The History of White People (44 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

Ford and Lindbergh also had German honors in common. Both received the Grand Service Cross of the Supreme Order of the German Eagle, the highest honor to a distinguished foreigner, in 1938—Lindbergh in Germany, Ford in Detroit before an audience of fifteen hundred prominent citizens.

16

It was not until the pogrom of

Kristallnacht

in 1938 and the onset of ever more violent attacks on Jews in Germany and Austria that the tide truly turned, and it became more difficult to find anything good to say about the Nazis.

Once the United States entered the war that had resumed in 1939, Americans, led by President Franklin Roosevelt and his New Dealers, drew sharper contrasts between Nazi racism and American inclusion. They pointed out that whereas Germany and Japan, the country’s two prime enemies, based their national identities in race, the United States had become a nation of nations—Walt Whitman’s words in

Leaves of Grass

of 1855—a nation united in its diversity. This version of the society had been heard earlier in the twentieth century.

B

EFORE THE

hysteria associated with the First World War snuffed it out, a nascent and similar cultural pluralism had been taking shape. One early example was the

Menorah Journal

, a magazine created in 1915 by Jewish students at Harvard seeking a middle road between their religious and their national identities, between living as Jews and living as Americans. One of them, Horace M. Kallen (1882–1974), answered Edward A. Ross’s intemperate

The Old World in the New

(1914), first in two articles for the

Nation

in February 1915, then in a book,

Culture and Democracy in the United States: Studies in the Group Psychology of the American Peoples

(1924).

17

His repudiation of the purely Anglo-Saxon character of the United States came to be known as “cultural pluralism.”

*

Kallen chronicled wave after wave of European immigrants, beginning with the British, Irish, Germans, and Scandinavians, and continuing with others long denigrated as “new immigrants”: French Canadians, Italians, Slavs, Jews. They deserved to be integrated, whereas the Anglo-Saxon stock was highly overrated, whether in burnt-out New England or in the South, where “the native white stock, often degenerate and backward, prevail among the whites…[who] live among nine million negroes, whose own mode of living tends, by its mere massiveness [to contaminate the whites].”

18

Note that non-Europeans do not figure as immigrants or as constituents of Kallen’s ideal America.

Confusingly, nor do the children of European immigrants come off very well. Kallen belonged to the numerous throng of would-be friends of the immigrant who looked askance at their American-born children. The second generation, he regretted, “devotes itself feverishly to the attainment of similarity [to Anglo-Saxons]. The older social tradition is lost by attrition or thrown off for advantage.” Crime and vice appeal as routes to wealth and shallow amusement.

19

Better they should return to the picturesque immigrant ways of their parents. So much for a melting pot.

Rather than proposing, à la Henry Ford, an Americanizing melting pot, in which immigrant “ethnic types” would melt into ersatz Anglo-Saxons or be forced to leave the United States, Kallen envisioned American culture as “a great and truly democratic commonwealth,” as “an orchestration of mankind. As in an orchestra, every type of instrument has its specific timbre and tonality, founded in its substance and form; as every type has its appropriate theme and melody in the whole symphony, so in society each ethnic group is the natural instrument, its spirit and culture are its theme and melody, and the harmony and dissonances and discords of them all make the symphony of civilization.”

20

But Kallen’s was a symphony of purely European civilization.

The progressive intellectuals Randolph Bourne and John Dewey quickly echoed Kallen’s preference for ethnic color in 1916 and 1917. Bourne welcomed “our aliens” into American culture as equal partners with the Anglo-Saxon, heralding a new United States: “we have all unawares been building up the first international nation…. America is already the world-federation in miniature…the peaceful living side by side.” Dewey admitted, “[T]he theory of the Melting Pot always gave me rather a pang,” because he disliked the idea of “a uniform and unchanging product.” Speaking to Jewish college students, Dewey much appreciates difference, and is willing to support the cause of Zionism.

21

These sentiments had been a promising start, but such welcoming words largely went silent during the 1920s. Then, in the 1930s, a defender of the immigrants’ American children appeared in popular culture.

L

OUIS

A

DAMIC

(1898 or 1899–1951) was born in Blato, Slovenia, then an Austrian possession.

*

After his prosperous peasant parents sent him to high school, he immigrated to the United States in 1913, a self-described “young Bohunk.” Settling in New York City, Adamic did unskilled labor in the offices of the

Narodni Glas

, a Slovenian-language newspaper, one of thousands of institutions immigrants had created to serve their communities. Ambitious and hardworking, he began translating articles from the

New York World

into Slovenian, then graduated to writing about Slovenians in America. When

Narodni Glas

folded in 1916, a victim of the persecution of foreign-language periodicals during the First World War, Adamic joined the Army, where he gained U.S. citizenship. Demobilized in 1923 in San Pedro, California, the port of Los Angeles, he spent the next six years there, working and writing colorfully about himself and the Croatian workers in San Pedro.

22

These articles so charmed California literati, notably Cary McWilliams, Mary Austin, and Upton Sinclair, that they eased Adamic’s approach to H. L. Mencken, who in 1928 began publishing the first of eight of Adamic’s articles in the

American Mercury

, the most fashionable literary magazine of the 1920s.

23

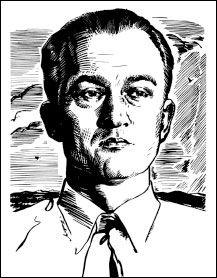

(See figure 25.1, Louis Adamic.)

After relocating to New York City in 1929, Adamic began to publish at a furious rate. His first real book,

Dynamite: The Story of Class Violence in America

, appeared in 1931 to favorable reviews and a boost from the Nobel prize–winning novelist Sinclair Lewis.

24

†

Dynamite

signaled Adamic’s abiding sympathy for workers, which soon made him a supporter of the CIO, the great industrial labor federation born of the New Deal. His 1932 autobiography,

Laughing in the Jungle

, a series of satirical sketches, also well received, earned him a prestigious Guggenheim literary fellowship in 1932.

As a Guggenheim Fellow, Adamic was able to visit his former home—part of Yugoslavia since the end of the First World War—for the first time since leaving it nearly two decades earlier, bringing along his non-Slav American wife, Stella. In Split, Dalmatia, Adamic met Ivo (John) F. Lupis-Vukich, formerly publisher of a foreign-language newspaper in Chicago, who lectured Adamic on the importance of second-generation immigrants in the United States, the “strangers” most Americans did not understand. Adamic took this idea to heart.

25

Fig. 25.1. Louis Adamic on his book tour, 1934.

A chronicle of his stay in Yugoslavia,

The Native’s Return

(1934) became a Book-of-the-Month Club main selection, quickly sold fifty thousand books, and remained a best seller for nearly two years. It brought Adamic twenty or more letters a day from Slavs living in the United States. In the course of promoting his book in heavily Slav industrial centers, Adamic delivered his “Ellis Island and Plymouth Rock” lecture hundreds of times, becoming the prime spokesman for immigrants and their children. His response to the crowds and to yet another nativist editorial by George Horace Lorimer of the

Saturday Evening Post

coalesced into “Thirty Million New Americans” in

Harper’s Magazine

in November 1934. Despite its patronizing tone, this piece quickly became a classic statement of 1930s cultural pluralism.

“Thirty Million New Americans” and Adamic’s subsequent books and articles sought to recast the fundamental identity of Americans. His main points were simple: the U.S. population is diverse, not essentially Anglo-Saxon, and immigrants are full-fledged Americans. As he said often, Ellis Island deserves a place at the center of American origins, right next to Plymouth Rock. As the product of so many regions and cultures, the children of immigrants carried a vast potential to “enrich the civilization and deepen the culture in this New World.”

26

In many ways Adamic unwittingly picked up themes from the nineteenth and very early twentieth centuries. His view of immigrants even shared a point with Ralph Waldo Emerson. Whereas Emerson had blithely consigned these “guano races” to faceless hard work, death, then service to the greater American good as mere fertilizer, Adamic paused lovingly with immigrant workers while they survived. He gave them names, such as Peter Molek, and listened to their wisdom. Broken after decades of dangerous work in American mines and steel mills, they recognized their alternating role as both builders of American progress and—their own word—“dung.”

“The Bohunks indeed were ‘dung,’” Adamic agrees in his autobiography, but he loved “their natural health, virility, and ability to laugh” and the way they saw themselves as working-class in their adopted country. A Slav without formal education, like the fictional Molek, would see injustice where “millionaires who wore diamonds in their teeth and had bands playing while they bathed in champagne.” Living in miserable slums, impoverished immigrant laborers recognized that the fundamental flaw of American society lay in the maldistribution of wealth.

27

In fact, ambivalence dominated Adamic’s attitude toward his immigrant peers. Though Kallen was writing two decades earlier from Harvard, and Adamic focused on working-class neighborhoods in Pennsylvania and the industrial Midwest, both authors depict American-born children of immigrants somewhat unfavorably.

*

As Adamic describes them, most in the second generation are ashamed of their parents and filled with feelings of inferiority, rendering them “invariably hollow, absurd, objectionable persons,” whose “limp handshakes” give him the “creeps.”

28

In time they may contribute to society, but at the moment they constitute a problem, and here Adamic’s ambivalence emerges full-blown. The children of immigrants present “one of the greatest and most basic problems in this country; in some respects, greater and more basic [than] the problem of unemployment, and almost as urgent.” They are a “problem” thirteen times in the article’s eleven pages, on account of their “feelings of inferiority” (sixteen times). Their “racial” identities (ten times) separated them from “old [Anglo-Saxon] stock” Americans (nine times). Even their champion was using the language of races to paint a dismal picture.

But while Adamic might join Kallen in the language of race in 1934, he departs from him in two important ways: Adamic usually links race to culture, as if to hedge his bets on permanence. Members of his second generation are distinctive by “race and culture,” whereas for Kallen a generation earlier, race was the same thing as culture. Adamic glimpses the possibility of change in the thirty million new Americans, for he notes the ability of a few young people to become attractive and successful. They simply need encouragement to become full-fledged Americans.

E

NCOURAGEMENT CAME

from several quarters, notably from a New Jersey Quaker, Rachel Davis DuBois (1892–1993), a Woodbury high school teacher inspired by W. E. B. Du Bois and angered by Father Charles Coughlin’s broadcast anti-Semitism. DuBois pioneered what was called “intercultural education” by establishing the (nongovernmental) Service Bureau for Intercultural Education in 1934 to help other teachers reach out to their second-and third-generation immigrant students and incorporate information about them in their curricula—multiculturalism

avant la lettre

.

29

*

As she approached the federal government and radio broadcasters with a plan to counter derogatory images of alien races, Adamic was one of her supporters.

*