The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (36 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

In Germany Chancellor Helmut Kohl and other political leaders also expressed concerns about immigration, and in its most important move, the government amended Article XVI of the German constitution guaranteeing asylum to “people persecuted on political grounds” and cut benefits to asylum seekers. In 1992, 438,000 people came to Germany for asylum; in 1994 only 127,000 did. In 1980 Britain had drastically cut back its immigration to about 50,000 a year and hence the issue raised less intense emotions and opposition there than on the continent. Between 1992 and 1994, however, Britain reduced the number of asylum seekers permitted to stay from over 20,000 to less than 10,000. As barriers to movement within the European Union came down, British concerns were in large measure focused on the dangers of non-European migration from the continent. Overall in the mid-1990s Western European countries were moving inexorably toward reducing to a minimum if not totally eliminating immigration from non-European sources.

The immigration issue came to the fore somewhat later in the United States than it did in Europe and did not generate quite the same emotional intensity. The United States has always been a country of immigrants, has so conceived itself, and historically has developed highly successful processes for assimilating newcomers. In addition, in the 1980s and 1990s unemployment was considerably lower in the United States than in Europe, and fear of losing jobs was not a decisive factor shaping attitudes toward immigration. The sources of American immigration were also more varied than in Europe, and thus the fear of being swamped by a single foreign group was less nationally, although real in particular localities. The cultural distance of the two largest migrant groups from the host culture was also less than in Europe: Mexicans are Catholic and Spanish-speaking; Filipinos, Catholic and English-speaking.

Despite these factors, in the quarter century after passage of the 1965 act that permitted greatly increased Asian and Latin American immigration, American public opinion shifted decisively. In 1965 only 33 percent of the public wanted less immigration. In 1977, 42 percent did; in 1986, 49 percent did; and in 1990 and 1993, 61 percent did. Polls in the 1990s consistently show 60 percent or more of the public favoring reduced immigration.

[27]

While economic concerns and economic conditions affect attitudes toward immigration, the steadily rising opposition in good times and bad suggests that culture, crime, and way of life were more important in this change of opinion. “Many, perhaps most, Americans,” one observer commented in 1994, “still see their nation as a European settled country, whose laws are an inheritance from England, whose language is (and should remain) English, whose institutions and public buildings find inspiration in Western classical norms, whose religion has Judeo-Christian roots, and whose greatness initially arose from the Protestant work ethic.” Reflecting these concerns, 55 percent of a sample of the public said

p. 203

they thought immigration was a threat to American culture. While Europeans see the immigration threat as Muslim or Arab, Americans see it as both Latin American and Asian but primarily as Mexican. When asked in 1990 from which countries the United States was admitting too many immigrants, a sample of Americans identified Mexico twice as often as any other, followed in order by Cuba, the Orient (nonspecific), South America and Latin America (nonspecific), Japan, Vietnam, China, and Korea.

[28]

Growing public opposition to immigration in the early 1990s prompted a political reaction comparable to that which occurred in Europe. Given the nature of the American political system, rightist and anti-immigration parties did not gain votes, but anti-immigration publicists and interest groups became more numerous, more active, and more vocal. Much of the resentment focused on the 3.5 million to 4 million illegal immigrants, and politicians responded. As in Europe, the strongest reaction was at the state and local levels, which bear most of the costs of the immigrants. As a result, in 1994 Florida, subsequently joined by six other states, sued the federal government for $884 million a year to cover the education, welfare, law enforcement, and other costs produced by illegal immigrants. In California, the state with the largest number of immigrants absolutely and proportionately, Governor Pete Wilson won public support by urging the denial of public education to children of illegal immigrants, refusing citizenship to U.S.-born children of illegal immigrants, and ending state payments for emergency medical care for illegal immigrants. In November 1994 Californians overwhelmingly approved Proposition 187, denying health, education, and welfare benefits to illegal aliens and their children.

Also in 1994 the Clinton administration, reversing its earlier stance, moved to toughen immigration controls, tighten rules governing political asylum, expand the Immigration and Naturalization Service, strengthen the Border Patrol, and construct physical barriers along the Mexican boundary. In 1995 the Commission on Immigration Reform, authorized by Congress in 1990, recommended reducing yearly legal immigration from over 800,000 to 550,000, giving preference to young children and spouses but not other relatives of current citizens and residents, a provision that “inflamed Asian-American and Hispanic families.”

[29]

Legislation embodying many of the commission’s recommendations and other measures restricting immigration was on its way through Congress in 1995-96. By the mid-1990s immigration had thus become a major political issue in the United States, and in 1996 Patrick Buchanan made opposition to immigration a central plank in his presidential campaign. The United States is following Europe in moving to cut back substantially the entry of non-Westerners into its society.

Can either Europe or the United States stem the migrant tide? France has experienced a significant strand of demographic pessimism, stretching from the searing novel of Jean Raspail in the 1970s to the scholarly analysis of Jean-Claude Chesnais in the 1990s and summed up in the 1991 comments of Pierre Lellouche: “History, proximity and poverty insure that France and Europe are

p. 204

destined to be overwhelmed by people from the failed societies of the south. Europe’s past was white and Judeo-Christian. The future is not.”

[30]

[F08]

The future, however, is not irrevocably determined; nor is any one future permanent. The issue is not whether Europe will be Islamicized or the United States Hispanicized. It is whether Europe and America will become cleft societies encompassing two distinct and largely separate communities from two different civilizations, which in turn depends on the numbers of immigrants and the extent to which they are assimilated into the Western cultures prevailing in Europe and America.

European societies generally either do not want to assimilate immigrants or have great difficulty doing so, and the degree to which Muslim immigrants and their children want to be assimilated is unclear. Hence sustained substantial immigration is likely to produce countries divided into Christian and Muslim communities. This outcome can be avoided to the extent that European governments and peoples are willing to bear the costs of restricting such immigration, which include the direct fiscal costs of anti-immigration measures, the social costs of further alienating existing immigrant communities, and the potential long-term economic costs of labor shortages and lower rates of growth.

The problem of Muslim demographic invasion is, however, likely to weaken as the population growth rates in North African and Middle Eastern societies peak, as they already have in some countries, and begin to decline.

[31]

Insofar as demographic pressure stimulates immigration, Muslim immigration could be much less by 2025. This is not true for sub-Saharan Africa. If economic development occurs and promotes social mobilization in West and Central Africa the incentives and capacities to migrate will increase, and the threat to Europe of “Islamization” will be succeeded by that of “Africanization.” The extent to which this threat materializes will also be significantly influenced by the degree to which African populations are reduced by AIDS and other plagues and the degree to which South Africa attracts immigrants from elsewhere in Africa.

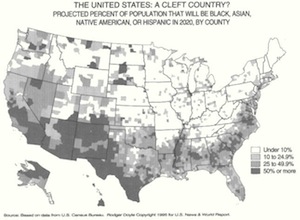

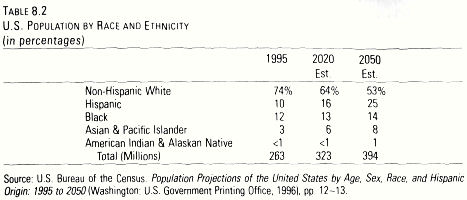

While Muslims pose the immediate problem to Europe, Mexicans pose the problem for the United States. Assuming continuation of current trends and policies, the American population will, as the figures in

Table 8.2

show, change dramatically in the first half of the twenty-first century, becoming almost 50 percent white and 25 percent Hispanic. As in Europe, changes in immigration policy and effective enforcement of anti-immigration measures could change

p. 206

these projections. Even so, the central issue will remain the degree to which Hispanics are assimilated into American society as previous immigrant groups have been. Second and third generation Hispanics face a wide array of incentives and pressures to do so. Mexican immigration, on the other hand, differs in potentially important ways from other immigrations. First, immigrants from Europe or Asia cross oceans; Mexicans walk across a border or wade across a river. This plus the increasing ease of transportation and communication enables them to maintain close contacts and identity with their home communities. Second, Mexican immigrants are concentrated in the southwestern United States and form part of a continuous Mexican society stretching from Yucatan to Colorado (see

Map 8.1

). Third, some evidence suggests that resistance to assimilation is stronger among Mexican migrants than it was with other immigrant groups and that Mexicans tend to retain their Mexican identity, as was evident in the struggle over Proposition 187 in California in 1994. Fourth, the area settled by Mexican migrants was annexed by the United States after it defeated Mexico in the mid-nineteenth century. Mexican economic development will almost certainly generate Mexican revanchist sentiments. In due course, the results of American military expansion in the nineteenth century could be threatened and possibly reversed by Mexican demographic expansion in the twenty-first century.

Map 8.1 – The United States in 2020: A Cleft Country?

Table 8.2 – U.S. Population by Race and Ethnicity

The changing balance of power among civilizations makes it more and more difficult for the West to achieve its goals with respect to weapons proliferation, human rights, immigration, and other issues. To minimize its losses in this situation requires the West to wield skillfully its economic resources as carrots and sticks in dealing with other societies, to bolster its unity and coordinate its policies so as to make it more difficult for other societies to play one Western country off against another, and to promote and exploit differences among non-Western nations. The West’s ability to pursue these strategies will be shaped by the the nature and intensity of its conflicts with the challenger civilizations, on the one hand, and the extent to which it can identify and develop common interests with the swing civilizations, on the other.

Core State And Fault Line Conflicts

p. 207

C

ivilizations are the ultimate human tribes, and the clash of civilizations is tribal conflict on a global scale. In the emerging world, states and groups from two different civilizations may form limited, ad hoc, tactical connections and coalitions to advance their interests against entities from a third civilization or for other shared purposes. Relations between groups from different civilizations however will be almost never close, usually cool, and often hostile. Connections between states of different civilizations inherited from the past, such as Cold War military alliances, are likely to attenuate or evaporate. Hopes for close intercivilizational “partnerships,” such as were once articulated by their leaders for Russia and America, will not be realized. Emerging intercivilizational relations will normally vary from distant to violent, with most falling somewhere in between. In many cases they are likely to approximate the “cold peace” that Boris Yeltsin warned could be the future of relations between Russia and the West. Other intercivilizational relations could approximate a condition of “cold war.” The term

la guerra fria

was coined by thirteenth-century Spaniards to describe their “uneasy coexistence” with Muslims in the Mediterranean, and in the 1990s many saw a “civilizational cold war” again developing between Islam and the West.

[1]

In a world of civilizations, it will not be the only relationship characterized by that term. Cold peace, cold war, trade war, quasi war, uneasy peace, troubled relations, intense rivalry, competitive coexistence, arms races: these phrases are the most probable descriptions of relations between entities from different civilizations. Trust and friendship will be rare.