The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars (41 page)

Read The Encyclopedia of Dead Rock Stars Online

Authors: Jeremy Simmonds

APRIL

Wednesday 23

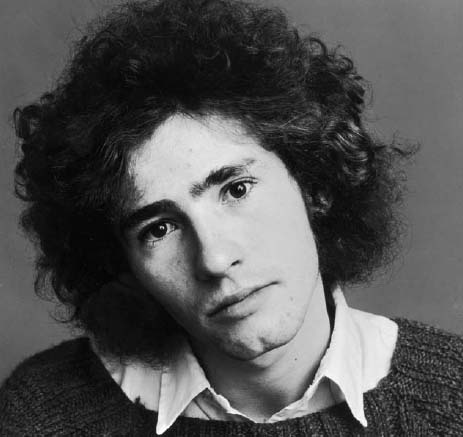

Pete Ham

(Swansea, West Glamorgan, 27 April 1947)

Badfinger

Affectionately known as ‘The Drunken Beatles’, Badfinger’s was a slower, bluesier take on the Fab Four’s sound – though most of the band were gifted songwriters in their own right. Many critics believe Badfinger could have gone on to become one of Britain’s biggest acts by the mid seventies – instead, theirs remains arguably the most tragic band fable of all.

It all started well for The Iveys (as they were once known). The band – eventually lead singer/guitarist/pianist Pete Ham, Tom Evans (rhythm/bass), Joey Molland (guitars) and Mike Gibbins (drums) – had been signed to The Beatles’ Apple label and were developing a strong relationship with various soon-to-be-ex-Beatles. Following a name change, they began an impressive run of transatlantic Top Ten entries with ‘Come and Get It’ (1970, written by Paul McCartney), ‘No Matter What’ and ‘Day After Day’ (both 1971, the latter produced by George Harrison). Something of an Apple house band, Badfinger also contributed to various Beatles’ solo projects – but with their own hits drying up all too quickly, it was a classic song for another artist that was to prove a particular

bête noire

for writers Ham and Evans.

The end came for Pete Ham following a series of legal problems between Badfinger’s management and the label (from whom they had parted company, signing with Warner Bros after an unsuccessful fourth album in 1974). The crippling disputes prevented this talented artist from either working or earning from past successes; quite simply, he was put out of service by the music business. Had Badfinger’s legal and financial dealings been better managed, Ham would have become a very wealthy man indeed – Harry Nilsson’s version of his and Evans’s ‘Without You’ topped the charts worldwide in 1972 (a 1994 mauling by Mariah Carey somehow outsold even that). This extraordinary ballad was inspired by Ham’s girlfriend, Anne Herriott – as was 1975’s ‘Helping Hand’. In this, his last ever composition, Ham appeared to be reaching out to his lover for help during the darkest period of his life. But it was too late. Warners pulled their last two albums at the point of release; Badfinger were falling apart; Pete Ham quit the line-up that spring. Desperate and confused, he polished off a bottle and hanged himself in the garage studio of the London flat he shared with Herriott, just three days before his twenty-seventh birthday and one month before the birth of the couple’s daughter, Petera. His suicide note reportedly described Badfinger’s business manager Stan Polley as a ‘soulless bastard’. One of the first to the scene, his long-time friend and colleague Tom Evans never recovered from seeing Ham’s body in that garage: he took his own life in similar circumstances eight years later

( November 1983).

November 1983).

See also

Mike Gibbins ( October 2005)

October 2005)

Friday 25

Mike Brant

(Moshé Brandt - Cyprus, 1 February 1947)

The Chocolates

A similar tale emerged from France just days after the death of Pete Ham. Pop heart-throb Mike Brant took his own life in Paris – and, once again, it was the pressures of a hungry industry that seemed to precipitate his action. Brant (or Brandt, as he was born) didn’t utter a word as a toddler; his Israeli parents feared until he turned five that he might always be mute. Far from it – their son possessed a more than decent voice and his dark looks had begun to turn heads even when working on a kibbutz as a teenager. The family had moved back to Israel, and Brant was fronting his brother’s band The Chocolates (under new identity Mickaël Sela), who began to create waves on the dinner circuit. With the group reaching low-level international status, Brant was discovered by French chanteuse Sylvie Vartan – and, though he sang purely phonetically, his ticket into the glitzy world of French pop was assured. Vartan took the young singer to France in 1969, and musical director Jean Renard (the man responsible for such ‘delights’ as Johnny Hallyday) offered Brant a five-year contract. His first single,

Laisse-moi taimer

(‘Let Me Love You’), was released in 1970 – and promptly sold 1.5 million copies to eager French housewives. The image was everything one might imagine: medallion, slashed-open shirt, vacuous expression – but the formula worked and ‘Mike Brant’ became the biggest star French pop had seen for some time.

But Brant, unwittingly, was merely a pawn. When the singer was involved in a car accident in early 1971, Renard’s first priority was to obtain photographs of him lying in hospital to sell to a national newspaper – after all, the injured singer had a new record out. The partnership was shortly dissolved. Under the new management of Charles Talar, Brant then found that the hysteria surrounding him was such that, when not performing, he had to remain locked in his room most of the time (which ended the only meaningful relationship he was to enjoy). In 1974, Brant’s world began to unravel dramatically: he experienced a breakdown on stage in Boissy-Saint-Leger, then his apartment was burgled and most of his valuables stolen (including lithographs from his friend Salvador Dalí). On 21 November 1974, the increasingly unhinged singer attempted suicide for the first time, throwing himself from a hotel window. Although friends rallied for months – and hit records

still

continued to come – Brant finally completed the deed, jumping from his apartment. As the stars of French pop music made their way to Israel for their colleague’s funeral, sales of Mike Brant’s final album topped the million mark in his adopted land. Thirty years on, his estate still benefits from more than 200,000 sales of his records every year.

Tim Buckley: Hello and goodbye

JUNE

Sunday 29

Tim Buckley

(Timothy Charles Buckley III - Washington, DC, 14 February 1947)

(The Bohemians)

In 1965, Los Angeles music review

Cheetah

heralded three newcomers to the songwriter fold – Jackson Browne, Steve Noonan and Tim Buckley. While Noonan disappeared without much trace, Browne went on to commercial stardom during the seventies. As for Buckley, he would chart, briefly, an entirely different universe altogether, his music always marginal. His highly original style was, however, to inspire following generations, its timelessness secured by his dramatic young death.

Tim Buckley’s message was unique, often emerging disguised as a series of whoops or grunts, so deeply entrenched was the singer/songwriter in his work. There were early clues: former high-school friend and co-writer Larry Beckett talked of how the young singer projected his voice to scream at buses or impersonate musical instruments. Buckley is usually referred to as a folk act, though in truth he was brought up on Johnny Cash and Hank Williams, his own music born out of gospel, jazz and soul. Buckley knew no real parameters, using his five-octave range however he chose. Commercial appreciation would always be out of reach, but Buckley – and those who had sufficient faith to record and produce his records – recognized this early in his career. Buckley and Beckett had formed a trio, The Bohemians, with another friend Jim Fielder, but it was the frontman who stood out. Buckley signed with Elektra (‘I must have listened to his demo twice a day for a week’ – Jac Holzman, producer), and an eponymous 1966 debut album set out his stall, but it was his second record,

Goodbye and Hello

(1967) that was his most – if not only – avowedly accessible work (even though it only managed a Billboard peak of 171). Strangely, this confident record arrived when his personal life was in crisis, his wife, Mary Guibert – and young son Jeffrey – estranged from the singer. Buckley’s music was almost certainly driven by the turmoil of his upbringing. Brought up in New York, then Anaheim, California, he’d felt rejected by his military father who, injured during the Second World War, often took out his rage on the good-looking young Buckley, calling him a ‘faggot’; his mother, meanwhile, believed her son would die young – because ‘that’s what poets do’. In 1970, American music-buyers were tuning into the gentler, near-MOR sounds of James Taylor or David Gates, leaving Buckley’s sixth set,

Starsailor

– an experimental work using flugelhorns and the like – to gather dust. Those who didn’t hear it missed his finest moment, ‘Song to the Siren’, a tune covered superbly in 1983 by This Mortal Coil.