The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West (12 page)

Read The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West Online

Authors: Chris Enss

BOOK: The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West

3.67Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

—Ellis Shipp, February 3, 1876

The sick baby cradled in Ellis Shipp’s arms was too weak to cry. She stared sadly up at her mother with eyes pleading for help. Ellis had none to give her suffering daughter. She had employed all of the remedies she knew to give to typhoid patients, but nothing had worked. The eight-month-old little girl languished with a fever and softly whimpered. Ellis could only hold her beloved Anna close and rock her tiny frame back and forth until at last she passed.

Ellis tearfully mourned the death of her “precious one,” but believed the Lord had great purpose in taking the child. Anna was the second baby she had lost in five years. The tragedy sparked a desire in Ellis to pursue an education in medicine. She felt her calling was inspired by God, and dedicated her life to helping preserve the lives of other mothers’ ailing children.

Doctor Ellis Reynolds Shipp was born in David County, Iowa, on January 20, 1847. She was the oldest of the five children her parents, William Fletcher Reynolds and Anna Hawley, brought into this world.

In 1852, William moved his family across the Great Plains to Utah so he could continue his work with the Mormon Church. The headquarters of the church was located in the Salt Lake Basin. The Reynolds clan settled in Pleasant Grove, 20 miles north of Salt Lake.

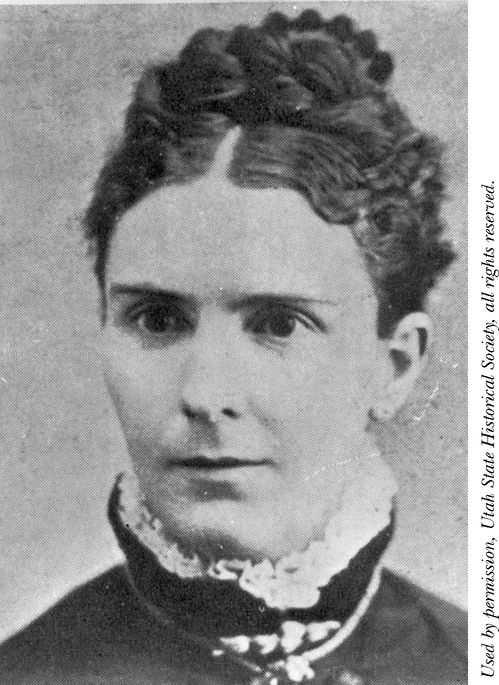

THE DEATHS OF TWO CHILDREN IN FIVE YEARS DROVE ELLIS REYNOLDS SHIPP TO THE FIELD OF MEDICINE.

According to Ellis’s journal, the first ten years of her childhood was idyllic. Her religious parents showered Ellis and her siblings with affection and attention. The death of her mother in 1861 brought an abrupt halt to what Ellis referred to as “one endless day of sunshine,” and she was thrust into the position of family caretaker—a role she would hold for more than a year.

In the fall of 1863, William Reynolds remarried. Ellis resented her new stepmother’s intrusion, and her actions reflected her feelings. She was ashamed of her behavior at times and cited her youth and inexperience as reason for her unwise outbursts of anger. In spite of a difficult period of adjustment, Ellis boasted that her father was patient with her. He continually reassured her of his love for his children, and he was a constant source of encouragement for the Reynolds clan.

At the age of twelve, Ellis gazed upon a photograph of a handsome twenty-year-old man and bragged to her friends that she would one day marry the subject of the picture. Not long after making that bold claim, Ellis met the man in the photograph at a party. “He was of noble form and feature,” she wrote in her journal. “But the principal attraction was the eyes.” Milford Shipp was just as taken with Ellis, and shortly after being introduced, the two began courting. Just as their romance began to blossom, Milford was sent on a mission trip for the Mormon Church. The two did not see each other again for five years.

During their time apart, Ellis dedicated her life to following the ways of the Mormon religion. She learned all she could about the principles and disciplines of the denomination. Brigham Young, president of the church, met the devoted teenager at a service and was moved by her level of commitment to the faith. He invited Ellis to live at his Salt Lake home as one of his children and study the word of God there. Ellis graciously accepted.

Milford’s life was as full as Ellis’s. Not only was he sharing the church’s values and teachings with spiritually hungry people at each of his mission stops, but his personal life was active as well. He had entered into a tumultuous marriage that ultimately ended in divorce.

After the dissolution of the marriage, Milford set out on another mission trip. He was to travel through the Mormon settlements across the plains and preach. When he passed through Iowa, he and Ellis were reintroduced. After hearing him speak from the pulpit, the notion that she was destined to marry Milford was reaffirmed.

Ellis and Milford’s relationship was rekindled, and seven years after their first meeting, the pair were wed in a simple ceremony. Milford was twenty-seven and Ellis was nineteen. Prior to exchanging vows, Ellis prayed to be a faithful wife and sustaining companion for her “dear Milf.” Their wedding was one of Ellis’s happiest moments. According to her journal entry dated May 5, 1866:

The ensuing few hours are somewhat confused in my mind but I know that Brother H.C. Kimball pronounced us one—and I feel that it was not all ceremony, but that our hearts were united in an indissoluble tie that all the vicissitudes of time and sorrow could not sever or unlink.

The Shipps’ first home was a fully furnished adobe cottage, and the newlyweds felt their small house was perfect. Just as they were settling into married life, Milford joined a militia to help protect their home and the Mormon emigrants from hostile Indians.

The Native Americans had killed a number of sheepherders working in the hills and canyons. Milford was among several hundred troops directed to prevent any future attacks on southern Utah residents.

During Milford’s short absence, Ellis tended her garden, made rugs and blankets for their home, pored over books on health and nutrition, and maintained a journal. When her husband returned he was greeted with news that they were expecting a baby. The first of their ten children was born early in 1867, and Ellis noted the occasion in her journal:

Our Father of Love Divine bestowed upon me His mortal child, the most gracious and sanctified gift within His storehouse of blessings. A beautiful son! A body without blemish, endowed with a sanctified spirit! My beautiful baby boy!

After a short time set aside to enjoy wife and child, Milford returned to his missionary work. Ellis was sad to see him return to the field, but she was proud of his dedication to the Lord. Her journal describes the love and admiration she had for Milford. She often noted that her passion for him was “akin to worship.” A letter from Milford, the man she believed had “no moral weakness,” temporarily halted her praise.

Milford informed Ellis that he had succumbed to the full mandate of their religion with regards to marriage, and would soon be bringing home a new wife. Ellis was devastated at first. She believed that plural marriage was a divine command from God, but she hoped she could be Milford’s “only noble aim and purpose.” After a great deal of prayer, Ellis’s heart softened to the idea of the new woman in her life and home. Her attitude was further changed with the news that she was expecting another child.

In 1875, Ellis and Milford celebrated nine years of marriage. During that time the couple had five children. Two of those children died in infancy, and one died at the age of five. Also during that time, Milford married two more women, bringing the total number of wives to four.

Throughout Ellis’s married life, she maintained a thirst for knowledge. She was an insatiable reader and would typically arise three hours before the rest of the family to study religious and secular textbooks. She shared her education with students at the ward school, where she taught a variety of practical subjects. Ellis’s chief area of interest was always medicine. She felt it was the responsibility of every mother to fully know the laws of health. Her daily routine required that she rise at four in the morning so she could spend time reviewing medical journals. The busy details of a typical day for Ellis were recounted in an 1872 journal entry:

Last night I wrote down my work for today which is as follows: Rise at four in the morning, dress, make a fire, sweep, wash in cold water, comb my hair, clean my teeth. Write a few lines in my journal. Write a letter to Grandmother. Read a chapter in Doctor Gunn on health. Read few extracts from Johnson. Dress the children, make bed, sweep, dust and prepare my room for the breakfast table. Breakfast at nine. Sew on machine until three. Dinner hour. After dinner call on Sister Jones, who is sick. Wash and prepare the children for bed; from six till eight, knit or do some other light work. Review my actions for the day—offer my devotions to Heaven and retire at nine.

Ellis’s interest in medicine did not go unnoticed by her family. Milford and his other wives encouraged her to consider attending school to pursue a degree in the field. Although many university board members, instructors, and much of the population at the time frowned upon females in the medical profession, Mormon Church leaders supported women in their faith in such ventures. The idea of Ellis attending medical school had been brought up before, but separation from her family had kept her from committing:

When the subject was broached to me, as being one to step out in this direction, I thought it would be what I would love and delight in . . . if this knowledge could be obtained here. But the thought of leaving home and loved ones overwhelmed me and swept from me even the possibility of making the attempt.

Spurred on by the memory of her three children who had died, Ellis eventually decided to brave being apart from her family to learn how she might save the lives of other infants struggling with illnesses. On November 10, 1875, Ellis boarded a train bound for Philadelphia to enroll at the Philadelphia Medical College. As she tearfully waved goodbye to her sons, she tried not to think about the fact that she would not see them again for two and a half years. Instead she focused on the opportunity to acquire further knowledge in medicine and “make her life useful upon the earth.”

Ellis’s new home in Philadelphia was a boarding house, owned and operated by members of the church. Six hours after she had arrived in the city, she was seated in one of the medical school’s halls to hear her first lecture. Her homesickness subsided as she realized how much she had to learn and how eager she was to learn it.

By January of 1876, Ellis had become fully acclimated to her surroundings and happily overwhelmed with schoolwork. In addition to lectures and laboratory studies, Ellis observed doctors making their rounds in clinics. She learned about illnesses that primarily attacked children. She noted in her journal that it was work she felt her gender was particularly suited for:

The knowledge I’m gaining now will make me more careful and more observing of little ailments in my children and meet every unfavorable symptom as it may occur. Who has greater need of understanding the laws of life and health than a woman? Truly I think she is the only one to study medicine.

A constant stream of letters from friends and relatives in Utah helped sustain Ellis through the long hours spent poring over textbooks, completing endless homework assignments, and taking grueling examinations. In her limited leisure time, she accompanied licensed doctors through hospitals and observed as they diagnosed and treated patients.

Some of the more serious cases—such as burn victims or children who had lost limbs due to accident and subsequent gangrene—stirred her emotions and left her discouraged. Overall, though, she enjoyed school and was grateful for the exposure to all ailments and their treatment. In an 1876 journal entry, her enthusiasm seemed boundless:

How much to learn! I feel overwhelmed with the multifarious intricacies of medical education. Truly the greatest study of mankind is man, both physically and mentally.

No matter how busy Ellis stayed with class work and field assignments, a deep longing for her children and husband would overtake her at times. Some days she was too lonesome to keep up with her daily journal. She dragged her sorrowful and weary frame from lecture to lecture, believing in those moments the only thing that could get her through another day was the sight of her sons. Acute melancholy and the cold air in the lab where Ellis and other classmates practiced dissection contributed to a failure in her own health. Although she felt dissection was necessary for learning about the intricacies of the human body, she found the practice of mutilating the body disconcerting. As she grew accustomed to the practice, her health was restored and the horrifying dread of the work itself wore off:

All disagreeable sensations are lost in wonder and admiration. Most truly man is the greatest work of God. Every bone, muscle, tendon, vein, artery, and nerve seem to me to bear the impress of divine intelligence.

Other books

Give Me Everything You Have: On Being Stalked by Lasdun, James

The Last Boat Home by Dea Brovig

Linda Kay Silva - Delta Stevens 3 - Weathering the Storm by Linda Kay Silva

Small Bamboo by Tracy Vo

Marine Ever After (Always a Marine) by Long, Heather

Riding Danger by Candice Owen

How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia by Mohsin Hamid

Bajo el hielo by Bernard Minier

His Assurance (Assured Distraction Book 3) by Thia Finn

A Voice In The Night by Matthews, Brian