The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (50 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

For the forty years of the Cold War, conflict permeated downward as the superpowers attempted to recruit allies and partners and to subvert, convert, or neutralize the allies and partners of the other superpower. Competition was, of course, most intense in the Third World, with new and weak states pressured by the superpowers to join the great global contest. In the post-Cold War world, multiple communal conflicts have superseded the single superpower conflict. When these communal conflicts involve groups from different civilizations, they tend to expand and to escalate. As the conflict becomes more intense, each side attempts to rally support from countries and groups belonging to its civilization. Support in one form or another, official or unofficial, overt or covert, material, human, diplomatic, financial, symbolic, or military, is always forthcoming from one or more kin countries or groups. The longer a fault line conflict continues the more kin countries are likely to become involved in supporting, constraining, and mediating roles. As a result of this “kin-country syndrome,” fault line conflicts have a much higher potential for escalation than do intracivilizational conflicts and usually require intercivilizational cooperation to contain and end them. In contrast to the Cold War, conflict does not flow down from above, it bubbles up from below.

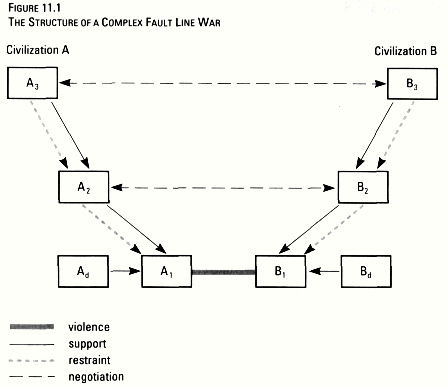

States and groups have different levels of involvement in fault line wars. At the primary level are those parties actually fighting and killing each other. These may be states, as in the wars between India and Pakistan and between Israel and its neighbors, but they may also be local groups, which are not states or are, at best, embryonic states, as was the case in Bosnia and with the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians. These conflicts may also involve secondary level participants, usually states directly related to the primary parties, such as the governments of Serbia and Croatia in the former Yugoslavia, and those of Armenia and Azerbaijan in the Caucasus. Still more remotely connected with the conflict are tertiary states, further removed from the actual fighting but having civilizational ties with the participants, such as Germany, Russia, and the Islamic states with respect to the former Yugoslavia; and Russia, Turkey, and Iran in the case of the Armenian-Azeri dispute. These third level partici

p. 273

pants often are the core states of their civilizations. Where they exist, the diasporas of primary level participants also play a role in fault line wars. Given the small numbers of people and weapons usually involved at the primary level, relatively modest amounts of external aid, in the form of money, weapons, or volunteers, can often have a significant impact on the outcome of the war.

The stakes of the other parties to the conflict are not identical with those of primary level participants. The most devoted and wholehearted support for the primary level parties normally comes from diaspora communities who intensely identify with the cause of their kin and become “more Catholic than the Pope.” The interests of second and third level governments are more complicated. They also usually provide support to first level participants, and even if they do not do so, they are suspected of doing so by opposing groups, which justifies the latter supporting their kin. In addition, however, second and third level governments have an interest in containing the fighting and not becoming directly involved themselves. Hence while supporting primary level participants, they also attempt to restrain those participants and to induce them to moderate their objectives. They also usually attempt to negotiate with their second and third level counterparts on the other side of the fault line and thus prevent a local war from escalating into a broader war involving core states.

Figure 11.1

outlines the relationships of these potential parties to fault line wars. Not all such wars have had this full cast of characters, but several have, including those in the former Yugoslavia and the Transcaucasus, and almost any fault line war potentially could expand to involve all levels of participants.

In one way or another, diasporas and kin countries have been involved in every fault line war of the 1990s. Given the extensive primary role of Muslim groups in such wars, Muslim governments and associations are the most frequent secondary and tertiary participants. The most active have been the governments of Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, and Libya, who together, at times with other Muslim states, have contributed varying degrees of support to Muslims fighting non-Muslims in Palestine, Lebanon, Bosnia, Chechnya, the Transcaucasus, Tajikistan, Kashmir, Sudan, and the Philippines. In addition to governmental support, many primary level Muslim groups have been bolstered by the floating Islamist international of fighters from the Afghanistan war, who have joined in conflicts ranging from the civil war in Algeria to Chechnya to the Philippines. This Islamist international was involved, one analyst noted, in the “dispatch of volunteers in order to establish Islamist rule in Afghanistan, Kashmir, and Bosnia; joint propaganda wars against governments opposing Islamists in one country or another; the establishment of Islamic centers in the diaspora that serve jointly as political headquarters for all of those parties.”

[16]

The Arab League and the Organization of the Islamic Conference have also provided support for and attempted to coordinate the efforts of their members in reinforcing Muslim groups in intercivilizational conflicts.

Figure 11.1 – The Structure of a Complex Fault Line War

The Soviet Union was a primary participant in the Afghanistan War, and in

p. 274

the post-Cold War years Russia has been a primary participant in the Chechen War, a secondary participant in the Tajikistan fighting, and a tertiary participant in the former Yugoslav wars. India has had a primary involvement in Kashmir and a secondary one in Sri Lanka. The principal Western states have been tertiary participants in the Yugoslav contests. Diasporas have played a major role on both sides of the prolonged struggles between Israelis and Palestinians, as well as in supporting Armenians, Croatians, and Chechens in their conflicts. Through television, faxes, and electronic mail, “the commitments of diasporas are reinvigorated and sometimes polarized by constant contact with their former homes; ‘former’ no longer means what it did.”

[17]

In the Kashmir war Pakistan provided explicit diplomatic and political support to the insurgents and, according to Pakistani military sources, substantial amounts of money and weapons, as well as training, logistical support, and a sanctuary. It also lobbied other Muslim governments on their behalf. By 1995 the insurgents had reportedly been reinforced by at least 1,200

mujahedeen

fighters from Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Sudan equipped with Stinger missiles and other weapons supplied by the Americans for their war against the Soviet Union.”

[18]

The Moro insurgency in the Philippines benefited for a time from funds and equipment from Malaysia; Arab governments provided additional funds; several thousands insurgents were trained in Libya; and the extremist

p. 275

insurgent group, Abu Sayyaf, was organized by Pakistani and Afghan fundamentalists.

[19]

In Africa Sudan regularly helped the Muslim Eritrean rebels fighting Ethiopia, and in retaliation Ethiopia supplied “logistic and sanctuary support” to the “rebel Christians” fighting Sudan. The latter also received similar aid from Uganda, reflecting in part its “strong religious, racial, and ethnic ties to the Sudanese rebels.” The Sudanese government, on the other hand, got $300 million in Chinese arms from Iran and training from Iranian military advisers, which enabled it to launch a major offensive against the rebels in 1992. A variety of Western Christian organizations provided food, medicine, supplies, and, according to the Sudanese government, arms to the Christian rebels.

[20]

In the war between the Hindu Tamil insurgents and the Buddhist Sinhalese government in Sri Lanka, the Indian government originally provided substantial support to the insurgents, training them in southern India and giving them weapons and money. In 1987 when Sri Lankan government forces were on the verge of defeating the Tamil Tigers, Indian public opinion was aroused against this “genocide” and the Indian government airlifted food to the Tamils “in effect signaling [President] Jayewardene that India intended to prevent him from crushing the Tigers by force.”

[21]

The Indian and Sri Lankan governments then reached an agreement that Sri Lanka would grant a considerable measure of autonomy to the Tamil areas and the insurgents would turn in their weapons to the Indian army. India deployed 50,000 troops to the island to enforce the agreement, but the Tigers refused to surrender their arms and the Indian military soon found themselves engaged in a war with the guerrilla forces they had previously supported. The Indian forces were withdrawn beginning in 1988. In 1991 the Indian prime minister, Rajiv Gandhi, was murdered, according to Indians by a supporter of the Tamil insurgents, and the Indian government’s attitude toward the insurgency became increasingly hostile. Yet the government could not stop the sympathy and support for the insurgents among the 50 million Tamils in southern India. Reflecting this opinion, officials of the Tamil Nadu government, in defiance of New Delhi, allowed the Tamil Tigers to operate in their state with a “virtually free run” of their 500-mile coast and to send supplies and weapons across the narrow Palk Strait to the insurgents in Sri Lanka.

[22]

Beginning in 1979 the Soviets and then the Russians became engaged in three major fault line wars with their Muslim neighbors to the south: the Afghan War of 1979-1989, its sequel the Tajikistan war that began in 1992, and the Chechen war that began in 1994. With the collapse of the Soviet Union a successor communist government came to power in Tajikistan. This government was challenged in the spring of 1922, by an opposition composed of rival regional and ethnic groups, including both secularists and Islamists. This opposition, bolstered by weapons from Afghanistan, drove the pro-Russian government out of the capital, Dushanbe, in September 1992. The Russian and Uzbekistan governments reacted vigorously, warning of the spread of Is

p. 276

lamic fundamentalism. The Russian 201st Motorized Rifle Division, which had remained in Tajikistan, provided arms to the progovemment forces, and Russia dispatched additional troops to guard the border with Afghanistan. In November 1992 Russia, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan agreed on Russian and Uzbek military intervention ostensibly for peacekeeping but actually to participate in the war. With this support plus Russian arms and money, the forces of the former government were able to recapture Dushanbe and establish control over much of the country. A process of ethnic cleansing followed, and opposition refugees and troops retreated into Afghanistan.

Middle Eastern Muslim governments protested the Russian military intervention. Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan assisted the increasingly Islamist opposition with money, arms, and training. In 1993 reportedly many thousand fighters were being trained by the Afghan

mujahedeen,

and in the spring and summer of 1993, the Tajik insurgents launched several attacks across the border from Afghanistan killing a number of Russian border guards. Russia responded by deploying more troops to Tajikistan and delivering “a massive artillery and mortar” barrage and air attacks on targets in Afghanistan. Arab governments, however, supplied the insurgents with funds to purchase Stinger missiles to counter the aircraft. By 1995 Russia had about 25,000 troops deployed in Tajikistan and was providing well over half the funds necessary to support its government. The insurgents, on the other hand, were actively supported by the Afghanistan government and other Muslim states. As Barnett Rubin pointed out, the failure of international agencies or the West to provide significant aid to either Tajikistan or Afghanistan made the former totally dependent on the Russians and the latter dependent upon their Muslim civilizational kin. “Any Afghan commander who hopes for foreign aid today must either cater to the wishes of the Arab and Pakistani funders who wish to spread the

jihad

to Central Asia or join the drug trade.”

[23]

Russia’s third anti-Muslim war, in the North Caucasus with the Chechens, had a prologue in the fighting in 1992-1993 between the neighboring Orthodox Ossetians and Muslim Ingush. The latter together with the Chechens and other Muslim peoples were deported to central Asia during World War II. The Ossetians remained and took over Ingush properties. In 1956-1957 the deported peoples were allowed to return and disputes commenced over the ownership of property and the control of territory. In November 1992 the Ingush launched attacks from their republic to regain the Prigorodny region, which the Soviet government had assigned to the Ossetians. The Russians responded with a massive intervention including Cossack units to support the Orthodox Ossetians. As one outside commentator described it: “In November 1992, Ingush villages in Ossetia were surrounded and shelled by Russian tanks. Those who survived the bombing were killed or taken away. The massacre was carried out by Ossetian OMON [special police] squads, but Russian troops sent to the region ‘to keep the peace’ provided their cover.”

[24]

It was,

The Economist

re

p. 277

ported, “hard to comprehend that so much destruction had taken place in less than a week.” This was “the first ethnic-cleansing operation in the Russian federation.” Russia then used this conflict to threaten the Chechen allies of the Ingush, which, in turn, “led to the immediate mobilization of Chechnya and the [overwhelmingly Muslim] Confederation of the Peoples of the Caucasus (KNK). The KNK threatened to send 500,000 volunteers against the Russian forces if they did not withdraw from Chechen territory. After a tense standoff, Moscow backed down to avoid the escalation of the North Ossetian-Ingush conflict into a regionwide conflagration.”

[25]