The History of Florida (29 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

on Spain on 9 January 1719. Two days previously, the Company of the In-

dies had ordered the Sieur de Bienville, the governor of Louisiana, to take

possession of Pensacola. On 14 May, the French captured the recently built

battery on Point Sigüenza, then crossed the channel to Fort San Carlos de

Austria and engaged in a brief cannonade with the fort. Governor Juan Pe-

dro Matamoros de Isla, unaware that France and Spain were at war, quickly

surrendered.

The French took their Spanish prisoners to Cuba, where they planned

to leave them. But when they reached Havana, its commander, Captain

General Gregorio Guazo Calderón, refused to recognize the French flag

of truce on the grounds that the French had attacked Pensacola without

proper warning. The Spaniards prepared to recapture Pensacola, and Admi-

ral Alfonso Carrascosa de la Torre, commander of a Spanish fleet of twelve

ships and 1,800 men, reached Pensacola on 6 August. When the Spaniards

landed, about ninety French soldiers (the numbers vary) deserted to join

Pensacola, 1686–1763 · 135

them. The French officer in charge at the site, the Sieur de Châteaugué, Bien-

ville’s brother, still had about 200 soldiers under his command, but they put

up such a feeble defense he had no choice but to surrender. The Frenchmen

were sent to Cuba for imprisonment in Havana’s notorious Moro Castle.

When word reached Mobile that the Spanish fleet was at Pensacola,

French troops accompanied by several bands of Indians rushed there but

arrived too late. The Chevalier de Noyan, who commanded one of the

French-Indian forces, talked with Matamoros de Isla and learned that the

next Spanish objective was Mobile and Dauphin Island. Noyan quickly re-

turned to Mobile, and the French prepared to defend the area.

Part of the Spanish fleet led by Captain Antonio de Mendieta quickly set

sail for Dauphin Island. After twelve days and nights of frustrating efforts

to capture Dauphin Island, and without the arrival of expected assistance

from México, the Spaniards final y gave up and departed Mobile Bay on 25

August.

In early September, the French made plans to recapture Pensacola. Bien-

ville led a force of 400 Indians overland, while the recently arrived French

fleet under the command of Admiral Desnos de Champeslin left Mobile and

reached Pensacola on the sixteenth. Pensacola was well defended because

the Spanish

flota

from Havana was still there, but the naval battle that en-

proof

sued lasted only an hour before the Spaniards gave up. The reinforced Span-

ish battery at Point Sigüenza put up a stout defense but ran out of ammuni-

tion and surrendered. Matamoros de Isla at Fort San Carlos de Austria had

planned a strong defense, but fear of Bienville’s Indian warriors persuaded

him to give up without a fight.

The French sent 625 privateersmen and noncombatants back to Havana

in exchange for the French soldiers under Châteaugué. The soldiers and the

officers, including Matamoros de Isla, were taken as prisoners to Brest, in

France. When the Spaniards departed, the French permitted the Indians

to plunder the Spanish presidio. Forty-seven of the Frenchmen who had

surrendered to the Spaniards in August were court-martialed. Twelve were

hung, the others were sentenced to forced labor. Twelve French soldiers and

eight Indians were left at Pensacola under the command of the Sieur Delisle

with orders to give token opposition if the Spaniards returned. He was then

to destroy what was left of the fort and retreat to Mobile.

A long-awaited Spanish fleet from Veracruz, commanded by Admiral

Francisco de Cornejo, final y sailed for Pensacola but went instead to St.

Joseph’s Bay. There Cornejo was warned that Champeslin and his ships were

still at Pensacola. Fearful that he might not succeed in an attack upon the

136 · William S. Coker

French, Cornejo went to Havana to await reinforcements. Plans to recapture

Pensacola continued, but nothing was actual y done. By early 1720, peace

overtures were under way in Europe.

France planned to keep Pensacola under any circumstances, while Spain

demanded its return. For nearly a year they negotiated an end to the war.

Final y, France recognized that it would be impossible to obtain Spanish

cooperation unless Pensacola was restored to Spain, so, in the treaty of 27

March 1721, France gave up its claim.

Bienvil e received orders on 6 April 1722 to return Pensacola to Spain.

Lieutenant Colonel Alejandro Wauchope, the Spanish governor-to-be of the

Pensacola presidio, visited Mobile in June. He carried instructions for the

French to return Pensacola and all of the armament and supplies that were

there in 1719, but Bienvil e could not comply with the Spanish demands:

The Indians had destroyed virtual y everything in the presidio except some

cannon, which were buried in the sand.

After some delay, Wauchope reached Pensacola with three ships and an

infantry company. Wauchope (also written Wauchop) was a Scotsman who

had served in Spain’s Irish Brigade. He received possession of the site from

Lieutenant Jean Baptiste Rebue (also Reboul) on 26 November. All that re-

mained was one dilapidated cabin, a bake oven, and a lidless cistern.

proof

Wauchope’s orders cal ed for a canal to be dug across Santa Rosa Island to

lower the water level in Pensacola Bay to prevent large enemy ships of war

from entering the harbor. An engineer, Don José de Berbegal, accompanied

Wauchope to supervise the project. If it proved to be an impractical plan,

they were to move the presidio to Santa Rosa Island. The projected fort to

be built on Point Sigüenza was to be manned by 150 soldiers of infantry

and artillery but supplemented by the garrison from St. Joseph. In February

1723, Captain Pedro Primo de Rivera and men from St. Joseph’s Bay were

brought to Pensacola. By that date considerable progress had been made

in building the new Presidio Isla de Santa Rosa/Punta de Sigüenza about

three-quarters of a mile east of Point Sigüenza. The canal across the island

was not attempted.

The new presidio consisted of a church, warehouse, powder magazine,

quarters for the officers, barracks for the soldiers, twenty-four small build-

ings for the workmen, convicts, and others, a bake oven, a house for the

governor, and a look-out tower sixty feet high.

But for the Spaniards, troubles in Pensacola were far from over. Wau-

chope had the same basic problem that his predecessors confronted: Sup-

plies for the garrison were uniformly inadequate and late in arriving. Once

Pensacola, 1686–1763 · 137

more, Pensacola turned to its French neighbors for help. Bienville complied

with Wauchope’s plea for assistance and sent supplies from New Orleans to

Pensacola via Mobile. In spite of this help, Wauchope intended to observe

royal orders that directed that all contraband French goods arriving for sale

at Pensacola were to be burned and those involved punished.

In 1724, Wauchope complied strictly with these orders when a Madame

Olivier and others from Mobile visited Pensacola. The madame, it seems,

came to visit friends, while her companions brought some goods to sel . The

Spaniards seized and burned the boats including the merchandise and put

all the Frenchmen except Madame Olivier and her daughter in irons. This

was only one of several similar incidents.

If contraband trade was not enough, hostile Indians presented the Span-

iards with additional trouble. An attack upon Pensacola by the pro-English

Talapoosa in 1727 may well have spelled disaster for the Spaniards had it not

been for the Sieur de Perier, governor of Louisiana, who came to the rescue.

He warned the Talapoosa that, if they did not cease their attack upon the

Spanish presidio, he would turn loose a large force of Choctaw that would

destroy them. As a result, the Talapoosa lifted the siege and retreated from

Pensacola.

Illegal trade between the French and Spaniards could not be prevented,

proof

despite the best efforts of officers like Wauchope. In 1738, the Spanish sec-

retary of state wrote the viceroy of New Spain that he should take action

against the commandant and officers at Pensacola unless they stopped trad-

ing with the French. Such warnings had little effect, but one policy did affect

this trade. In 1743, Louisiana officials forbade French merchants at Mobile

and New Orleans to carry merchandise to Pensacola because the Spaniards

had not paid their outstanding debts. The Spaniards were thus forced to go

to New Orleans for their goods and to pay cash for them.

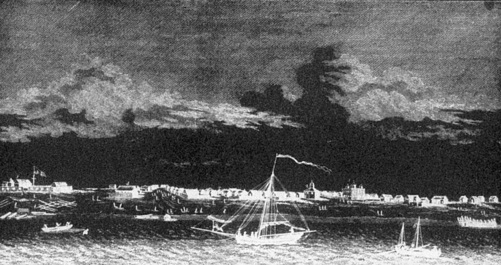

The year 1743 was important to Pensacola for reasons other than the trade

imbroglio. An artist’s sketch of the Santa Rosa Island presidio and orders

for a report on the remote outpost would be significant in the history of

Pensacola.

Dominic Serres, a Frenchman serving on a trading ship that visited Pen-

sacola in 1743, made the sketch of the presidio. He later became a seascape

painter in London. When the British learned that Florida was to be traded

to Great Britain in 1763, Serres’s drawing was published in William Roberts’s

Natural

History

of

Florida

(London, 1763). Several of the buildings are iden-

tified in the sketch, including the octagonal-shaped church. This drawing is

the only existing representation of the island presidio.

138 · William S. Coker

On 15 April, the viceroy in Mexico City directed Field Marshal Pedro de

Rivera y Vil alón to prepare a report on the Pensacola presidio. Rivera had

made an extended inspection of the presidios west of Louisiana some years

earlier, which had had a strong impact on those fortifications.

In the preparation of his Pensacola study he did not visit the site but

relied for his observations on the letters and recommendations of men who

had served there. In his report, dated 29 May 1744, Rivera briefly, and with

some errors, traced the history of Pensacola’s presidios and the ebb and

flow of the three-way struggle for Florida among France, Great Britain, and

Spain. He noted that the violent storms that had virtual y destroyed the pre-

sidio on several occasions were an ever-present danger. He also recognized

that, in the event of war, the presidio would easily fall prey to an attacking

force but that it would cost thousands of pesos to build a more suitable

fort, which would then require more manpower. In spite of its problems,

Rivera recommended retaining Pensacola but with a reduction in the size

of the garrison. He did not have a recommendation on whether the presidio

should remain on the island or be moved back to the mainland.

The only part of Rivera’s report that seems to have been implemented

was the reduction in manpower. In 1750, two companies of infantry were

stationed there, only sixty-two men with thirty-six fit for duty. The labor

proof

battalion had twenty-four men.

Sometime in the 1740s the Spaniards built a smal blockhouse on the

mainland which they named Fort San Miguel. Its purpose and that of

the smal detachment of soldiers stationed there was to help protect the

Yamasee-Apalachino Indians living nearby from attacks by British-al ied

Indians. Located in present-day downtown Pensacola, the little fort was

soon to be the site of Pensacola’s third presidio.

On 3 November 1752, a hurricane struck Santa Rosa Island. It destroyed

all of the buildings except a storehouse and the hospital. Nearly three years

later, a fort built of stakes, a warehouse for supplies, and another for gun-

powder were located on the site of the old presidio. Some distance to the

west were the church, hospital, commandant’s quarters, and a camp for the

garrison. In August 1755, the buildings were reported to be deteriorating.

The following summer, the Marqués de las Amaril as, the viceroy of New

Spain, ordered that the presidio be relocated to the site of Fort San Miguel

on the mainland and that it be named the Presidio San Miguel de las Ama-

ril as. A royal order of October 1757 changed the name to the Presidio San

Miguel de Panzacola. Although the area had long been familiarly known as

Panzacola, it was now official y so recognized. The new presidio was to be