The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (33 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

“Rather than reinforce power politics as usual,” Lawrence Freedman has observed, “nuclear weapons in fact confirm a tendency towards the fragmentation of the international system in which the erstwhile great powers play a reduced role.” The role of nuclear weapons for the West in the post-Cold War world is thus the opposite of that during the Cold War. Then, as Secretary of Defense Les Aspin pointed out, nuclear weapons compensated for Western conventional inferiority vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. They were “the equalizer.” In the post-Cold War world, however, the United States has “unmatched conventional military power, and it is our potential adversaries who may attain nuclear weapons. We’re the ones who could wind up being the equalizee.”

[3]

It is thus not surprising that Russia has emphasized the role of nuclear weapons in its defense planning and in 1995 arranged to purchase additional intercontinental missiles and bombers from Ukraine. “We are now hearing what we used to say about Russians in 1950s,” one U.S. weapons expert commented. “Now the Russians are saying: ‘We need nuclear weapons to compensate for their conventional superiority.’ ” In a related reversal, during the Cold War the United States, for deterrent purposes, refused to renounce the first use of nuclear weapons. In keeping with the new deterrent function of nuclear weapons in the post-Cold War world, Russia in 1993 in effect renounced the previous Soviet commitment to no-first-use. Simultaneously China, in developing its post-Cold War nuclear strategy of limited deterrence, also began to question and to weaken its 1964 no-first-use commitment.

[4]

As they acquire nuclear and other mass destruction weapons, other core states and regional powers are likely to follow these examples so as to maximize the deterrent effect of their weapons on Western conventional military action against them.

Nuclear weapons also can threaten the West more directly. China and Russia have ballistic missiles that can reach Europe and North America with nuclear warheads. North Korea, Pakistan, and India are expanding the range of their missiles and at some point are also likely to have the capability of targeting the West. In addition, nuclear weapons can be delivered by other means. Military analysts set forth a spectrum of violence from very low intensity warfare, such as terrorism and sporadic guerrilla war, through limited wars to larger wars involving massive conventional forces to nuclear war. Terrorism historically is the weapon of the weak, that is, of those who do not possess conventional military power. Since World War II, nuclear weapons have also been the weapon by which the weak compensate for conventional inferiority. In the past, terrorists could do only limited violence, killing a few people here or destroying a facility there. Massive military forces were required to do massive

p. 188

violence. At some point, however, a few terrorists will be able to produce massive violence and massive destruction. Separately, terrorism and nuclear weapons are the weapons of the non-Western weak. If and when they are combined, the non-Western weak will be strong.

In the post-Cold War world efforts to develop weapons of mass destruction and the means of delivering them have been concentrated in Islamic and Confucian states. Pakistan and probably North Korea have a small number of nuclear weapons or at least the ability to assemble them rapidly and are also developing or acquiring longer range missiles capable of delivering them. Iraq had a significant chemical warfare capability and was making major efforts to acquire biological and nuclear weapons. Iran has an extensive program to develop nuclear weapons and has been expanding its capability for delivering them. In 1988 President Rafsanjani declared that Iranians “must fully equip ourselves both in the offensive and defensive use of chemical, bacteriological, and radiological weapons,” and three years later his vice president told an Islamic conference, “Since Israel continues to possess nuclear weapons, we, the Muslims, must cooperate to produce an atom bomb, regardless of U.N. attempts to prevent proliferation.” In 1992 and 1993 top U.S. intelligence officials said Iran was pursuing the acquisition of nuclear weapons, and in 1995 Secretary of State Warren Christopher bluntly stated, “Today Iran is engaged in a crash effort to develop nuclear weapons.” Other Muslim states reportedly interested in developing nuclear weapons include Libya, Algeria, and Saudi Arabia. “The crescent,” in Ali Mazrui’s colorful phrase, is “over the mushroom cloud,” and can threaten others in addition to the West. Islam could end up “playing nuclear Russian roulette with two other civilizations—with Hinduism in South Asia and with Zionism and politicized Judaism in the Middle East.”

[5]

Weapons proliferation is where the Confucian-Islamic connection has been most extensive and most concrete, with China playing the central role in the transfer of both conventional and nonconventional weapons to many Muslim states. These transfers include: construction of a secret, heavily defended nuclear reactor in the Algerian desert, ostensibly for research but widely believed by Western experts to be capable of producing plutonium; the sale of chemical weapons materials to Libya; the provision of CSS-2 medium-range missiles to Saudi Arabia; the supply of nuclear technology or materials to Iraq, Libya, Syria, and North Korea; and the transfer of large numbers of conventional weapons to Iraq. Supplementing China’s transfers, in the early 1990s North Korea supplied Syria with Scud-C missiles, delivered via Iran, and then the mobile chassis from which to launch them.

[6]

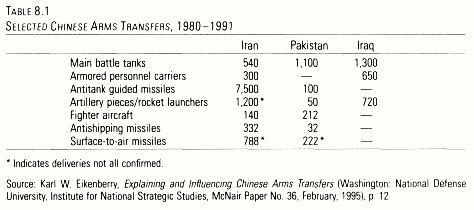

The central buckle in the Confucian-Islamic arms connection has been the relation between China and to a lesser extent North Korea, on the one hand, and Pakistan and Iran, on the other. Between 1980 and 1991 the two chief recipients of Chinese arms were Iran and Pakistan, with Iraq a runner-up.

p. 189

Beginning in the 1970s China and Pakistan developed an extremely intimate military relationship. In 1989 the two countries signed a ten-year memorandum of understanding for military “cooperation in the fields of purchase, joint research and development, joint production, transfer of technology, as well as export to third countries through mutual agreement.” A supplementary agreement providing Chinese credits for Pakistani arms purchases was signed in 1993. As a result, China became “Pakistan’s most reliable and extensive supplier of military hardware, transferring military-related exports of virtually every description and destined for every branch of the Pakistani military.” China also helped Pakistan create production facilities for jet aircraft, tanks, artillery, and missiles. Of much greater significance, China provided essential help to Pakistan in developing its nuclear weapons capability: allegedly furnishing Pakistan with uranium for enrichment, advising on bomb design, and possibly allowing Pakistan to explode a nuclear device at a Chinese test site. China then supplied Pakistan with M-11, 300-kilometer range ballistic missiles that could deliver nuclear weapons, in the process violating a commitment to the United States. In return, China has secured midair refueling technology and Stinger missiles from Pakistan.

[7]

Table 8.1 – Selected Chinese Arms Transfers, 1980-1991

By the 1990s the weapons connections between China and Iran also had become intensive. During the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, China supplied Iran with 22 percent of its arms and in 1989 became its single largest arms supplier. China also actively collaborated in Iran’s openly declared efforts to acquire nuclear weapons. After signing “an initial Sino-Iranian cooperation agreement,” the two countries then agreed in January 1990 to a ten-year understanding on scientific cooperation and military technology transfers. In September 1992 President Rafsanjani accompanied by Iranian nuclear experts visited Pakistan and then went on to China where he signed another agreement for nuclear cooperation, and in February 1993 China agreed to build two 300-MW nuclear reactors in Iran. In keeping with these agreements, China transferred nuclear technology and information to Iran, trained Iranian scientists and engi

p. 190

neers, and provided Iran with a calutron enriching device. In 1995, after sustained U.S. pressure, China agreed to “cancel,” according to the United States, or to “suspend,” according to China, the sale of the two 300-MW reactors. China was also a major supplier of missiles and missile technology to Iran, including in the late 1980s Silkworm missiles delivered through North Korea and “dozens, perhaps hundreds, of missile guidance systems and computerized machine tools” in 1994-1995. China also licensed production in Iran of Chinese surface-to-surface missiles. North Korea supplemented this assistance by shipping Scuds to Iran, aiding Iran to develop its own production facilities, and then agreeing in 1993 to supply Iran with its 600-mile-range Nodong I missile. On the third leg of the triangle, Iran and Pakistan also developed extensive cooperation in the nuclear area, with Pakistan training Iranian scientists, and Pakistan, Iran, and China agreeing in November 1992 to work together on nuclear projects.

[8]

The extensive Chinese help to Pakistan and Iran in developing weapons of mass destruction evidences an extraordinary level of commitment and cooperation between these countries.

As a result of these developments and the potential threats they pose to Western interests, the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction has moved to the top of the West’s security agenda. In 1990, for instance, 59 percent of the American public thought that preventing the spread of nuclear weapons was an important foreign policy goal. In 1994, 82 percent of the public and 90 percent of foreign policy leaders identified it as such. President Clinton highlighted the priority of nonproliferation in September 1993, and in the fall of 1994 declared a “national emergency” to deal with the “unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States” by “the proliferation of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, and the means of delivering such weapons.” In 1991 the CIA created a Nonproliferation Center with a 100-person staff and in December 1993, Secretary of Defense Aspin announced a new Defense Counterproliferation Initiative and the creation of a new position of assistant secretary for nuclear security and counterproliferation.

[9]

During the Cold War the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a classic arms race, developing more and more technologically sophisticated nuclear weapons and delivery vehicles for them. It was a case of buildup versus buildup. In the post-Cold War world the central arms competition is of a different sort. The West’s antagonists are attempting to acquire weapons of mass destruction and the West is attempting to prevent them from doing so. It is not a case of buildup versus buildup but rather of buildup versus hold-down. The size and capabilities of the West’s nuclear arsenal are not, apart from rhetoric, part of the competition. The outcome of an arms race of buildup versus buildup depends on the resources, commitment, and technological competence of the two sides. It is not foreordained. The outcome of a race between buildup and hold-down is more predictable. The hold-down efforts of the West may slow the weapons buildup of other societies, but they will not stop it. The

p. 191

economic and social development of non-Western societies, the commercial incentives for all societies Western and non-Western to make money through the sale of weapons, technology, and expertise, and the political motives of core states and regional powers to protect their local hegemonies, all work to subvert Western hold-down efforts.

The West promotes nonproliferation as reflecting the interests of all nations in international order and stability. Other nations, however, see nonproliferation as serving the interests of Western hegemony. That such is the case is reflected in the differences in concern over proliferation between the West and most particularly the United States, on the one hand, and regional powers whose security would be affected by proliferation, on the other. This was notable with respect to Korea. In 1993 and 1994 the United States worked itself up into a crisis state of mind over the prospect of North Korean nuclear weapons. In November 1993 President Clinton flatly stated, “North Korea cannot be allowed to develop a nuclear bomb. We have to be very firm about it.” Senators, Representatives, and former officials of the Bush administration discussed the possible need for a preemptive attack on North Korean nuclear facilities, U.S. concern over the North Korean program was rooted in considerable measure in its concern with global proliferation; not only would such capability constrain and complicate possible U.S. actions in East Asia, but if North Korea sold its technology and/or weapons it could have comparable effects for the United States in South Asia and the Middle East.

South Korea, on the other hand, viewed the bomb in relation to its regional interests. Many South Koreans saw a North Korean bomb as a

Korean

bomb, one which would never be used against other Koreans but could be used to defend Korean independence and interests against Japan and other potential threats. South Korean civilian officials and military officers explicitly looked forward to a united Korea having that capability. South Korean interests were well served: North Korea would suffer the expense and international obloquy of developing the bomb; South Korea would eventually inherit it; the combination of northern nuclear weapons and southern industrial prowess would enable a unified Korea to assume its appropriate role as a major actor on the East Asian scene. As a result, marked differences existed in the extent to which Washington saw a major crisis existing on the Korean peninsula in 1994 and the absence of any significant sense of crisis in Seoul, creating a “panic gap” between the two capitals. One of the “oddities of the North Korean nuclear standoff, from its start several years ago,” one journalist observed at the height of the “crisis” in June 1994, “is that the sense of crisis increases the farther one is from Korea.” A similar gap between American security interests and those of regional powers occurred in South Asia with the United States being more concerned with nuclear proliferation there than the inhabitants of the region. India and Pakistan each found the other’s nuclear threat easier to accept than American proposals to cap, reduce, or eliminate both threats.

[10]