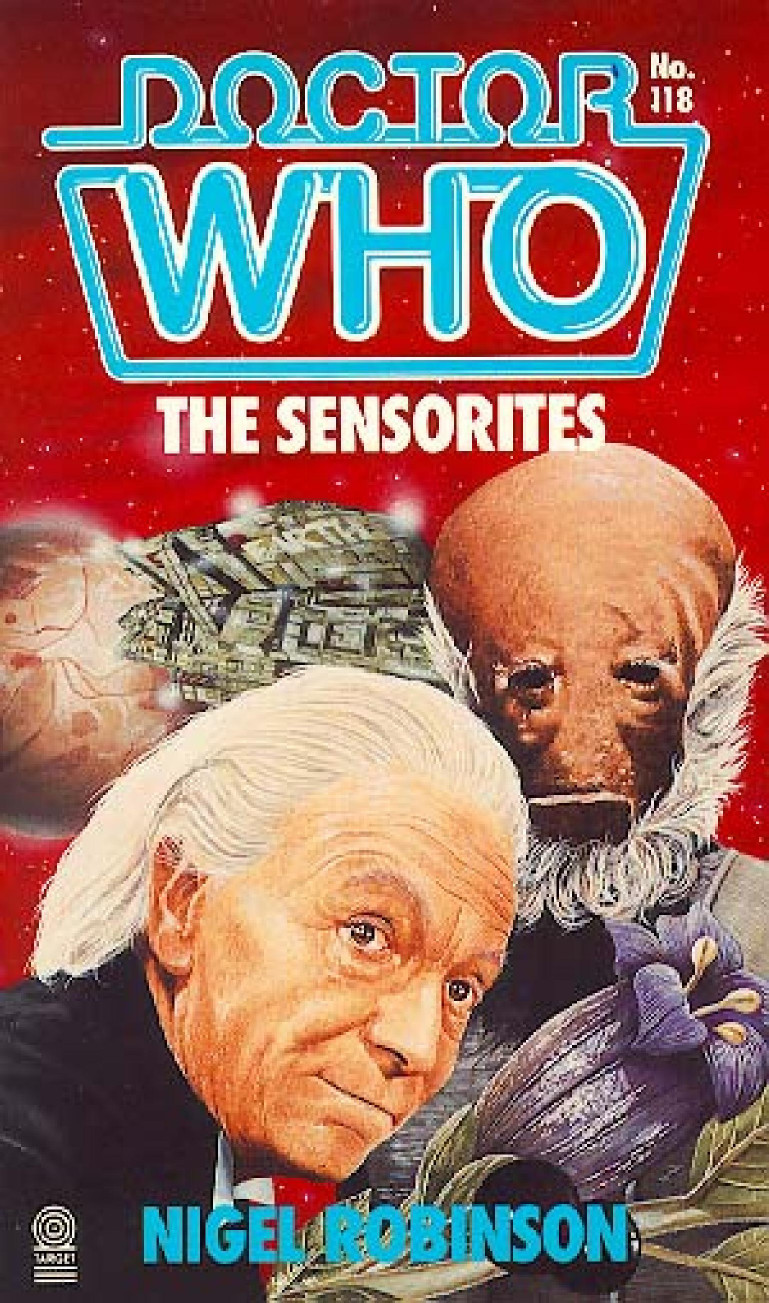

Doctor Who: The Sensorites

THE SENSORITES

NIGEL ROBINSON

Based on the BBC television series by Peter R. Newman by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation

Number 118 in the

Doctor Who Library

A Target Book

Published in 1987

By the Paperback Division of

W. H. Allen & Co. PLC

44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB

Â

Out in the still

and infinite blackness of uncharted space, hundreds of light years

from its planet of origin, the spacecraft hung, caught like a fly in

a gigantic spider's web. Here in the outermost reaches of the galaxy

few stars shone; what little illumination there was came from the

bright yellow world around which the ship moved in perpetual orbit,

and that planet's mother star.

If there had been

human eyes to watch, they would have recognised the ship as an

interplanetary survey vessel, one of many sent out from its home

planet in the early years of the twenty-eighth century to search for

new sources of minerals to replace those long since squandered on

Earth. Nearly a fifth of a mile in length and with its dull grey hull

studded with innumerable scars, the result of thousands of meteor

storms encountered in its four year journey, its survey had been

almost complete when it entered this region of the galaxy; and now

here it remained, a ghost-like satellite in the planet's otherwise

moonless sky.

Along the cold and

empty corridors of the ship all was still, save for the occasional

tinkling of an on-board computer and the steady rhythmic pulse of the

life support system. Otherwise a ghastly silence reigned, as

impenetrable as stone and as quiet as the dark and lonely grave.

The crew's

quarters, the recreational areas, even the power rooms and

laboratories were also empty and shrouded in semi-darkness. All

unnecessary power had long since been reduced automatically to a

minimum: where there were no living creatures there was also no need

for light.

Upon the flight

deck, once the hub of all activity on board the spaceship, the same

all pervasive stillness was supreme. By the navigation and command

consoles, their forms half-hidden in the baleful light of the

scanners, sat two motionless figures - a man and a woman. Dressed in

the same one-piece military grey

tunics, they were slumped over their respective control boards, their

ashen faces totally oblivious of their surroundings, or of the

digital read-outs displayed on the computer screens above their

heads.

A single blinking

light on a control console indicated that the ship was in flight,

continuing its interminable and purposeless orbit of the yellow

planet. But there was no one on board the ship able to acknowledge

its futile warning, nor to take any action to alter the spaceship's

course.

To all intents and

purposes, it was a ship of dead men, going nowhere.

Strangers in Space

In the dazzling

expansive surroundings of a control room which boasted instruments no

one on twenty-eighth century Earth could even have dreamed of, the

four people around the central control console seemed strangely out

of place. As out of place, in fact, as the antique bric-a-brac which

crowded the room.

The youngest of the

four was a teenager, dressed in the style of clothes common to Earth

in the 1960s. No longer a girl, and not yet quite a woman, her

closely cropped hair framed a face of almost Asiatic prettiness, and

her dark almond eyes belied an intelligence far beyond her tender

years. Her companions were all turned intently towards the flickering

instrumentation on one of the six control panels of the central

console. She, however, looked enquiringly at the puzzled face of the

silver-haired old man, from whose side she seldom strayed and whom

she trusted implicitly.

'What is it,

Grandfather? What's happened to the TARDIS?' she asked, her tone

wavering as she tried hard to conceal the inexplicable sense of

unease she felt within herself.

The old man looked

up. 'I really don't know, my child, I really don't know,' he said,

tapping the fingers of his blue-veined hands together as was his

habit when faced with a vexing problem.

He wore a long

Edwardian frock coat, checked trousers, a crisp wing-collar shirt and

a meticulously tied cravat. He seemed every bit the image of a

well-bred English gentleman of leisure rather than the captain of a

highly advanced time and space machine.

Turning to his

other companions he drew their attention to the tall glass column

which now rested motionless in the centre of the hexagonal control

console. 'All indications are that the TARDIS has materialised. But

that' - and here he pointed to one

persistently flashing light on the control board - 'says we are still

moving. Now, what do you make of that, hmm?'

The third member of

the TARDIS crew spoke up, a tall tidy woman in her late twenties,

with a stern purposeful face which nevertheless possessed a

melancholy beauty. Like Susan she too dressed in the fashion of late

twentieth-century Earth, though her more conservative clothes

reflected her maturer years. 'Perhaps we've landed inside something?'

she suggested. 'Perhaps that's why we appear to be moving? What do

you think, Ian?'

'You could be

right, Barbara,' agreed the stocky well-built young man beside her.

He spoke to the old man: 'Try the scanner again, Doctor; let's see

what's outside.'

The Doctor

activated a switch and the four travellers looked up at the scanner

screen, set high in one of the roundelled walls of the control room.

The picture on the screen was nothing but a blanket of random flashes

and lines.

'Covered with

static,' observed the Doctor.

'That could be

caused by a strong magnetic field,' Ian ventured.

'Yes. Or an

unsuppressed motor,' agreed his older companion.

'Can we go outside,

Grandfather?' asked Susan.

The Doctor allowed

himself a small smile, recognising in his granddaughter the same

insatiable curiosity which had caused them to begin their travels so

very long ago. He nodded his assent: 'I shan't be satisfied till

we've solved this little mystery.'

By his side,

Barbara sighed. 'I don't know why we bother to leave the TARDIS

sometimes,' she said gloomily.

'You're still

thinking about your experiences with the Aztecs,' remarked the

Doctor.

Barbara's mouth

formed a rueful half-smile. 'No, I've got over that now,' she said,

recalling a previous adventure in fifteenth-century Mexico. There she

had unsuccessfully attempted to put to an end the Aztecs' barbaric

practice of human sacrifice. The Doctor had watched her struggle with

wry admiration, knowing all the time that no mortal man could ever

halt the irreversible tide of history. The Aztecs had practised human

sacrifice and nothing that Barbara or even he - travellers out of

time - could do would ever alter that immutable historical fact. The

Doctor had long ago come to terms with the futility of attempting to

change history, but Barbara could never stand back and watch her

fellow creatures suffer. Cold scientific observation was all very

well, but it meant nothing if not tempered with human compassion and

love.

But she would

eventually accept the strictures placed on travellers in the fourth

dimension, thought the Doctor. Yes, Barbara and Ian would learn from

their fellow travellers, just as he and Susan would learn from them.

The Doctor paused

for a moment to recall his first meeting with Ian and Barbara.

Teachers at Coal Hill School in the London of 1963 and curious about

the background of their most baffling pupil, they had followed Susan

one foggy night to an old scrapyard in a shadowy road called Totters

Lane. There they had finally met the girl's grandfather and guardian

- an intellectual giant known only as the Doctor, an alien cut off

from his home planet by a million light years in space and thousands

of years in time. And there too they had stumbled across the secret

of the TARDIS - a craft of infinite size, capable of crossing the

dimensions of time and space, and housed in the impossible confines

of a battered old police telephone box.

Originally

unwilling fellow travellers, Ian and Barbara had grown fond of their

alien companions, as had the Doctor and Susan of them. And though at

times the two teachers -Barbara especially - thought longingly of

returning to their own planet, their journeys through time and space

still inspired in them a great pioneering spirit; what had started so

long ago as a mild curiosity in a junkyard had now turned into quite

an exciting adventure.

The Doctor applied

himself once more to the problem in hand. With an experience born of

countless journeys, his eyes dashed quickly over the dials and

digital displays on the console. Satisfied with the read-outs from

the TARDIS computer, he turned to his granddaughter. 'Open the doors,

Susan,' he commanded.

'You've checked

everything then, Doctor?' asked Ian.

'Of course I have,

Chesterton,' he replied peevishly. 'Plenty of oxygen and the

temperature's quite normal.'

'So there's just

the unknown then,' said Barbara.

'Precisely!'

Susan operated a

small control on the console. With a gentle hum the great double

doors opened. All four travellers felt the same thrill of

anticipation they always felt upon entering a new world. What would

lay waiting for them beyond the doors?

The police box

exterior of the TARDIS had materialised inside a long shadowy

corridor. But for the large circular doors which periodically

interrupted the ridged aluminium panelling of the walls, the

time-machine might just as easily have landed in an underground

tunnel: everywhere there was the same claustrophobic sense of doom

and menace. Indeed, the air seemed as stale and musty as the air of

any tunnel could. There was no sound to be heard.

'You were right,

Barbara,' said Ian; 'we have landed inside something.'

'It's a spaceship!'

exclaimed the Doctor triumphantly, satisfied now that the mystery of

the TARDIS's apparent motion had been explained. 'Close the doors,

Susan,' he said to his granddaughter, and then addressed his other

companions: 'Let us be careful: there seems to have been some sort of

catastrophe here.'

With the TARDIS

doors securely locked, the crew ventured cautiously down the

spacecraft's grey corridor. The design of the ship seemed to be

solely functional and was devoid of any decoration or colour. Whoever

the ship's crew might be, thought Barbara, they must be very dreary -

or extremely dedicated. But as she walked down the long passageway,

almost wading though the oppressive silence, she began to wonder if

the ship was inhabited at all; perhaps it had been abandoned years

ago, left to drift through all eternity like a Maty Celeste of space?

The Doctor had

considered it wise to keep to one corridor, rather than pursue any of

the connecting passageways or doors, and after some minutes the four

friends came upon what they took to be the spaceship's main flight

deck. Here the gloom was

dispersed somewhat by the illuminated screens set around the walls,

and the view of a bright yellow planet through the observation port.

Several banks of computers lined the walls and they chattered away

spasmodically to each other. But other than that the place was dead:

no movement, no life, nothing.

It was Ian who

first saw the two bodies. Rushing over to the man, he raised his head

from where it had slumped onto the control panel, and felt for a

pulse. Nothing. Shaking his head, he returned to the others, one

heavy word on his lips: 'Dead.'

'Look, this one's a

girl,' cried Susan, going over to the body at the navigation console.

Barbara quickly

joined her and, like Ian, checked for signs of life. 'I'm afraid

she's the same,' she sighed. 'What could have happened to them? I

can't see a wound or anything.'

'Suffocation,

Doctor?' ventured Ian.

'I never make

uninformed guesses, my friend,' said the Doctor, tapping his coat

lapels, 'but that's certainly one possibility.' He looked down at the

dead girl's face. Her fair hair was piled in disarray on top of her

head, but there was still a prim beauty about her. 'Such a great

tragedy. She's only a few years older than Susan.'

While her

companions had been examining the bodies, Susan had stood back,

feeling once again that strange sense of unease she had experienced

before in the TARDIS. It wasn't the fact that these two young

astronauts were dead; she had seen death before, in many gruesome

forms. But this was something different, inexplicable. It was as if a

thousand voices were shouting in her head, telling her to get off

this ship of dead men while she still had the chance. 'Grandfather,

let's get back to the TARDIS. Please . . .' Her voice trembled.

'Why, my child?'

asked the Doctor, looking up from the dead girl's face.