Southern Storm (46 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

The opposition failed to dampen forager ardor. “They loaded their wagons with anything they could find to eat for man or beast,” remembered a resident. “Corn and cured hams and bacon were their choice. They shot all the chickens and killed all the fat hogs and steers they could find, often cutting off the hams and leaving the rest for the buzzards to eat.” Prior to the arrival of the blue horde, area farmers had secreted their best animals and most critical supplies in the Mill Creek swamp, known as Old Bay. According to one local, for all their activity the Yankees never bothered to search through the thick swamp. One Bulloch County matron even boldly walked into the Federal camp, where she “bought used coffee grounds from them so as to have some real coffee again.”

Statesboro marked the end point for this day’s march by the two right divisions, while the left pair settled along the river across from Cameron, itself the night camp for the leading elements of the Seventeenth Corps. Some sixteen miles north and slightly west of Cameron, the forward units from the Twentieth Corps would call it a day after one of those grueling tramps, the kind that wouldn’t figure into the

pleasant memoirs that emerged decades later. The columns were passing through a region that was aptly described by an Ohio soldier as “swamp, swampy, swampier.” A new twist to the problems facing the wagon masters and their escorts was recognized by a New Jersey officer who “found roads or ground good for traveling except in some places where a wagon and mules would gradually sink down one or 2 feet with perfect ease and without any previous warning, breaking through the crust and necessitating some hard work and a little swearing to extricate the same.”

An infantryman with the train guard witnessed “teams at bad holes doubled up and pioneers to facilitate progress built bridges of pine corduroy.” Held to their task by the physical labor necessary to keep the wagons moving, one of the regiments guarding trains, missing out on all the goods being collected, had to content itself with a raid on the army’s hardtack reserve. “The crackers were being carried for us and were needed then, full as much as on any subsequent time and why should we go hungry in the presence of plenty?” a soldier rationalized. “At any rate we took the crackers.”

A major delay in the December 4 schedule occurred at a point where the road being used by the Twentieth Corps passed over a mill dam holding back Horse Creek. The earthen barrier had not been constructed with heavy military convoys in mind, so hardly had the first division completed its passage when the stressed dam gave way. According to a Wisconsin diarist, the breach “overflowed the road—so that we lost several teams.” An Illinois soldier on the scene soon observed that the watercourse was “swelling at so rapid a rate that it was impossible to cross on pontoons, and [we] had to remain there for about three hours.” “Every one wet and mad and disgusted with the general run of things,” griped a New Jerseyman.

The delays did allow time for some detachments to carry out the sad necessity of burying soldiers who had died during the march. Chaplain Lyman Ames was among those who took care of the sick and injured for the Second Division of the Twentieth Corps. Since leaving Atlanta, he had presided over the interment of nine Union soldiers, most for illness or accidentally inflicted wounds. In Sherman’s calculations, those unable to make the march because of sickness or injury were supposed to have been culled out before the movement began, but in reality, not everyone who was unwell chose to be separated from

his comrades. With treatment facilities barebones, the constant movement over dirt roads put added strain on those being conveyed in unsprung wagons.

It was a cruel dilemma. “We have not the transportation to spare to carry wounded men, and to leave them in the hands of the rebels would be worse than death itself,” explained a Wisconsin soldier. Before setting out this morning, Chaplain Ames gave final rites to a boy from the 29th Ohio who died of fever. During the long break waiting for the dam flood to subside, a second Ohio soldier passed away. “A large number present at the burial,” Ames noted. “Addressed them briefly.”

The two divisions of the Fourteenth Corps moving in sync with the Twentieth left Lumpkin’s Station this morning, but not before “burning the ties and bending the iron.” “No forage of any account,” grumbled an Ohioan. An Indiana officer termed it “a very poor country, sandy and marshy.” The fact that Union forces only controlled areas actually occupied was demonstrated this day when the Union column’s rear guard was challenged by a detachment of mounted Rebels as it began moving out. “Rebs make their appearance ½ mile from us,” wrote an Ohio diarist. “Some little firing between them and stragglers…. Lieut. Hubley left his sword, belt & pistol in field where we lay. Rebs were so close he could not get it.”

Waynesboro

One part of the “game” that Confederate Major General Joseph Wheeler deftly handled was psychological warfare. He understood that the enemy was anxiously aware of being deep in Rebel territory and very much on their own. Anything he could do to increase their discomfort level might lower their combat efficiency, thus improving his odds in battle. He had put theory into practice during Kilpatrick’s first Waynesboro raid by maintaining harassment of the Yankee column both day and night. In Wheeler’s reckoning, these efforts had paid dividends, leaving the enemy “too much demoralized to again meet our cavalry” without close support. With the Federals once more knocking on Waynesboro’s front door, the Confederate general was still trying to keep them off balance.

The Federal infantry was camped near Thomas Station, with Kil

patrick’s men posted a mile farther north. About midnight, Wheeler’s men manhandled one, maybe two, artillery pieces as close to the Union picket line as they dared and opened fire on the cavalry bivouacs, clearly delineated by their campfires. This provoked a rapid response from the pickets, causing the cannon to withdraw, but the damage had been done. Two members of the 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry were dead, and a lot of officers went without much sleep this night.

Heading that list was Brigadier General Absalom Baird, commanding the Fourteenth Corps division supporting Kilpatrick. Roused from his slumber by the shelling, Baird and his staff rode out to the infantry picket lines to investigate, guided by the stalwart Major James A. Connolly. Baird was nervous. After they had ridden in silence for a while, he became convinced that they had actually passed through their outpost ring and were in imminent danger of being captured. Connolly, who had personally placed the pickets, knew better. “After some parleying I convinced him I was right and we went ahead to our pickets. But as this fuss was all over, and we could see nothing, we returned, getting to bed again, in bad humor, about 2 this morning,” he said.

An Indiana soldier reported that “General Kilpatrick was at General

*

Hunter’s headquarters during the time of the bombardment and said he would give them something to do in the morning.” True to his word, just a couple of hours after Baird and his officers tossed about in a restless sleep, the bugle notes of “Officer’s Call” sounded throughout the cavalry camp. While the company commanders gathered, the enlisted men brewed their coffee and managed breakfast. Then the meeting broke up as the officers scattered back to their units. The troopers in Company L of the 9th Michigan Cavalry listened as Captain David P. Ingraham explained that Kilpatrick had warned them “to prepare for a fight; that he was going out to whip Wheeler.” Not long afterward the bugles were at it again. This time they were announcing “Boots and Saddles.”

The infantry became bemused spectators when Kilpatrick insisted on having his entire division assemble in formation, filling the open fields near the railroad station. While it may have boosted the morale of his riders, the watching foot soldiers were less impressed. “So many cavalry in line in an open plain make a beautiful sight,” Major James

Connolly admitted. “But it’s all show; there’s not much fight in them.” His opinion reflected that of his boss, Brigadier General Baird, who had advised the Fourteenth Corps commander that the cavalry would only act if the infantry was nearby “in order to accomplish what is necessary to be done.” The troopers began moving off toward Waynesboro a little before 8:00

A.M

.

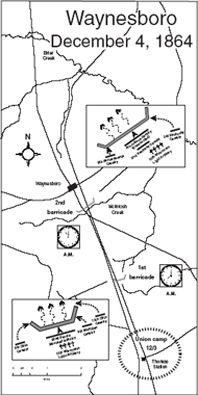

The 10th Ohio Cavalry had the advance. Hardly had its leading section passed through the Federal picket line before it struck a slight barricade manned by a regiment of dismounted Confederate cavalry. After a blast of gunfire sent the Ohioans packing, the rest of the regiment deployed, losing time in the process. A second advance found the barricade hastily abandoned, allowing the column to continue northward. About a mile farther the Federals encountered Wheeler’s main line of resistance, which a reporter present described as “a splendid defensive position with heavy rail barricade, with a swamp on one flank and the railway embankment on the other.” Wheeler afterward insisted that it was a single regiment holding the position, though another Southern source puts several regiments from Brigadier General William Wirt Allen’s division there. The enemy soldiers were ready and waiting, so there was no chance of overwhelming them by a quick rush. Kilpatrick ordered his Second Brigade (Colonel Smith D. Atkins commanding) to take the barricade.

Atkins’s plan was conventional but effective: pin down the enemy front with heavy fire while mounted columns turned the flanks. In this case the 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry (backed by the 10th Wisconsin Battery) was given the task of hammering the center, while the 9th Ohio Cavalry was to sweep around the enemy’s right, with the 9th Michigan Cavalry and the 10th Ohio Cavalry tackling the Rebel left. Even as his units were deploying, Kilpatrick rode out to his vidette perimeter to taunt Wheeler, a fellow West Pointer. A writer for the

New York Herald

, who doubtless polished the language for publication, recorded the tirade as: “Come on now, you cowardly scoundrel! Your [news] organs claim you have thrashed Kilpatrick every time. Here’s Kil himself. Come out, and I’ll not leave enough of you to thrash a corporal’s guard!”

The fight began in the center as the dismounted battle line of the 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry made contact. “We moved up through a slough and were well covered until we got within 200 yds of the

works when they opened with Artillery and musketry but shot too high,” reported an Illinoisan. The Yankee troopers levered their Spencers frantically to lay down a heavy suppressing fire, a process that an officer later described as “grinding out the shot from your coffee-mill guns.”

The 9th Ohio Cavalry swept around the enemy’s right flank. “I ordered my bugler to sound the charge,” recollected Colonel William D. Hamilton. “The companies began to move in an awkward irregular line, looking back for me…. Waving my hat, I called ‘come on, boys.’ A shout went up all along the line, and the glitter of their sabers following the fire of the carbines showed the mettle of the men, when the charge was on.” “Away we went on the gallop,” added another Ohio officer, “carbines firing, sabers flashing.” Trooper F. J. Wentz in Company H became an unwilling spectator when his horse, attempting to jump a small ravine, “landed lengthwise in the bottom of this excavation.” Wentz could only observe as his regiment “swept on close up to the edge of the swamp, driving everything before it.”

The attack of the 10th Ohio Cavalry came against the Rebel left. “At the word of command 200 bright blades leaped from their scabbards, and with a yell away we flew…like the sweeping cyclone, until the intervening space had been passed,” declared a trooper. “Moments seemed hours…. Suddenly a sheet of flame shot out from the…barricade…, and as suddenly horses and riders were in the last agonies of death, blocking the way.” “We could see an officer dashing down the [enemy’s] line with his saber raised and hear his voice, calling on his ‘brave men’ to ‘stand and fight the invaders,’” recorded a Buckeye. “This officer, we afterwards learned from the prisoners, was General Wheeler.” It was here that one of Kilpatrick’s favorites, Captain Samuel E. Norton, was seriously wounded. Just prior to the charge he had proclaimed: “Now for a name for our regiment.”

Wheeler riposted with his reserve regiments to stiffen the flanks. In response, the 9th Michigan Cavalry added its weight to the combat on the Union right. The Michigan men, said a report, “had to form while on the run from column of fours to that of battalions.” This was accomplished despite the fact that the “fog and smoke was now so dense as to almost totally obscure the enemy’s position.” Attempting to capture an enemy battle flag, the regiment’s adjutant, William C. Cook, “was knocked from his horse, and had his horse shot,” before being taken

prisoner. The Rebel color bearer had tried to spear the impetuous Yankee with his flagstaff, but it bent double instead. “I was glad I did not kill him for he was a handsome fellow,” remarked the Confederate.