The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West (15 page)

Read The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West Online

Authors: Chris Enss

BOOK: The Doctor Wore Petticoats: Women Physicians of the Old West

3.87Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

In 1897, she purchased a homestead on the Double D Ranch in Wyoming. In addition to maintaining her two medical practices, she was also now working her land.

The labor involved in keeping up with all three projects was overwhelming at times, and her health began to suffer from the effort. On February 1, 1901, Doctor Stanford died of heart complications at age sixty-two. Funeral services were conducted at her graveside with her son Victor and many of her friends and patients in attendance. A

Deadwood Pioneer Times

article, published shortly after her death, lamented the loss:

Deadwood Pioneer Times

article, published shortly after her death, lamented the loss:

Notwithstanding that she has busied herself with her profession and domestic life, yet she has taken a lively interest in public affairs, she has been prominent in the work of the churches and societies, and her name has been associated in one way or another with almost every laudable enterprise in the city where her assistance was welcome. She was for a number of years a member of the Board of Education of Deadwood, and in that capacity she rendered a valuable service. . . . Tenderly the last offices were performed and the form of her who had been mother, friend, and medical advisor to numbers of struggling and benighted souls was lowered into the narrow home amid a flood of silent tears.

A plaque honoring her contributions hangs in the main reading room of Deadwood’s public library.

FRONTIER MEDICINE

In the early 1850s, pioneers invaded the majestic plains west of the Mississippi, hauling with them every conceivable provision necessary for life on the new frontier. Among the supplies the emigrants brought along were tents and bedding, cooking utensils, furniture, tools, and extra clothing. Most, if not all, of the items listed could be abandoned if necessary to lighten the load and make room for essentials such as food and medicine.

Women on the wagon trains were responsible not only for preparing the food and making it last through the journey but were also in charge of overall healthcare for the others. Armed with herbal medicine kits and journals filled with remedies, women administered doses of juniper berries, garlic, and bitter roots to cure the ailing. These “granny remedies,” as they were called, were antidotes for a variety of illnesses from nausea to typhoid. They were a combination of superstition, religious beliefs, and advice passed down from generation to generation.

Not only did female doctors have to withstand prejudice against their sex, they also had to fight against barbaric remedies that had been passed down from generation to generation. Myths—such as believing a person could preserve his teeth and eliminate mouth odor by rinsing his mouth every morning with his own urine, or that mold scraped from cheese could heal open sores—had to be dispelled.

Some medicines, like herb teas and drawing poultices, brought relief, but most had no effect at all. Indeed many of these remedies did more harm than good. Arsenic, for example, was used to treat heart palpitations and syphilis. Cod-liver oil and onion stew were used to help tuberculosis sufferers, and egg whites and beeswax were used to treat burns. Many of the remedies were based on false notions acquired from ancient books, which instructed sufferers to cure sore throats, for instance, by wearing a piece of bacon sprinkled with black pepper around the neck.

A list of frontier remedies assembled by the Missouri State Historical Society shows why historians refer to this time period as the “Golden Age of Medical Quackery.”

The hot blood of chickens cures shingles.

Tea made from the scrapings of stallion hooves cures hives.

Wrap legs in brown paper soaked in vinegar to relieve aching muscles.

Gold filings in honey restore energy.

Carry a horse chestnut to ward off rheumatism.

Watermelon seeds boiled in water help eliminate kidney troubles.

Sassafras tea thickens the blood.

The juice of a green walnut cures ringworms.

Treat chapped hands with salve of kerosene and beef tallow.

Use a mashed potato poultice to draw out the core of a boil.

To remove warts, rub them with green walnuts, bacon rind, or chicken feet.

Use the ointment of crushed sheep sorrel leaves and gunpowder for skin cancer.

Mashed snails and earthworms in water are good for diphtheria.

Common salt with scrapings from pewter spoons for treating worms.

Boiled pumpkin seed tea for stomach worms.

Scorpion oil as a diuretic in venereal disease.

Tea made from steeping dried chicken gizzard linings in hot water for stomachaches.

Use wood ashes or cobwebs to stop excessive bleeding.

Brandy and red pepper for cholera.

Use mold scraped from cheese or old bread for open sores.

Carry an onion in your pocket to prevent smallpox.

Wear a bag of asafetida around the neck to cure a cold.

The oil of geese, wolves, bears, or polecats are good for rheumatism.

Use the salve of lard and brimstone for an itch.

Mashed cabbage for ulcers or cancer of the breast.

Use two tablespoons of India ink to eliminate tapeworm.

Onions boiled in molasses are good as a laxative.

Warm brains of a freshly killed rabbit applied to a teething child’s gums will relieve the pain.

Scratch gums with an iron nail until it bleeds, then drive the nail into a wooden beam to relieve toothaches.

Owl broth cures whooping cough.

The blood of a “bessie bug” dropped in the ear will cure an earache.

Oddly enough, rattlesnake bites were handled in the same manner as audiences have seen cowboys treat them in films. The bite wound would be sliced open and the poison would be sucked out. If this were done right away, the patient had a good chance for survival.

Before dentists arrived on the frontier, pioneers suffering with toothaches generally sought help from barbers. If a doctor was available, he would provide whatever care was needed. Generally, the problem was dealt with by extracting the offensive tooth using a pair of crude pliers. Whisky and other alcoholic beverages were the only form of anesthetic available at that time.

Most emigrants who made their way west did not practice any kind of dental care. As a result rotten teeth and bad breath were commonplace. Toothbrushes were available in country stores by the late 1850s, as well as soap and chalk toothpastes. However, not everyone used them. Dentists wouldn’t become common on the frontier until the 1870s. The average citizen was completely toothless by the time he or she reached fifty.

ADVERTISEMENTS AND WOMEN PHYSICIANS

If I had had cholera, hydrophobia, smallpox, or any malignant

disease, I could not have been more avoided than I was.

—Doctor Harriet Hunt, first woman to practice

medicine successfully in the United States, 1835

medicine successfully in the United States, 1835

The difficult trek across the plains and deserts of the frontier, to Rocky Mountain destinations and beyond, was viewed by the first women physicians as just another obstacle to overcome on the way to achieving their goal. They wanted to practice medicine and believed they would have a chance to do that in the mining camps and cow towns in the West. Initial attempts to practice their profession sent shock waves through the deeply patriarchal society.

Doctor Elise Pfeiffer Stone was subjected to a barrage of ridicule and criticism after an article about her practice ran in the March 5, 1888, edition of a Nevada City, California newspaper:

LADY PHYSICIAN—MRS. E. STONE, WHO IS, WE LEARN, A THOROUGHLY EDUCATED AND ACCOMPLISHED PHYSICIAN, HAS ESTABLISHED HERSELF IN SELBY FLAT, AND OFFERS HER SERVICES TO THE LADIES OF NEVADA AN VICINITY. SHE IS A GRADUATE OF A GERMAN UNIVERSITY AND HAS ENJOYED CONSIDERABLE PRACTICE, SPEAKS SEVERAL LANGUAGES &C.

Doctor Stone’s medical knowledge was challenged publicly and frequently by male colleagues who insisted women were not smart enough to be doctors. Eight months after opening her practice in the Gold Country, her professional reputation was slandered by a local physician. In a lengthy article found in the

Nevada Journal,

Doctor Stone articulately responded to her critics:

Nevada Journal,

Doctor Stone articulately responded to her critics:

In all my professional career I have not had occasion to defend myself against slander intended to injure my professional reputation before; I have practiced for some time as Physician and Midwife in Germany my native home; in N.Y. City and in Buffalo, N.Y., and have been in the high estimation of the profession and the public so far as I am known, which a reference to Dr. L.A. Wolfe of N.Y. or Professor White of Buffalo will testify. The circumstances which calls forth this card [article] is certain false and slanderous remarks which have come to my ears from one calling himself a physician. The last I heard was a sarcastic remark that “he would like to see me in a difficult case of midwifery.”Now it is sympathy with my sex at the cruelties practiced on them by men in medical practice for want of knowledge in the profession, that chiefly induced me to remain here, and if that gentlemen or any other will be kind enough, to present me with a difficult case, I will attend it with a great deal of pleasure, that he and the public may form and estimate of my capacity. I have attended 2000 cases of midwifery, among which, I presume, I have had as difficult cases as have fallen to the share of any physician in the country, but how I performed my duties and with what results, I leave others and time in this country to testify; suffice it to say, I challenge any one or number of physicians to prove

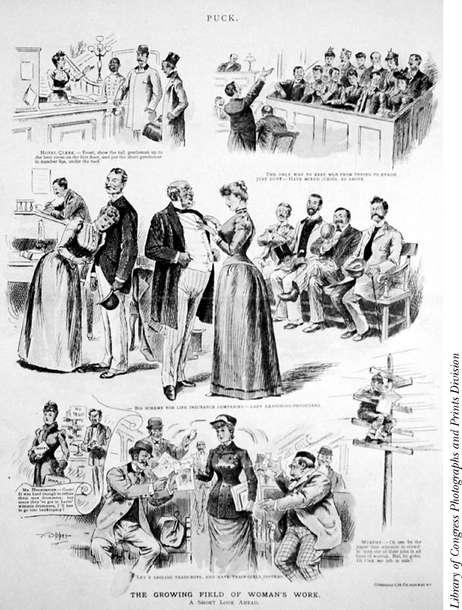

me inferior, in female practice, to any physician in California. My diploma can be seen at my residence, which will testify that in midwifery, medical operations, and the use of instruments in all forms required in medical practice, I have perfected my studies to the satisfaction and unanimous approbation of the whole board of professors. Medicines and supporting instruments of all kinds required by females to be had at my residence.THIS CONTROVERSIAL ADVERTISEMENT APPEARED IN MANY WOMEN’S MAGAZINES IN 1891. IT SHOWS THE PROGRESS WOMEN WERE MAKING IN MALE-DOMINATED FIELDS, INCLUDING THE MEDICAL PROFESSION.

Other books

Deadly Pursuit by Irene Hannon

Attachments by Rainbow Rowell

Escape from the Damned (APEX Predator Book 2) by Glyn Gardner

Mr. Splitfoot by Samantha Hunt

The Boyfriend Bylaws by Susan Hatler

Broken by Barnholdt, Lauren, Gorvine, Aaron

The Love Letter by Brenna Aubrey

Impressions of Africa (French Literature Series) by Roussel, Raymond

The Hopeless Hoyden by Bennett, Margaret

Perfume River by Robert Olen Butler