The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (45 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

Sunday 22

Florence Ballard

(Detroit, Michigan, 30 June 1943)

The Supremes

Music historians have a great deal of sympathy for Florence Ballard, the ‘forgotten Supreme’ most believe was systematically conspired against by Diana Ross, Berry Gordy and the Motown machine itself. As the original lead singer of America’s biggest ever girl group, Ballard certainly appeared to have been handed a raw deal. Often overlooked in such sweeping summaries, though, is Ballard’s predominant self-destructive gene.

‘Flo’ was born the eighth of thirteen Ballard children. Like fellow Supremes Ross and Mary Wilson (plus Betty Travis, then Barbara Martin, neither of whom made the final cut), she was brought up in the Brewster Housing Project in Detroit, a vast estate close to Gordy’s Hitsville USA Studios. Often compared to Billie Holiday, Ballard was just sixteen when she was snapped up by Gordy to join a female band to support The Primes (a prototype Temptations). The entrepreneur eventually signed Ballard’s band for the newly founded Tamla Motown label in 1961, and The Primettes became The Supremes, the name suggested by Ballard, who had already assumed the role of leader and spokeswoman. After sluggish beginnings, this fresh-sounding group was coupled with the songwriting team of Holland, Dozier and Holland, and set about break-ing records left, right and centre. Beginning with ‘Where Did Our Love Go?’ and ‘Baby Love’ (1964), The Supremes racked up twelve US number ones before 1970, their sales exceeding 20 million.

But if all appeared rosy for Ballard in 1964, her world was to come crashing down around her three years later. Berry Gordy’s interest in Diana Ross was apparent from the early days, and, little by little,

she

was pushed to the fore at Ballard’s expense. The latter’s attempts to regain control were as drastic as they were ineffective: when the outspoken singer’s objections to Ross’s special treatment fell on deaf ears, she ditched her trademark beehive and began drinking before live performances. Gordy quickly lost patience, seeing Ballard as little more than a thorn in his and Ross’s side, and she was unceremoniously ousted from the group, replaced by the more amenable Cindy Birdsong (formerly of Patti Labelle & The Bluebells). (Officially, Motown suggested that Ballard’s ‘retirement’ was down to ‘the strain of touring’.) Ballard was paid off with a risible $140,000 for all future rights in 1968, while for ‘The Supremes’ one now read ‘Diana Ross & The Supremes’: the deed, as envisaged by Gordy and Ross, was done. Or so it appeared …

Her solo career with the ABC label stuttering, an increasingly desperate Ballard attempted to sue Motown in 1971 (by which time Ross had left The Supremes) for nearly $9 million, which she felt she was entitled to, describing Gordy’s ‘secret, subversive, malicious plotting and planning’. But the earlier settlement was declared legal and above board, and the case was thrown out of court, leaving Ballard near-destitute. Her marriage to inexperienced manager Tom Chapman subsequently collapsed, leaving her with three children to support alone. Her drinking, predictably, renewed apace, this time accompanied by an alarming increase in weight. While this destroyed her self-confidence as a performer, Ballard – who had no financial support from Chapman – still maintained sufficient pride to avoid asking for help elsewhere and, having lost her home in Buena Vista, was, in 1975, claiming welfare. To all intents and purposes, Ballard had returned to the housing-project world of her childhood.

A potential life-saver arrived in the form of a $50K pay-out from Motown (at the behest of Diana Ross, now flourishing as a solo artist). But this much-needed cash didn’t reverse Florence Ballard’s health problems: on the evening of 21 February, the singer – now weighing almost 200 lbs – checked herself into Mount Carmel Mercy Hospital, Michigan. Her limbs ached and she’d started to feel numbness in her extremities. Alarmed by these tell-tale signs, doctors worked through the night to save Ballard, but the former star died from coronary artery thrombosis at 10.05 the very next morning. A coroner later confirmed that Ballard had ingested an ‘unspecified’ amount of dietary pills and alcohol.

Perhaps understandably, Ross’s attempts at reconciliation with Ballard had, like the handouts and menial jobs offered to her, been routinely ignored. The die had been cast: despite more than a suggestion of contrition on her part, Ross was always portrayed as the ‘Judas’ in Ballard’s story. Five days later, Ross was roundly jeered at the well-attended but highly charged funeral service at Detroit’s New Bethel Baptist Church – the crowd of some 5,000 became hysterical and snatched floral tributes and other souvenirs from the casket as it passed.

MARCH

Friday 19

Paul Kossoff

(Hampstead, London, 14 September 1950)

Free

(Back Street Crawler)

(Black Cat Bones)

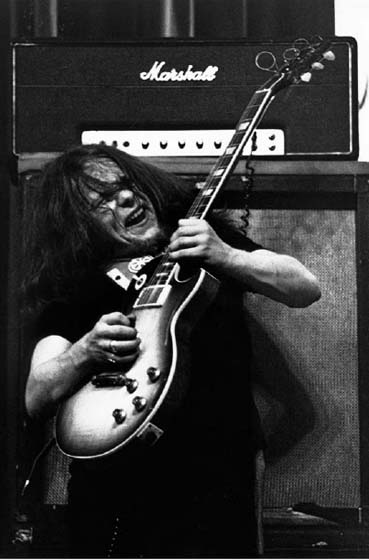

There was a time when arguably the best blues-based rock guitarists were emanating from the British Isles: beginning with Eric Clapton, a rich late-sixties lineage that included Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and Mick Taylor also gave the rock world the often-underrated Paul Kossoff. With his expressive vibrato and cleverly understated take on the blues, it’s little wonder that Kossoff – the son of British actor David Kossoff – had been classically trained as a child. What’s more surprising is that he nearly gave up the guitar at fifteen, but a decent deal on a 1954 Gibson Les Paul changed his mind – and the course of his life.

In his teens, Kossoff came into contact with a number of musicians who had a profound effect on him: one was the young Jimi Hendrix, a customer of the music centre at which Kossoff worked; another was drummer Simon Kirke, with whom Kossoff formed his first band, Black Cat Bones, becoming his long-time collaborator in Free. The pair targeted Paul Rodgers after watching the vocalist entertain the patrons of a London boozer (fourth Free-man, bassist Andy Fraser, was another teenage prodigy – with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers). By 1969 the Alexis Korner-approved Free were opening for Blind Faith on their US tour. In 1970 Free were at number two in the UK and number four in the States with future party staple, the stompalong ‘All Right Now’. Further hits arrived, mainly in their homeland, but the inconsistent reception of their albums prompted Fraser to leave in 1971. Free returned in 1972, but the early impetus had gone – Kossoff, still only twenty-one, had developed a concerning drug habit, a major factor towards Free’s capitulation in 1973.

With Rodgers and Kirke elsewhere enjoying immense success with Bad Company, Kossoff was briefly picked up by his own project, Back Street Crawler. Commercial success, though, was not as forthcoming as it had been for his former colleagues, and Kossoff’s health and spirits were noticeably declining. On 30 August 1975, the guitarist had to be revived when his heart stopped for a full half-hour – a warning sign that would have caused many to rethink their lifestyle. Not so Paul Kossoff. Still touring heavily, the guitarist was flying from Los Angeles to New York when he fell into a drug-induced coma, and died of heart failure as he slept. His father spent much of his later life campaigning against drug abuse, taking a poignant stage show about his son’s death on the road in the late seventies.

Paul Kossoff: The spirit was willing, the flesh was weak

APRIL

Friday 9

Phil Ochs

(El Paso, Texas, 19 December 1940)

He may have been a quality vocal performer and a so-so guitarist, but Phil Ochs was destined to play second fiddle to Bob Dylan during the sixties folk boom. A fan of Elvis, Buddy Holly and country music, the young Ochs was something of a daydreamer. Given his fiercely anti-military stance, it’s surprising to learn that Ochs put himself forward for military academy in Staunton, but the fragile artist believed he would come away a better person from the experience. The discipline he learned didn’t, however, prevent him from dropping out of his studies in Ohio, and Ochs fitted snugly into Greenwich Village’s folk scene on his 1962 arrival. He had a fistful of tunes and attitude to burn, thus he was ‘home’. In the wake of Dylan’s early success, Elektra seemed to agree that this self-styled ‘singing journalist’ also had something, and released his first album,

All the News That’s Fit to Sing

(1964). Subjects readily presented themselves – Cuba (he was a follower of Fidel Castro), Vietnam, civil rights – and the time seemed right for Phil Ochs. His ‘Draft Dodger Rag’ from the second long-player

Ain’t Marching Anymore

(1965) added much-needed wry humour to the genre, and became something of an anti-’Nam anthem.

Like Dylan, Ochs also took the electric route – though many thought that the added production this necessitated on his recorded output diluted essential numbers like ‘Crucifixion’. Unfazed, the singer headed to California and signed with A&M, but his constant banging on the door still failed to garner any response greater than the mild irritation of a few Democrats. His frustration was compounded when a 1968 single seemingly bound for Billboard was pulled from radio for its length and references to pot-smoking. Later album

Rehearsals For Retirement

(1969) featured his tombstone on the sleeve, the music itself displaying growing personal despair, his attitude made ever more belligerent by his intake of alcohol. The worn-down and worn-out Ochs then released a sardonic 1970 set,

Greatest Hits,

compiling a band and decking himself out in a silver lamé suit to tour the record. Then, in 1973, Ochs was set upon in a mysterious incident in Africa, mugged and almost strangled by a band of thieves; he survived but suffered severe vocal-chord damage. Two years on, he toured under the reckless alter ego of ‘John Train’, a caricature of himself he claimed had ‘killed Phil Ochs’. Unsurprisingly, friends, alienated during this phase, described him as suicidal. It came as little surprise when the ‘reborn’ Phil Ochs was found hanged at his sister’s apartment in Queens, New York. He apparently thought himself a failure, of no use to anyone – and an anachronism from an age now gone for ever.