Stars of David (33 page)

But when she went to Israel for the first time, she was overcome. “I remember being on the airplane with the Israelisâwhen they sighted land, they started singing âHatikva.' Well . . .” Her eyes fill. “We stepped off the plane and you saw Jewish soldiers and Jewish policemen and Jewish everything: It was overwhelming. But look what they did, how they fucked it up.

“I always talk about this,” she continues, “but George Steinerâthe philosopherâwrote a piece in 1948 about his fears about the creation of the state of Israel. And he said the reason that Jews all over the world have made contributions in all kinds of disciplinesâway in excess of their populationâis because they were outsiders. They couldn't own land, couldn't go into business, couldn't be soldiers. They didn't have a flag or an anthem or a boundary. Being on the outside, they were observers, commentatorsâ through art or whatever else. And he warned the Jews of Israel that this could be the beginning of the end. And oh boy, I think about that piece more often than I care to. Very prescient and true.”

For the Bergmans, longtime progressives, politics and religion seem inextricable. “If you take the Jews out of it, the liberal movement is a very lonely place,” Marilyn says. “That's true everywhere. Which is one of the reasons I think we're a politically endangered species . . . I don't understand how a black woman like Condoleezza Riceâhow can somebody who comes from an oppressed minority, whether they be Jewish or blackâcan identify with the very forces that suppress their people? It's a contradiction in terms. I think if this administration should be elected again [we met before the 2004 election], I don't think we will recognize this country. I don't think anybody of any political persuasion that

I

can identify with will be safe. And I don't think that's paranoid.

“The larger question you're getting at is deeper, though: What does it mean to feel Jewish? I don't know. It's such a rich soup.”

“I'm sure if you would ask people,” Alan says, “âWould you rather be something other than Jewish?' you would get the answer, âNo.'”

“Oh, it's inconceivable,” says Marilyn. “It's essential.”

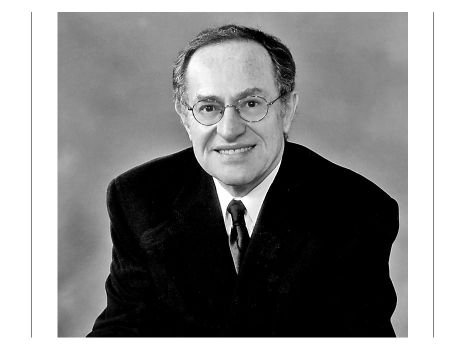

Alan Dershowitz

TREKKING ACROSS HARVARD SQUARE in the driving rain to visit law professor Alan Dershowitz, I can't help but feel I'm braving the elements to get to America's Ãber Jew.

Dershowitz's celebrity derives not just from having been appointed to Harvard Law School's faculty at a mere twenty-five-year-old in 1963âhe's now sixty-sevenânor from defending such notorious figures as O. J. Simpson, Michael Milken, Mike Tyson, Leona Helmsley, and Claus Von Bulow. His renown was also cultivated from his big mouthâthe nation's reliable megaphone for Jewish interests, showing no hesitation to cry anti-Semitism when he sees it (even when others don't), and definingâeven embracingâthe prototype of the brilliant, pushy Jew.

When I enter his disheveled office, he announces that he can give me only a half hour because he has to leave for the annual reunion of his oldest childhood friendsâall Jewishâfrom Brooklyn. “This year we're going to Foxwoods,” he says with a smile, referring to the hotel and casino in Connecticut. (Other years they've gathered at his summer home on Martha's Vineyard.) Dershowitz is rushed, but he doesn't seem as manic as usual. His hair is tamer than I remember it from his countless media appearances or from Ron Silver's portrayal of him in

Reversal of Fortune

in 1990. He looks downright suburban-conventional, wearing a blue V-neck sweater and tilting back in his black office chair.

“I'm a kind of anti-theological Jew,” he says, rocking. “I don't buy into the theology. On the other hand, I have enormous respect for Judaism as a civilization. I look to Jewish sources. For example, I have a very large collection of responsa. What is responsa? It's the Jewish common law. I don't care what the rabbis say about whether you can mix milk with meat, but I'm fascinated by the way they answer deep moral questions. So, when I have a complex philosophical question, I'm likely to look to Jefferson

and

Maimonides without any feeling of inconsistency; they're both brilliant men. In fact, I even look to Jesus, who was a great Jewish rabbiânot Christ, but the rabbinical Jesus. I teach a course in scriptural sources of justice. Students ask me all the time how come I'm always quoting the Torah and the Talmud in my classes, and I throw back at them, âHow come you're always quoting Blackstone?' [Sir William Blackstone was the eighteenth-century British jurist whose writings greatly influenced American law.] We look to what sources we find meaningful or relevant.”

Dershowitz had an Orthodox upbringing in Brooklyn and a tight group of buddies who were determined to succeed not by joining the crowd but by beating them. “We were out to prove a point,” he wrote in his 1991 book,

Chutzpah

. “Not to become assimilated.”

They created the Knight House in high schoolâa sports team made up entirely of Orthodox schoolmates. “Let me tell you, the greatest thrill in my life was when Knight House won the athletic championships at Brooklyn College.” Dershowitz beams. “When us nerdy Orthodox Jews beat all those kids . . .” He shakes his head, still marveling today. “Of course, I considered the people we were beating to be the WASPs of the world, when in fact they were only Conservative and Reform Jews, a couple of Italians, and a few Irish kids. But when we became the athletic champs, it was like Israel winning the Six Day War. We were defying all the stereotypes.”

He never felt like he was missing out on the popular clique or the prettiest girls. “I think our attitude was more, âWhy don't we run one of ourâ quoteâ“girls” as homecoming queen?' We thought that the young women we were going out with were as beautiful as anyone else. We never said, âYou look too Jewish.' And it's interesting that all the eight couplesâall sixteen of usâhave very different views of the world, different views on Democrats, Republicans, different levels of wealth, but we all are deeply Jewish in different ways.”

Dershowitz's Jewishness is no longer by the book. He abandoned morning davening, he says, because of his children. “All the ritual was for

other

people. In the beginning of my life, the âother people' in my life were my parents, so I did it for them. Then, when the more important people in my life became my children, I stopped doing the ritual for them. I couldn't justify it, I couldn't give them my parents' answer: âBecause that's the way we did it.' I wanted to bring my children up with a rational view of Judaism, a view which I could explain: âJudaism is community.' And so I held on to the traditions that create community: The Shabbat dinner is a very important part of our life, for instance. Also the Passover seder, synagogue membership. But the tallis and tefillin were not an important part of my life.”

He didn't want his kids to be trained in ritual he no longer practiced himself. “I didn't want to tell them, âI'm doing this, even though I don't believe it.' I wanted to explain how everything I was doing was integrated into my life. If I have one core in my life, it's that I must be an integrated being. I tell my students all the time, âI can't stand the idea of being a Friday, Saturday, or Sunday religious person, and then Monday through Friday at university you're a secularist, an atheist, an agnostic. You must integrate your worldviews.' My life has a theme . . . And I wanted to give that to my childrenâan integrated view.

“And of course it produced, as you might imagine, three very different children. One of my sons (Jamin), is virulently anti-religious, one (Elon) is moderately traditional and loves the ritual, and I have a daughter (Ella) who is too young to make judgments about it but who goes to a Jewish schoolâReform.” (Ella, by his second marriage to Carolyn Cohen, is thirteen at the time of our conversation, recently a bat mitzvah.)

Jamin is married to a non-Jewish woman. “The departure wasn't so important to me,” he insists. “What I wanted, if I could have my preference about my children, was for my son's Jewishness to be so important to him that it would be natural for him to want to marry someone who he shared that Jewishness with. That's the way it was with me: I didn't marry my wife because I went out and picked somebody who was Jewish. I went out to pick a wife with whom I have a lot in common. I happened to meet her at a Jewish event and we have a tremendous amount in common because we had common approaches toward our Judaism. The fact that my son married someone who wasn't Jewish was a natural result of him being a rebel and rebelling particularly against the religion.”

But Dershowitz points out that Jamin is still a Jew, whether he chooses to embrace Judaism or not. “His name is Dershowitz, his kids go to the Horace Mann School [which has traditionally had a large proportion of Jewish students], they live on the Upper West Side [heavily Jewish], and everybody else assumes that they're Jewish. And the kids, with the name Dershowitz, are identified as Jews whether halachically [according to Jewish law] they are or they aren't.”

I try to get at whether his son's rejection of Judaism was painful at all. “I wouldn't use that description,” Dershowitz replies. “I would say that it made me understand the consequences of giving children freedom. My mother is almost ninety years old. She comes with me every time I speak in New York and everybody comes over to her and says, âYou must be

schepping

[taking in] such

naches

[pride].' And she says, âNo, no, no; it's all my fault that he's not Orthodox. I let him go to Brooklyn College.' And of course she's one hundred percent right. I grew up in a very strictly Orthodox background, and if she had kept me there, I would have not known my alternatives. I wanted to give my kids the maximum alternatives and let them choose. I'm not in control of their lives.”

But in his book

The Vanishing American Jew

, he writes in stronger terms about the issues raised by Jamin's marriage:

I do not want my grandchildren and great-grandchildren to break our link with Judaism. I do not want them to become the first non-Jews in our family history . . . I want them to stay Jewish, not because Jewish is better but because Jewish is what we have been for thousands of years . . . I would not be as troubled as I obviously am about the prospect of having grandchildren who are not Jewish or who are of mixed religious heritage. But the empirical evidence suggests that the children and grandchildren of mixed marriages in which neither party converts tend to abandon their Jewish heritage.

Is he concerned with continuity in his own familyâkeeping the tradition alive? “I don't believe in the life-support theory of Judaism,” he says, rocking again. “I don't want to keep it going just to deny Hitler a posthumous victory, as a rabbi in Canada said. If Judaism has enough that's positive to offer coming generations, then it should thrive. The theory I raise in my book

The Vanishing American Jew

is: Is it possible that Judaism can thrive only in a context of persecution? Is it possible that Judaism has never developed the tools for living in a free and open society of choice? We may never know that, because just as we thought anti-Semitism was over in the late nineties, it's coming back. And we have a lot of Jews now returning to Judaism because of French anti-Semitism. But that's not a good reason for being a Jew.”

He tells a story to illustrate how Jews end up feeling more solidarity when threatened than when they're simply encouraged to embrace their heritage. “Columbia University asked me a few years ago to come and speak because the Jews were not identifying as Jews at Columbiaâof all places. I said, âI can't do it in the next month, but call me back in two months.' They called me back and said, âWe don't need you anymore; we got somebody better who came and really organized the Jewish community together: Louis Farrakhan.' When he came to speak, everybody remembered they were Jewish. That tells a very important story: Farrakhan, who preaches negativesâanti-Semitismâdoes a better job in bringing the Jews together than I, who preach a very positive Judaismânot a defensive or persecution-oriented Judaism.”

I comment that “positive Judaism” seems to be a harder sell; many of the Jews I'm talking to feel pride in being Jewish but don't prioritize Judaism. Dershowitz nods. “In

The Vanishing American Jew

, I propose âThe Candle Theory' of Judaism: The closer you get to the flame of Judaism, the less likely you are to be a productive, successful, creative person. The great successes in Judaism are people who moved away from the flame. But the problem with that is that the further you move away from the flame, the less likely you are to have Jewish children and grandchildren. It's a great paradox. There's no answer. You need to be the right distance away. If you look at almost all the great people that Judaism has produced over time, you find that many of them do not have Jewish grandchildren. Particularly in this century.”

And he doesn't perceive that as a loss? “I don't make a moral judgment about it. If it's a loss, it says something about the imperfections of Judaism. It says something about Judaism being a culture, a civilization that has proved its adaptability to crisis and persecution more than it has to openness.”

Dershowitz also believes those who aspire to high achievementâand its attendant visibilityâare reluctant to be pegged as overtly Jewish. “I think a lot of people want to transcend their Judaism,” he says. “They want to show they're bigger and better than that. If my onlyâquote, unquoteâ âsuccess' came as a Jew, I would think that I was limited. I didn't want to be a rabbi, after all. I wanted to be a lawyer who has influence around the world. But a very important part of me is being a

Jewish

lawyer.”

He stands up. “I gave a talk the other day in New York about what it means to be a âJewish lawyer.' I said, âSandy Koufax wasn't a Jewish pitcher. Nothing about his curve ball was Jewish. He was a Jewish pitcher because of something he

didn't

do: pitch on Yom Kippur.' I'm a Jewish lawyer because of what I

do

do: My teaching is very Jewish oriented. I know the Talmud; I use it all the time. I'm a well-educated Jew, which is another distinction. I don't feel uncomfortable with my Jewishness, because I know it.” And how would he describe it? The voluble professor actually pauses for a moment. “I've never found the right way of describing my Judaism,” he says simply. “It's very hard. I'm not a cultural Jew and I'm not a spiritual Jew. I'm Jewish the way my friends who are black are black. When I'm in the synagogue, I don't believe a word of it and I'm totally irreligious. When I'm sitting on the beach under the stars in Martha's Vineyard, I get a leap of faith.”