tabulated the (European?) population of “Russia (including Poland)” at 5 percent Nordic and 95 percent Alpine, while “Poland” is 10 percent Nordic and 90 percent Alpine. With three different subject lines, Turkey is 40, 80, and 90 percent Mediterranean, as though its regions could be demarcated according to “blood” and nobody ever migrated anywhere. Ireland and Wales are 70 and 60 percent Mediterranean, while England is only 20 percent Mediterranean. The high Mediterranean percentages allotted to Ireland and Wales presumably reflect the racist assumptions of John Beddoe and William Z. Ripley that the Irish and Welsh belong to a more primitive and therefore shorter, darker, and long-headed population than the English. After a war in which Germans had been stereotyped as “the Hun,” German “blood” was downgraded from heavily Nordic to majority Alpine. Given the value judgments assigned to “Nordic,” “Alpine,” and “Mediterranean,” table 33 emerges as an exquisite example of scientific racism, one of a series of attempts to combine “blood” with nation. This table intrigued social scientists, whether accepting or skeptical.

Fig. 20.3. Brigham, “Table No. 33. Tentative estimates of the proportion of Nordic, Alpine and Mediterranean blood in each of the European countries,” in Carl C. Brigham,

A Study of American Intelligence

(1923).

In 1911 the U.S. Immigration Commission, under Senator William P. Dillingham of Vermont, had issued the

Dictionary of Races or Peoples

, a handbook intended to clear up the “true racial status” of immigrants, on the basis of Ripley’s

Races of Europe

and reprinting many of his maps. Like Ripley,

Dictionary of Races or Peoples

appealed to questionable authorities like Lapouge and his German anthroposociologist colleague Otto Ammon.

25

Like most attempts to codify racial classification, the

Dictionary of Races or Peoples

tried to reconcile the warring categories of several different experts through lists of “race,” “stock,” “group,” “people,” and Ripley’s and other scholars’ races. Its mishmash of categories had left open the gap that Brigham tried to fill.

In addition to these European racial “blood” measurements, Brigham reinterpreted the correlation between immigrant test scores and length of residence in the United States. As might be expected, given the questions, the longer immigrants had resided in the United States, the higher their scores. But Brigham followed Yerkes’s reasoning, noting, then rejecting, the obvious causal relationship:

Instead of considering that our curve…indicates a growth of intelligence with increasing length of residence, we are forced to take the reverse of the picture and accept the hypothesis that the curve indicates a gradual deterioration in the class of immigrants examined in the army, who came to this country in each succeeding five year period since 1902.

26

In other words, immigrants who had been in the United States longer scored higher because they were inherently smarter, the cream of the crop, as it were, self-starters who had set out from the old country early on, while the way was still hard. Later arrivals had no such pluck. They scored lower because they belonged to inferior races who let shipping companies deliver them the easy way across the ocean. Anthroposociology’s cockamamie notions about headshape differences between urban and rural dwellers were now applied to conditions in the United States.

A

RRIVING IN

the jittery postwar era,

Study of American Intelligence

enjoyed a wide popularity that overwhelmed a few critical reviews in liberal journals. Brigham’s credibility rode on a handsome set of advantages—his Princeton Ph.D., his Princeton University Press publication, his Princeton faculty position, and financial backing from Grant and Gould. With this kind of high-level support, his book enjoyed much currency in the early 1920s as scientific proof that immigrants from southern and eastern Europe were as inherently defective as whole races of Jukes and Kallikaks. The idea played well in a country—and its Congress—roiled by economic, political, and social unrest.

*

T

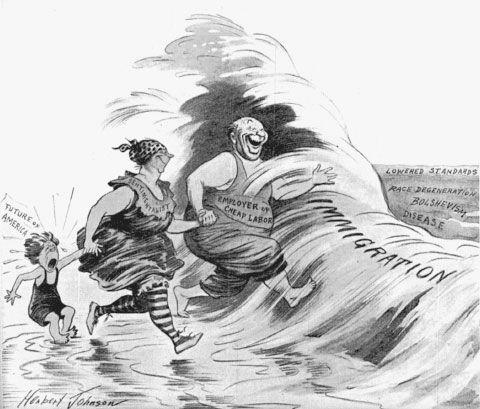

he United States stayed out of the European charnel house of war until 1917, when the conflict was already three years old. But even as American troops went to fight in Europe, the United States experienced the war less as a tragedy of trench warfare and more as a time of spiraling labor unrest and anti-immigrant paranoia. Between 1917 and 1919, a growing cycle of strikes and labor tension alarmed Americans across the political spectrum. A cartoon from the

Saturday Evening Post

, the nation’s most popular magazine, captured the all too facile coupling of immigrants, and radicalism, and race. (See figure 21.1, Johnson, “Look Out for the Undertow!”) Here Herbert Johnson, the

Post

’s regular cartoonist, depicts an American family dashing into the waves of “immigration,” grinning innocently.

1

*

The mother wears the “sentimentalist” label that hardheaded, science-minded race theorists routinely attributed to anyone—especially women—who believed that the environment played a role in human destiny. The smiling father, equally clueless, leads his family into the wave as “employer of cheap labor.” Only the child, the “future of America,” hangs back, sensing the peril ahead. Rolling in with the “immigration” wave are fatal threats to the nation—“lowered standards,” “race degeneration,” “bolshevism,” and “disease.” In this cartoon, the race in question was white, as was the menace.

Fig. 21.1. Herbert Johnson, “Look Out for the Undertow!”

Saturday Evening Post,

1921.

Republicans in Congress had been trying to restrict immigration on more or less racial grounds since the 1880s, but with limited success. Their party was, in fact, divided. Although normally allied with the Republicans, manufacturers employing cheap immigrant labor lobbied diligently against legislation to curtail it. Their economic interests weighed against a tightening of the labor market and the certainty of rising wages. The result was an unexpected alliance. Democratic presidents and congressmen representing large numbers of immigrants also resisted anti-immigration legislation as racist and discriminatory. So long as immigrants could vote—before or after naturalization—their representatives, usually Democrats, blocked much restrictive legislation.

At the center of these legislative storms were not the Irish or the Germans—they had mostly been accepted and assimilated (during the war, Germans sometimes through anxiety or intimidation). Rather, the main targets hailed from southern and eastern Europe, the masses of Slavs, Italians, and Jews, many said to be mentally handicapped, prone to disease and un-American ideologies. Therein lay the threat. Where in all this were Asians? Nowhere, for since 1882, after Chinese workers had completed the western portion of the transcontinental railroad, they had, one and all, been declared ineligible for citizenship. Not being part of the new American political economy meant that Asians lacked any influence in Congress. It took them a long time to gain parity.

*

A fundamental issue was labor: the stigmatized immigrants came as workers to feed American industry.

During the late nineteenth century, the United States had industrialized impressively. After recovery from the deep depression of the 1890s, American industrial output rivaled Europe’s. More than 14.5 million immigrants, mostly from southern and eastern Europe, entered the country between 1900 and 1920, their numbers far exceeding even the lowly Irish and Germans disdained by Ralph Waldo Emerson as “guano races.”

2

In Emerson’s time the Irish had found paying work on the canals and the eastern railroads; now immigrants poured into manufacturing, rather than farming and transportation, generating the profits of twentieth-century America.

3

By the 1890s industrialization had given rise to giant corporations like Standard Oil of John D. Rockefeller, U.S. Steel under Andrew Carnegie, and the combined Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Illinois Central railroads run by E. H. Harriman. The wealth of these corporations depended upon friendly state and federal legislators and a multitude of local corporation lawyers in the state legislatures that elected U.S. senators until 1913. Corporate-minded officeholders shaped a legal context friendly to corporations and hostile toward labor. Free to squelch workers’ attempts to organize and quick to exert the power of the state against strikers, corporations rewarded themselves with salaries, bonuses, and profits and their shareholders with dividends, rather than accord their workers wage increases. Inevitably, workers came to resent such exploitation. In the popular mind, their resentment wore an immigrant face.

Soon disruptive actions, such as the great steel strike in Homestead, Pennsylvania, in 1892 and the 1894 Pullman strike near Chicago, broke out regularly. Even voters who may have felt no particular warmth toward labor began to cast protest votes against the two major parties, both very dedicated to serving capital. In consequence, during the so-called Progressive Era before 1915, left-wing policies more attuned to the needs of people than to the wishes of powerful corporations gained favor.

The Socialist Party (SP), founded in 1901, led the way, powered by voters unhappy with the lockstep Republican and Democratic probusiness status quo. Throughout the country the SP grew quickly from around 1910, attracting some 100,000 members. One stronghold, New York City’s 1.4 million Yiddish-speaking, working-class immigrants, elected a series of socialist candidates, including ten state assemblymen, seven city councilmen, one municipal judge, and one congressman.

4

The SP candidate for president, Eugene Debs, polled a million votes in 1912, the SP’s high-water mark.

The far more revolutionary labor organization, the Industrial Workers of the World, also seized the moment, waging a media-savvy textile strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts, birthplace of American industry in the heart of symbol-laden New England. The IWW had broken away from the SP in 1905 to pursue more radical, worker-centered policies. For many anxious Americans, the SP and IWW merged into a huge revolutionary threat to American society, one identified with immigrant “alien races.” In the tense, hyper-patriotic atmosphere of wartime, any hint of labor militancy did not play well across the country.

O

NCE THE

United States became a belligerent in April 1917, war production shot up, and the labor was in many cases supplied by immigrants. Long working hours and soaring inflation ensued. Everyone complained about the high cost of living, for wages did not keep pace with spectacular price increases. The result was a tsunami wave of strikes, peaking in 1917. The IWW, though small in number, staged highly publicized actions in the West, home to large numbers of Mexican immigrants. Although native-born lumberjacks and mineworkers vastly outnumbered Mexicans in the IWW, true to the hysteria of the moment, many Americans assumed the whole organization to be aliens. It was but a short step to draconian legislation. The Immigration Act passed in February 1917 targeted the IWW specifically and labor radicalism generally, barring entry into the United States of all “anarchists, or persons who believe in or advocate the overthrow by force or violence of the Government of the United States.”

5

Vigilantes quickly took the law into their own hands; they lynched a Wobbly organizer in Butte, Montana, and in the fall federal agents raided IWW headquarters in forty-eight cities. Such federal action kept the IWW in court and on the defensive, even as strikes for more pay continued around the nation.

Meanwhile, in February and October 1917 Russia experienced a first and then a second revolution in the name of the working class. The second one, proclaiming itself Marxist, Bolshevik, and Soviet, took Russia out of the European slaughterhouse of war. Furthermore, it increased the attraction of socialism as an alternative to senseless, belligerent politics and bolstered the appeal of Marxism as a sweeping explanation for the human condition.

At bottom, Marxism touted class conflict, rather than race conflict, as the motor of history. Such a substitution of class for race did not alter Americans’ social ideology, for foundational law and the organization of government data (such as the census) still relied on categories of race. The Russian revolution did not persuade Americans to think about labor and politics in terms of class; they continued to interpret all sorts of human difference as race.

Therein lay a crisis of race ideology. If the Teutonic white peoples of Europe represented humanity’s apex, how had they reverted to savagery so easily? The African American sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois had an answer: “This is not Europe gone mad; this is not aberration nor insanity; this

is

Europe; this seeming Terrible is the real soul of white culture…stripped and visible today.”

6

In the face of the first great crisis of whiteness, saving the “real soul of white culture” became Americans’ task after the war, one imposed and accepted amid a clash of ideas and events. The Russian revolution and wave after wave of strikes converged on hereditarian concepts of permanent racial traits à la Ripley’s

Races of Europe

. The idea of the “melting pot” was already under stress when wartime anxieties tested it further.

By the armistice of November 1918, “bolshevism” in the American public mind meant the world turned upside down. In Germany a socialist revolution followed the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II, evidently spreading the red tide. Many in the United States felt themselves stuck in a bad dream, in which Bolshevik Wobblies were running things, foreign strikers were fomenting chaos, and an insurrectionary proletariat threatened to seize government, murder citizens, burn churches, and in general destroy civilization. The end of civilization meant ugly, ignorant, unwashed immigrants breeding freely—their defects innate, hereditary, and permanent—and native Americans trodden underfoot. Events of 1919 simply made things worse.

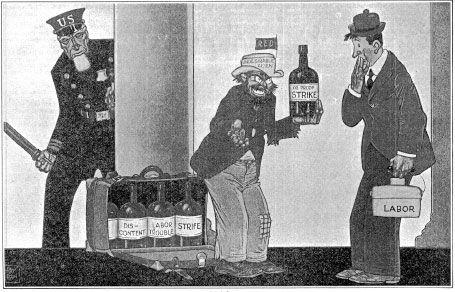

The whole world seemed in convulsion. Strikes and revolutions raged on every continent, in France and even in England. In the United States, 1919 began with a general strike of 100,000 workers in Seattle, an event that seemed so unthinkably un-American that it had to have foreign causes. Another

Saturday Evening Post

cartoon explains where strikes come from and offers a solution to the labor crisis.

7

(See figure 21.2, Roun, “100% Impure.”) A grubby, dark-skinned “undesirable alien” with a red flag in his hat for socialism, offers a potent, tempting drug, “100% proof strike” to befuddled “labor.” According to race theory’s prevailing wisdom, labor’s head shape tells a tale. It is flat in the back, thus marking him as a brachycephalic Alpine, hence bovine of intelligence and easily misled by “undesirable alien.” The valise of “undesirable alien” contains four other bottles of poison, three labeled “discontent,” “labor trouble,” and “strife.” Arriving in the nick of time to save poor, dumbfounded “labor” is a policeman labeled “US.” The solution to the labor problem caused by “undesirable alien” must therefore come from stringent federal governance.

Fig. 21.2. Ray Roun, “100% Impure,”

Saturday Evening Post,

1921.

Seattle’s general strike lasted only a week, but it was long enough to offer conservatives time to trumpet Bolshevik infiltration right here at home, which mounting strikes seemed to prove: 175 in March, 248 in April, 388 in May, 303 in June, 360 in July, and 373 in August. More strikes had taken place in 1917, but more workers had gone out in 1919’s climate of hysteria. This was also the summer of bloody attacks on African Americans who had come up from the South to jobs in northern industry. Antiblack pogroms made 1919 the Red Summer: red for bloodshed as well as labor conflict.

8