The History of Florida (32 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

British Rule in the Floridas · 149

Johnstone’s reputation as a combative and ill-tempered man, he extended

suffrage to leaseholders and landowners alike and authorized elections to a

colonial assembly for West Florida in 1766. In striking contrast, a colonial

assembly in East Florida was not seated until 1781.

The major chal enge for both Grant and Johnstone was attracting set-

tlers. Grant characterized East Florida as a “New World in a State of Nature

when I landed in Augustine 1764. Not an acre of land planted in this country

and nobody to work or at work.” He was alarmed, however, when he dis-

covered “straggling woodsmen” settling on rural lands without acquiring

land titles. Farmers and laborers were desperately needed, but Grant was

determined to prevent the American frontiersmen he contemptuously re-

ferred to as “crackers” from settling in his province. Like Grant, Governor

Johnstone wanted a ban on the frontiersmen who wandered through the

province without establishing permanent settlements and whom Johnstone

called “the refuse of the Jails of great Citys, and the overflowing scum of the

empire.” Johnstone’s goal was to recruit French, German, and Swiss immi-

grants, and to coax residents of New Orleans to cross the border and settle

in West Florida.

Both governors were hindered by policies that awarded 10,000- and

20,000-acre tracts to men of wealth and influence in Britain who had no

proof

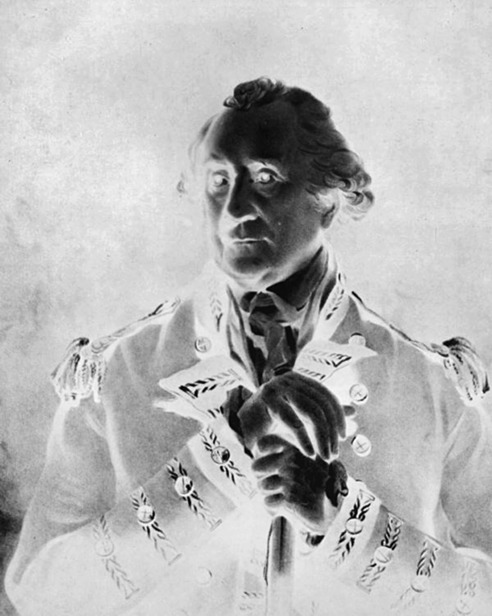

Portrait of George Johnstone, the first

James Grant, the first governor of

governor of British West Florida. Courtesy

British East Florida. Portrait courtesy

of the State Archives of Florida,

Florida

of the National Galleries of Scotland,

Memory

, http://floridamemory.com/items/

and Lady Clare and Sir Oliver Russell,

show/19984.

Ballindalloch, Scotland.

150 · Robin F. A. Fabel and Daniel L. Schafer

intention of establishing settlements. Grant warned that absentee landlords

would claim the best land and let it sit idle to speculate on rising prices rather

than send settlers to develop their tracts. “No Lands ought to be granted,

but to People who are actual y to reside in the Colony,” Grant reasoned,

but his advice was not heeded. Recognizing the inevitable, Grant urged the

“great grantees” to send settlers and to invest in the development of their

tracts. He wrote repeatedly to the grantees in Britain urging them to employ

enslaved black men and women rather than white Europeans, who became

debilitated by the heat in Florida and abandoned the rural settlements for

the colonial towns. Even the often praised German immigrants “won’t do

here. Upon their landing they are immediately seized with the pride which

every man is possessed of who wears a white face in America and they say

they won’t be slaves and so they make their escape.” He told one grantee: “no

produce will answer the expense of white labor,” and another: “Settlements

in this warm climate must be formed by Negroes.”

Governor Grant promised government office support and free land to

entice South Carolina and Georgia planters to migrate to East Florida and

bring with them their experienced slave laborers. In addition, Grant at-

tempted to “put a spur” to proprietors by developing one of his own rural

tracts, called Grant’s Vil a, as a model indigo plantation. When the proceeds

proof

of four years of profits from indigo exports repaid all of Grant’s startup ex-

penses, including the cost of seventy-eight slaves, planters paid attention.

Soon after, nearly all of the field laborers in East Florida were enslaved black

men and women.

Numerous St. Augustine residents acquired farms west of the town to-

ward the St. Johns River, and to the north alongside the North, Guana, and

Pablo Rivers. George Grassel , a carpenter in the town, owned four farms.

Englishman Spencer Mann ran a mercantile business in St. Augustine from

1764 to 1784, while his overseer and sixty slaves cultivated rice, indigo, and

corn, and harvested lumber, shingles, and naval stores at nine rural proper-

ties. Francis Philip Fatio and Francis Levett had houses in St. Augustine plus

estates of ten thousand acres west of St. Augustine on the St. Johns River.

James Penman came to East Florida in 1767 as the agent for the planting

fortunes of absentee owner Peter Taylor at a 10,000-acre estate at today’s

Daytona Beach. Penman soon became a leading St. Augustine merchant,

and the owner of six rural estates and 188 black slaves. Several other large

estates were developed south of St. Augustine by Lt. Governor John Moult-

rie, Captain Robert Bissett, London merchant Wil iam El iot, and others,

al worked by enslaved Africans. The wealthy London merchant Richard

British Rule in the Floridas · 151

Oswald shipped Africans from Bance Island, Sierra Leone, to Mount Os-

wald, a 20,000-acre plantation at today’s Ormond Beach where 240 enslaved

men and women were domiciled.

The major exception to Governor Grant’s proviso that Florida settle-

ments “must be formed by Negroes” was Dr. Andrew Turnbul ’s Smyrnea

settlement located south of St. Augustine at Mosquito Inlet (present-day

New Smyrna Beach and Edgewater). More than one hundred slaves were

purchased for work at Smyrnea, but indentured Europeans became the

mainstay of the labor force. Turnbul , a Scotland-born physician who re-

sided for years at Smyrna, Turkey, while employed by the Levant Company,

partnered with William Duncan, a baronet and physician to King George

III, and Prime Minister George Grenvil e to develop three 20,000-acre

tracts of land with the labor of indentured Europeans. Turnbul traveled

to the Mediterranean to recruit 1,400 Greek, Italian, and Minorcan inden-

tures. The scale of development envisioned for Smyrnea exceeded anything

attempted elsewhere in the North American colonies, but the agonizingly

high sickness and mortality rates, food and funding shortages, labor unrest,

rebellion, and charges of brutal treatment led to the col apse of the settle-

ment in 1777 and 1778. Those who survived the high disease and death rates

and the sometimes oppressive labor conditions abandoned Smyrnea and

proof

settled in what became known as the “Minorcan Quarter” of St. Augustine.

They rented vacant farmland near the town walls, became fishermen, la-

borers, and merchants, and distinguished themselves as enduring pioneer

families whose descendants are still prominent Florida citizens.

At West Florida, migrants began arriving soon after accession, but in-

fertile soil near Pensacola and high sickness and mortality rates slowed the

inflow. Settlement of the Natchez region along the Mississippi River, where

some of the finest agricultural land in North America could be found, was

frustratingly slow. This was in part the result of the decision in 1768 by the

War Office in London to withdraw the garrisons from the frontier outposts

at Manchac and Natchez. The only significant products exported in the

province’s first decade were the deerskins, beaver pelts, and furs shipped

out of Mobile.

By the early 1770s, however, news of the abundant fertile soil along the

western rivers had spread to Britain’s other North American colonies and

prompted a rush of emigrants to set out for West Florida. The Company

of Military Adventurers, led by General Phineas Lyman of Connecticut

and joined by dozens of veterans of the Seven Years’ War, had formulated

plans to settle New Englanders on the Mississippi River as early as 1763. At

152 · Robin F. A. Fabel and Daniel L. Schafer

a meeting of the Adventurers at Hartford in June of that year, dues were

collected and General Lyman was elected to represent them in London to

lobby for a massive land grant, possibly even a separate province. Lyman un-

wisely chose to transform his assignment into a nine-year sojourn while he

sought a personal grant of 20,000 acres and chased after an aristocratic title.

Lyman’s personal ambitions delayed the project unnecessarily and greatly

diminished the actual number of settlers who eventual y traveled to West

Florida to claim land.

In addition to problems recruiting settlers, both governors faced chal-

lenges as they negotiated land concessions and trade agreements with Na-

tive Americans. It was Grant’s conviction that migrants needed to know they

could settle safely on rural Florida plantations, and that Native Americans

should feel confident that British rule would be just and generous. Grant

learned early that the Creek and the Seminole were “very tenacious of their

lands” and unlikely to make concessions if doing so would diminish their

annual harvests of deer- and bearskins. To avoid conflict, Grant imposed

strict rules on British fur traders and informed British planters that Creek

hunters had the right to pass through British farms in pursuit of game.

In November 1765, Grant convened a congress with fifty headmen of the

Lower Creek and the Seminole at Fort Picolata, located twenty miles west

proof

of St. Augustine on the St. Johns River. With the crucial assistance of John

Stuart, superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Department, a

treaty was arranged that resulted in a land concession that permitted the

British to occupy the land lying between the St. Johns River and the At-

lantic Ocean, and to the west and south as far as the tidal waters flowed.

Grant entertained lavishly and distributed gifts generously on this occasion,

and again in November 1767 when another congress was convened at Fort

Picolata. After the congress, Grant informed the Board of Trade that he

had countered suspicion with generosity by “load[ing] those Indians who

attended the Congress with presents, I fed them plentiful y, and gave them

as much provisions as they could carry away with them.” The congress had

been expensive, but the governor believed “money could not be better ap-

plied, as it certainly prevented an Indian War.” Similar meetings were held

in the remaining years of Britain’s brief tenure in Florida.

Governor Johnstone’s problems were more severe because of a greater

population imbalance, and also because of British policies that pitted one

Native American nation against another. This policy was most evident in

the continuing warfare between the Creek and the Choctaw. Johnstone pos-

sessed a stubborn and truculent nature and advocated a bel icose policy

British Rule in the Floridas · 153

Portrait of Patrick

Tonyn, the second

governor of British

East Florida. An early

absentee planter in

East Florida, Tonyn was

appointed governor

in 1774 and efficiently

organized the militia

and the defense of

the colony during the

American War of Inde-

pendence. Courtesy

of the State Archives

of Florida,

Florida

Memory

, http://flori-

damemory.com/items/

show/128483.

proof

toward his Native American neighbors. In an effort to promote cordial rela-

tions, Superintendent Stuart encouraged Johnstone to join him in a meeting

with tribal leaders to distribute gifts and negotiate differences. Johnstone’s