The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (28 page)

Read The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order Online

Authors: Samuel P. Huntington

Tags: #Current Affairs, #History, #Modern Civilization, #Non-fiction, #Political Science, #Scholarly/Educational, #World Politics

Establishing that line in Europe has been one of the principal challenges confronting the West in the post-Cold War world. During the Cold War Europe as a whole did not exist. With the collapse of communism, however, it became necessary to confront and answer the question: What is Europe? Europe’s boundaries on the north, west, and south are delimited by substantial bodies of water, which to the south coincide with clear differences in culture. But where is Europe’s eastern boundary? Who should be thought of as European and hence as potential members of the European Union, NATO, and comparable organizations?

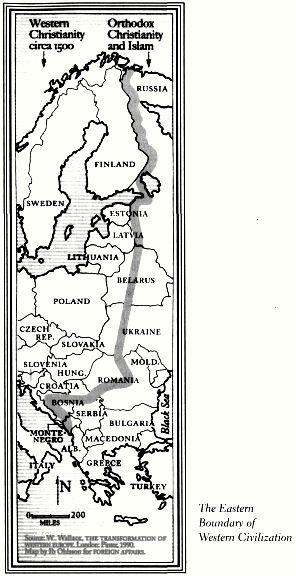

The most compelling and pervasive answer to these questions is provided by the great historical line that has existed for centuries separating Western Christian peoples from Muslim and Orthodox peoples. This line dates back to the division of the Roman Empire in the fourth century and to the creation of the Holy Roman Empire in the tenth century. It has been in roughly its current place for at least five hundred years. Beginning in the north, it runs along what are now the borders between Finland and Russia and the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) and Russia, through western Belarus, through Ukraine separating the Uniate west from the Orthodox east, through Romania between Transylvania with its Catholic Hungarian population and the rest of the country, and through the former Yugoslavia along the border separating Slovenia and Croatia from the other republics. In the Balkans, of course, this line coincides with the historical division between the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires. It is the cultural border of Europe, and in the post-Cold War world it is also the political and economic border of Europe and the West.

Map 7.1 – The Eastern Boundary of Western Civilization

The civilizational paradigm thus provides a clear-cut and compelling answer to the question confronting West Europeans: Where does Europe end? Europe ends where Western Christianity ends and Islam and Orthodoxy begin. This is the answer which West Europeans want to hear, which they overwhelmingly support sotto voce, and which various intellectuals and political leaders have explicitly endorsed. It is necessary, as Michael Howard argued, to recognize the distinction, blurred during the Soviet years, between Central Europe or

Mitteleuropa

and Eastern Europe proper. Central Europe includes “those lands which once formed part of Western Christendom; the old lands of the Hapsburg Empire, Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, together with Poland and the eastern marches of Germany. The term ‘Eastern Europe’ should be reserved for those regions which developed under the aegis of the Orthodox

p. 160

Church: the Black Sea communities of Bulgaria and Romania which only emerged from Ottoman domination in the nineteenth century, and the ‘European’ parts of the Soviet Union.” Western Europe’s first task, he argued, must “be to reabsorb the peoples of Central Europe into our cultural and economic community where they properly belong: to reknit the ties between London, Paris, Rome, Munich, and Leipzig, Warsaw, Prague and Budapest.” A “new fault line” is emerging, Pierre Behar commented two years later, “a basically cultural divide between a Europe marked by western Christianity (Roman Catholic or Protestant), on the one hand, and a Europe marked by eastern Christianity and Islamic traditions, on the other.” A leading Finn similarly saw the crucial division in Europe replacing the Iron Curtain as “the ancient cultural fault line between East and West” which places “the lands of the former Austro-Hungarian empire as well as Poland and the Baltic states” within the Europe of the West and the other East European and Balkan countries outside it. This was, a prominent Englishman agreed, the “great religious divide . . . between the Eastern and Western churches: broadly speaking, between those peoples who received their Christianity from Rome directly or through Celtic or German intermediaries, and those in the East and Southeast to whom it came through Constantinople (Byzantium).”

[2]

People in Central Europe also emphasize the significance of this dividing line. The countries that have made significant progress in divesting themselves of the Communist legacies and moving toward democratic politics and market economies are separated from those which have not by “the line dividing Catholicism and Protestantism, on the one hand, from Orthodoxy, on the other.” Centuries ago, the president of Lithuania argued, Lithuanians had to choose between “two civilizations” and “opted for the Latin world, converted to Roman Catholicism and chose a form of state organization founded on law.” In similar terms, Poles say they have been part of the West since their choice in the tenth century of Latin Christianity against Byzantium.

[3]

People from Eastern European Orthodox countries, in contrast, view with ambivalence the new emphasis on this cultural fault line. Bulgarians and Romanians see the great advantages of being part of the West and being incorporated into its institutions; but they also identify with their own Orthodox tradition and, on the part of the Bulgarians, their historically close association with Russia and Byzantium.

The identification of Europe with Western Christendom provides a clear criterion for the admission of new members to Western organizations. The European Union is the West’s primary entity in Europe and the expansion of its membership resumed in 1994 with the admission of culturally Western Austria, Finland, and Sweden. In the spring of 1994 the Union provisionally decided to exclude from membership all former Soviet republics except the Baltic states. It also signed “association agreements” with the four Central European states (Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic, and Slovakia) and two

p. 161

Eastern European ones (Romania, Bulgaria). None of these states, however, is likely to become a full member of the EU until sometime in the twenty-first century, and the Central European states will undoubtedly achieve that status before Romania and Bulgaria, if, indeed, the latter ever do. Meanwhile eventual membership for the Baltic states and Slovenia looks promising, while the applications of Muslim Turkey, too-small Malta, and Orthodox Cyprus were still pending in 1995. In the expansion of EU membership, preference clearly goes to those states which are culturally Western and which also tend to be economically more developed. If this criterion were applied, the Visegrad states (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary), the Baltic republics, Slovenia, Croatia, and Malta would eventually become EU members and the Union would be coextensive with Western civilization as it has historically existed in Europe.

The logic of civilizations dictates a similar outcome concerning the expansion of NATO. The Cold War began with the extension of Soviet political and military control into Central Europe. The United States and Western European countries formed NATO to deter and, if necessary, defeat further Soviet aggression. In the post-Cold War world, NATO is the security organization of Western civilization. With the Cold War over, NATO has one central and compelling purpose: to insure that it remains over by preventing the reimposition of Russian political and military control in Central Europe. As the West’s security organization NATO is appropriately open to membership by Western countries which wish to join and which meet basic requirements in terms of military competence, political democracy, and civilian control of the military.

American policy toward post-Cold War European security arrangements initially embodied a more universalistic approach, embodied in the Partnership for Peace, which would be open generally to European and, indeed, Eurasian countries. This approach also emphasized the role of the Organization on Security and Cooperation in Europe. It was reflected in the remarks of President Clinton when he visited Europe in January 1994: “Freedom’s boundaries now should be defined by new behavior, not by old history. I say to all . . . who would draw a new line in Europe: we should not foreclose the possibility of the best future for Europe—democracy everywhere, market economies everywhere, countries cooperating for mutual security everywhere. We must guard against a lesser outcome.” A year later, however, the administration had come to recognize the significance of boundaries defined by “old history” and had come to accept a “lesser outcome” reflecting the realities of civilizational differences. The administration moved actively to develop the criteria and a schedule for the expansion of NATO membership, first to Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, then to Slovenia, and later probably to the Baltic republics.

Russia vigorously opposed any NATO expansion, with those Russians who were presumably more liberal and pro-Western arguing that expansion would

p. 162

greatly strengthen nationalist and anti-Western political forces in Russia. NATO expansion limited to countries historically part of Western Christendom, however, also guarantees to Russia that it would exclude Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, Belarus, and Ukraine as long as Ukraine remained united. NATO expansion limited to Western states would also underline Russia’s role as the core state of a separate, Orthodox civilization, and hence a country which should be responsible for order within and along the boundaries of Orthodoxy.

The usefulness of differentiating among countries in terms of civilization is manifest with respect to the Baltic republics. They are the only former Soviet republics which are clearly Western in terms of their history, culture, and religion, and their fate has consistently been a major concern of the West. The United States never formally recognized their incorporation into the Soviet Union, supported their move to independence as the Soviet Union was collapsing, and insisted that the Russians adhere to the agreed-on schedule for the removal of their troops from the republics. The message to the Russians has been that they must recognize that the Baltics are outside whatever sphere of influence they may wish to establish with respect to other former Soviet republics. This achievement by the Clinton administration was, as Sweden’s prime minister said, “one of its most important contributions to European security and stability” and helped Russian democrats by establishing that any revanchist designs by extreme Russian nationalists were futile in the face of the explicit Western commitment to the republics.

[4]

While much attention has been devoted to the expansion of the European Union and NATO, the cultural reconfiguration of these organizations also raises the issue of their possible contraction. One non-Western country, Greece, is a member of both organizations, and another, Turkey, is a member of NATO and an applicant for Union membership. These relationships were products of the Cold War. Do they have any place in the post-Cold War world of civilizations?

Turkey’s full membership in the European Union is problematic and its membership in NATO has been attacked by the Welfare Party. Turkey is, however, likely to remain in NATO unless the Welfare Party scores a resounding electoral victory or Turkey otherwise consciously rejects its Ataturk heritage and redefines itself as a leader of Islam. This is conceivable and might be desirable for Turkey but also is unlikely in the near future. Whatever its role in NATO, Turkey will increasingly pursue its own distinctive interests with respect to the Balkans, the Arab world, and Central Asia.

Greece is not part of Western civilization, but it was the home of Classical civilization which was an important source of Western civilization. In their opposition to the Turks, Greeks historically have considered themselves spear-carriers of Christianity. Unlike Serbs, Romanians, or Bulgarians, their history has been intimately entwined with that of the West. Yet Greece is also an anomaly, the Orthodox outsider in Western organizations. It has never been an

p. 163

easy member of either the EU or NATO and has had difficulty adapting itself to the principles and mores of both. From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s it was ruled by a military junta, and could not join the European Community until it shifted to democracy. Its leaders often seemed to go out of their way to deviate from Western norms and to antagonize Western governments. It was poorer than other Community and NATO members and often pursued economic policies that seemed to flout the standards prevailing in Brussels. Its behavior as president of the EU’s Council in 1994 exasperated other members, and Western European officials privately label its membership a mistake.

In the post-Cold War world, Greece’s policies have increasingly deviated from those of the West. Its blockade of Macedonia was strenuously opposed by Western governments and resulted in the European Commission seeking an injunction against Greece in the European Court of Justice. With respect to the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia, Greece separated itself from the policies pursued by the principal Western powers, actively supported the Serbs, and blatantly violated the U.N. sanctions levied against them. With the end of the Soviet Union and the communist threat, Greece has mutual interests with Russia in opposition to their common enemy, Turkey. It has permitted Russia to establish a significant presence in Greek Cyprus, and as a result of “their shared Eastern Orthodox religion,” the Greek Cypriots have welcomed both Russians and Serbs to the island.

[5]

In 1995 some two thousand Russian-owned businesses were operating in Cyprus; Russian and Serbo-Croatian newspapers were published there; and the Greek Cypriot government was purchasing major supplies of arms from Russia. Greece also explored with Russia the possibility of bringing oil from the Caucasus and Central Asia to the Mediterranean through a Bulgarian-Greek pipeline bypassing Turkey and other Muslim countries. Overall Greek foreign policies have assumed a heavily Orthodox orientation. Greece will undoubtedly remain a formal member of NATO and the European Union. As the process of cultural reconfiguration intensifies, however, those memberships also undoubtedly will become more tenuous, less meaningful, and more difficult for the parties involved. The Cold War antagonist of the Soviet Union is evolving into the post-Cold War ally of Russia.