Stars of David (36 page)

And yet she says her Jewishness is integral to who she is. “I think it's really important. Not in a religious sense, but in the sense that I'm one hundred percent Jewish on both sides and I value the culture that it has given me. It's a great tradition to come from.”

And she understands why Jews tend to want to hold up their highest achievers, even after decades of assimilation and acceptance. “What we went through the last two thousand yearsâwith other cultures trying to get Jews to stop being Jews, to give up their faithâyou have to say, âOkay: This is what we get for that. What we get for that is the right to say,

Look

at who we are. Look who we have made ourselves. This is why it was worth it

. Yes, we paid in blood for refusing to kiss the cross or to eat pork and all of those things that for two thousand years the Christians made us do. But that's how we got Einstein. That's how we got Freud.'”

I tell her the conundrum for me is how Jewish identity survives if so many, like her, have steered clear of ritual and Jewish learning. What makes Jews Jews anymore?

“You know what makes Jews Jews anymore?” she answers. “The fact that the world won't let us forget. You can say till the cows come home that you're not a Jew, but the world keeps telling you that you are. And that's what makes you a Jew. What makes black people black? No matter how white your skin is, if you're a black person, the world keeps reminding you that you're black. Ultimately it's others' definition of us that makes us Jews.”

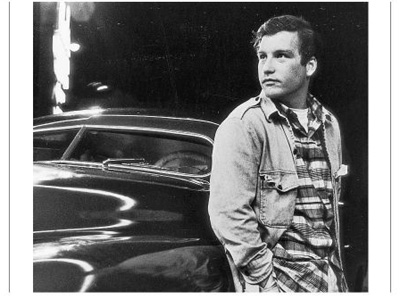

Richard Dreyfuss

RICHARD DREYFUSS DOESN'T AGREE with the notion that actors like him and like Dustin Hoffman broke the Hollywood mold of the leading man. “There's always been two parallel themes in movie stardom,” says Dreyfuss, sitting in gray sweatpants on a gray morning in his Upper West Side living room. “There's Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, and Robert Redford, and then there's Charles Laughton, Spencer Tracy, Edward G. Robin-son, and Jimmy Cagney. If there was a mold that was busted, whether it was Dustin, Barbra Streisand, myself, or a conglomeration of all three, it was that we said to the world, âWe're Jews. And we were very proud of that part of our story.' I don't rememberâbefore usâI don't remember anyone getting up and saying, âAnd by the way, I'm Jewish.' The generation before had basically said, âI'm going to change my name to Edward G. Robinson'; âI'm going to change my name to Danny Kaye.'”

Dreyfuss goes so far as to say he played up his Jewishness as a way to distinguish himself at auditions. “What I always tried to do was to separate myself; to create a story more interesting than the guy standing next to me. That's how I would be remembered and get the job. So part of my story was âJew.' Because no one else was saying it.”

Once he became famous, thanks to his roles in

Jaws

and

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

, not to mention his Oscarâthe youngest actor ever (until Adrien Brody in 2003) to win the best actor category, at age twenty-nine (for The Goodbye Girl)âhis Jewishness came up in press interviews. “It was a

thing

,” Dreyfuss recalls. “It was a known deal. And I liked that.” But he knew not to take the Jewish label too far. “There is always that problem: If you're an actor and you say that you're gay, you will not get heterosexual parts. You don't want to say you were raised in Beverly Hills, never went to college, and don't ride horses, because when you get the job of the Montana-born, Harvard-educated cowboy, they won't believe you. So there's always that element of, âDon't say you're Jewish, don't say you're short, don't say you're anything. Say you're everything.' That's the actor's oath. The actor's oath is, âCan I ride horses? Are you kidding? I was raised on a ranch!'”

Dreyfuss, fifty-eight, actually was raised in Beverly Hills from the age of eight, but he talks much more vividly about his earlier childhood in Bayside, New York. “Bayside was a hotbed of red-diaper baby, left-wing Jewish stuff,” Dreyfuss says, sipping bottled water. “We left Bayside when I was eight and a half, but it was still very resonant in me. I visit Bayside like I visit a synagogueâit really has quite a heavy aroma for me.” Politics

was

religion on his street. “If you had not been a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade [a volunteer organization that supported anti-Fascist forces in the Spanish Civil War], you better have a damn good reason,” he says with a laugh. Dreyfuss's memory this morning is being cross-checked by his sister, Cathyâfour years youngerâwho has just flown into New York after spending six months in Europe and who sits in on most of our interview sipping a café au lait.

These two siblings recall an unsubtle liberal upbringing, complete with union songs on the front stoop. “At ten o'clock at night in the summer,” Dreyfuss recalls with nostalgia, “my parents would come outside with their little deck chairs, my father would bring his guitar, and someone across the street would do the same thing with another guitar, and they would start to play these union songs or old Spanish Civil War songs. A guy in the neighborhood named Joe owned his own Good Humor truck.”

“Popular guy,” Cathy interjects.

“He brought his truck out on those nights,” Dreyfuss continues. “I can still see, in the pool of light from the street lamps, Joeâin his white uniformâgiving kids ice cream. And what you'd hear is,” Dreyfuss starts to sing robustly, “âThere once was a union maid' and âLast night I heard the strangest dream . . .' This left-wing texture was, well, up our nose,” he says with a smile. “And we were all Jewish.”

The Dreyfusses weren't observantâCathy hypothesizes that the Holocaust killed any notion of God in their homeâbut their dad insisted on some Hebrew school for his two boys. “When we moved to California, I was eight, my brother was ten, and Cathy was four,” Dreyfuss says. “One day, my father sat my brother and me down and said, âLook, I don't practice Judaism, but I feel that it is my obligation to introduce you to it. So I'm going to offer you two options; you have to do one of them, but you can choose which one. I'm not going to prejudice you in any way, I'm just going to describe them: One is bar mitzvah and the other is confirmation. Bar mitzvah is boring, it's stupid, you don't want to do that, it's dull, rote bullshit. But confirmation is where you discuss ethics and you debate and it's issues and it's history.'” Dreyfuss laughs at the obvious bias of this speech. “So I volunteered for confirmation. Little did I know that confirmation took seven years, bar mitzvah would have been only three. But I went. And I loved it.”

Hebrew school taught Dreyfuss early about the Holocaust. “It was, of course, our daily bread,” he says. Cathy recalls their parents warning them to always watch their backs. “They'd say, âNever feel comfortable. The Jews in Germany got too comfortable and look what happened.'”

Dreyfuss nods. “My father had a twinkle in his eye when he talked about politics,

except

when it came to the Holocaust and anti-Semitism. Then he got deadly serious.” Nevertheless, Dreyfuss says he never felt his father's fear. “I was so romantically involved with the story of the Jews in school, that to me anti-Semitism was this great compliment, this thing that obviously

little

people felt for

great

people. I was one of those secret liberal progressive Jews who believes thatâDreyfuss lowers his voice to a whisperââ

We are the Chosen People.' We are

. And even when that became not politically correct to say, I still do believe that.”

Dreyfuss says his acute pride came from the Jewish chronicle of endurance. “It's a miracle that an ethnic group could stay together, using the rigor of intellect and

seckel

[cleverness], and have no military strength for the overwhelming majority of their history, and see every civilization take the bullet but us. The Romans died, the Byzantines died, the Assyrians died, the Babylonians died, the ancient Greeks died, the Medievalists died, even the Church died in a sense. But the Jews consistently retained a set of principles and ties that bound one another. And that's a unique story.”

Dreyfuss regrets that he never conveyed that to his three children by his first marriage. “I had said to my first wife before we got married, âI'd like you to convert,'” Dreyfuss recounts. “I knew that I needed to re-create the atmosphere that I grew up with.” He says this was ill-conceived. “My first wife and I met under unrealistic circumstancesâI was just recently sober”âhe refers to well-publicized years of drug addictionâ“and we weren't asking each other really important questions. I said, âI want you to convert' and she said she would; then after we got married, she said, âNo, I won't.' So then I felt this overwhelming resentment. And then I became

really

Jewish. I mean, I began to be involved in Jewish politics, and the Israeli peace program, and stuff like that. I was so angry, I felt that my children had been kidnapped.

“It was made worse because I am naturally lazy and my Judaism can't be expressed by going to temple. It's just a generalized atmosphere that I grew up with and wanted for my kids: You jump into the pool and you're swimming around in Jewish water. So I wasn't going to demand that my children go to temple, but I wanted them to be in a Jewish household. It mattered a great deal, although the extent to which it mattered very much surprised me.”

After the divorce, his ex-wife moved with their children to Sun Valley, Idaho, and Dreyfuss remained in New York. “There was no reason for them to be Jewish on a daily basis after that,” Dreyfuss says dolefully. “Until then, they were Jewish just because I would come home and say, âJews! Come here!'” But he couldn't figure out how to maintain their identity from afar when he didn't buy into the rituals himself. “I couldn't force something long distance,” he says.

His sister, Cathy, rubs salt in the wound. “I would add,” she says, holding her coffee, “that from my perspective, there was something you had the opportunity to do but never made the effort to do, which would have made a big difference: making sure that the kids were brought to us for Jewish holidays. Our family has celebrated Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah, and Passover every year of our entire livesâeither at my place, Mom's while she was alive, or Uncle Gilbert'sâand

your

children have not participated.”

There's an awkward pause; I'm taken aback by Cathy's directness in front of a stranger. But her brother accepts the criticism. “I think that's what I mean when I say that I'm lazy,” he concedes. “I didn't understand the connection between Judaism and family until I was older. I didn't understand that going to High Holy Days services or going to Passover at my sister's was less about Judaism than it was about cousins. So yes, that was something that I certainly could have done and didn't; I didn't see the value of it at the time.”

He adds that his nineteen-year-old daughter, Emily, has recently shown an interest in her heritage. “She comes to it, oddly enough, as a tourist. To me, that's such a weird thing: My children are tourists about Judaism.”

Dreyfuss's second (and current) wife, Janelle Lacey, converted. “She did it on her own,” he says, “but she did it, to a certain extent, to please me. She kept kosher for two years, but she's since let that go.”

I can't help asking if his religion helped him in any way when he was going through “difficult times.” He cuts to the chase: “You mean like the drugs? No. Was I a

shanda

[a disgrace] to my family? I suppose . . .” Dreyfuss returns to the question of whether Judaism has ever been a comfort. “I think that's what's wrong with my life. I think I've always known that there was an aspect to life that was spiritual, and that one took comfort from it or dwelt in it and it answered some anxieties. But I have never known what that was. And it was not in Judaism; Judaism was too practical.”

Cathy gets up to get more coffee and Dreyfuss switches chairs. I ask him about the role that established him as a movie star in 1974:

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz

. He played an ambitious kid from the Jewish ghetto in Montreal whose moneymaking schemes get him into trouble. When the film came out, some Jewish audiences were offended by the character, which surprised Dreyfuss. “I was raised by people who I think were unflinchingly honest about their beliefs and who told the truth about being Americans, even if it hurt. We also told the truth about being Jews. So, to me, just as it was a shock to see that people didn't know about slavery until

Roots

was televised, just as it was a shock to find out that people didn't know about the Holocaust until the TV movie was made, it was a shock to find out that Jewish people didn't admit to Duddy Kravitz.

“To me, Duddy Kravitz was as normal as apple pie. He wasn't

the

Jewish character, but was he

a

Jewish character? Read Sholem Aleichem! Have

any

conversation about our history, and you know that our immigrant past can be basically summed up as: âquiet shtetl Jews sitting there for centuries being raped and pillaged and cheated, then they pick up one day and go to New York and hustle their little asses off until their children are in college.' And that hustle, which was first criminal and then civic and then business, is an epic and known story to the worldâor at least, to the Jewish world. So I read the original book,

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz

[by Mordecai Richler, 1959], and thought, âWow, this is the greatest part I've ever seen and I want this part so badly I could spit.' But I didn't know it was controversial until later.”