The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (47 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

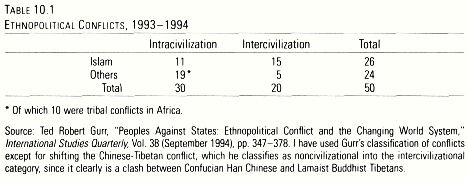

1. Muslims were participants in twenty-six of fifty ethnopolitical conflicts in 1993-1994 analyzed in depth by Ted Robert Gun (

Table 10.1

). Twenty of these conflicts were between groups from different civilizations, of which fifteen were between Muslims and non-Muslims. There were, in short, three times as many intercivilizational conflicts involving Muslims

p. 257

as there were conflicts between all non-Muslim civilizations. The conflicts within Islam also were more numerous than those in any other civilization, including tribal conflicts in Africa. In contrast to Islam, the West was involved in only two intracivilizational and two intercivilizational conflicts. Conflicts involving Muslims also tended to be heavy in casualties. Of the six wars in which Gurr estimates that 200,000 or more people were killed, three (Sudan, Bosnia, East Timor) were between Muslims and non-Muslims, two (Somalia, Iraq-Kurds) were between Muslims, and only one (Angola) involved only non-Muslims.

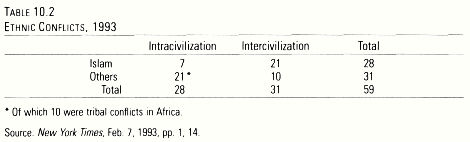

2. The

New York Times

identified forty-eight locations in which some fifty-nine ethnic conflicts were occurring in 1993. In half these places Muslims were clashing with other Muslims or with non-Muslims. Thirty-one of the fifty-nine conflicts were between groups from different civilizations, and, paralleling Gurr’s data, two-thirds (twenty-one) of these intercivilizational conflicts were between Muslims and others (

Table 10.2

).

3. In yet another analysis, Ruth Leger Sivard identified twenty-nine wars (defined as conflicts involving 1000 or more deaths in a year) under way in 1992. Nine of twelve intercivilizational conflicts were between Muslims and non-Muslims, and Muslims were once again fighting more wars than people from any other civilization.

[24]

Table 10.1 – Ethnopolitical Conflicts, 1993-1994

Table 10.2 – Ethnic Conflicts, 1993

Three different compilations of data thus yield the same conclusion: In the early 1990s Muslims were engaged in more intergroup violence than were

p. 258

non-Muslims, and two-thirds to three-quarters of intercivilizational wars were between Muslims and non-Muslims. Islam’s borders

are

bloody, and so are its innards.

[F10]

The Muslim propensity toward violent conflict is also suggested by the degree to which Muslim societies are militarized. In the 1980s Muslim countries had military force ratios (that is, the number of military personnel per 1000 population) and military effort indices (force ratio adjusted for a country’s wealth) significantly higher than those for other countries. Christian countries, in contrast, had force ratios and military effort indices significantly lower than those for other countries. The average force ratios and military effort ratios of Muslim countries were roughly twice those of Christian countries (

Table 10.3

). “Quite clearly,” James Payne concludes, “there is a connection between Islam and militarism.”

[25]

Table 10.3 – Militarism of Muslim and Christian Countries

Muslim states also have had a high propensity to resort to violence in international crises, employing it to resolve 76 crises out of a total of 142 in which they were involved between 1928 and 1979. In 25 cases violence was the primary means of dealing with the crisis; in 51 crises Muslim states used violence in addition to other means. When they did use violence, Muslim states used high-intensity violence, resorting to full-scale war in 41 percent of the cases where violence was used and engaging in major clashes in another 38 percent of the cases. While Muslim states resorted to violence in 53.5 percent of their crises, violence was used by the United Kingdom in only 11.5 percent, by the United States in 17.9 percent, and by the Soviet Union in 28.5 percent of the crises in which they were involved. Among the major powers only China’s violence propensity exceeded that of the Muslim states: it employed violence in 76.9 percent of its crises.

[26]

Muslim bellicosity and violence are late-twentieth-century facts which neither Muslims nor non-Muslims can deny.

p. 259

What was responsible for the late-twentieth-century upsurge in fault line wars and for the central role of Muslims in such conflicts? First, these wars had their roots in history. Intermittent fault line violence between different civilizational groups occurred in the past and existed in present memories of the past, which in turn generated fears and insecurities on both sides. Muslims and Hindus on the Subcontinent, Russians and Caucasians in the North Caucasus, Armenians and Turks in the Transcaucasus, Arabs and Jews in Palestine, Catholics, Muslims, and Orthodox in the Balkans, Russians and Turks from the Balkans to Central Asia, Sinhalese and Tamils in Sri Lanka, Arabs and blacks across Africa: these are all relationships which through the centuries have involved alternations between mistrustful coexistence and vicious violence. A historical legacy of conflict exists to be exploited and used by those who see reason to do so. In these relationships history is alive, well, and terrifying.

A history of off-again-on-again slaughter, however, does not itself explain why violence was on again in the late twentieth century. After all, as many pointed out, Serbs, Croats, and Muslims for decades lived ve ry peacefully together in Yugoslavia. Muslims and Hindus did so in India. The many ethnic and religious groups in the Soviet Union coexisted, with a few notable exceptions produced by the Soviet government. Tamils and Sinhalese also lived quietly together on an island often described as a tropical paradise. History did not prevent these relatively peaceful relationships prevailing for substantial periods of time; hence history, by itself, cannot explain the breakdown of peace. Other factors must have intruded in the last decades of the twentieth century.

Changes in the demographic balance were one such factor. The numerical expansion of one group generates political, economic, and social pressures on other groups and induces countervailing responses. Even more important, it produces military pressures on less demographically dynamic groups. The collapse in the early 1970s of the thirty-year-old constitutional order in Lebanon was in large part a result of the dramatic increase in the Shi’ite population in relation to the Maronite Christians. In Sri Lanka, Gary Fuller has shown, the peaking of the Sinhalese nationalist insurgency in 1970 and of the Tamil insurgency in the late 1980s coincided exactly with the years when the fifteen-to-twenty-four-year-old “youth bulge” in those groups exceeded 20 percent of the total population of the group.

[27]

(See

Figure 10.1

.) The Sinhalese insurgents, one U.S. diplomat to Sri Lanka noted, were virtually all under twenty-four years of age, and the Tamil Tigers, it was reported, were “unique in their reliance on what amounts to a children’s army,” recruiting “boys and girls as young as eleven,” with those killed in the fighting “not yet teenagers when they died, only a few older than eighteen.” The Tigers,

The Economist

observed, were waging an “under-age war.”

[28]

In similar fashion, the fault line wars between Russians and the Muslim peoples to their south were fueled by major

p. 260

differences in population growth. In the early 1990s the fertility rate of women in the Russian Federation was 1.5, while in the primarily Muslim Central Asian former Soviet republics the fertility rate was about 4.4 and the rate of net population increase (crude birth rate minus crude death rate) in the late 1980s in the latter was five to six times that in Russia. Chechens increased by 26 percent in the 1980s and Chechnya was one of the most densely populated places in Russia, its high birth rates producing migrants and fighters.

[29]

In similar fashion high Muslim birth rates and migration into Kashmir from Pakistan stimulated renewed resistance to Indian rule.

Figure 10.1 – Sri Lanka: Sinhalese and Tamil Youth Bulges

The complicated processes that led to intercivilizational wars in the former Yugoslavia had many causes and many starting points. Probably the single most important factor leading to these conflicts, however, was the demographic shift that took place in Kosovo. Kosovo was an autonomous province within the Serbian republic with the de facto powers of the six Yugoslav republics except the right to secede. In 1961 its population was 67 percent Albanian Muslim and 24 percent Orthodox Serb. The Albanian birth rate, however, was the highest in Europe, and Kosovo became the most densely populated area of Yugoslavia. By the 1980s close to 50 percent of the Albanians were less than twenty years old. Facing those numbers, Serbs emigrated from Kosovo in pursuit of economic opportunities in Belgrade and elsewhere. As a result, in 1991 Kosovo was 90 percent Muslim and 10 percent Serb.

[30]

Serbs, nonetheless, viewed Kosovo as their “holy land” or “Jerusalem,” the site, among other things, of the great battle on June 28, 1389, when they were defeated by the Ottoman Turks and, as a result, suffered Ottoman rule for almost five centuries.

By the late 1980s the shifting demographic balance led the Albanians to demand that Kosovo be elevated to the status of a Yugoslav republic. The Serbs and the Yugoslav government resisted, afraid that once Kosovo had the right to secede it would do so and possibly merge with Albania. In March 1981 Albanian protests and riots erupted in support of their demands for republic status.

p. 261

According to Serbs, discrimination, persecution, and violence against Serbs subsequently intensified. “In Kosovo from the late 1970s on,” observed a Croatian Protestant, “. . . numerous violent incidents took place which included property damage, loss of jobs, harassment, rapes, fights, and killings.” As a result, the “Serbs claimed that the threat to them was of genocidal proportions and that they could no longer tolerate it.” The plight of the Kosovo Serbs resonated elsewhere within Serbia and in 1986 generated a declaration by 200 leading Serbian intellectuals, political figures, religious leaders, and military officers, including editors of the liberal opposition journal

Praxis,

demanding that the government take vigorous measures to end the genocide of Serbs in Kosovo. By any reasonable definition of genocide, this charge was greatly exaggerated, although according to one foreign observer sympathetic to the Albanians, “during the 1980s Albanian nationalists were responsible for a number of violent assaults on Serbs, and for the destruction of some Serb property.”

[31]