The Act of Creation (3 page)

Read The Act of Creation Online

Authors: Arthur Koestler

Furthermore, the same muscle contractions produce different effects

according to whether they expose a set of pearly teeth or a toothless

gap -- producing a smile, a simper, or smirk. Mood also superimposes

its own facial pattern -- hence gay laughter, melancholy smile,

lascivious grin. Lastly, contrived laughter and smiling can

be used as a conventional signal-language to convey pleasure or

embarrassment, friendliness or derision. We are concerned, however,

only with spontaneous laughter as a specific response to the comic;

regarding which we can conclude with Dr. Johnson that 'men have

been wise in very different modes; but they have always laughed in

the same way.'

The Paradox of Laughter

I have taken pains to show that laughter is, in the sense indicated

above, a true reflex, because here a paradox arises which is the starting

point of our inquiry. Motor reflexes, usually exemplified in textbooks

by knee-jerk or pupillary contraction, are relatively simple, direct

responses to equally simple stimuli which, under normal circumstances,

function autonomously, without requiring the intervention of higher

mental processes; by enabling the organism to counter disturbances

of a frequently met type with standardized reactions, they represent

eminently practical arrangements in the service of survival. But what

is the survival value of the involuntary, simultaneous contraction of

fifteen facial muscles associated with certain noises which are often

irrepressible? Laughter is a reflex, but unique in that it serves no

apparent biological purpose; one might call it a luxury reflex. Its only

utilitarian function, as far as one can see, is to provide temporary

relief from utilitarian pressures. On the evolutionary level where

laughter arises, an element of frivolity seems to creep into a humourless

universe governed by the laws of thcrmodynamics and the survival of

the fittest.

The paradox can be put in a different way. It strikes us as a reasonable

arrangement that a sharp light shone into the eye makes the pupil contract,

or that a pin stuck into one's foot causes its instant withdrawal --

because both the 'stimulus' and the 'response' are on the same physiological

level. But that a complicated mental activity like the reading of a page

by Thurber should cause a specific motor response on the reflex level

is a lopsided phenomenon which has puzzled philosophers since antiquity.

There are, of course, other complex intellectual and emotional activities

which also provoke bodily reactions -- frowning, yawning, sweating,

shivering, what have you. But the effects on the nervous system of reading

a Shakespeare sonnet, working on a mathematical problem, or listening

to Mozart are diffuse and indefinable. There is no clear-cut predictable

response to tell me whether a picture in the art gallery strikes another

visitor as 'beautiful'; but there is a predictable facial contraction

which tells me whether a caricature strikes him as 'comic.'

Humour is the only domain of creative activity where a stimulus on a

high level of complexity produces a massive and sharply defined response

on the level of physiological reflexes.

This paradox enables us to use

the response as an indicator for the presence of that elusive quality,

the comic, which we are seeking to define -- as the tell-tale clicking

of the geiger-counter indicates the presence of radioactivity. And

since the comic is related to other, more exalted, forms of creativity,

the backdoor approach promises to yield some positive results. We all

know that there is only one step from the sublime to the ridiculous;

the more surprising that Psychology has not considered the possible

gains which could result from the reversal of that step.

The bibliography of Greig's

Psychology of Laughter and Comedy

, published

in 1923, mentioned three hundred and sixty-three titles of works bearing

partly or entirely on the subject -- from Plato and Aristotle to Kant,

Bergson, and Freud. At the turn of the century T. A. Ribot summed up these

attempts at formulating a theory of the comic: 'Laughter manifests itself

in such varied and heterogeneous conditions . . . that the reduction of

all these causes to a single one remains a very problematical undertaking.

After so much work spent on such a trivial phenomenon, the problem is

still far from being completely explained.' [3] This was written in 1896;

since then only two new theories of importance have been added to the

list: Bergson's

Le Rire

and Freud's

Wit and its Relations to the

Unconscious

. I shall have occasion to refer to them.*

The difficulty lies evidently in the enormous range of laughter-producing

situations -- from physical tickling to mental titillation of the most

varied kinds. I shall try to show that there is unity in this variety;

that the common denominator is of a specific and specifiable pattern

which is of central importance not only in humour but in all domains

of creative activity. The bacillus of laughter is a bug difficult to

isolate; once brought under the microscope, it will turn out to be a

yeast-like, universal ferment, equally useful in making wine or vinegar,

and raising bread.

The Logic of Laughter: A First Approach

Some of the stories that follow, including the first, I owe to my late

friend John von Neumann, who had all the makings of a humorist: he was

a mathematical genius and he came from Budapest.

Two women meet while shopping at the supermarket in the Bronx. One

looks cheerful, the other depressed. The cheerful one inquires:

Chamfort tells a story of a Marquis at the court of Louis XIV who, on

entering his wife's boudoir and finding her in the arms of a Bishop,

walked calmly to the window and went through the motions of blessing

the people in the street.

more than a century apart, follow in fact the same pattern. The Chamfort

anecdote concerns adultery; let us compare it with a tragic treatment of

that subject -- say, in the Moor of Venice. In the tragedy the tension

increases until the climax is reached: Othello strangles Desdemona;

then it ebbs away in a gradual catharsis, as (to quote Aristotle)

'honor and pity accomplish the purgation of the emotions' (see

Fig. 1,a

on next page).

In the Chamfort anecdote, too, the tension mounts as the story progresses,

but it never reaches its expected climax. The ascending curve is brought

to an abrupt end by the Marquis' unexpected reaction, which debunks our

dramatic expectations; it comes like a bolt out of the blue, which, so to

speak, decapitates the logical development of the situation. The narrative

acted as a channel directing the flow of emotion; when the channel is

punctured the emotion gushes out like a liquid through a burst pipe;

the tension is suddenly relieved and exploded in laughter (Fig. 1,b):

I said that this effect was brought about by the Marquis' unexpected

I said that this effect was brought about by the Marquis' unexpected

reaction. However, unexpectedness alone is not enough to produce a comic

effect. The crucial point about the Marquis' behaviour is that it is both

unexpected and perfectly logical -- but of a logic not usually applied

to this type of situation. It is the logic of the division of labour,

the quid pro quo, the give and take; but our expectation was that the

Marquis' actions would be governed by a different logic or code of

behaviour. It is the clash of the two mutually incompatible codes,

or associative contexts, which explodes the tension.

In the Oedipus story we find a similar dash. The cheerful woman's

statement is ruled by the logic of common sense: if Jimmy is a good

boy and loves his mamma there can't be much wrong. But in the context

of Freudian psychiatry the relationship to the mother carries entirely

different associations.

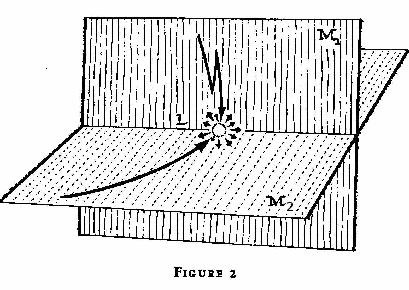

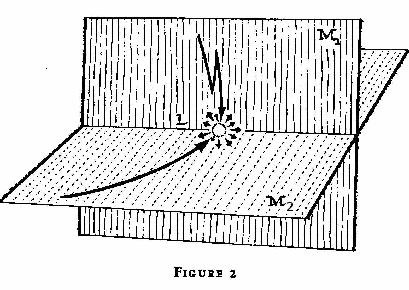

The pattern underlying both stories is

the perceiving of a situation

or idea, L, in two self-consistent but habitually incompatible frames of

reference, M1 and M2

(Fig. 2). The event L, in which the two intersect,

is made to vibrate simultaneously on two different wavelengths, as it

were. While this unusual situation lasts, L is not merely linked to one

associative context, but bisociated with two.

I have coined the term 'bisociation' in order to make a distinction

I have coined the term 'bisociation' in order to make a distinction

between the routine skills of thinking on a single 'plane', as it were,

and the creative act, which, as I shall try to show, always operates on

more than one plane. The former may be called single-minded, the latter

a double-minded, transitory state of unstable equilibrium where the

balance of both emotion and thought is disturbed. The forms which this

creative instability takes in science and art will be discussed later;

first we must test the validity of these generalizations in other fields

of the comic.

At the time when John Wilkes was the hero of the poor and lonely,

an ill-wisher informed him gleefully: 'It seems that some of your

faithful supporters have turned their coats.' 'Impossible,' Wilkes

answered. 'Not one of them has a coat to turn.'

In the happy days of

La Ronde

, a dashing but penniless young

Austrian officer tried to obtain the favours of a fashionable

courtesan To shake off this unwanted suitor, she explained to

him that her heart was, alas, no longer free. He replied politely:

'Mademoiselle, I never aimed as high as that.'

'High' is bisociated with a metaphorical and with a topographical context.

The coat is turned first metaphorically, then literally. In both stories

the literal context evokes visual images which sharpen the clash.

A convict was playing cards with his gaolers. On discovering that

he cheated they kicked him out of gaol.

This venerable chestnut was first quoted by Schopenhaner and has since

been roasted over and again in the literature of the comic. It can be

analysed in a single sentence: two conventional rules ('offenders are

punished by being locked up' and 'cheats are punished by being kicked

out'), each of them self-consistent, collide in a given situation -- as

the ethics of the quid pro quo and of matrimony collide in the Chamfort

story. But let us note that the conflicting rules were merely

implied

in the text; by making them explicit I have destroyed the story's

comic effect.

Shortly after the end of the war a memorable statement appeared in a

fashion article in the magazine

Vogue

:

'sick jokes' of a later decade. The idea of starvation is bisociated

with one tragic, and another, utterly trivial context. The following

quotation from

Time

magazine [5] strikes a related chord:

technically nearer version -- if we have to dwell on blasphemy -- is

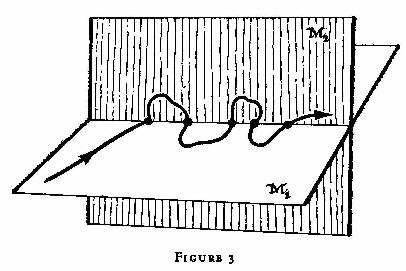

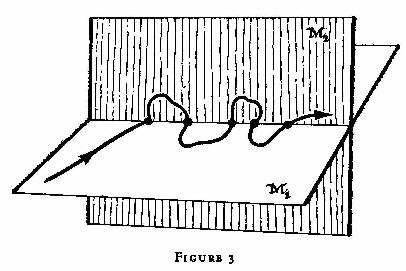

anecdotes with a single point of culmination. The higher forms of

sustained humour, such as the satire or comic poem, do not rely on

a single effect but on a series of minor explosions or a continuous

state of mild amusement. Fig. 3 is meant to indicate what happens when a

humorous narrative oscillates between two frames of reference -- say, the

romantic fantasy world of Don Quixote, and Sancho's cunning horse-sense.

Matrices and Codes

Matrices and Codes

I must now try the reader's patience with a few pages (seven, to be exact)

of psychological speculation in order to introduce a pair of related

concepts which play a central role in this book and are indispensable to

all that follows. I have variously referred to the two planes in Figs. 2

and 3 as 'frames of reference', 'associative contexts', 'types of logic',

'codes of behaviour', and 'universes of discourse'. Henceforth I shall

use the expression 'matrices of thought' (and 'matrices of behaviour') as

a unifying formula. I shall use the word 'matrix' to denote any ability,

habit, or skill, any pattern of ordered behaviour governed by a 'code' of

fixed rules. Let me illustrate this by a few examples on different levels.

The common spider will suspend its web on three, four, and up to twelve

handy points of attachment, depending on the lie of the land, but

the radial threads will always intersect the laterals at equal angles,

according to a fixed code of rules built into the spider's nervous system;

and the centre of the web will always be at its centre of gravity. The

matrix -- the web-building skill -- is flexible: it can be adapted to

environmental conditions; but the rules of the code must be observed

and set a limit to flexibility. The spider's choice of suitable points

of attachment for the web are a matter of strategy, depending on the

environment, but the form of the completed web will always be polygonal,

determined by the code. The exercise of a skill is always under the dual

control (a) of a fixed code of rules (which may be innate or acquired

by learning) and (b) of a flexible strategy, guided by environmental

pointers -- the 'lie of the land'.

As the next example let me take, for the sake of contrast, a matrix

on the lofty level of verbal thought. There is a parlour game where

each contestant must write down on a piece of paper the names of all

towns he can think of starting with a given letter -- say, the letter

'L'. Here the code of the matrix is defined by the rule of the game; and

the members of the matrix are the names of all towns beginning with 'L'

which the participant in question has ever learned, regardless whether

at the moment he remembers them or not. The task before him is to fish

these names out of his memory. There are various strategies for doing

this. One Person will imagine a geographical map, and then scan this

imaginary map for towns with 'L', proceeding in a given direction -- say

west to east. Another person will repeat sub-vocally the syllables

Li,

La, Lo

, as if striking a tuning fork, hoping that his memory circuits

(Lincoln, Lisbon, etc.) will start to 'vibrate' in response. His strategy

determines which member of the matrix will be called on to perform,

and in which order. In the spider's case the 'members' of the matrix

were the various sub-skills which enter into the web-building skill:

the operations of secreting the thread, attaching its ends, judging the

angles. Again, the order and manner in which these enter into action is

determined by strategy, subject to the 'rules of the game' laid down by

the web-building code.

All coherent thinking is equivalent to playing a game according to a set

of rules. It may, of course, happen that in the course of the parlour

game I have arrived via Lagos in Lisbon, and feel suddenly tempted to

dwell on the pleasant memories of an evening spent at the night-club

La Cucaracha in that town. But that would be 'not playing the game',

and I must regretfully proceed to Leeds. Drifting from one matrix to

another characterizes the dream and related states; in the routines of

disciplined thinking only one matrix is active at a time.

In word-association tests the code consists of a single command,

for instance 'name opposites'. The subject is then given a stimulus

word -- say, 'large' -- and out pops the answer: 'small'. If the code

had been 'synonyms', the response would have been 'big' or 'tall',

etc. Association tests are artificial simplifications of the thinking

process; in actual reasoning the codes consist of more or less complex

sets of rules and sub-rules. In mathematical thinking, for instance,

there is a great array of special codes, which govern different types

of operations; some of these are hierarchically ordered, e.g. addition

-- multiplication -- exponential function. Yet the rules of these very

complex games can be represented in 'coded' symbols: x+y, or x.y or x^y or

x÷y, the sight of which will 'trigger off' the appropriate operation --

as reading a line in a piano score will trigger off a whole series of

very complicated finger-movements. Mental skills such as arithmetical

operations, motor skills such as piano-playing or touch-typing, tend

to become with practice more or less automatized, pre-set routines,

which are triggered off by 'coded signals' in the nervous system --

as the trainer's whistle puts a performing animal through its paces.

This is perhaps the place to explain why I have chosen the ambiguous word

'code' for a key-concept in the present theory. The reason is precisely

its nice ambiguity. It signifies on the one hand a set of rules which

must be obeyed -- like the Highway Code or Penal Code; and it indicates

at the same time that it operates in the nervous system through 'coded

signals' -- like the Morse alphabet -- which transmit orders in a kind of

compressed 'secret language'. We know that not only the nervous system

but all controls in the organism operate in this fashion (starting

with the fertilized egg, whose 'genetic code' contains the blue-print

of the future individual. But that blue-print in the cell nucleus does

not show the microscopic image of a little man; it is 'coded' in a kind

of four-letter alphabet, where each letter is represented by a different

type of chemical molecule in a long chain; see Book Two, I).*

according to whether they expose a set of pearly teeth or a toothless

gap -- producing a smile, a simper, or smirk. Mood also superimposes

its own facial pattern -- hence gay laughter, melancholy smile,

lascivious grin. Lastly, contrived laughter and smiling can

be used as a conventional signal-language to convey pleasure or

embarrassment, friendliness or derision. We are concerned, however,

only with spontaneous laughter as a specific response to the comic;

regarding which we can conclude with Dr. Johnson that 'men have

been wise in very different modes; but they have always laughed in

the same way.'

The Paradox of Laughter

I have taken pains to show that laughter is, in the sense indicated

above, a true reflex, because here a paradox arises which is the starting

point of our inquiry. Motor reflexes, usually exemplified in textbooks

by knee-jerk or pupillary contraction, are relatively simple, direct

responses to equally simple stimuli which, under normal circumstances,

function autonomously, without requiring the intervention of higher

mental processes; by enabling the organism to counter disturbances

of a frequently met type with standardized reactions, they represent

eminently practical arrangements in the service of survival. But what

is the survival value of the involuntary, simultaneous contraction of

fifteen facial muscles associated with certain noises which are often

irrepressible? Laughter is a reflex, but unique in that it serves no

apparent biological purpose; one might call it a luxury reflex. Its only

utilitarian function, as far as one can see, is to provide temporary

relief from utilitarian pressures. On the evolutionary level where

laughter arises, an element of frivolity seems to creep into a humourless

universe governed by the laws of thcrmodynamics and the survival of

the fittest.

The paradox can be put in a different way. It strikes us as a reasonable

arrangement that a sharp light shone into the eye makes the pupil contract,

or that a pin stuck into one's foot causes its instant withdrawal --

because both the 'stimulus' and the 'response' are on the same physiological

level. But that a complicated mental activity like the reading of a page

by Thurber should cause a specific motor response on the reflex level

is a lopsided phenomenon which has puzzled philosophers since antiquity.

There are, of course, other complex intellectual and emotional activities

which also provoke bodily reactions -- frowning, yawning, sweating,

shivering, what have you. But the effects on the nervous system of reading

a Shakespeare sonnet, working on a mathematical problem, or listening

to Mozart are diffuse and indefinable. There is no clear-cut predictable

response to tell me whether a picture in the art gallery strikes another

visitor as 'beautiful'; but there is a predictable facial contraction

which tells me whether a caricature strikes him as 'comic.'

Humour is the only domain of creative activity where a stimulus on a

high level of complexity produces a massive and sharply defined response

on the level of physiological reflexes.

This paradox enables us to use

the response as an indicator for the presence of that elusive quality,

the comic, which we are seeking to define -- as the tell-tale clicking

of the geiger-counter indicates the presence of radioactivity. And

since the comic is related to other, more exalted, forms of creativity,

the backdoor approach promises to yield some positive results. We all

know that there is only one step from the sublime to the ridiculous;

the more surprising that Psychology has not considered the possible

gains which could result from the reversal of that step.

The bibliography of Greig's

Psychology of Laughter and Comedy

, published

in 1923, mentioned three hundred and sixty-three titles of works bearing

partly or entirely on the subject -- from Plato and Aristotle to Kant,

Bergson, and Freud. At the turn of the century T. A. Ribot summed up these

attempts at formulating a theory of the comic: 'Laughter manifests itself

in such varied and heterogeneous conditions . . . that the reduction of

all these causes to a single one remains a very problematical undertaking.

After so much work spent on such a trivial phenomenon, the problem is

still far from being completely explained.' [3] This was written in 1896;

since then only two new theories of importance have been added to the

list: Bergson's

Le Rire

and Freud's

Wit and its Relations to the

Unconscious

. I shall have occasion to refer to them.*

The difficulty lies evidently in the enormous range of laughter-producing

situations -- from physical tickling to mental titillation of the most

varied kinds. I shall try to show that there is unity in this variety;

that the common denominator is of a specific and specifiable pattern

which is of central importance not only in humour but in all domains

of creative activity. The bacillus of laughter is a bug difficult to

isolate; once brought under the microscope, it will turn out to be a

yeast-like, universal ferment, equally useful in making wine or vinegar,

and raising bread.

The Logic of Laughter: A First Approach

Some of the stories that follow, including the first, I owe to my late

friend John von Neumann, who had all the makings of a humorist: he was

a mathematical genius and he came from Budapest.

Two women meet while shopping at the supermarket in the Bronx. One

looks cheerful, the other depressed. The cheerful one inquires:

'What's eating you?'The next one is quoted in Freud's essay on the comic.

'Nothing's eating me.'

'Death in the family?'

'No, God forbid!'

'Worried about money?'

'No . . . nothing like that.'

'Trouble with the kids?'

'Well if you must know, it's my little Jimmy.'

'What's wrong with him, then?'

'Nothing is wrong. His teacher said he must see a psychiatrist.'

Pause. 'Well, well, what's wrong with seeing a psychiatrist?'

'Nothing is wrong. The psychiatrist said he's got an Oedipus complex.'

Pause. 'Well, well, Oedipus or Shmoedipus, I wouldn't worry so long as

he's a good boy and loves his mamma.'

Chamfort tells a story of a Marquis at the court of Louis XIV who, on

entering his wife's boudoir and finding her in the arms of a Bishop,

walked calmly to the window and went through the motions of blessing

the people in the street.

'What are you doing?' cried the anguished wife.Both stories, though apparently quite different and in their origin

'Monseigneur is performing my functions,' replied the Marquis,

'so I am performing his.'

more than a century apart, follow in fact the same pattern. The Chamfort

anecdote concerns adultery; let us compare it with a tragic treatment of

that subject -- say, in the Moor of Venice. In the tragedy the tension

increases until the climax is reached: Othello strangles Desdemona;

then it ebbs away in a gradual catharsis, as (to quote Aristotle)

'honor and pity accomplish the purgation of the emotions' (see

Fig. 1,a

on next page).

In the Chamfort anecdote, too, the tension mounts as the story progresses,

but it never reaches its expected climax. The ascending curve is brought

to an abrupt end by the Marquis' unexpected reaction, which debunks our

dramatic expectations; it comes like a bolt out of the blue, which, so to

speak, decapitates the logical development of the situation. The narrative

acted as a channel directing the flow of emotion; when the channel is

punctured the emotion gushes out like a liquid through a burst pipe;

the tension is suddenly relieved and exploded in laughter (Fig. 1,b):

reaction. However, unexpectedness alone is not enough to produce a comic

effect. The crucial point about the Marquis' behaviour is that it is both

unexpected and perfectly logical -- but of a logic not usually applied

to this type of situation. It is the logic of the division of labour,

the quid pro quo, the give and take; but our expectation was that the

Marquis' actions would be governed by a different logic or code of

behaviour. It is the clash of the two mutually incompatible codes,

or associative contexts, which explodes the tension.

In the Oedipus story we find a similar dash. The cheerful woman's

statement is ruled by the logic of common sense: if Jimmy is a good

boy and loves his mamma there can't be much wrong. But in the context

of Freudian psychiatry the relationship to the mother carries entirely

different associations.

The pattern underlying both stories is

the perceiving of a situation

or idea, L, in two self-consistent but habitually incompatible frames of

reference, M1 and M2

(Fig. 2). The event L, in which the two intersect,

is made to vibrate simultaneously on two different wavelengths, as it

were. While this unusual situation lasts, L is not merely linked to one

associative context, but bisociated with two.

between the routine skills of thinking on a single 'plane', as it were,

and the creative act, which, as I shall try to show, always operates on

more than one plane. The former may be called single-minded, the latter

a double-minded, transitory state of unstable equilibrium where the

balance of both emotion and thought is disturbed. The forms which this

creative instability takes in science and art will be discussed later;

first we must test the validity of these generalizations in other fields

of the comic.

At the time when John Wilkes was the hero of the poor and lonely,

an ill-wisher informed him gleefully: 'It seems that some of your

faithful supporters have turned their coats.' 'Impossible,' Wilkes

answered. 'Not one of them has a coat to turn.'

In the happy days of

La Ronde

, a dashing but penniless young

Austrian officer tried to obtain the favours of a fashionable

courtesan To shake off this unwanted suitor, she explained to

him that her heart was, alas, no longer free. He replied politely:

'Mademoiselle, I never aimed as high as that.'

'High' is bisociated with a metaphorical and with a topographical context.

The coat is turned first metaphorically, then literally. In both stories

the literal context evokes visual images which sharpen the clash.

A convict was playing cards with his gaolers. On discovering that

he cheated they kicked him out of gaol.

This venerable chestnut was first quoted by Schopenhaner and has since

been roasted over and again in the literature of the comic. It can be

analysed in a single sentence: two conventional rules ('offenders are

punished by being locked up' and 'cheats are punished by being kicked

out'), each of them self-consistent, collide in a given situation -- as

the ethics of the quid pro quo and of matrimony collide in the Chamfort

story. But let us note that the conflicting rules were merely

implied

in the text; by making them explicit I have destroyed the story's

comic effect.

Shortly after the end of the war a memorable statement appeared in a

fashion article in the magazine

Vogue

:

Belsen and Buchenwald have put a stop to the too-thin woman age,It makes one shudder, yet it is funny in a ghastly way, foreshadowing the

to the cult of undernourishment. [4]

'sick jokes' of a later decade. The idea of starvation is bisociated

with one tragic, and another, utterly trivial context. The following

quotation from

Time

magazine [5] strikes a related chord:

Across the first page of the Christmas issue of the Catholic UniverseHere the frames of reference are the sacred and the vulgarly profane. A

Bulletin, Cleveland's official Catholic diocesan newspaper, ran

this eight-column banner head:

It's a boy in Bethlehem.

Congratulations God -- congratulations Mary -- congratulations

Joseph.

technically nearer version -- if we have to dwell on blasphemy -- is

We wanted a girl.The samples discussed so far all belong to the class of jokes and

anecdotes with a single point of culmination. The higher forms of

sustained humour, such as the satire or comic poem, do not rely on

a single effect but on a series of minor explosions or a continuous

state of mild amusement. Fig. 3 is meant to indicate what happens when a

humorous narrative oscillates between two frames of reference -- say, the

romantic fantasy world of Don Quixote, and Sancho's cunning horse-sense.

I must now try the reader's patience with a few pages (seven, to be exact)

of psychological speculation in order to introduce a pair of related

concepts which play a central role in this book and are indispensable to

all that follows. I have variously referred to the two planes in Figs. 2

and 3 as 'frames of reference', 'associative contexts', 'types of logic',

'codes of behaviour', and 'universes of discourse'. Henceforth I shall

use the expression 'matrices of thought' (and 'matrices of behaviour') as

a unifying formula. I shall use the word 'matrix' to denote any ability,

habit, or skill, any pattern of ordered behaviour governed by a 'code' of

fixed rules. Let me illustrate this by a few examples on different levels.

The common spider will suspend its web on three, four, and up to twelve

handy points of attachment, depending on the lie of the land, but

the radial threads will always intersect the laterals at equal angles,

according to a fixed code of rules built into the spider's nervous system;

and the centre of the web will always be at its centre of gravity. The

matrix -- the web-building skill -- is flexible: it can be adapted to

environmental conditions; but the rules of the code must be observed

and set a limit to flexibility. The spider's choice of suitable points

of attachment for the web are a matter of strategy, depending on the

environment, but the form of the completed web will always be polygonal,

determined by the code. The exercise of a skill is always under the dual

control (a) of a fixed code of rules (which may be innate or acquired

by learning) and (b) of a flexible strategy, guided by environmental

pointers -- the 'lie of the land'.

As the next example let me take, for the sake of contrast, a matrix

on the lofty level of verbal thought. There is a parlour game where

each contestant must write down on a piece of paper the names of all

towns he can think of starting with a given letter -- say, the letter

'L'. Here the code of the matrix is defined by the rule of the game; and

the members of the matrix are the names of all towns beginning with 'L'

which the participant in question has ever learned, regardless whether

at the moment he remembers them or not. The task before him is to fish

these names out of his memory. There are various strategies for doing

this. One Person will imagine a geographical map, and then scan this

imaginary map for towns with 'L', proceeding in a given direction -- say

west to east. Another person will repeat sub-vocally the syllables

Li,

La, Lo

, as if striking a tuning fork, hoping that his memory circuits

(Lincoln, Lisbon, etc.) will start to 'vibrate' in response. His strategy

determines which member of the matrix will be called on to perform,

and in which order. In the spider's case the 'members' of the matrix

were the various sub-skills which enter into the web-building skill:

the operations of secreting the thread, attaching its ends, judging the

angles. Again, the order and manner in which these enter into action is

determined by strategy, subject to the 'rules of the game' laid down by

the web-building code.

All coherent thinking is equivalent to playing a game according to a set

of rules. It may, of course, happen that in the course of the parlour

game I have arrived via Lagos in Lisbon, and feel suddenly tempted to

dwell on the pleasant memories of an evening spent at the night-club

La Cucaracha in that town. But that would be 'not playing the game',

and I must regretfully proceed to Leeds. Drifting from one matrix to

another characterizes the dream and related states; in the routines of

disciplined thinking only one matrix is active at a time.

In word-association tests the code consists of a single command,

for instance 'name opposites'. The subject is then given a stimulus

word -- say, 'large' -- and out pops the answer: 'small'. If the code

had been 'synonyms', the response would have been 'big' or 'tall',

etc. Association tests are artificial simplifications of the thinking

process; in actual reasoning the codes consist of more or less complex

sets of rules and sub-rules. In mathematical thinking, for instance,

there is a great array of special codes, which govern different types

of operations; some of these are hierarchically ordered, e.g. addition

-- multiplication -- exponential function. Yet the rules of these very

complex games can be represented in 'coded' symbols: x+y, or x.y or x^y or

x÷y, the sight of which will 'trigger off' the appropriate operation --

as reading a line in a piano score will trigger off a whole series of

very complicated finger-movements. Mental skills such as arithmetical

operations, motor skills such as piano-playing or touch-typing, tend

to become with practice more or less automatized, pre-set routines,

which are triggered off by 'coded signals' in the nervous system --

as the trainer's whistle puts a performing animal through its paces.

This is perhaps the place to explain why I have chosen the ambiguous word

'code' for a key-concept in the present theory. The reason is precisely

its nice ambiguity. It signifies on the one hand a set of rules which

must be obeyed -- like the Highway Code or Penal Code; and it indicates

at the same time that it operates in the nervous system through 'coded

signals' -- like the Morse alphabet -- which transmit orders in a kind of

compressed 'secret language'. We know that not only the nervous system

but all controls in the organism operate in this fashion (starting

with the fertilized egg, whose 'genetic code' contains the blue-print

of the future individual. But that blue-print in the cell nucleus does

not show the microscopic image of a little man; it is 'coded' in a kind

of four-letter alphabet, where each letter is represented by a different

type of chemical molecule in a long chain; see Book Two, I).*

Other books

The Duke Diaries by Sophia Nash

A Firm Merger by Ganon, Stephanie

Her Forgotten Betrayal by Anna DeStefano

The Holocaust by Martin Gilbert

The Girl Who Tweeted Wolf by Nick Bryan

Last Blood by Kristen Painter

Watcher: A raven paranormal romance (Crookshollow ravens Book 1) by Steffanie Holmes

Chasing Schrödinger’s Cat - A Steampunk Novel by Tom Hourie

Octobers Baby by Glen Cook

Summer Garden Murder by Ann Ripley