The History of Florida (28 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

rected that Pensacola Bay be occupied and fortified without delay. The ini-

tial force was to come from México, but because of a lack of troops and

money in México, and the fact that Spain was involved in King William’s

War (1689–97), nothing was done. There matters rested until 1698.

In that year, two events pushed the Spaniards to occupy Pensacola Bay.

Reports indicated that a French expedition led by the Sieur d’Iberville was

preparing to sail for Pensacola Bay. The French had been spurred to ac-

tion by the plans of Dr. Daniel Coxe of London, who hoped to establish a

large settlement of exiled French Huguenots in his province of Carolana

130 · William S. Coker

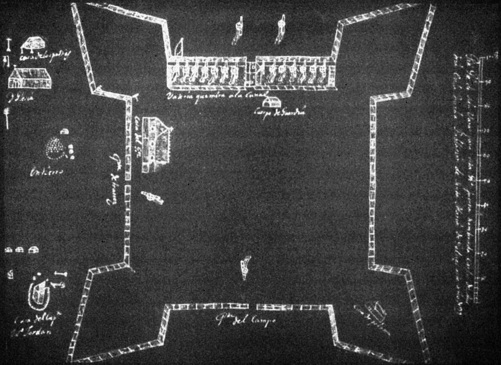

The village of Santa María de Galve, 1698–1722, is shown to the left side of Fort San

Carlos de Austria. From top to bottom at left are the rectory, church, cemetery, seven

cabins, and the residence of Captain Juan Jordán [de Reina]. The governor’s residence

was inside the fort. The first-known European settlement on the Barrancas coloradas,

proof

or Red Cliffs, the village and fort were captured by the French from Mobile and Dau-

phin Island in 1719 and then abandoned after the Spaniards returned to the site in 1722.

Electing to move to Santa Rosa Island, the Spaniards would not occupy the cliffs again

until the 1790s.

(Florida). The Gulf of Mexico was his objective. Spain ordered the viceroy

in México to occupy Pensacola Bay without delay. Captain Jordán de Reina,

who was in Spain at the time, left immediately for Havana to secure the

necessary troops and supplies and sail for Pensacola Bay.

Jordán de Reina reached Pensacola Bay on 17 November 1698 with two

ships and sixty soldiers. Four days later, Andrés de Arriola, the appointed

governor, who had visited Pensacola Bay in 1695, arrived from Veracruz

with three ships and 357 persons. Captain Jaime Franck, an Austrian, was

the military engineer. Franck selected a site for the fort near the Barranca

de Santo Tomé, which overlooked the entrance to the harbor, and began

to build. He named the fort San Carlos de Austria, for thirteen-year-old

Charles of Austria, later Charles VI of the Holy Roman Empire. Built of

pine logs, each side of the planned fort measured 275 feet with a bastion on

each corner. Immediate construction was restricted to building the front

Pensacola, 1686–1763 · 131

wal facing the harbor entrance, and there sixteen cannon were mounted

to discourage any foreign ships from entering the bay. Neither Arriola nor

Franck liked Pensacola, and both wanted to leave as soon as possible.

The situation at Pensacola was far from good. Many of the troops and

workers had been released from jails in México and were not desirable set-

tlers. Forty of the criminals deserted soon after their arrival, but most were

recaptured. The camp split into factions, and stealing was common. On 4

January 1699, a fire caused by some careless gamblers destroyed a number

of buildings, including the main storehouse for provisions, and the garrison

there faced the possibility of starvation.

To add to the Spaniards’ woes, the anticipated French squadron arrived

on 26 January. The commander of the fleet, the marquis de Chasteaumor-

ant, informed Arriola that they were only in search of some Canadian ad-

venturers. But Arriola was not deceived; he was sure that it was d’Iberville’s

expedition and that it intended to establish a base on the Gulf Coast. Arriola

refused permission to enter the harbor, and the French sailed westward.

Soon after they departed, Arriola left for México to warn the viceroy about

the French and to secure supplies and reinforcements.

Upon arriving at Veracruz, Arriola learned that because the Scots were

planning a colony at Darién (Panama) and the Spaniards were preparing

proof

A plan of the Pensacola Bay region in the period 1698–1763 showing the various presi-

dios. Drawn by Joe Gaspard.

132 · William S. Coker

an expedition to oust them, no help could be provided him. Reports also

reached México that Englishmen were planning a settlement near Pen-

sacola. Fortunately, the Scottish threat was soon over, and Arriola final y

secured 100 men from Mexican slums and prisons whom he carried to Pen-

sacola to assist him in driving both the French and English from the Gulf

Coast.

Arriola departed Pensacola on 4 March 1700 to accomplish his mission.

The so-called Englishmen turned out to be Frenchmen whom Arriola cap-

tured and carried to the French at Fort Maurepas (Ocean Springs, Missis-

sippi). The Spaniards were received with great hospitality. Arriola warned,

however, that the French fort was in Spanish territory and must be aban-

doned. The French countered that they had been ordered by their king to

establish the fort on the Gulf Coast to prevent the English from doing so

and that they could not leave without orders from France. Arriola decided

to give up his plans to oust the French and sailed for Pensacola. A hurricane

hit en route, and the Spaniards lost all their ships but one. After much suf-

fering, the survivors returned to Fort Maurepas, where, again, they were

well treated by the French, who returned them to Pensacola.

The Pensacola garrison suffered constantly from a lack of supplies. Ef-

forts to grow foodstuffs failed in the sandy soil. The garrison engaged in

proof

raising sheep and, much later, cattle. An abundant supply of large pine trees

enabled them to produce ships’ masts for export, but that industry never

made Pensacola self-sufficient and the settlement was forced to rely heavily

upon outside sources for its survival.

France and Spain had a basic difference in their reasons for being on the

northern Gulf Coast. The Spaniards came to prevent the French from set-

tling there. The French came to make money through trade with the Indians

and Spaniards. They mistakenly thought they were near the silver mines of

northern México, but they also hoped to discover rich mineral deposits in

the Mississippi Valley. The one aim Spain and France had in common was

to prevent the English from settling on the Gulf Coast.

When the French sold goods at Pensacola, they usual y received cash

because the Spaniards were most often paid in specie when the situado,

or annual subsidy, was received. Unfortunately, it did not always arrive on

time, and even when it did, it usual y contained only a fraction of the money

due the presidio.

The relationship between Spain and France over their Gulf Coast settle-

ments during the early years reflected their differing goals. In 1701, France

requested that Spain cede Pensacola to them. In turn, Spain wanted French

Pensacola, 1686–1763 · 133

Louisiana to be placed under the jurisdiction of the viceroy of New Spain.

Neither side succeeded in these diplomatic efforts, although the French con-

tinued to want Pensacola. Later, they argued over the boundary between

Florida and Louisiana: The Spaniards claimed jurisdiction to the east bank

of Mobile Bay, while the French held out for the Perdido River and Bay as

the boundary. This dispute went on for years, but Spain final y, and not will-

ingly, recognized the Perdido as the boundary.

The death of Carlos II on 1 November 1700 soon brought on the War of

the Spanish Succession (Queen Anne’s War in the colonies). Carlos II had

no children. Before he died, and after much diplomatic maneuvering, he

had designated Philip of Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV, as his heir. Other

European countries including England, not wanting to see France and Spain

united under one crown, formed the Grand Alliance, which declared war

on 4 May 1702. These events were to have a direct bearing on Spanish Pen-

sacola and on Mobile, where by 1702 the French had built Fort St. Louis de

La Mobile at the mouth of the Dog River. The French at Mobile were much

better supplied than were the Spaniards, and, fortunately for the Spaniards,

they were generous with what they had. The Spanish garrison would have

been forced to abandon Pensacola, or to surrender it to the English, if it had

not been for supplies and military support furnished by the French.

proof

After their military success in the Apalachee area in 1704, the English

and their Indian allies tried several times—unsuccessful y—to capture the

Pensacola presidio. They destroyed the fort in the winter of 1704–5, but the

French came to the Spaniards’ rescue. Between 1707 and 1713, the Anglo-

allied Indians, usual y led by a few Englishmen, laid siege to Pensacola on

several occasions, but help from Mobile forced them to retire. Almost mi-

raculously, the war ended with Pensacola still in Spanish hands.

Some but not much information is available on the priests who served

the presidio during its early years. Three priests arrived with Arriola in 1698:

Fathers Rodrigo de la Barreda, Alfonso Ximénez de Cisneros, and Miguel

Gómez Alvarez. In 1702, Arriola purchased a house from one of the soldiers

and converted it into a hospital, Nuestra Señora de las Angustias (Our Lady

of Afflictions). Fray Joseph de Salazar, a friar-surgeon, served in this hospi-

tal as did several others of the Order of San Juan de Dios. About 1709, the

hospital moved inside the fort; and Fray Juan de Chavarria and Fray Felipe

de Orbalaes y Abreo served as medico-friars there, but they were gone by

1713. Some gossip about several of the presidio’s priests, along with some

information about Pensacola’s population, was recorded by Father François

Le Maire, a visiting priest from Mobile.

134 · William S. Coker

Le Maire arrived in Pensacola in 1712 and stayed as acting pastor for three

years. He came, he wrote, because two priests had been murdered there in

just punishment for the wicked life they led. Nothing more is known about

this incident unless it is in some way related to the murder of one priest and

the capture of another by enemy Indians in 1711. But Le Maire had more to

say about Pensacola.

The fort there, he wrote, was a “land galley,” garrisoned by 250 soldiers,

who were well known by the Indians for their cowardice. He classified the

civil population as “scum” who had escaped torture or execution in México

by being sent to Pensacola. These residents, Le Maire observed, were his

“fine parishioners.” Despite his caustic comments about Pensacola’s citizens,

Le Maire was an outstanding cartographer, whose significance in North

American mapmaking has only recently been recognized. His map of 1713

is of special interest because of the canal or channel shown on Santa Rosa

Island.

The period of peace for Pensacola lasted only from the end of Queen

Anne’s War in 1713 to the outbreak of the War of the Quadruple Alliance

in 1718. Cooperation between Pensacola and Mobile was not as good as it

had been during the war years. The French wanted to sell merchandise in

Pensacola, but Spain opposed the practice. The result was an extensive con-

proof

traband trade which was estimated, by 1717, at 12,000 pesos a year. Even so,

the French grumbled that they made little money from the Spaniards.

England, Hol and, Austria, and France formed the Quadruple Alliance

in 1718 to check the ambitions of Philip V of Spain. France declared war