Stars of David (12 page)

But not the heads of congregations. Perelman sighs when I ask how he feels about women rabbis. “You know, you start getting into real issues there, because you get into who can read the Torah. And I, for one, am a purist.” In other words, women shouldn't. “I feel most comfortable that way.”

An avowed traditionalist, he wasn't thrilled at the bar mitzvah of Ellen Barkin's son, when the customary rites were relaxed. “When my stepson was bar mitzvah at Central Synagogue,” he explains, “he read from the Torah, his mother got an

aliyah

[the blessing over the Torah], and his

father

got an

aliyah

. His father [Gabriel Byrne] is not Jewish! True, they didn't give him a

bruchah

âthey gave him just a “come up to the

bimah

.” But here you have a non-Jew standing on the

bimah

! Which I thought wasn'tâ” He looks for the right word. “That kind of thing bothers me. I think that's one of the reasons that you see the Reform movement waning and the Orthodox movement growing. I think the Jewish youth of America looks at it and says, âWhat is this? It's so diluted that it's meaningless.'”

Since intermarriage is considered another dilution by many Jews, I figure I'll ask a veteran: Does Perelman, who was once married to a Catholic, think differing faiths can be negotiated in a marriage? He's more forthcoming than I expected. “I'll give you my point of view.” He leans forward. “I happen to have been married four times: three to Jewish girls and one to a gentile girl who converted to Judaism in an Orthodox conversion, prior to our getting married and to our child being born.” He's speaking of Patricia Duff, the striking former Bill Clinton fund-raiser who was married to Hollywood producer Mike Medavoy before Perelman. “What I can tell you is that the difference in orientation was very significant,” Perelman says, “as was the view of family and kids and life. I'm not saying one's right and one's wrong because there's no right and wrong in thisâbut it's different. It's like being an electrician or being a plumber; they're both good things, but they're different. I think it makes it very, very difficult for the couple.” He pauses. “And I think it makes it very, very difficult for the kids of that couple to know who they are and what they are. There's enough that we all have to deal with. That's not a burden that should be put on a relationship. This is a very personal point of view.”

He's shared his perspective with his older children. “I've constantly said how important it is to me and to them to marry a Jewish spouse. And they sort of get it. I don't think they think differently.” Although they don't let him forget he once broke his own rule. “Once in a while, jokingly, they'll say, âBut what about

you

?' I'll say, âWell, she converted!' But they saw the problems too.”

The “problems” boiled over when Perelman and Duff split. Newspapers obsessively chronicled their custody battle over Caleigh, a standoff Perelman ultimately won. There was the tidbit that Duff sought $1.3 million a year in child support, Perelman's stipulation that Caleigh be raised as a Jew, and reports that Duff had baked cookies with Caleigh during Passover week, a period when no leavened food, such as flour, is to be touched.

Today, Perelman describes Caleigh as a conscientious Jew who will likely be bat mitzvah, although he says he won't insist upon it the way he did for his older boys. “For the Orthodox, it's not required for girls,” he says. “In fact in Orthodox observance, there's not really a service.”

Though Perelman's standard of Jewishness is high, he is surprisingly forgiving of those Jews who don't practice at all. “I'd like it to be different because I think it does them and their familiesâparticularly their childrenâ a disservice. It bothers me when you see Jews go out of their way to be so assimilated. But they're still Jewish because they're born Jewish and they feel the pride of being a Jew.”

And he thinks that counts? “It doesn't count for me,” he acknowledges. “Because I need more than that. I actually think if they were exposed to it, they'd want more than that too.” But Perelman acknowledges that he's an exception among his friends. “They're not like me,” he says. “But some of them are. And when I go to synagogue, they

all

are. And they look at

me

and say, âYou're not religious

enough

.'”

And when he sees a Hasid on the street, does he feel connected or alienated? “I feel neither,” he replies. “I say to myself, âThere's another Jew.'” He gestures toward me. “Just like you; you're another Jew. I just say, âThere's another Jew.'”

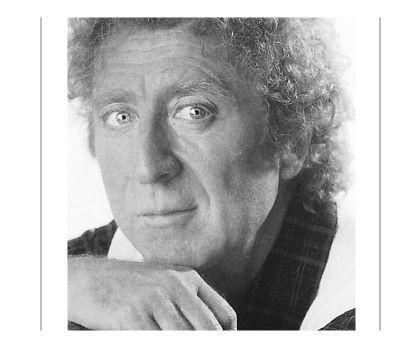

Gene Wilder

HE MENTIONS GILDA right away. I thought it was a subject I'd have to work up to, but I haven't been inside his eighteenth-century Connecticut home for ten minutes before he tells me it was hers. She bought it to escape show business. It's also where she was planning to recover. “Gilda and I moved back from California thinking that she was cancer-free,” Wilder says with his famously soft voice, “and then three weeks later she found out it had come back.” Despite the fact that he's happily remarried for the fourth time to a hearing specialist named Karen, whom I hear him call “Shug”âas in “Sugar”âGilda seems to accompany him like a spirit. “She's buried out here,” he says, gesturing vaguely to the grounds.

It's an undeniable thrill to meet Willy Wonka in the flesh. I spent so many childhood hours watching him in his purple velvet coat and top hat, sipping from an edible flower, entreating Augustus not to drink from the chocolate stream; to this day I know his every inflection. And here he is before me, the man who was at one time the highest-paid film actor in America, the famous flyaway hair even more wispy, blue eyes just as blue, that small smile that barely curls the lips upward. In person, however, it's clear he's not just “The Candy Man”; his face reveals the Comic with a Requisite Life of Sorrows. Despite his current good health and good marriage, despite all the laughter he's engendered in classics such as

The Producers, Young Frankenstein

, and

Stir Crazy

, the sadness or weariness is evident, and for good reason.

His mother died when he was fourteen. His second wife's daughter, whom Wilder adopted, is estranged from him. His great love, Gilda Radner, died only five years after their wedding in 1984. Ten years later, he was diagnosed with non-Hodgkins lymphoma, which he's managed to fend off. When we meet, he's nursing Karen's mother through her dying days under their roof. I ask him whether Judaism has helped him through any of these hard times and he shakes his head. “I think Freud got me through,” he says. “When I was in desperate trouble for maybe eight or nine years, I went to a neuropsychiatrist.”

We're sitting on a weathered orange-red leather sofa in his officeâa haphazard but inviting room that looks like it has accumulated things over the years without any real plan. There's an upright piano, a quilt draped over the piano seat, purplish wall-to-wall carpeting, a Macintosh computer on a wooden desk, videotapes on a shelf, and one or two of Wilder's own watercolorsâsurprisingly skilledâon the walls.

“I'm going to tell you what my religion is,” Wilder announces, leaping to the point. “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Period. Terminato.

Finito

.” (I can't help hearing Wonka's voice in the factory: “

Finito!

”) “I have no other religion. I feel very Jewish and I feel very grateful to be Jewish. But I don't believe in God or anything to do with the Jewish religion.”

Wilderâformerly Jerome Silbermanâsays his Jewish background consisted of attending an Orthodox temple where his grandfather was president. His sister and mother had to sit separatelyâ“not being equal to men,” he jokes sardonically. His father was born in Russia, his mother in Chicago, of Polish descent, and neither was particularly observant. But he was bar mitzvahedâ“I don't know to please whom,” he says. “I practiced singing the

maftir

a year before my bar mitzvah,” he says, referring to his designated Torah portion. “And I was so distraughtâbecause I had a high soprano voice and no one could hear me in the temple when I started to sing. So I said, âI'm not going to be bar mitzvah if you don't have microphones next year!' And they put the microphones in. And then, of course, my voice changed.”

His father switched the family to a Conservative synagogue when they moved to a new neighborhood in Milwaukee, but Wilder jettisoned the temple visits altogether when he was offended by the rabbi. “I went back to visit Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and heard the ignorant rabbi giving his views on the Vietnam War, and I wanted to get up and start hollering at him. But I thought, âMy mother and father will be embarrassed and their friends will say,

Why did he do that

?' So I didn't. But that's the last time I went to a temple.”

When I ask whether Wilder was conscious of being in a minority growing up, he tells a doleful story. “My mother was very ill and she had heard from distant relatives that there was a military academy in Los Angeles [the Black-Foxe Military Institute]. And she talked my father into sending me to the military academy to stay there for a year. And I got so excitedâI thought we'd be playing war games. I got there and I was the only JewâI was thirteenâand they beat me up or insulted me every day that I was there.”

He tells me he fought back only once. I ask what happened. “I got beat up,” he replies flatly. “They didn't hit my face: They'd make my arms black and blue, so when I came home for Christmas vacation, I was wearing long sleeves and my mother didn't know right away. My mother had thought I was going to learn about sex, and how to play the piano, and bridge, and how to dance. I think she'd seen Tyrone Power in

Diplomatic

Courier

. She asked me to play something on the piano and I played âNobody Knows the Troubles I've Seen' very badly. It was so bad and she was so disappointed, she walked out of the room, which was a cruel thing for her to do. And when I changed for dinner, I took off my uniform shirt and she walked in and saw all the bruises all over my body. And I started to cry. She'd had no idea. I'd written to my father, but he hadn't told her. And she just held me.” Wilder's voice has gotten quieter. His parents pulled him out of the school.

That wasn't the last of the childhood hazing. He was mocked in junior high school, and he reproduces the jeering so quickly, I realize it's at the tip of his memory. “âHey, Jew Boy! Why don't you ask the Jew Boy?'”

I remark that this experience must have had some kind of impact. “I don't know how it could

not

have,” Wilder allows. “But again, I didn't associate it with any religious philosophy; only the fact that I was something called âJewish' and why did they hate me just because of it? I was always afraid to talk about the teasing at home because my mother was so ill.”

He felt no anti-Semitism once he started doing theater, but he changed his name anyway, when he was twenty-eight, as so many actors did. “It was 1961; I'd just been admitted to the Actor's Studio. I'd been studying with Lee Strasberg in private classes using my name, Jerry Silberman, and I didn't want to be introduced to Elia Kazan, Paul Newman, and Shelley Winters as âJerry Silberman.'” He consulted a friend on possible alternatives and seized on “Wilder” because Thornton Wilder's

Our Town

is his favorite play. “Gene” was chosen because he loved the lead character of Eugene in Thomas Wolfe's play

Look Homeward, Angel

. He didn't connect that it echoed his mother's name until he was in therapy years later. “I was telling my analyst and she said, âUh huh . . . By the way, what was your mother's name again?' Dot dot dot dot . . . And I said, âJeanne.' [He spells it.] J-E-A-N-N-E. I'd never thought of that.”

The only one who still calls him Jerry occasionally is his sister. I ask him if that name feels like him anymore. “When she says it, yes. But if someone hollered out âJerry,' I probably wouldn't turn around.”

I ask him how it felt to play two classic Jewish film roles and he holds up one finger: “You mean one,” he corrects me: “In

The Frisco Kid

.” But what about Leo Bloom in

The Producers

? I ask. “Oh! Oh!” Wilder says with a smile, “I never thought of that. I suppose so. I never thought of it. Of course, Leo. Well, because Zero and Mel

made

it Jewish. But there was nothing overtly Jewish in the writing. Well actually, I can't say that either because the way Mel writes, it

is

Jewishy, but not filled with Jewishisms.”

Leo Bloom in

The Producers

(1968) is the uptight accountant who conspires with a failing Broadway producer (Zero Mostel) to produce a guaranteed flop. In

The Frisco Kid

(1979), Wilder played on Orthodox Polish rabbi in the 1850s, Avram Belinski. Complete with long black coat, thick beard, and black hat, Belinski schleps his prized Torah across the plains on a grueling journey to his new congregation in San Francisco. The naive rabbi undergoes myriad hardships, several of which involve being mercilessly assaulted, until he hooks up with a tough cowboy, played by Harrison Ford.

Wilder needed to supplement his scant Jewish education to prepare for the role, so he hired two rabbis and a cantor. “The cantor recorded prayers for me on the tape recorder,” Wilder explains, “and I had to study to be able to sing them. Everywhere I went I had that recorder. Then for technical advice, I consulted one Conservative rabbi and one Reform rabbi. Just to answer questions for me. But the cantor was the most helpful. The idea of singing in Hebrew on-screen was something I would have instinctively rejectedââHow am I going to do

that

?' But when I heard it on the tape recorder and I could repeat it and I knew what the words meant and the phrasing, and I could make it my own, then I could do it.”

I ask him if that role made him think about being Jewish. “A lot of it did come easily,” he answers. “I wrote a lot of that movie. Not the prayers, I mean,” he says with a chuckle, “but the dialogue. When I was writing I was thinking, âWhat would be funny for a rabbi to do?' I didn't think, âWhat would be funny for a

Jew

to do?' I know I'm saying the same thing, but in my mind, it wasn't. I am Jewish, so I don't have to wonder, âWhat would a Jew do?'”

In one hilarious scene in the film, Rabbi Belinski has just been beaten, robbed, and abandoned by bandits in the desert when he spots a happily familiar sight in the distance: men in long black coats and black hats. He rushes toward them, assuming they're Hasidim, frantically talking in Yiddish about his ordeal, when he realizes they're not fellow Jews: They're Amish. I ask him how he learned the Yiddish that he jabbered in the scene. “Oh that was from Mel,” he says with a laugh. “I told him, âI want to get all excited when the Amish come; what can I say when I'm trying to talk to them and I think that they're

Jews

and I want to tell them I was beaten upâ” Suddenly he's in character, accent and all. “âThey nearly killed me, they chopped me, they kicked my kishkes!' And I asked Mel, âHow would I say that in Yiddish?' And Mel said, âYou say,

G-gyhagen machin dyhuda

yhiddina

. . . !!'” (It's a rant of makeshift Yiddish that sounds like vintage Mel Brooks.) “I told Mel, âWait! Wait!' And I wrote it down. I got it all from Mel. Whether it makes any sense, I don't know.”

Before Harrison Ford took the cowboy role, it was offered to John Wayne. “Wayne wouldn't read it until we agreed to the usual price: one million dollars, ten percent of the gross,” Wilder says. “The studio stalled, haggled, finally said âOkay.' Wayne read it, he said, âI'll do it. It's a funny script.' He was in Long Beach. I said, âGive him anything he wantsâ billing, or whatever. If he does this movie, then it won't be perceived as a Jewish film; it will be a Western!' And then one of the guys from Warner Bros. went out to Long Beach and tried to

Jew him down

”âhe clearly uses the slur to make a pointâ“to $750,000, and Wayne quit. And so we lost John Wayne.”

I ask him if Harrison Ford ever mentioned being Jewish himself. “He probably said it.” Wilder seems foggy as to when, then remembers. “I think when we were in Greeley, Colorado. Harrison and I would go to dinner in a little pub that had a dartboard and we'd eat and then play darts afterwards. And at one point during some conversation, Harrison said, âWhy do you say that? I'm half-Jewish.' He certainly didn't seem Jewish.”