The Act of Creation (10 page)

Read The Act of Creation Online

Authors: Arthur Koestler

None of this was said; all of it was implied. But the listener has to

work out by himself what is implied in the laconic hint; he has to make

an imaginative effort to solve the riddle. If the answer were explicitly

given, on the lines indicated in the previous paragraph, the listener

would be both spared the effort and deprived of its reward; there would

be no anecdote to tell.

To a sophisticated audience any joke sounds stale if it is entirely

explicit. If this is the case the listener's thoughts will move faster

than the narrator's tale or the unfolding of the plot; instead of tension

it will generate boredom. 'Economy' in this sense means the use of hints

in lieu of statements; instead of moving steadily on, the narrative

jumps ahead, leaving logical gaps which the listener has to bridge by

his own effort: he is forced to co-operate.

The operation of bridging a logical gap by inserting the missing links is

called

interpolation

. The series A, C, E, . . . K, M, O shows

a gap which is filled by interpolating G and I. On the other hand,

I can extend or

extrapolate

the series by adding to it R, T,

V, etc. In the more sophisticated forms of humour the listener must

always perform either or both of these operations before he can 'see

the joke'. Take this venerable example, quoted by Freud:

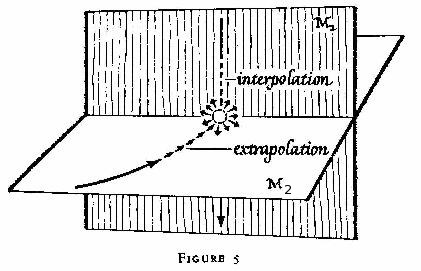

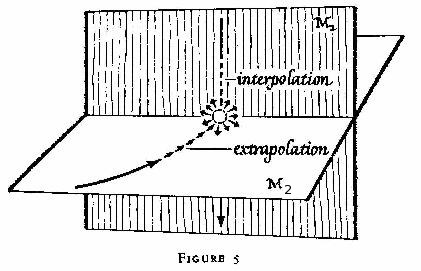

behaviour are brought into collision: feudal lords were supposed to have

bastards; feudal ladies were not supposed to have bastards; and there is

a particularly neat, quasi-geometrical link provided by the reversible

symmetry of the situation. The mild amusement which the story offers

is partly derived from the malicious pleasure we take in the Prince's

discomfiture; but mainly from the fact that it is put in the form of a

riddle, of two oblique hints which the listener must complete under his

own steam, as it were. The dotted lines in the figure below indicate the

process (the arrow in M1 may be taken to represent the Prince's question,

the other arrow, the reply).

Incidentally, Wilde has coined a terser variation on the same theme:

Incidentally, Wilde has coined a terser variation on the same theme:

implication -- the hint, the oblique allusion -- in varying degrees:

the good little boy who loves his mama; the man who never aimed as

high as that; the kind sadist, etc. Apart from inter- and extrapolation

(there is no need for our purposes to make a distinction between them) a

third type of operation is often needed to enable one to 'see the joke':

transformation

, or reinterpretation, of the given data into

some analogous terms. These operations comprise the transformation of

metaphorical into literal statements, of verbal hints into visual terms,

and the interpretation of visual riddles of the "New Yorker" cartoon

type. A good example ('good', I am afraid, only from a theoretical point

of view) is provided by another story, quoted from Freud:

Economy

, in humour as in art, does not mean mechanical brevity but

implicitness.

Implicit

is derived from the Latin word for 'folded

in'. To make a joke like Picasso's 'unfold', the listener must fill in

the gaps, complete the hints, trace the hidden analogies. Every good

joke contains an element of the riddle -- it may be childishly simple,

or subtle and challenging -- which the listener must solve. By doing

so, he is lifted out of his passive role and compelled to co-operate,

to repeat to some extent the process of inventing the joke, to re-create

it in his imagination. The type of entertainment dished out by the mass

media makes one apt to forget that true recreation is re-creation.

Emphasis

and

implication

are complementary techniques. The

first bullies the audience into acceptance; the second entices it into

mental collaboration; the first forces the offer down the consumer's

throat; the second tantalizes, to whet his appetite.

In fact, both techniques have their roots in the basic mechanisms

of communicating thoughts by word or sign. Language itself is never

completely explicit. Words have suggestive, evocative powers; but at the

same time they are merely stepping stones for thought. Economy means

spacing them at intervals just wide enough to require a significant

effort from the receiver of the message; the artist rules his subjects

by turning them into accomplices.

NOTE

To

p. 70

. Cf. the analysis of an Osbert Lancaster

cartoon in

Insight and Outlook

, p. 80 f.

IV

FROM HUMOUR TO DISCOVERY

Explosion and Catharsis

Primitive jokes arouse crude, aggressive, or sexual emotions by means

of a minimum of ingenuity. But even the coarse laughter in which these

emotions are exploded often contains an additional element of admiration

for the cleverness of the joke -- and also of satisfaction with one's

own cleverness in seeing the joke. Let us call this additional element

of admiration plus self-congratulation the intellectual gratification

offered by the joke.

Satisfaction presupposes the existence of a need or appetite. Intellectual

curiosity, the desire to understand, is derived from an urge as basic

as hunger or sex: the exploratory drive (see below,

XI

, and

Book Two, VIII

). It is

the driving power which makes the rat learn to find its way through

the experimental maze without any obvious incentive being offered in

the form of reward or punishment; and also the prime-mover behind human

exploration and research. Its 'detached' and' disinterested' character --

the scientists' self-transcending absorption in the riddles of nature --

is, of course, often combined with ambition, competition, vanity: But

these self-assertive tendencies must be restrained and highly sublimated

to find fulfilment in the mostly unspectacular rewards of his slow and

patient labours. There are, after all, more direct methods of asserting

one's ego than the analysis of ribonucleic acids.

When I called discovery the emotionally 'neutral' art I did not mean

by neutrality the absence of emotion -- which would be equivalent to

apathy - -but that nicely balanced and sublimated blend of motivations,

where self-assertiveness is harnessed to the task; and where on the other

hand heady speculations about the Mysteries of Nature must be submitted

to the rigours of objective verification.

We shall see that there are two sides to the manifestation of

emotions at the moment of discovery, which reflect this polarity of

motivations. One is the triumphant explosion of tension which has

suddenly become redundant since the problem is solved -- so you jump

out of your bath and run through the streets laughing and shouting

Eureka! In the second place there is the slowly fading after-glow,

the gradual catharsis of the self-transcending emotions -- a quiet,

contemplative delight in the truth which the discovery revealed, closely

related to the artist's experience of beauty. The Eureka cry is the

explosion of energies which must find an outlet since the purpose for

which they have been mobilized no longer exists; the carthartic reaction

is an inward unfolding of a kind of 'oceanic feeling', and its slow

ebbing away. The first is due to the fact that 'I' made a discovery;

the second to the fact that a discovery has been made, a fraction of

the infinite revealed. The first tends to produce a state of physical

agitation related to laughter; the second tends towards quietude, the

'earthing' of emotion, sometimes a peaceful overflow of tears. The

reasons for this contrast will be discussed later; for the time being,

let us remember that, physiologically speaking, the self-assertive

tendencies operate through the massive sympathico-adrenal system which

galvanizes the body into activity -- whereas the self-transcending

emotions have no comparable trigger-mechanism at their disposal, and

their bodily manifestations are in every respect the opposite of the

former: pulse and breathing are slowed down, the muscles relax, the

whole organism tends towards tranquillity and catharsis. Accordingly,

this class of emotions is devoid of the inertial momentum which makes

the rage-fear type of reactions so often fall out of step with reasoning;

the participatory emotions do not become dissociated from thought. Rage

is immune to understanding; love of the self-transcending variety is

based on understanding, and cannot be separated from it.

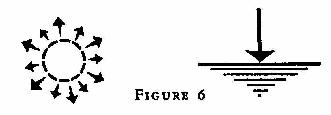

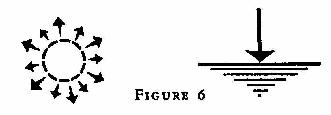

Thus the impact of a sudden, bisociative surprise which makes reasoning

perform a somersault will have a twofold effect: part of the tension

will become detached from it and exploded while the remaining part will

slowly ebb away. The symbols

on the triptych are meant to refer to these two modes of the discharge

on the triptych are meant to refer to these two modes of the discharge

of tension: the

explosion

of the aggressive-defensive and the

gradual catharsis, or 'earthing', of the participatory emotions.

'Seeing the Joke' and 'Solving the Problem'

The dual manifestation of emotions at the moment of discovery is reflected

on a minor and trivial scale in our reactions to a clever joke. The

pleasant after-glow of admiration and intellectual satisfaction, gradually

fading, reflects the cathartic reaction; while the self-congratulatory

impulse -- a faint echo of the Eureka cry -- supplies added voltage

to the original charge detonated in laughter: that 'sudden glory'

(as Hobbes has it) 'arising out of our own eminency'.

Let our imagination travel once more across the

triptych

of creative activities

, from left to right, as it were. We can do

this as we have seen, by taking a short-cut from one wing to another,

from the comic to the tragic or sublime; or alternatively by following

the gradual transitions which lead from the left to the centre panel.

On the extreme left of the continuum -- the infra-red end of the emotive

spectrum -- we found the practical joke, the smutty story, the lavatory

humour of children, each with a heavy aggressive or sexual or scatalogical

load (which may be partly unconscious); and with a logical structure

so obvious that it required only a minimum of intellectual effort to

'see the joke'. Put into a formula, we could say that the ratio A: I --

where A stands for crude emotion, and I for intellectual stimulation --

is heavily loaded in favour of the former.

As we move across the panel towards the right, this ratio changes, and

is ultimately reversed. In the higher forms of comedy, satire, and irony

the message is couched in implicit and oblique terms; the joke gradually

assumes the character of an epigram or riddle, the witticism becomes a

challenge to our wits:

malicious ingenuity; gross sexuality into subtle eroticism. Incidentally,

if I had not mentioned that the last quotation was by Heine, whose name

combined with 'virgin' arouses ominous expectations, but had pretended

instead that it was from a novel by D. H. Lawrence, it would probably

have impressed the reader as profoundly poetic instead of malicious --

a short-cut from wing to wing, by reversal of the charge from minus

to plus. Again, imagine for a moment that the quotation occurred in an

essay by a Jungian psychologist -- and it will turn into an emotionally

neutral illustration of 'the intrusion of archetypes into perception'.

work out by himself what is implied in the laconic hint; he has to make

an imaginative effort to solve the riddle. If the answer were explicitly

given, on the lines indicated in the previous paragraph, the listener

would be both spared the effort and deprived of its reward; there would

be no anecdote to tell.

To a sophisticated audience any joke sounds stale if it is entirely

explicit. If this is the case the listener's thoughts will move faster

than the narrator's tale or the unfolding of the plot; instead of tension

it will generate boredom. 'Economy' in this sense means the use of hints

in lieu of statements; instead of moving steadily on, the narrative

jumps ahead, leaving logical gaps which the listener has to bridge by

his own effort: he is forced to co-operate.

The operation of bridging a logical gap by inserting the missing links is

called

interpolation

. The series A, C, E, . . . K, M, O shows

a gap which is filled by interpolating G and I. On the other hand,

I can extend or

extrapolate

the series by adding to it R, T,

V, etc. In the more sophisticated forms of humour the listener must

always perform either or both of these operations before he can 'see

the joke'. Take this venerable example, quoted by Freud:

The Prince, travelling through his domains, noticed a man in theThe logical pattern of the story is quite primitive. Two implied codes of

cheering crowd who bore a striking resemblance to himself. He beckoned

him over and asked: 'Was your mother ever employed in my palace?'

'No, Sire,' the man replied. 'But my father was.'

behaviour are brought into collision: feudal lords were supposed to have

bastards; feudal ladies were not supposed to have bastards; and there is

a particularly neat, quasi-geometrical link provided by the reversible

symmetry of the situation. The mild amusement which the story offers

is partly derived from the malicious pleasure we take in the Prince's

discomfiture; but mainly from the fact that it is put in the form of a

riddle, of two oblique hints which the listener must complete under his

own steam, as it were. The dotted lines in the figure below indicate the

process (the arrow in M1 may be taken to represent the Prince's question,

the other arrow, the reply).

Lord Illingworth: 'You should study the Peerage, Gerald. . . .Nearly all the stories that I have quoted show the technique of

It is the best thing in fiction the English have ever done.'

implication -- the hint, the oblique allusion -- in varying degrees:

the good little boy who loves his mama; the man who never aimed as

high as that; the kind sadist, etc. Apart from inter- and extrapolation

(there is no need for our purposes to make a distinction between them) a

third type of operation is often needed to enable one to 'see the joke':

transformation

, or reinterpretation, of the given data into

some analogous terms. These operations comprise the transformation of

metaphorical into literal statements, of verbal hints into visual terms,

and the interpretation of visual riddles of the "New Yorker" cartoon

type. A good example ('good', I am afraid, only from a theoretical point

of view) is provided by another story, quoted from Freud:

Two shady business men have succeeded in making a fortune and wereA nice combination of transformation with interpolation.

trying to elbow their way into Society. They had their portraits

painted by a fashionable artist; framed in gold, these were shown at

a reception in the grand style. Among the guests was a well-known

art critic. The beaming hosts led him to the wall on which the two

portraits were hanging side by side. The critic looked at them for

a long time, then shook his head as if he were missing something. At

length he pointed to the bare space between the pictures and asked:

'And where is the Saviour?'

Economy

, in humour as in art, does not mean mechanical brevity but

implicitness.

Implicit

is derived from the Latin word for 'folded

in'. To make a joke like Picasso's 'unfold', the listener must fill in

the gaps, complete the hints, trace the hidden analogies. Every good

joke contains an element of the riddle -- it may be childishly simple,

or subtle and challenging -- which the listener must solve. By doing

so, he is lifted out of his passive role and compelled to co-operate,

to repeat to some extent the process of inventing the joke, to re-create

it in his imagination. The type of entertainment dished out by the mass

media makes one apt to forget that true recreation is re-creation.

Emphasis

and

implication

are complementary techniques. The

first bullies the audience into acceptance; the second entices it into

mental collaboration; the first forces the offer down the consumer's

throat; the second tantalizes, to whet his appetite.

In fact, both techniques have their roots in the basic mechanisms

of communicating thoughts by word or sign. Language itself is never

completely explicit. Words have suggestive, evocative powers; but at the

same time they are merely stepping stones for thought. Economy means

spacing them at intervals just wide enough to require a significant

effort from the receiver of the message; the artist rules his subjects

by turning them into accomplices.

NOTE

To

p. 70

. Cf. the analysis of an Osbert Lancaster

cartoon in

Insight and Outlook

, p. 80 f.

IV

FROM HUMOUR TO DISCOVERY

Explosion and Catharsis

Primitive jokes arouse crude, aggressive, or sexual emotions by means

of a minimum of ingenuity. But even the coarse laughter in which these

emotions are exploded often contains an additional element of admiration

for the cleverness of the joke -- and also of satisfaction with one's

own cleverness in seeing the joke. Let us call this additional element

of admiration plus self-congratulation the intellectual gratification

offered by the joke.

Satisfaction presupposes the existence of a need or appetite. Intellectual

curiosity, the desire to understand, is derived from an urge as basic

as hunger or sex: the exploratory drive (see below,

XI

, and

Book Two, VIII

). It is

the driving power which makes the rat learn to find its way through

the experimental maze without any obvious incentive being offered in

the form of reward or punishment; and also the prime-mover behind human

exploration and research. Its 'detached' and' disinterested' character --

the scientists' self-transcending absorption in the riddles of nature --

is, of course, often combined with ambition, competition, vanity: But

these self-assertive tendencies must be restrained and highly sublimated

to find fulfilment in the mostly unspectacular rewards of his slow and

patient labours. There are, after all, more direct methods of asserting

one's ego than the analysis of ribonucleic acids.

When I called discovery the emotionally 'neutral' art I did not mean

by neutrality the absence of emotion -- which would be equivalent to

apathy - -but that nicely balanced and sublimated blend of motivations,

where self-assertiveness is harnessed to the task; and where on the other

hand heady speculations about the Mysteries of Nature must be submitted

to the rigours of objective verification.

We shall see that there are two sides to the manifestation of

emotions at the moment of discovery, which reflect this polarity of

motivations. One is the triumphant explosion of tension which has

suddenly become redundant since the problem is solved -- so you jump

out of your bath and run through the streets laughing and shouting

Eureka! In the second place there is the slowly fading after-glow,

the gradual catharsis of the self-transcending emotions -- a quiet,

contemplative delight in the truth which the discovery revealed, closely

related to the artist's experience of beauty. The Eureka cry is the

explosion of energies which must find an outlet since the purpose for

which they have been mobilized no longer exists; the carthartic reaction

is an inward unfolding of a kind of 'oceanic feeling', and its slow

ebbing away. The first is due to the fact that 'I' made a discovery;

the second to the fact that a discovery has been made, a fraction of

the infinite revealed. The first tends to produce a state of physical

agitation related to laughter; the second tends towards quietude, the

'earthing' of emotion, sometimes a peaceful overflow of tears. The

reasons for this contrast will be discussed later; for the time being,

let us remember that, physiologically speaking, the self-assertive

tendencies operate through the massive sympathico-adrenal system which

galvanizes the body into activity -- whereas the self-transcending

emotions have no comparable trigger-mechanism at their disposal, and

their bodily manifestations are in every respect the opposite of the

former: pulse and breathing are slowed down, the muscles relax, the

whole organism tends towards tranquillity and catharsis. Accordingly,

this class of emotions is devoid of the inertial momentum which makes

the rage-fear type of reactions so often fall out of step with reasoning;

the participatory emotions do not become dissociated from thought. Rage

is immune to understanding; love of the self-transcending variety is

based on understanding, and cannot be separated from it.

Thus the impact of a sudden, bisociative surprise which makes reasoning

perform a somersault will have a twofold effect: part of the tension

will become detached from it and exploded while the remaining part will

slowly ebb away. The symbols

of tension: the

explosion

of the aggressive-defensive and the

gradual catharsis, or 'earthing', of the participatory emotions.

'Seeing the Joke' and 'Solving the Problem'

The dual manifestation of emotions at the moment of discovery is reflected

on a minor and trivial scale in our reactions to a clever joke. The

pleasant after-glow of admiration and intellectual satisfaction, gradually

fading, reflects the cathartic reaction; while the self-congratulatory

impulse -- a faint echo of the Eureka cry -- supplies added voltage

to the original charge detonated in laughter: that 'sudden glory'

(as Hobbes has it) 'arising out of our own eminency'.

Let our imagination travel once more across the

triptych

of creative activities

, from left to right, as it were. We can do

this as we have seen, by taking a short-cut from one wing to another,

from the comic to the tragic or sublime; or alternatively by following

the gradual transitions which lead from the left to the centre panel.

On the extreme left of the continuum -- the infra-red end of the emotive

spectrum -- we found the practical joke, the smutty story, the lavatory

humour of children, each with a heavy aggressive or sexual or scatalogical

load (which may be partly unconscious); and with a logical structure

so obvious that it required only a minimum of intellectual effort to

'see the joke'. Put into a formula, we could say that the ratio A: I --

where A stands for crude emotion, and I for intellectual stimulation --

is heavily loaded in favour of the former.

As we move across the panel towards the right, this ratio changes, and

is ultimately reversed. In the higher forms of comedy, satire, and irony

the message is couched in implicit and oblique terms; the joke gradually

assumes the character of an epigram or riddle, the witticism becomes a

challenge to our wits:

Psychoanalysis is the disease for which it pretends to be the cure.Or, Heine's description of a young virgin:

Philosophy is the systematic abuse of a terminology specially invented

for that purpose.

Statistics are like a bikini. What they reveal is suggestive. What they

conceal is vital.

Her face is like a palimpsest -- beneath the Gothic lettering of theThe crude aggression of the practical joke has been sublimated into

monk's sacred text lurks the pagan poet's half-effaced erotic verse.

malicious ingenuity; gross sexuality into subtle eroticism. Incidentally,

if I had not mentioned that the last quotation was by Heine, whose name

combined with 'virgin' arouses ominous expectations, but had pretended

instead that it was from a novel by D. H. Lawrence, it would probably

have impressed the reader as profoundly poetic instead of malicious --

a short-cut from wing to wing, by reversal of the charge from minus

to plus. Again, imagine for a moment that the quotation occurred in an

essay by a Jungian psychologist -- and it will turn into an emotionally

neutral illustration of 'the intrusion of archetypes into perception'.

Other books

Cold Light by Frank Moorhouse

A Teeny Bit of Trouble by Michael Lee West

Flame of Sevenwaters by Juliet Marillier

Alexandra Waring by Laura Van Wormer

No Greater Loyalty by S. K. Hardy

Casca 7: The Damned by Barry Sadler

Highlander Unraveled (Highland Bound Book 6) by Eliza Knight

The Campus Trilogy by Anonymous

The Innocent: The New Ryan Lock Novel by Sean Black

Only for You by Beth Kery