The Act of Creation (4 page)

Read The Act of Creation Online

Authors: Arthur Koestler

Let us return to reasoning skills. Mathematical reasoning is governed

by specific rules of the game -- multiplication, differentiation,

integration, etc. Verbal reasoning, too, is subject to a variety of

specific codes: we can discuss Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo 'in terms

of' (a) historic significance, (b) military strategy, (c) the condition

of his liver, (d) the constellation of the planets. We can call these

'frames of reference' or 'universes of discourse' or 'associative

contexts' -- expressions which I shall frequently use to avoid monotonous

repetitions of the word 'matrix'. The jokes in the previous section can

all be described as universes of discourse colliding, frames getting

entangled, or contexts getting confused. But we must remember that each

of these expressions refers to specific patterns of activity which,

though flexible, are governed by sets of fixed rules.

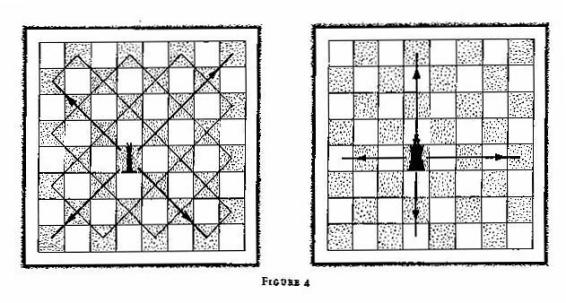

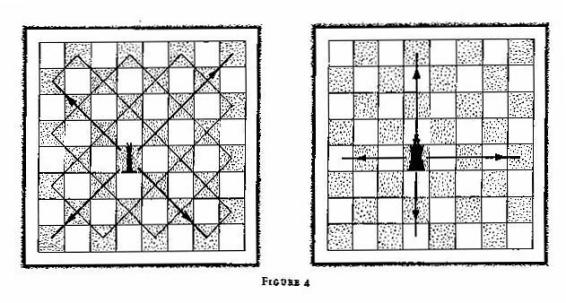

A chess player looking at an empty board with a single bishop on it does

not see the board as a uniform mosaic of black and white squares, but

as a kind of magnetic field with lines of force indicating the bishops'

possible moves: the board has become patterned, as in Fig. 4a; Fig. 4b

shows the pattern of the rook.

When one thinks of 'matrices' and 'codes' it is sometimes helpful to

When one thinks of 'matrices' and 'codes' it is sometimes helpful to

bear these figures in mind. The "matrix" is the pattern before you,

representing the ensemble of permissible moves. The "code" which governs

the matrix can be put into simple mathematical equations which contain

the essence of the pattern in a compressed, 'coded' form; or it can be

expressed by the word 'diagonals'. The code is the fixed, invariable

factor in a skill or habit; the matrix its variable aspect. The two words

do not refer to different entities, they refer to different "aspects" of

the same activity. When you sit in front of the chessboard your "code"

is the rule of the game determining which moves are permitted, your

"matrix" is the total of possible choices before you. Lastly, the choice

of the actual move among the variety of permissible moves is a matter of

"strategy," guided by the lie of the land -- the 'environment' of other

chessmen on the board. We have seen that comic effects are produced

by the sudden clash of incompatible matrices: to the experienced chess

player a rook moving bishopwise is decidedly 'funny'.

Consider a pianist playing a set-piece which he has learned by heart.

He has incomparably more scope for 'strategy' (tempo, rhythm, phrasing)

than the spider spinning its web. A musician transposing a tune into

a different key, or improvising variations of it, enjoys even greater

freedom; but he too is still bound by the codes of the diatonic or

chromatic scale. Matrices vary in flexibility from reflexes and more

or less automatized routines which allow but a few strategic choices,

to skills of almost unlimited variety; but all coherent thinking and

behaviour is subject to some specifiable code of rules to which its

character of coherence is due -- even though the code functions partly

or entirely on umconscious levels of the mind, as it generally does. A

bar-pianist can perform in his sleep or while conversing with the barmaid;

he has handed over control to the automatic pilot, as it were.

Hidden Persuaders

Everybody can ride a bicycle, but nobody knows how it is done. Not even

engineers and bicycle manufacturers know the formula for the correct

method of counteracting the tendency to fall by turning the handlebars

so that 'for a given angle of unbalance the curvature of each winding is

inversely proportional to the square of the speed at which the cyclist is

proceeding'. [6] The cyclist obeys a code of rules which is specifiable,

but which he cannot specify; he could write on his number-plate Pascal's

motto:

Le coeur a ses raisons que la raison ne connaît point.

Or, to put it in a more abstract way:

but also to the skill of perceiving the world around us in a coherent

and meaningful manner. Hold your left hand six inches, the other twelve

inches, away from your eyes; they will look about the same size, although

the retinal image of the left is twice the size of the right. Trace

the contours of your face with a soapy finger on the bathroom mirror

(it is easily done by closing one eye). There is a shock waiting: the

image which looked life-size has shrunk to half-size, like a headhunter's

trophy. A person walking away does not seem to become a dwarf -- as he

should; a black glove looks just as black in the sunlight as in shadow

-- though it should not; when a coin is held before the eyes in a tilted

position its retinal projection will be a more or less flattened ellipse;

yet we see it as a circle, because we

know

it to be a circle; and it

takes some effort to see it actually as a squashed oval shape. Seeing is

believing, as the saying goes, but the reverse is also true: knowing is

seeing. 'Even the most elementary perceptions', wrote Bartlett, [7] 'have

the character of inferential constructions.' But the inferential process,

which controls perception, again works unconsciously. Seeing is a skill,

part innate, part acquired in early infancy.* The selective codes in this

case operate on the input, not on the output. The stimuli impinging on the

senses provide only the raw material of our conscious experience -- the

'blooming, buzzing confusion' of William James; before reaching awareness

the input is filtered, processed, distorted, interpreted, and reorganized

in a series of relay stations at various levels of the nervous system;

but the processing itself is not experienced by the person, and the

rules of the game according to which the controls work are unknown to him.

The examples I mentioned refer to the so-called 'visual constancies'

which enable us to recognize that the size, brightness, shape of objects

remain the same even though their retinal image changes all the time;

and to 'make sense' out of our sensations. They are shared by all people

with normal vision, and provide the basic structure on which more personal

'frames of perception' can be built. An apple looks different to Picasso

and to the greengrocer because their visual matrices are different.

Let me return once more to verbal thinking. When a person discusses,

say, the problem of capital punishment he may do so 'in terms of'

social utility or religious morality or psychopathology. Each of these

universes of discourse is governed by a complex set of rules, some of

which operate on conscious, others on unconscious levels. The latter are

axiomatic beliefs and prejudices which are taken for granted and implied

in the code. Further implied, hidden in the space between the words, are

the rules of grammar and syntax. These have mostly been learned not from

textbooks but 'by ear', as a young gypsy learns to fiddle without knowing

musical notation. Thus when one is engaged in ordinary conversation, not

only do the codes of grammar and syntax, of courtesy and common-or-garden

logic function unconsciously, but even if consciously bent on doing so

we would find it extremely difficult to define these rules which define

our thinking. For doing that we need the services of specialists -- the

semanticists and logicians of language. In other words, there is less

difference between the routines of thinking and bicycle-riding than our

self-esteem would make us believe. Both are governed by implicit codes

of which we are only dimly aware, and which we are unable to specify.*

Habit and Originality

Without these indispensable codes we would fall off the bicycle, and

thought would lose its coherence -- as it does when the codes of normal

reasoning are suspended while we dream. On the other hand, thinking which

remains confined to a single matrix has its obvious limitations. It is

the exercise of a more or less flexible skill, which can perform tasks

only of a kind already encountered in past experience; it is not capable

of original, creative achievement.

We learn by assimilating experiences and grouping them into ordered

schemata, into stable patterns of unity in variety. They enable us to cope

with events and situations by applying the rules of the game appropriate

to them. The matrices which pattern our perceptions, thoughts, and

activities are condensations of learning into habit. The process starts

in infancy and continues to senility; the hierarchy of flexible matrices

with fixed codes -- from those which govern the breathing of his cells,

to those which determine the pattern of his signature, constitute that

creature of many-layered habits whom we call John Brown. When the Duke

of Wellington was asked whether he agreed that habit was man's second

nature he exclaimed: 'Second nature? It's ten times nature!'

Habits have varying degrees of flexibility; if often repeated under

unchanging conditions, in a monotonous environment, they tend to

become rigid and automarized. But even an elastic strait-jacket is

still a strait-jacket if the patient has no possibility of getting out

of it. Behaviourism, the dominant school in contemporary psychology, is

inclined to take a view of man which reduces him to the station of that

patient, and the human condition to that of a conditioned automaton. I

believe that view to be depressingly true up to a point. The argument

of this book starts at the point where, I believe, it ceases to be true.

There are two ways of escaping our more or less automatized routines

of thinking and behaving. The first, of course, is the plunge into

dreaming or dream-like states, when the codes of rational thinking are

suspended. The other way is also an escape -- from boredom, stagnation,

intellectual predicaments, and emotional frustration -- but an escape

in the opposite direction; it is signalled by the spontaneous flash of

insight which shows a familiar situation or event in a new light, and

elicits a new response to it. The bisociative act connects previously

unconnected matrices of experience; it makes us 'understand what it is to

be awake, to be living on several planes at once' (to quote T. S. Eliot,

somewhat out of context).

The first way of escape is a regression to earlier, more primitive levels

of ideation, exemplified in the language of the dream; the second an

ascent to a new, more complex level of mental evolution. Though seemingly

opposed, the two processes will turn out to he intimately related.

Man and Machine

When two independent matrices of perception or reasoning interact

with each other the result (as I hope to show) is either a

collision

ending in laughter, or their

fusion

in a new intellectual synthesis,

or their

confrontation

in an aesthetic experience. The bisociative

patterns found in any domain of creative activity are tri-valent:

that is to say, the same pair of matrices can produce comic, tragic,

or intellectually challenging effects.

Let me take as a first example 'man' and 'machine'. A favourite trick of

the coarser type of humour is to exploit the contrast between these two

frames of reference (or between the related pair 'mind' and 'matter'). The

dignified schoolmaster lowering himself into a rickety chair and crashing

to the floor is perceived simultaneously in two incompatible contexts:

authority is debunked by gravity. The savage, wistfully addressing the

carved totem figure -- 'Don't be so proud, I know you from a plum-tree' --

expresses the same idea: hubris of mind, earthy materiality of body. The

variations on this theme are inexhaustible: the person slipping on a

banana skin; the sergeant-major attacked by diarrhoea; Hamlet getting

the hiccoughs; soldiers marching like automata; the pedant behaving

like a mechanical robot; the absent-minded don boiling his watch while

clutching the egg, like a machine obeying the wrong switch. Fate keeps

playing practical jokes to deflate the victim's dignity, intellect, or

conceit by demonstrating his dependence on coarse bodily functions and

physical laws -- by degrading him to an automaton. The same purpose is

served by the reverse technique of making artefacts behave like humans:

Punch and Judy, Jack-in-the-Box, gadgets playing tricks on their masters,

hats in a gust of wind escaping the pursuer as if with calculated malice.

In Henri Bergson's book on the problem of laughter, this dualism of

subtle mind and inert matter ('the mechanical encrusted on the living')

is made to serve as an explanation of

all

forms of the comic; whereas

in the present theory it applies to only one variant of it among many

others. Surprisingly, Bergson failed to see that each of the examples

just mentioned can be convened from a comic into a tragic or purely

intellectual experience, based on the same logical pattern -- i.e. on

the same pair of bisociated matrices -- by a simple change of emotional

climate. The fat man slipping and crashing on the icy pavement will be

either a comic or a tragic figure according to whether the spectator's

attitude is dominated by malice or pity: a callous schoolboy will laugh

at the spectade, a sentimental old lady may be inclined to weep. But

in between these two there is the emotionally balanced attitude of the

physician who happens to pass the scene of the mishap, who may feel both

amusement and compassion, but whose primary concern is to find out the

nature of the injury. Thus the victim of the crash may be seated in any

of the three panels of the triptych. Don Quixote gradually changes from

a comic into a puzzling figure if, instead of relishing his delusions

with arrogant condescension, I become interested in their psychological

causes; and he changes into a tragic figure as detached curiosity turns

into sympathetic identification -- as I recognize in the sad knight my

brother-in-arms in the fight against windmills. The stock characters

in the farce -- the cuckold, the miser, the stutterer, the hunchback,

the foreigner -- appear as comic, intellectually challenging, or tragic

figures according to the different emotional attitudes which they arouse

in spectators of different mental age, culture, or mood.

The 'mechanical encrusted on the living' symbolizes the contrast between

man's spiritual aspirations and his all-too-solid flesh subject to

the laws of physics and chemistry. The practical joker and the clown

specialize in tricks which exploit the mechanical forces of gravity

and inertia to deflate his humanity. But Icarus, too, like the dinner

guest whose chair collapsed, is the victim of a practical joke -- the

gods, instead of breaking the legs of his chair, have melted away his

wings. The second appeals to loftier emotions than the first, but the

logical structure of the two situations and their message is the same:

whatever you fancy yourself to be you are subject to the inverse square

law like any other lump of clay. In one case it is a comic, in the other

a tragic message. The difference is due to the different character of the

emotions involved (malice in the first case, compassionate admiration

in the second); but also to the fact that in the first case the two

frames of reference collide, exploding the tension, while in the second

they remain juxtaposed in a tragic confrontation, and the tension ebbs

away in a slow catharsis. The third alternative is the reconciliation

and synthesis of the two matrices; its effect is neither laughter,

nor tears, but the arousal of curiosity: just

how

is the mechanical

encrusted on the living? How much acceleration can the organism stand,

and how does zero gravity effect it?

According to Bergson, the main sources of the comic are the mechanical

attributes of inertia, rigidity, and repetitiveness impinging on life;

among his favourite examples are the man-automaton, the puppet on strings,

Jack-in-the-Box, etc. However, if rigidity contrasted with organic

suppleness were laughable in itself, Egyptian statues and Byzantine

mosaics would be the best jokes ever invented. If automatic repetativeness

in human behaviour were a necessary and sufficient condition of the

comic, there would be no more amusing spectacle thau an epileptic fit;

and if we wanted a good laugh we would merely have to feel a person's

pulse or listen to his heart-beat, with its monotonous tick-tack. If

'we laugh each time a person gives us the impression of being a thing'

[8] there would be nothing more funny than a corpse.

In fact, every one of Bergson's examples of the comic can be transposed,

along a horizontal line as it were, across the triptych, into the

panels of science and art. His 'homme-automate', man and artefact at

the same time, has its lyric counterpart in Galatea -- the ivory statue

which Pygmalion made, Aphrodite brought to life, and Shaw returned

to the comic domain. It has its tragic counterpart in the legends of

Faust's Homunculus, the Golem of Prague, the monsters of Frankenstein;

its origins reach back to Jehovah manufacturing Adam out of 'adamåh',

the Hebrew word for earth. The reverse transformation -- life into

mechanism -- has equally rich varieties: the pedant whom enslavement to

habit has reduced to an automaton is comic because we despise him; the

compulsion-neurotic is not, because we are puzzled and try to understand

him; the catatonic patient, frozen into a statue, is tragic because we

pity him. And so again back to mythology: Lot's wife turned into a pillar

of salt, Narcissus into a flower, the poor nymph Echo wasting away until

nothing is left but her voice, and her bones changed into rocks.

In the middle panel of the triptych the 'homme-automate' is the

focal, or rather bi-focal, concept of all sciences of life. From their

inception they treated, as the practical joker does, man as both mind

and machine. The Pythagoreans regarded the body as a musical instrument

whose soul-strings must have the right tension, and we still unwittingly

refer to our mortal frame as a kind of stringed guitar when we speak of

'muscle

tone

', or describe John as 'good tempered'. The same bifocal

view is reflected in the four Hippocratic 'humours' -- which were both

liquids of the body and moods of the spirit; and 'spiritus' itself is,

like 'pneuma', ambiguous, meaning also breath. The concept of 'catharsis'

applied, and still does, to the purgation of either the mind or the

bowels. Yet if I were to speak earnestly of halitosis of the soul, or

of laxatives to the mind, or call an outburst of temper a humourrhage,

it would sound ludicrous, because I would make the implicit ambiguities

explicit for the purpose of maliciously contrasting them; I would tear

asunder two frames of reference that our Greek forbears had managed to

integrate, however tentatively, into a unified, psychosomatic view which

our language still reflects.

In modern science it has become accepted usage to speak of the

'mechanisms' of digestion, perception, learning, and cognition, etc.,

and to lay increasing or exclusive stress on the automaton aspect of the

'homme-automate'. The mechanistic trend in physiology reached its symbolic

culmination at the beginning of the century in the slogan 'Man a machine'

-- the programmatic title of a once famous book by Jacques Loeb; it was

taken over by behaviouristic psychology, which has been prominent in

the Anglo-Saxon countries for half a century. Even a genial naturalist

like Konrad Lorenz, whose

King Solomon's Ring

has delighted millions,

felt impelled to proclaim that to regard Newton and Darwin as automata

was the only permissible view for 'the inductive research worker who

does not believe in miracles'. [9] It all depends, of course, on what

one's definition of a miracle is: Galileo, the ideal of all 'inductive

research workers', rejected Kepler's theory that the tides were due to

the moon's attraction as an 'occult fancy'. [10] The intellectual climate

created by these attitudes has been summed up by Cyril Burt, writing

about 'The Concept of Consciousness' (which behaviourists have banned,

as another 'occult fancy', from the vocabulary of science): 'The result,

as a cynical onlooker might be tempted to say, is that psychology, having

first bargained away its soul and then gone out of its mind, seems now,

as it faces an untimely end, to have lost all consciousness.' [11]

I have dwelt at some length on Bergson's favourite example of the comic,

because of its relevance to one of the leitmotifs of this book. The

man-machine duality has been epitomized in a laconic sentence -- 'man

consists of ninety per cent water and ten per cent minerals' -- which one

can regard, according to taste, as comic, intellectually challenging, or

tragic. In the first case one has only to think of a caricature showing a

fat man under the African sun melting away into a puddle; in the second,

of the 'inductive research worker' bent over his test-tube; in the third,

of a handful of dust.

Other examples of Bergson's man-automaton need be mentioned only

briefly. The puppet play in its naïve Punch and Judy version is

comic

;

the sophisticated marionette theatre is a traditional form of

art

;

life-imitating contraptions are used in various branches of

science

and technology: from the dummy figures of dressmakers to the anatomical

models in medical schools; from the artificial limbs of the orthopaedist

to robots imitating the working of the nervous system (such as Grey

Walter's electronic tortoises). In the

metaphorical

sense, the

puppet on strings is a timeless symbol, either comic or tragic, of man

as a plaything of destiny -- whether he is jerked about by the gods

or suspended on his own chromosomes and glands. In the neutral zone

between Comedy and tragedy, philosophers have been tireless in their

efforts to reconcile the two conflicting aspects of the human puppet:

his experience of free will and moral responsibility on the one hand;

the strings of determinism, religious or scientific, on the other.

by specific rules of the game -- multiplication, differentiation,

integration, etc. Verbal reasoning, too, is subject to a variety of

specific codes: we can discuss Napoleon's defeat at Waterloo 'in terms

of' (a) historic significance, (b) military strategy, (c) the condition

of his liver, (d) the constellation of the planets. We can call these

'frames of reference' or 'universes of discourse' or 'associative

contexts' -- expressions which I shall frequently use to avoid monotonous

repetitions of the word 'matrix'. The jokes in the previous section can

all be described as universes of discourse colliding, frames getting

entangled, or contexts getting confused. But we must remember that each

of these expressions refers to specific patterns of activity which,

though flexible, are governed by sets of fixed rules.

A chess player looking at an empty board with a single bishop on it does

not see the board as a uniform mosaic of black and white squares, but

as a kind of magnetic field with lines of force indicating the bishops'

possible moves: the board has become patterned, as in Fig. 4a; Fig. 4b

shows the pattern of the rook.

bear these figures in mind. The "matrix" is the pattern before you,

representing the ensemble of permissible moves. The "code" which governs

the matrix can be put into simple mathematical equations which contain

the essence of the pattern in a compressed, 'coded' form; or it can be

expressed by the word 'diagonals'. The code is the fixed, invariable

factor in a skill or habit; the matrix its variable aspect. The two words

do not refer to different entities, they refer to different "aspects" of

the same activity. When you sit in front of the chessboard your "code"

is the rule of the game determining which moves are permitted, your

"matrix" is the total of possible choices before you. Lastly, the choice

of the actual move among the variety of permissible moves is a matter of

"strategy," guided by the lie of the land -- the 'environment' of other

chessmen on the board. We have seen that comic effects are produced

by the sudden clash of incompatible matrices: to the experienced chess

player a rook moving bishopwise is decidedly 'funny'.

Consider a pianist playing a set-piece which he has learned by heart.

He has incomparably more scope for 'strategy' (tempo, rhythm, phrasing)

than the spider spinning its web. A musician transposing a tune into

a different key, or improvising variations of it, enjoys even greater

freedom; but he too is still bound by the codes of the diatonic or

chromatic scale. Matrices vary in flexibility from reflexes and more

or less automatized routines which allow but a few strategic choices,

to skills of almost unlimited variety; but all coherent thinking and

behaviour is subject to some specifiable code of rules to which its

character of coherence is due -- even though the code functions partly

or entirely on umconscious levels of the mind, as it generally does. A

bar-pianist can perform in his sleep or while conversing with the barmaid;

he has handed over control to the automatic pilot, as it were.

Hidden Persuaders

Everybody can ride a bicycle, but nobody knows how it is done. Not even

engineers and bicycle manufacturers know the formula for the correct

method of counteracting the tendency to fall by turning the handlebars

so that 'for a given angle of unbalance the curvature of each winding is

inversely proportional to the square of the speed at which the cyclist is

proceeding'. [6] The cyclist obeys a code of rules which is specifiable,

but which he cannot specify; he could write on his number-plate Pascal's

motto:

Le coeur a ses raisons que la raison ne connaît point.

Or, to put it in a more abstract way:

The controls of a skilled activity generally function below the levelThis applies not only to our visceral activities and muscular skills,

of consciousness on which that activity takes place. The code is a

hidden persuader.

but also to the skill of perceiving the world around us in a coherent

and meaningful manner. Hold your left hand six inches, the other twelve

inches, away from your eyes; they will look about the same size, although

the retinal image of the left is twice the size of the right. Trace

the contours of your face with a soapy finger on the bathroom mirror

(it is easily done by closing one eye). There is a shock waiting: the

image which looked life-size has shrunk to half-size, like a headhunter's

trophy. A person walking away does not seem to become a dwarf -- as he

should; a black glove looks just as black in the sunlight as in shadow

-- though it should not; when a coin is held before the eyes in a tilted

position its retinal projection will be a more or less flattened ellipse;

yet we see it as a circle, because we

know

it to be a circle; and it

takes some effort to see it actually as a squashed oval shape. Seeing is

believing, as the saying goes, but the reverse is also true: knowing is

seeing. 'Even the most elementary perceptions', wrote Bartlett, [7] 'have

the character of inferential constructions.' But the inferential process,

which controls perception, again works unconsciously. Seeing is a skill,

part innate, part acquired in early infancy.* The selective codes in this

case operate on the input, not on the output. The stimuli impinging on the

senses provide only the raw material of our conscious experience -- the

'blooming, buzzing confusion' of William James; before reaching awareness

the input is filtered, processed, distorted, interpreted, and reorganized

in a series of relay stations at various levels of the nervous system;

but the processing itself is not experienced by the person, and the

rules of the game according to which the controls work are unknown to him.

The examples I mentioned refer to the so-called 'visual constancies'

which enable us to recognize that the size, brightness, shape of objects

remain the same even though their retinal image changes all the time;

and to 'make sense' out of our sensations. They are shared by all people

with normal vision, and provide the basic structure on which more personal

'frames of perception' can be built. An apple looks different to Picasso

and to the greengrocer because their visual matrices are different.

Let me return once more to verbal thinking. When a person discusses,

say, the problem of capital punishment he may do so 'in terms of'

social utility or religious morality or psychopathology. Each of these

universes of discourse is governed by a complex set of rules, some of

which operate on conscious, others on unconscious levels. The latter are

axiomatic beliefs and prejudices which are taken for granted and implied

in the code. Further implied, hidden in the space between the words, are

the rules of grammar and syntax. These have mostly been learned not from

textbooks but 'by ear', as a young gypsy learns to fiddle without knowing

musical notation. Thus when one is engaged in ordinary conversation, not

only do the codes of grammar and syntax, of courtesy and common-or-garden

logic function unconsciously, but even if consciously bent on doing so

we would find it extremely difficult to define these rules which define

our thinking. For doing that we need the services of specialists -- the

semanticists and logicians of language. In other words, there is less

difference between the routines of thinking and bicycle-riding than our

self-esteem would make us believe. Both are governed by implicit codes

of which we are only dimly aware, and which we are unable to specify.*

Habit and Originality

Without these indispensable codes we would fall off the bicycle, and

thought would lose its coherence -- as it does when the codes of normal

reasoning are suspended while we dream. On the other hand, thinking which

remains confined to a single matrix has its obvious limitations. It is

the exercise of a more or less flexible skill, which can perform tasks

only of a kind already encountered in past experience; it is not capable

of original, creative achievement.

We learn by assimilating experiences and grouping them into ordered

schemata, into stable patterns of unity in variety. They enable us to cope

with events and situations by applying the rules of the game appropriate

to them. The matrices which pattern our perceptions, thoughts, and

activities are condensations of learning into habit. The process starts

in infancy and continues to senility; the hierarchy of flexible matrices

with fixed codes -- from those which govern the breathing of his cells,

to those which determine the pattern of his signature, constitute that

creature of many-layered habits whom we call John Brown. When the Duke

of Wellington was asked whether he agreed that habit was man's second

nature he exclaimed: 'Second nature? It's ten times nature!'

Habits have varying degrees of flexibility; if often repeated under

unchanging conditions, in a monotonous environment, they tend to

become rigid and automarized. But even an elastic strait-jacket is

still a strait-jacket if the patient has no possibility of getting out

of it. Behaviourism, the dominant school in contemporary psychology, is

inclined to take a view of man which reduces him to the station of that

patient, and the human condition to that of a conditioned automaton. I

believe that view to be depressingly true up to a point. The argument

of this book starts at the point where, I believe, it ceases to be true.

There are two ways of escaping our more or less automatized routines

of thinking and behaving. The first, of course, is the plunge into

dreaming or dream-like states, when the codes of rational thinking are

suspended. The other way is also an escape -- from boredom, stagnation,

intellectual predicaments, and emotional frustration -- but an escape

in the opposite direction; it is signalled by the spontaneous flash of

insight which shows a familiar situation or event in a new light, and

elicits a new response to it. The bisociative act connects previously

unconnected matrices of experience; it makes us 'understand what it is to

be awake, to be living on several planes at once' (to quote T. S. Eliot,

somewhat out of context).

The first way of escape is a regression to earlier, more primitive levels

of ideation, exemplified in the language of the dream; the second an

ascent to a new, more complex level of mental evolution. Though seemingly

opposed, the two processes will turn out to he intimately related.

Man and Machine

When two independent matrices of perception or reasoning interact

with each other the result (as I hope to show) is either a

collision

ending in laughter, or their

fusion

in a new intellectual synthesis,

or their

confrontation

in an aesthetic experience. The bisociative

patterns found in any domain of creative activity are tri-valent:

that is to say, the same pair of matrices can produce comic, tragic,

or intellectually challenging effects.

Let me take as a first example 'man' and 'machine'. A favourite trick of

the coarser type of humour is to exploit the contrast between these two

frames of reference (or between the related pair 'mind' and 'matter'). The

dignified schoolmaster lowering himself into a rickety chair and crashing

to the floor is perceived simultaneously in two incompatible contexts:

authority is debunked by gravity. The savage, wistfully addressing the

carved totem figure -- 'Don't be so proud, I know you from a plum-tree' --

expresses the same idea: hubris of mind, earthy materiality of body. The

variations on this theme are inexhaustible: the person slipping on a

banana skin; the sergeant-major attacked by diarrhoea; Hamlet getting

the hiccoughs; soldiers marching like automata; the pedant behaving

like a mechanical robot; the absent-minded don boiling his watch while

clutching the egg, like a machine obeying the wrong switch. Fate keeps

playing practical jokes to deflate the victim's dignity, intellect, or

conceit by demonstrating his dependence on coarse bodily functions and

physical laws -- by degrading him to an automaton. The same purpose is

served by the reverse technique of making artefacts behave like humans:

Punch and Judy, Jack-in-the-Box, gadgets playing tricks on their masters,

hats in a gust of wind escaping the pursuer as if with calculated malice.

In Henri Bergson's book on the problem of laughter, this dualism of

subtle mind and inert matter ('the mechanical encrusted on the living')

is made to serve as an explanation of

all

forms of the comic; whereas

in the present theory it applies to only one variant of it among many

others. Surprisingly, Bergson failed to see that each of the examples

just mentioned can be convened from a comic into a tragic or purely

intellectual experience, based on the same logical pattern -- i.e. on

the same pair of bisociated matrices -- by a simple change of emotional

climate. The fat man slipping and crashing on the icy pavement will be

either a comic or a tragic figure according to whether the spectator's

attitude is dominated by malice or pity: a callous schoolboy will laugh

at the spectade, a sentimental old lady may be inclined to weep. But

in between these two there is the emotionally balanced attitude of the

physician who happens to pass the scene of the mishap, who may feel both

amusement and compassion, but whose primary concern is to find out the

nature of the injury. Thus the victim of the crash may be seated in any

of the three panels of the triptych. Don Quixote gradually changes from

a comic into a puzzling figure if, instead of relishing his delusions

with arrogant condescension, I become interested in their psychological

causes; and he changes into a tragic figure as detached curiosity turns

into sympathetic identification -- as I recognize in the sad knight my

brother-in-arms in the fight against windmills. The stock characters

in the farce -- the cuckold, the miser, the stutterer, the hunchback,

the foreigner -- appear as comic, intellectually challenging, or tragic

figures according to the different emotional attitudes which they arouse

in spectators of different mental age, culture, or mood.

The 'mechanical encrusted on the living' symbolizes the contrast between

man's spiritual aspirations and his all-too-solid flesh subject to

the laws of physics and chemistry. The practical joker and the clown

specialize in tricks which exploit the mechanical forces of gravity

and inertia to deflate his humanity. But Icarus, too, like the dinner

guest whose chair collapsed, is the victim of a practical joke -- the

gods, instead of breaking the legs of his chair, have melted away his

wings. The second appeals to loftier emotions than the first, but the

logical structure of the two situations and their message is the same:

whatever you fancy yourself to be you are subject to the inverse square

law like any other lump of clay. In one case it is a comic, in the other

a tragic message. The difference is due to the different character of the

emotions involved (malice in the first case, compassionate admiration

in the second); but also to the fact that in the first case the two

frames of reference collide, exploding the tension, while in the second

they remain juxtaposed in a tragic confrontation, and the tension ebbs

away in a slow catharsis. The third alternative is the reconciliation

and synthesis of the two matrices; its effect is neither laughter,

nor tears, but the arousal of curiosity: just

how

is the mechanical

encrusted on the living? How much acceleration can the organism stand,

and how does zero gravity effect it?

According to Bergson, the main sources of the comic are the mechanical

attributes of inertia, rigidity, and repetitiveness impinging on life;

among his favourite examples are the man-automaton, the puppet on strings,

Jack-in-the-Box, etc. However, if rigidity contrasted with organic

suppleness were laughable in itself, Egyptian statues and Byzantine

mosaics would be the best jokes ever invented. If automatic repetativeness

in human behaviour were a necessary and sufficient condition of the

comic, there would be no more amusing spectacle thau an epileptic fit;

and if we wanted a good laugh we would merely have to feel a person's

pulse or listen to his heart-beat, with its monotonous tick-tack. If

'we laugh each time a person gives us the impression of being a thing'

[8] there would be nothing more funny than a corpse.

In fact, every one of Bergson's examples of the comic can be transposed,

along a horizontal line as it were, across the triptych, into the

panels of science and art. His 'homme-automate', man and artefact at

the same time, has its lyric counterpart in Galatea -- the ivory statue

which Pygmalion made, Aphrodite brought to life, and Shaw returned

to the comic domain. It has its tragic counterpart in the legends of

Faust's Homunculus, the Golem of Prague, the monsters of Frankenstein;

its origins reach back to Jehovah manufacturing Adam out of 'adamåh',

the Hebrew word for earth. The reverse transformation -- life into

mechanism -- has equally rich varieties: the pedant whom enslavement to

habit has reduced to an automaton is comic because we despise him; the

compulsion-neurotic is not, because we are puzzled and try to understand

him; the catatonic patient, frozen into a statue, is tragic because we

pity him. And so again back to mythology: Lot's wife turned into a pillar

of salt, Narcissus into a flower, the poor nymph Echo wasting away until

nothing is left but her voice, and her bones changed into rocks.

In the middle panel of the triptych the 'homme-automate' is the

focal, or rather bi-focal, concept of all sciences of life. From their

inception they treated, as the practical joker does, man as both mind

and machine. The Pythagoreans regarded the body as a musical instrument

whose soul-strings must have the right tension, and we still unwittingly

refer to our mortal frame as a kind of stringed guitar when we speak of

'muscle

tone

', or describe John as 'good tempered'. The same bifocal

view is reflected in the four Hippocratic 'humours' -- which were both

liquids of the body and moods of the spirit; and 'spiritus' itself is,

like 'pneuma', ambiguous, meaning also breath. The concept of 'catharsis'

applied, and still does, to the purgation of either the mind or the

bowels. Yet if I were to speak earnestly of halitosis of the soul, or

of laxatives to the mind, or call an outburst of temper a humourrhage,

it would sound ludicrous, because I would make the implicit ambiguities

explicit for the purpose of maliciously contrasting them; I would tear

asunder two frames of reference that our Greek forbears had managed to

integrate, however tentatively, into a unified, psychosomatic view which

our language still reflects.

In modern science it has become accepted usage to speak of the

'mechanisms' of digestion, perception, learning, and cognition, etc.,

and to lay increasing or exclusive stress on the automaton aspect of the

'homme-automate'. The mechanistic trend in physiology reached its symbolic

culmination at the beginning of the century in the slogan 'Man a machine'

-- the programmatic title of a once famous book by Jacques Loeb; it was

taken over by behaviouristic psychology, which has been prominent in

the Anglo-Saxon countries for half a century. Even a genial naturalist

like Konrad Lorenz, whose

King Solomon's Ring

has delighted millions,

felt impelled to proclaim that to regard Newton and Darwin as automata

was the only permissible view for 'the inductive research worker who

does not believe in miracles'. [9] It all depends, of course, on what

one's definition of a miracle is: Galileo, the ideal of all 'inductive

research workers', rejected Kepler's theory that the tides were due to

the moon's attraction as an 'occult fancy'. [10] The intellectual climate

created by these attitudes has been summed up by Cyril Burt, writing

about 'The Concept of Consciousness' (which behaviourists have banned,

as another 'occult fancy', from the vocabulary of science): 'The result,

as a cynical onlooker might be tempted to say, is that psychology, having

first bargained away its soul and then gone out of its mind, seems now,

as it faces an untimely end, to have lost all consciousness.' [11]

I have dwelt at some length on Bergson's favourite example of the comic,

because of its relevance to one of the leitmotifs of this book. The

man-machine duality has been epitomized in a laconic sentence -- 'man

consists of ninety per cent water and ten per cent minerals' -- which one

can regard, according to taste, as comic, intellectually challenging, or

tragic. In the first case one has only to think of a caricature showing a

fat man under the African sun melting away into a puddle; in the second,

of the 'inductive research worker' bent over his test-tube; in the third,

of a handful of dust.

Other examples of Bergson's man-automaton need be mentioned only

briefly. The puppet play in its naïve Punch and Judy version is

comic

;

the sophisticated marionette theatre is a traditional form of

art

;

life-imitating contraptions are used in various branches of

science

and technology: from the dummy figures of dressmakers to the anatomical

models in medical schools; from the artificial limbs of the orthopaedist

to robots imitating the working of the nervous system (such as Grey

Walter's electronic tortoises). In the

metaphorical

sense, the

puppet on strings is a timeless symbol, either comic or tragic, of man

as a plaything of destiny -- whether he is jerked about by the gods

or suspended on his own chromosomes and glands. In the neutral zone

between Comedy and tragedy, philosophers have been tireless in their

efforts to reconcile the two conflicting aspects of the human puppet:

his experience of free will and moral responsibility on the one hand;

the strings of determinism, religious or scientific, on the other.

Other books

Cambridge by Susanna Kaysen

Curio by Evangeline Denmark

Veil - 02 - The Hammer of God by Reginald Cook

World Famous Cults and Fanatics by Colin Wilson

The Fly Trap by Fredrik Sjoberg

This Is What I Want by Craig Lancaster

Divorce Is in the Air: A Novel by Gonzalo Torne

Death Will Have Your Eyes by James Sallis

Overhaul by Steven Rattner

The Final Years of Marilyn Monroe: The Shocking True Story by Keith Badman