The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (48 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

All this aroused Serbian nationalism and Slobodan Milosevic saw his opportunity. In 1987 he delivered a major speech at Kosovo appealing to Serbs to claim their own land and history. “Immediately a great number of Serbs—communist, noncommunist and even anticommunist—started to gather around him, determined not only to protect the Serbian minority in Kosovo, but to suppress the Albanians and turn them into second-class citizens. Milosevic was soon acknowledged as a national leader.”

[32]

Two years later, on 28 June 1989, Milosevic returned to Kosovo together with 1 million to 2 million Serbs to mark the 600th anniversary of the great battle symbolizing their ongoing war with the Muslims.

The Serbian fears and nationalism provoked by the rising numbers and power of the Albanians were further heightened by the demographic changes in Bosnia. In 1961 Serbs constituted 43 percent and Muslims 26 percent of the population of Bosnia-Herzegovina. By 1991 the proportions were almost exactly reversed: Serbs had dropped to 31 percent and Muslims had risen to 44 percent. During these thirty years Croats went from 22 percent to 17 percent. Ethnic expansion by one group led to ethnic cleansing by the other. “Why do we kill children?” one Serb fighter asked in 1992 and answered, “Because someday they will grow up and we will have to kill them then.” Less brutally Bosnian Croatian authorities acted to prevent their localities from being “demographically occupied” by the Muslims.

[33]

Shifts in the demographic balances and youth bulges of 20 percent or more account for many of the intercivilizational conflicts of the late twentieth century. They do not, however, explain all of them. The fighting between Serbs and Croats, for instance, cannot be attributed to demography and, for that matter, only partially to history, since these two peoples lived relatively peacefully together until the Croat Ustashe slaughtered Serbs in World War II. Here and elsewhere politics was also a cause of strife. The collapse of the

p. 262

Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian empires at the end of World War I stimulated ethnic and civilizational conflicts among successor peoples and states. The end of the British, French, and Dutch empires produced similar results after World War II. The downfall of the communist regimes in the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia did the same at the end of the Cold War. People could no longer identify as communists, Soviet citizens, or Yugoslavs, and desperately needed to find new identities. They found them in the old standbys of ethnicity and religion. The repressive but peaceful order of states committed to the proposition that there is no god was replaced by the violence of peoples committed to different gods.

This process was exacerbated by the need for the emerging political entities to adopt the procedures of democracy. As the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia began to come apart, the elites in power did not organize national elections. If they had done so, political leaders would have competed for power at the center and might have attempted to develop multiethnic and multicivilizational appeals to the electorate and to put together similar majority coalitions in parliament. Instead, in both the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia elections were first organized on a republic basis, which created the irresistible incentive for political leaders to campaign against the center, to appeal to ethnic nationalism, and to promote the independence of their republics. Even within Bosnia the populace voted strictly along ethnic lines in the 1990 elections. The multiethnic Reformist Party and the former communist party each got less than 10 percent of the vote. The votes for the Muslim Party of Democratic Action (34 percent), the Serbian Democratic Party (30 percent), and the Croatian Democratic Union (18 percent) roughly approximated the proportions of Muslims, Serbs, and Croats in the population. The first fairly contested elections in almost every former Soviet and former Yugoslav republic were won by political leaders appealing to nationalist sentiments and promising vigorous action to defend their nationality against other ethnic groups. Electoral competition encourages nationalist appeals and thus promotes the intensification of fault line conflicts into fault line wars. When, in Bogdan Denitch’s phrase, “ethnos becomes demos,”

[34]

the initial result is

polemos

or war.

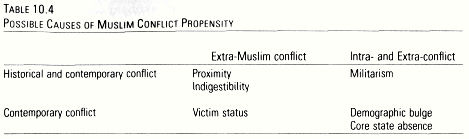

The question remains as to why, as the twentieth century ends, Muslims are involved in far more intergroup violence than people of other civilizations. Has this always been the case? In the past Christians killed fellow Christians and other people in massive numbers. To evaluate the violence propensities of civilizations throughout history would require extensive research, which is impossible here. What can be done, however, is to identify possible causes of current Muslim group violence, both intra-Islam and extra-Islam, and distinguish between those causes which explain a greater propensity toward group conflict throughout history, if that exists, from those which only explain a propensity at the end of the twentieth century. Six possible causes suggest themselves. Three explain only violence between Muslims and non-Muslims

p. 263

and three explain both that and intra-Islam violence. Three also explain only the contemporary Muslim propensity to violence, while three others explain that and a historical Muslim propensity, if it exists. If that historical propensity, however, does not exist, then its presumed causes that cannot explain a nonexistent historical propensity also presumably do not explain the demonstrated contemporary Muslim propensity to group violence. The latter then can be explained only by twentieth-century causes that did not exist in previous centuries (

Table 10.4

).

Table 10.4 – Possible Causes of Muslim Conflict Propensity

First, the argument is made that Islam has from the start been a religion of the sword and that it glorifies military virtues. Islam originated among “warring Bedouin nomadic tribes” and this “violent origin is stamped in the foundation of Islam. Muhammad himself is remembered as a hard fighter and a skillful military commander.”

[35]

(No one would say this about Christ or Buddha.) The doctrines of Islam, it is argued, dictate war against unbelievers, and when the initial expansion of Islam tapered off, Muslim groups, quite contrary to doctrine, then fought among themselves. The ratio of

fitna

or internal conflicts to jihad shifted drastically in favor of the former. The Koran and other statements of Muslim beliefs contain few prohibitions on violence, and a concept of nonviolence is absent from Muslim doctrine and practice.

Second, from its origin in Arabia, the spread of Islam across northern Africa and much of the middle East and later to central Asia, the Subcontinent, and the Balkans brought Muslims into direct contact with many different peoples, who were conquered and converted, and the legacy of this process remains. In the wake of the Ottoman conquests in the Balkans urban South Slavs often converted to Islam while rural peasants did not, and thus was born the distinction between Muslim Bosnians and Orthodox Serbs. Conversely the expansion of the Russian Empire to the Black Sea, the Caucasus, and Central Asia brought it into continuing conflict for several centuries with a variety of Muslim peoples. The West’s sponsorship, at the height of its power vis-à-vis Islam, of a Jewish homeland in the Middle East laid the basis for ongoing Arab-Israeli antagonism. Muslim and non-Muslim expansion by land thus resulted in Muslims and non-Muslims living in close physical proximity throughout Eurasia. In contrast, the expansion of the West by sea did not usually lead to Western peoples living in territorial proximity to non-Western peoples: these were either

p. 264

subjected to rule from Europe or, except in South Africa, were virtually decimated by Western settlers.

A third possible source of Muslim-non-Muslim conflict involves what one statesman, in reference to his own country, termed the “indigestibility” of Muslims. Indigestibility, however, works both ways: Muslim countries have problems with non-Muslim minorities comparable to those which non-Muslim countries have with Muslim minorities. Even more than Christianity, Islam is an absolutist faith. It merges religion and politics and draws a sharp line between those in the

Dar al-Islam

and those in the

Dar al-harb.

As a result, Confucians, Buddhists, Hindus, Western Christians, and Orthodox Christians have less difficulty adapting to and living with each other than any one of them has in adapting to and living with Muslims. Ethnic Chinese, for instance, are an economically dominant minority in most Southeast Asian countries. They have been successfully assimilated into the societies of Buddhist Thailand and the Catholic Philippines; there are virtually no significant instances of anti-Chinese violence by the majority groups in those countries. In contrast, anti-Chinese riots and/or violence have occurred in Muslim Indonesia and Muslim Malaysia, and the role of the Chinese in those societies remains a sensitive and potentially explosive issue in the way in which it is not in Thailand and the Philippines.

Militarism, indigestibility, and proximity to non-Muslim groups are continuing features of Islam and could explain Muslim conflict propensity throughout history, if that is the case. Three other temporally limited factors could contribute to this propensity in the late twentieth century. One explanation, advanced by Muslims, is that Western imperialism and the subjection of Muslim societies in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries produced an image of Muslim military and economic weakness and hence encourages non-Islamic groups to view Muslims as an attractive target. Muslims are, according to this argument, victims of a widespread anti-Muslim prejudice comparable to the anti-Semitism that historically pervaded Western societies. Muslim groups such as Palestinians, Bosnians, Kashmiris, and Chechens, Akbar Ahmed alleges, are like “Red Indians, depressed groups, shorn of dignity, trapped on reservations converted from their ancestral lands.”

[36]

The Muslim as victim argument, however, does not explain conflicts between Muslim majorities and non-Muslim minorities in countries such as Sudan, Egypt, Iran, and Indonesia.

A more persuasive factor possibly explaining both intra- and extra-Islamic conflict is the absence of one or more core states in Islam. Defenders of Islam often allege that its Western critics believe there is a central, conspiratorial, directing force in Islam mobilizing it and coordinating its actions against the West and others. If the critics believe this, they are wrong. Islam is a source of instability in the world because it lacks a dominant center. States aspiring to be leaders of Islam, such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, and potentially Indonesia, compete for influence in the Muslim world; no one of them is in a

p. 265

strong position to mediate conflicts within Islam; and no one of them is able to act authoritatively on behalf of Islam in dealing with conflicts between Muslim and non-Muslim groups.

Finally, and most important, the demographic explosion in Muslim societies and the availability of large numbers of often unemployed males between the ages of fifteen and thirty is a natural source of instability and violence both within Islam and against non-Muslims. Whatever other causes may be at work, this factor alone would go a long way to explaining Muslim violence in the 1980s and 1990s. The aging of this pig-in-the-python generation by the third decade of the twenty-first century and economic development in Muslim societies, if and as that occurs, could consequently lead to a significant reduction in Muslim violence propensities and hence to a general decline in the frequency and intensity of fault line wars.

Identity: The Rise Of Civilization Consciousness

p. 266

F

ault line wars go through processes of intensification, expansion, containment, interruption, and, rarely, resolution. These processes usually begin sequentially, but they also often overlap and may be repeated. Once started, fault line wars, like other communal conflicts, tend to take on a life of their own and to develop in an action-reaction pattern. Identities which had previously been multiple and casual become focused and hardened; communal conflicts are appropriately termed “identity wars.”

[1]

As violence increases, the initial issues at stake tend to get redefined more exclusively as “us” against “them” and group cohesion and commitment are enhanced. Political leaders expand and deepen their appeals to ethnic and religious loyalties, and civilization consciousness strengthens in relation to other identities. A “hate dynamic” emerges, comparable to the “security dilemma” in international relations, in which mutual fears, distrust, and hatred feed on each other.

[2]

Each side dramatizes and magnifies the distinction between the forces of virtue and the forces of evil and eventually attempts to transform this distinction into the ultimate distinction between the quick and the dead.

As revolutions evolve, moderates, Girondins, and Mensheviks lose out to radicals, Jacobins, and Bolsheviks. A similar process tends to occur in fault line wars. Moderates with more limited goals, such as autonomy rather than independence, do not achieve these goals through negotiation, which almost always initially fails, and get supplemented or supplanted by radicals committed to achieving more extreme goals through violence. In the Moro-Philippine

p. 267

conflict, the principal insurgent group, the Moro National Liberation Front was first supplemented by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, which had a more extreme position, and then by the Abu Sayyaf, which was still more extreme and rejected the cease-fires other groups negotiated with the Philippine government. In Sudan during the 1980s the government adopted increasingly extreme Islamist positions, and in the early 1990s the Christian insurgency split, with a new group, the Southern Sudan Independence Movement, advocating independence rather than simply autonomy. In the ongoing conflict between Israelis and Arabs, as the mainstream Palestine Liberation Organization moved toward negotiations with the Israeli government, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Hamas challenged it for the loyalty of Palestinians. Simultaneously the engagement of the Israeli government in negotiations generated protests and violence from extremist religious groups in Israel. As the Chechen conflict with Russia intensified in 1992-93, the Dudayev government came to be dominated by “the most radical factions of the Chechen nationalists opposed to any accommodation with Moscow, with the more moderate forces pushed into opposition.” In Tajikistan, a similar shift occurred. “As the conflict escalated during 1992, the Tajik nationalist-democratic groups gradually ceded influence to the Islamist groups who were more successful in mobilizing the rural poor and the disaffected urban youth. The Islamist message also became progressively more radicalized as younger leaders emerged to challenge the traditional and more pragmatic religious hierarchy.” “I am shutting the dictionary of diplomacy,” one Tajik leader said. “I am beginning to speak the language of the battlefield, which is the only appropriate language given the situation created by Russia in my homeland.”

[3]

In Bosnia within the Muslim Party of Democratic Action (SDA), the more extreme nationalist faction led by Alija Izetbegovic became more influential than the more tolerant, multiculturally oriented faction led by Haris Silajdzic.

[4]