Stars of David (10 page)

Hewitt is even prouder of another letterâone that used to sit framed on his office bookshelf. “It's wrapped up somewhereâI can't find it,” Hewitt apologizes as he hastily leafs through his memoir,

Tell Me a Story:

Fifty Years and 60 Minutes in Television

, looking for the place where he quotes the letter, sent in honor of his seventieth birthday. Hewitt reads part of it aloud, in a hushed tone. It's perhaps his most compelling piece of evidence that he wasn't such a skimpy Jew after all:

“... As you know, your program is critically acclaimed throughout the world and is held in high esteem by many of us in Israel. I would also like to take this opportunity to express my personal gratitude to you for dedicating one of your

60 Minutes

segmentsâ the tragic story of our Israeli Air Force navigator, Ron Arad. Both as a Jew and a human being, I was touched by your coverage of his plight. I am deeply grateful to you and

60 Minutes

for all your efforts. As you enter your 25th year at

60 Minutes,

I wish you the best of luck and continued success in the future. Sincerely, Yitzhak Rabin; Prime Minister of Israel.”

Hewitt reads the signature with solemnity. “That letter is one of the proudest things I've got,” he says. “I think the terrorist who did the most harm in this worldâmore than Al Qaedaâwas the Jewish terrorist who killed Rabin.”

The phone rings and he picks it up. “Hello? Honeyâ” It's his wife, Marilyn. “I'm sitting here right now with Abby Pogrebin talking about being Jewish and reading her my letter from Yitzhak Rabin.” He relates Marilyn's reaction: “Marilyn says, â

You're

talking about being Jewish?'” He laughs. “Yes!” he tells her. “I'll call you back in a few minutes.”

Back to Israel: “I always admired Israelis. They were the gunslingers. They were great! Before it was politically incorrect to think about it that way, it was like the cowboys and IndiansâIsrael were the cowboys and the Arabs were the Indians and it was simplistic; I never knew anybody who rooted for the Indians. I always thought the Israelis were arrogant as hell, but I admired them. But I never understood why the smartest people on earth plunked themselves down in the most hostile place on earth. They could have found a better place. They could have gone to Madagascar or something. But they say, âIt's the land that God gave them.'

Who the heck

knows what God gave anybody?!

How do they know that? I think it would be a big loss to civilization if Israel disappeared. I just wish they'd get off all this jazz about âGod gave us this land'; God didn't give you the landâyou

took

the land and you made it great! And I love you for doing that, but don't tell me that God gave you this land and he doesn't want anybody else here.

“I'll tell you my favorite phone call: One time, a woman called after we aired a story on Israel. And she said, âI'm getting sick and tired of you people.' I said, âOkay lady, what now?' She said, âYou're all pro-Israel, and you're all a bunch of kikes.' I said, âOn your first point, you couldn't be more wrong; on your second point, you could be right.' And I hung up on her.”

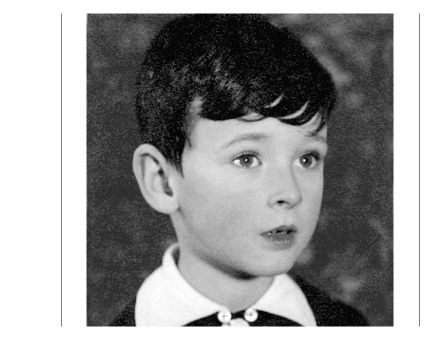

Mike Nichols

DUSTIN HOFFMAN TOLD ME that when he auditioned for

The Gradu

ate (1967), the director, Mike Nichols, told him that the WASPy character of Benjamin Braddock was “Jewish inside.” When I ask Nichols what he might have meant by this, he says his answer can be found in a Thomas Mann story. “Did you ever read

Tonio Kröger

?” he asks me. (I didn't.) “It took place in Germany one hundred years ago and it was about the blond, blue-eyed people and the dark people. The dark people were the artists and the outcasts. And the blond, blue-eyed people were at the heart of the group and were the desired objects.” I see where he's going: Benjamin's an outsider, so he's metaphorically Jewish.

“There would have been two ways to cast and direct

The Graduate

,” Nichols continues. “One is to have Benjamin be a sort of a walking surf-board, which is the way the novel is written, roughly. And the other is to express his difference from his Californiate family and their friends. And only semiconsciously, I think, did I pick the latter. At the time, it was just that no actorâI saw hundreds, if not thousandsâof young actors, and nobody was quite there, nobody was quite right, and it was getting desperate; not only had we seen every young actor, but we'd seen every young

janitor

by that point.

“I said, âThere is a very talented young actor that I saw in an off-Broadway play in which he played a Russian transvestite'âI still remember him cutting up fish on a butcher block wearing a dress. And I said, âI'd like to see that guy; let's see if we can get him to come out to L.A.'” Needless to say, Hoffman got the part. “Of course, when we saw the film it was clear that this was Benjamin, nose and all,” Nichols says with a smile. “And it's not that the piece was transformed, it was that the piece was

achieved

, but in a way that we would never have guessed.” In other words, the un-Redford Jew clinched the disaffected WASP.

We're sitting in the airy, book-lined living room Nichols shares with his wife, ABC News anchor Diane Sawyer, on Martha's Vineyard. We've retired to this room with tall glasses of ice water after a generous four-course lunch that included taro tuna rolls, gazpacho, and strawberry lemonade. It's August, and a gentle breeze glides in off the bay through open doors. Nichols is tan but not dressed for this seasonâhe's in long tan pants, long-sleeved black shirt, and loafers. It's too facile to draw a metaphor from his attire, but I can't help it: This comedic director is darkly dressed for a sunny summer day and it reflects something he's alluded to often in old interviews, a sense of being a fish out of water, the way he described Benjamin Braddock. I ask whether he relates this outcast feeling to his Jewishnessâto his childhood experience of escaping Nazi Berlin in 1939 as a seven-year-old (he traveled alone with his four-year-old brother, with a “stewardess” looking after them).

“This is tricky,” he begins, taking a sip of water, “because I think there are two different things: One is Jewishness and one is refugee-ness. The second one being something you might call the âSebold Syndrome,' if you read

The Emigrants

. Did you?” (No; I'm a shamed English major.) “You remember the themeâthe Sebold experience: namely that your guilt about the Six Million finally comes and gets you . . . That was what that book was about. Everyone in it in a different way finally couldn't bear having survived. And if you're a refugee, and if things came that close, that's something you push away and push away and push away until it comes and gets you. There's just no question about it. And after that ton of bricks hits you, then you've got to do a lot of work, both inner and active, in the sense of doing something

for

other people, in order to go on. By definition, whether you are a refugee or not, you are a member of a group that has been hated by a large number of people through all history. It's impossible not to be aware of that hatred. And puzzled by it and amazed by it and appalled by it, sometimes joining itâto your own horrorâand jumping out again as fast as you can.”

He offers an example of when he momentarily “joined” the scorn for his own people: “I once said to Jerry Robbins [the director and choreographer of

Fiddler on the Roof

and

West Side Story

], âI'm worried that all the great monsters of narcissism in show business are Jewish.' And I named some names, which I won't do now. And there was a long silence, and he said, âYes, well: Mickey Rooney.'” Nichols laughs heartily. “I said, âOh, thank you; thank you. That feels better.'”

Nichols laments the fact that Jews can't give themselves a poke in the ribs every once in a while. “You know what the problem is, among many other things? Correctness. Correctness was such a blight on humor and the truth. One of the joys of

The Producers

was that every possible correct position was exploded, and you just sat there howling and grateful. It was the death of correctness in a way.”

Nichols's outsiderness was seeded when he was still Michael Igor Peschkowsky in Berlin, attending a segregated Jewish school; he doesn't remember being given any explanation for it. “I'm pretty sure I was simply told that Jews were required to attend school separately from Aryans,” he says. As Berlin became more acutely inhospitable to Jews, his family knew they had an escape hatch. “The reason that we got out is that my father was Russian and we had Russian passports, and it was during the two-year Stalin-Hitler Pact. That's what saved our lives.”

Still, getting the paperwork was arduous. “A long time was spent sitting in consulates hoping for a visa,” Nichols recalls. “Very few people seem to know this, but do you know what you needed financially to get into this country?” I shake my head. “Every individual had to have someone guarantee them financially

for the rest of their lives

. We were a family of four; each one of us had to have a specific financial guarantee for our lifetimes. And luckilyâto put it mildlyâmy mother had a cousin with money, who was already in the United States. And he did it. But without that, you couldn't get a visa. It's not exactly â

your huddled masses

.' But nobody knows this. Some people know about Roosevelt turning the

St. Louis

back. But very few people know this.”

He's referring to the incident in May 1939 when the S.S. St. Louis, filled with 937 Jews fleeing Germany bound for Cuba, was not permitted to land on American shores. F.D.R.'s Secretary of the Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., who was Jewish, argued to the president that the ship should be welcomed, but Roosevelt refused, and the

St. Louis

turned back to Europe with its passengers, many of whom went on to perish in the Holocaust. “I was talking to Spielberg about this,” Nichols continues (in fact, Spielberg had flown to the Vineyard for a visit just the day before), “and saying to him that people keep making not-very-good movies about the

St. Louis

, but that the

real

movie, it seemed to me, is about Morgenthau. The only Jew in Roosevelt's administration who presumably started out saying, âMr. President, you have a chance to do something wonderful; we have a chance to do something really important,' must have gone close to insane at the end of the week when the

St. Louis

was sent back, realizing that Roosevelt didn't care at all.”

Nichols remembers his own arrival at New York City's shores, at the age of seven. “When we got off the boat in New York, there was a delicatessen right near the dock and it had a neon sign with some Hebrew letters in it, and I said, âIs that allowed?' So at seven, I had some sense of what that would have meant back in Germany.” Despite his childhood English lessons, Nichols could barely communicate. “I only had two sentences: âI don't speak English' and âPlease don't kiss me.'”

Nichols's father, a physician, had come to New York ahead of his family to take the American medical exams and start his practice. “My father changed our name the week he became a citizen. Because his name was Peschkowsky and he said that by the time he would spell his name, the patient was in the hospital,” Nichols smiles. “âNicholas' was his patronymic [the name derived from one's father, in this case, Nikolayevich Peschkowsky]. I've been accused often of changing my name, but I didn't.” Only five years after Nichols arrived, his father succumbed to leukemia. His mother, who had stayed in Germany after they left because she was ill, joined her boys in America a few years before her husband died. “She, who had never had a job, learned English and supported my brother and me,” Nichols says.

All this time, they observed no Jewish rituals whatsoever. “No one in my family would have known

how

to have a Jewish holiday,” he says with a laugh. “Nobody in my family knew anything about it, and yet you could hardly say they weren't Jewish.”

He explains that his mother's parents were well-known German writers whose Jewishness was not based in synagogue at all. “My grandmother [Hedwig Lachmann] wrote the libretto for

Salomé

with Richard Strauss, which she translated from Oscar Wilde's French. And so she was a pretty well-known poet. And my grandfather [Gustav Landauer] was a writer who had written many books, and along with Martin Buber, was one of the first people to work toward creating a Palestine. But they were a kind of Jewish that didn't exist after that in Germany. That is to say, ideologically they were very Jewish, but they did not speak Yiddish, they didn't observe any of the holidays. They were not Jewish in any perceptible way.”

Still, Nichols is surprised that he didn't pick up any Yiddish in his childhood, since it was so close to his native German. “Elaine May and I used to speak Yiddish in our show. We used to improvise stuff based on suggestions from the audienceâwe'd ask for a first line and a last line and a style. And one night an audience member gave us âYiddish theater.' Now, Elaine was raised in the Yiddish theater; her father was at the time a very famous Yiddish actor. So she did a very sophisticated sort of Yiddish thing. She came in with a cigarette and said âTata!,' sort of like Bette Davis. She was very hip. And I was beside myself. Finally I just gave up and I spoke Yiddish. Because under pressure, you can do strange things. And it came out. It wasn't exactly a miracle, because I spoke and speak German. I didn't know Yiddish, but I had to, so I spoke it. But that's as far as I ever got with Yiddish or any Jewish holidays.”

Just as there were no Jewish rituals in his family, there was no Jewish pressure to marry a Jewish girl. Nichols's four marriages have been interfaith. “My mother was not Jewish in any of those senses,” Nichols says. “She was very guilt-provoking, but I don't know that that counts.” It certainly paid off in one of the most famous Nichols and May skits, “Mother and Son,” where May played the neglected mother and Nichols the guilty son. “When Elaine and I were a comedy team, we had a very central and successful sketch that was about a Jewish mother. And the way it came about was that we were already working in New York, and one day my real mother called me and said, âHello Michael, this is your mother; do you remember me?' And I said, âMom, can I call you right back?' and I hung up and I called Elaine and I said, âI have a new piece for tonight,' and I told her my mother's line, and she said, âGreat.' And we

never

said any more about it, but we did the piece that night and it started that way.

“The Jewish mother that Elaine played was so horrifyingly recognizable, so familiar, and so hilariously guilt-provoking.” He offers an example: “She [Elaine, playing the mother] was complaining that I never called. She said she hadn't eaten because she didn't want to take the chance that her mouth might be full when her son finally called. I would say, âI was busy sending up the

Vanguard

, mother'âwhich was a rocket at the timeââI didn't have a second'; she said, âWell it's always something.' And then finally, she said, âI hope I haven't made you feel bad.' I said, âAre you kidding? I feel awful.' And she said, âOh, honey, if I could believe that, I'd be the happiest mother in the world.' She said, âSomeday, Arthur, someday you'll have children of your own. And when you do, I only pray that they make you

suffer the way you've made me suffer

. That's all I pray. That's a mother's prayer.'