The History of White People (35 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

Thanks to medical advances that made sterilization relatively easy and safe, Indiana had led off the sterilization wave in 1907 with a law proclaiming, “WHEREAS, heredity plays a most important part in the transmission of crime, idiocy, and imbecility…”

17

*

Other states followed, but with mixed results, for involuntary sterilization remained controversial. The courts invalidated such laws on the basis of cruel and inhumane punishment, for lack of due process, and for failures in equal protection under the law. New Jersey’s state supreme court quickly struck down a compulsory sterilization law in 1913, and governors in Vermont, Nebraska, and Idaho vetoed others.

18

If sterilization were to prevail, expert guidance was called for. Undaunted, in 1922 Davenport’s Eugenics Record Office offered a model eugenical sterilization law meant to assist states in crafting involuntary sterilization laws that could withstand court challenge. In 1924 Virginia passed the first such act, stating that “heredity plays an important part in the transmission of insanity, idiocy, and imbecility, epilepsy, and crime.”

19

The court test that followed increased the visibility of “degenerate families” and, in light of the long-standing prejudice against poor white southerners, gave degeneracy a poor and female southern face.

T

HE FIRST

person slated for sterilization under Virginia’s sterilization law was eighteen-year-old Carrie Buck.

20

(See figure 19.1, Carrie Buck and her mother.) Buck had not been accused of a crime; she was described as a pregnant, unmarried, feebleminded daughter of an unmarried, feebleminded mother living in Virginia’s State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded. Prominent eugenicists entered the case against her to halt the propagation of “these people [who] belong to the shiftless, ignorant and worthless class of anti-social whites of the South.”

21

The U.S. Supreme Court upheld Virginia’s sterilization law 8–1, led by American law’s eminence grise, the eighty-one-year-old Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote the majority opinion. Holmes accepted Goddard’s argument that Buck’s weaknesses were hereditary. He also agreed with the prevailing logic that criminals were born, not made, and that society could protect itself by preventing their birth. Holmes decreed it “better for all the world, if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind.” His famous conclusion—“Three generations of imbeciles are enough”—echoed throughout American law.

22

The associate justices former president William Howard Taft and Louis D. Brandeis concurred. And so sterilization became settled law in many states, an acceptable means of dealing with people designated feebleminded—especially of poor women of all races bearing children out of wedlock.

23

Fig. 19.1. Carrie Buck and her mother, Emma Buck, at the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded, just before going to trial in 1924.

During the 1930s, following

Buck v. Bell

, local law enforcement and welfare officials rounded up the poor and sterilized them practically en masse: by 1968, some 65,000 Americans had been sterilized against their will, with California far in the lead and Virginia a distant second.

24

*

The American model eugenical sterilization law that had inspired Virginia’s 1924 law also worked in Germany. On gaining power in 1933, National Socialists quickly enacted a law for the prevention of progeny with hereditary diseases, which included deafness and blindness as well as mental handicap and chronic mental or physical illness. In Germany, as in the early twentieth-century United States, the prime targets of involuntary sterilization were poor people. Anglo-Saxon, Teutonic, or Nordic ancestry did not spare poor whites stigmatized as Jukes, Ishmaelites, Kallikaks, and Bucks.

As it turned out, Carrie Buck represents an all too common case of personal vulnerability. At about age eight, she had been placed in a foster home. Some years later a member of that family raped her. Pregnant as a result of the rape, she was sent to the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded to be sterilized as soon as she gave birth. Primitive, haphazardly administered Stanford-Binet intelligence tests rated her and her mother as imbeciles, but as an adult, Carrie showed no signs of impairment. Against a backdrop of degenerate-family studies demonizing poor white people, Carrie Buck’s sterilization had resulted from sexual abuse, not mental weakness.

25

Despite its promise of preventing social ills on the cheap, sterilization never attained total acceptance, for doubts over who should make such intimate decisions never subsided, and bias characterized their execution. Opponents’ arguments mounted: Catholics objected to this breach of the human body, socialists pointed to the class bias of eugenics, and anthropologists argued that culture, not biology, explained characteristics that sterilization was supposed to extinguish.

Eugenic sterilization ultimately fell out of favor, but the fall was slow and gradual. During the 1930s, when German National Socialists took it up, demonstrating the deadly and perverse workings out of eugenics, the field lost its standing as objective science. Civil rights protests in the 1960s and 1970s against the involuntary sterilization of black, American Indian, and Latina women effectively stripped the practice of respectability as public policy. Different morals demanded different policies. Virginia repealed its sterilization law in 1974, but Carrie Buck died in 1983, before her vindication. On the seventy-fifth anniversary of the

Buck v. Bell

decision, in 2002, the state placed a commemorative marker in her hometown of Charlottesville, and the governor issued a formal apology. Oregon, North Carolina, and South Carolina followed Virginia’s repudiation.

And here ends the compulsory sterilization story that began with degenerate-family research. Another story with shared roots unfolded at the same time, leading to the mental testing of immigrants and to immigration restriction.

M

ental tests: such a simple and accurate means of rating human intelligence, even, as Robert Yerkes, a leading tester claimed, of appraising “the value of a man.”

1

Once Henry H. Goddard had imported Alfred Binet and Theodore Simon’s mental tests into the United States, it became apparent that their usefulness reached far beyond their limited role in France. There, the tests designated schoolchildren for special education; in the United States, they rated the children at the Vineland school for the feebleminded and then went on to serve other, much wider purposes. Officials at Ellis Island figured Goddard’s tests in Vineland could help them decide who, among immigrants streaming into the country, could stay and who had to return.

What were these tests like? In 1917 masses of U.S. Army draftees who could read answered questions like these:

Why do soldiers wear wrist watches rather than pocket watches? Because

they keep better time.

they keep better time. they are harder to break.

they are harder to break. they are handier.

they are handier.

Glass insulators are used to fasten telegraph wires because

the glass keeps the pole from being burned.

the glass keeps the pole from being burned. the glass keeps the current from escaping.

the glass keeps the current from escaping. the glass is cheap and attractive.

the glass is cheap and attractive.

Why should we have Congressmen? Because

the people must be ruled.

the people must be ruled. it insures truly representative government.

it insures truly representative government. the people are too many to meet and make their laws.

the people are too many to meet and make their laws.

2

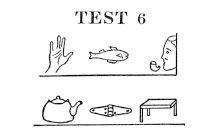

Men who could not read answered pictorial questions. Soldiers were to say what was missing from each picture:

3

*

(See figure 20.1, “Test 6.”)

Fig. 20.1. “Test 6,” in Carl C. Brigham,

A Study of American Intelligence

(1923).

Testers aimed high, promising to measure innate intelligence, not simply years of education or immersion in a particular cultural milieu. This claim was obviously absurd, but no matter. The allure of mental testing proved irresistible, because demand for ranking people was high, and the process was cheap and, best of all, apparently scientific. The juxtaposition of congressional mandates and the ambitions of early twentieth-century social scientists explains how Goddard went from degenerate families to intelligence testing of immigrants.

N

ATIVISTS HAD

long denigrated immigrants on the grounds of their supposed inferiority. Prescott Farnsworth Hall, one of the then recent Harvard graduates founding the Immigration Restriction League in 1894, mashed together degenerate families, immigrants, and competitive breeding: “The same arguments which induce us to segregate criminals and feebleminded and thus prevent their breeding apply to excluding from our borders individuals whose multiplying here is likely to lower the average of our people.”

4

This logic steadily gained ground.

From the 1890s onward, federal legislation toughened standards for excluding “lunatics,” “idiots,” people likely to become public charges, the insane, epileptics, beggars, anarchists, “imbeciles, feeble-minded and persons with physical or mental defects which might affect their ability to earn a living.”

5

But with five thousand immigrants passing through Ellis Island daily, sorting through them imposed an impossible task on ten or so Public Health Service physicians. Something had to be done. Learning of Goddard’s methods, the commissioner of immigration concluded that help lay at hand right there in New Jersey. He invited Goddard to use his newfangled intelligence tests to speed up the exclusion process, an assignment Goddard carried out with the help of his lady testers from Vineland.

6

*

Certain alarming conclusions leaped off the pages of Goddard’s report: