Southern Storm (47 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

While this was unfolding, the men of the 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry rushed the barricade. The dismounted regiment overran it “and pumped their Spencers at the backs of the retreating Rebel soldiers.” In a brief melee along the barrier, the Illinois color bearer was killed, the flag he was carrying seized by an enemy officer. According to one account the dying color bearer shouted: “I’m shot. For God’s sake save the flag!” Before the Rebel could claim his trophy, one end of the flagstaff was grabbed by a Yankee trooper and the two engaged in a deadly tug-of-war, each masking the fire of comrades behind them. The impasse was only broken when the Illinois soldier fumbled out his revolver, compelling the Confederate (armed just with a sword) to surrender. Also killed in this action was George “Wait” Downs of Company I. “He never spoke after he was struck,” wrote a friend. “It will be sad news for his folks, but you know in battle, there is no distinction.”

Said Kilpatrick, Wheeler “made several counter-charges to save his dismounted men and check our rapid advance.” The Union general committed his ready reserve, the 5th Ohio Cavalry, yelling to its commander: “Col. Heath, take your regiment; charge by column of fours down that road and give those fellows a start.” The chronicle by the

New York Herald

reporter recounts that Kilpatrick went in with them. “They rode over the rebel barricade, hewed men down and used their pistols in a close engagement.”

It was during this part of the action that the leading files of Baird’s infantry reached the scene in time to be interested spectators. “The charge by our cavalry across the open field was a most sublimely grand, never-to-be-forgotten scene,” recorded an Ohio foot soldier; “no words of the writer can describe or paint the picture.” An Indiana infantryman present noted that some of the Rebels “had to retreat across a large swamp about a mile and the road was graded high and about wide enough for three or four men to ride abreast. They was in such a hurry they crowded each other off.”

Kilpatrick’s men now controlled the roadblock, but Wheeler wasn’t finished. A second, even stronger barricade had been erected just outside Waynesboro, along McIntosh Creek. Into this position the Confederate cavalry leader funneled his men (most from Brigadier General

William Y. C. Humes’s division), where they waited for round two. It wasn’t long in coming. Kilpatrick moved his First Brigade (Colonel Eli H. Murray commanding) into the fore, and it was these men who first espied the enemy’s position. “Between us and Waynesboro was a valley, through which ran a small creek,” remembered an Indiana trooper. “On the north or opposite side of this creek the rebels had taken their stand, having their artillery well posted.”

To his credit, Kilpatrick realized that he could not repeat the tactics that had served him so well at the first barricade. This time, Wheeler’s “flanks [were] so far extended that it was useless to attempt to turn them. I therefore determined to break his center.” Colonel Murray deployed his brigade, sending the 3rd Kentucky Cavalry against the Confederate left, the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry around to the other flank, and the 8th Indiana Cavalry (fighting dismounted) straight up the middle. Once more the 10th Wisconsin Battery was on hand for fire support, with the 2nd and 5th Kentucky Cavalry in reserve.

It took time to get all the units into position. Murray erred in setting up the 3rd Kentucky Cavalry first, halting it in full view of the enemy, where it became the object of their full attention. “No body of men ever stood fire any more resolutely; not a man faltered,” reported the regiment’s commander. “At length, the enemy’s fire becoming fierce and many of their comrades falling around them, they disregarded the restraints of discipline and rushed, with wild shouts, upon the enemy in their front.”

A dismounted Indiana trooper recalled that the 3rd Kentucky cavalrymen “moved rapidly upon the works of the enemy, without firing, and received such a shower of lead that they were thrown into confusion and hurled back upon the 8th Ind. Cav. which stood firm, and letting the Kentucky boys through, closed up their ranks and moved upon the works of the enemy, under heavy fire, which was returned from their Spencers…. At this time the 10th Wis. Battery was run into position and opened a fire of canister upon the enemy.”

Some of the resistance to this effort was directed toward the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry, which now struck the Rebel right. Just as in the case of the 3rd Kentucky Cavalry, the Pennsylvanians were goaded into action after being forced to wait under a galling fire. Suddenly, said one of the troopers, “our whole line commenced to move forward

without orders, at a slow walk of our horses at first, but faster and faster until we were charging at full speed.” The regiment’s commander, Colonel Thomas J. Jordan, was very much in his element. He found validation in the sound and fury of battle, writing afterward that during this engagements he “enjoyed the sweetest draught of pleasure that can enter a soldier’s heart.” In an open letter to the folks at home, a Lancaster County boy bragged that they “whipped” the Rebels “handsomely at Waynesboro.”

With both flanks engaged, the middle of Wheeler’s line became the dramatic focus. Under the cover of unrelenting volleys from the 8th Indiana Cavalry and artillery rounds sent over by the 10th Wisconsin Battery, the 2nd Kentucky rode forward, ripped passages through the barrier, and penetrated the enemy’s center. Wheeler’s second position collapsed as the various units disengaged to make their way through Waynesboro toward safety behind Brier Creek.

“Through the streets of Waynesboro we rushed,” crowed an Indiana rider, “through the streets of Waynesboro they retreated.” Wheeler himself admitted that his men “were so warmly pressed that it was with difficulty we succeeded in withdrawing.” Even as the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry pushed through the town, Colonel Murray abruptly detached half the regiment for a mission to the right, a fact the unit’s commander did not realize until he cleared the streets and drew his men into a line, only then realizing that he had just fifty or sixty troopers to take on all of Wheeler’s command. Fortunately, the Confederates were more intent on getting behind Brier Creek than beating up on a lone Union regiment, plus help was on hand in the form of Baird’s infantry. “Kilpatrick stopped; we marched thru his lines, formed in line, and went about a mile,” recollected a Missouri soldier. “We found neither works nor rebs and fell back and got dinner.”

In the town, Brigadier General Kilpatrick was relishing the moment. An Indiana man recalled him “rushing around like a child with a new toy, saying: ‘I knew I could lick Wheeler! I can do it again!’” “I seen one old Reb laying along the road (quite an old man) that had been [struck by] a saber stroke across his back and [he] was not dead yet but mortally wounded and under other circumstances his grey hairs would have appealed to my heart for sympathy,” said one of Baird’s infantrymen, “but we are not here to sympathize with men who brought it on

themselves.” Another foot soldier saw a “woman [who] was kneeling over the dead body of a Confederate cavalryman; perhaps it was her husband.”

North of Waynesboro, Wheeler’s men retreated across Brier Creek, closely shadowed by Kilpatrick’s two reserve regiments, the 5th Ohio Cavalry and the 5th Kentucky Cavalry. While the Kentuckians covered them, the Buckeyes destroyed the wagon and railroad bridges. Back in the town, some of the Pennsylvania troopers “amused themselves by examining the contents of the fine houses in town and making several bon fires of buildings, &c.” A seventeen-year-old female resident was drafted to entertain on her family’s piano, relocated into the street. “They made me play a long time,” she recalled, “but I never played anything but Southern airs. I must say I was not afraid of them, and I told them so, but they laughed it off.” Neither Baird nor Kilpatrick had any intention of sticking around very long, so by 3:00

P.M

. the Federals were hustling away to the southeast, toward a small place on the map named Alexander.

As the foot soldiers departed Waynesboro, an Indiana man marveled that the streets, empty right after the fight, were “alive with women and children who had on their Sunday clothes and it reminded me of home. They had hid in cellars while the fight was going on and come out to see us.” The next day a small group of these civilians would gather to bury a Georgia officer killed in the fighting. A young girl present remembered that “as there was no minister in the town, Judge Lawson read the funeral service and the ladies sang some hymns.”

Kilpatrick’s troopers formed the column’s rear guard. On top of today’s combat decisions, the cavalry commander faced a difficult personal matter. The promising officer Captain Samuel Norton, who was too badly wounded to be moved, would have to be left behind. A 10th Ohio cavalryman volunteered to remain with him. Kilpatrick’s contribution was a note to be given to Joseph Wheeler. “For the memory of old association,” Kilpatrick asked that Wheeler see that Norton received care and that the trooper be allowed to care for the officer he termed “very brave and a true gentleman.” In return for Wheeler’s courtesies, Kilpatrick promised “the thanks of your old friend.”

In their after-action reports, both Wheeler and Kilpatrick claimed to have been fighting against a numerically superior enemy, and each

was certain that they had inflicted grievous casualties on the other. Wheeler never bothered with a head count, but a cavalry veteran and later historian of his campaigns pegged his strength at about 2,000. Kilpatrick had left Atlanta on November 15 with some 5,000 riders; attrition and detachments had likely lowered the number engaged at Waynesboro to perhaps 3,700. So the advantage in numbers was with Kilpatrick, though the force multiplier enjoyed by defenders was in Wheeler’s favor.

The reckonings of the Confederate losses made by Union participants ranged from less than 100 to more than 500. A fair estimate of the killed, wounded, or captured would be around 250. Wheeler claimed inflicting 197 casualties on the Federals. A tally of the losses recorded in the various regimental accounts totals 79, suggesting that the Rebel fire, while enthusiastic, was not especially well aimed. Various regimental histories and contemporary newspaper accounts peg the total Union loss in this day’s action at between 125 and 190.

One target that Wheeler’s men did hit sported four legs. Saber charges against log barricades may have looked impressive from a distance, but close up they were hell on the horses. Kilpatrick reported “upwards of 200 in killed and wounded.” In a note to Major General Sherman, the cavalryman complained that his continuing duties as rear guard allowed the infantry to scour the country of livestock, leaving nothing for his troopers. “I…respectfully urge that a few hundred horses be turned over to me from one or more of the army corps marching on roads parallel or near to my line of march,” Kilpatrick requested.

Other than thinning the Yankee horse herd, what was accomplished? Some of Wheeler’s adherents stake the saving of Augusta on the outcome of the action, but it was never in either Baird’s or Kilpatrick’s brief to push beyond Brier Creek. Even had Wheeler offered no opposition, the destruction of the Brier Creek bridges would have completed the mission and turned the Union column to the south. Inflicting damage on the Yankee cavalry, while perhaps quenching a warrior’s thirst, left the core of Sherman’s striking force untouched; besides, with Baird’s infantry on hand Wheeler had no chance of delivering a telling blow.

One of the Federal infantrymen on the scene was certain that on this memorable day “the rebel cavalry have learned a lesson they will

not soon forget.” However, the only changes that would come to Wheeler’s operation had everything to do with topography and nothing to do with any learned lessons. Kilpatrick, anxious to feather his cap, could crow about thrashing his opposite number, though the close presence of strong infantry supports dims any luster of that accomplishment. A stretch of a branch railroad had been wrecked (mostly by the infantry), some bridges destroyed, and a few buildings trashed in Waynesboro. Not a victory of any substance, though both Bragg (in Augusta) and Sherman viewed it as necessary to shield their more important assets from enemy interference.

Perhaps most critical for Sherman’s grand movement, the tricky pivot toward Savannah was accomplished without any significant challenge to the lengthy tail that was his true weak point. A few mounted bands made some uncoordinated rushes at wagons that were easily repulsed by the train guards; at no point were the supply vehicles imperiled by anything other than the broken dams, sucking mud, or lousy trails.

None of which diminishes the fortitude and courage shown by the fighting men on both sides. Compared with infantry combat, cavalry actions were fast moving, briefly violent, and given to abrupt reverses of fortune. A momentary repulse or a charge generally meant little in the overall ebb and flow of the action, though it did spice up an official report. Still, at the point of sharpest contact the combat was as fierce as any of the more celebrated mounted engagements of the war. Yet in many ways the infantry officer Major James Connolly was not far off the mark when he observed: “A cavalry fight is just about as much fun as a fox hunt; but, of course, in the midst of the fun somebody is getting hurt all the time.”

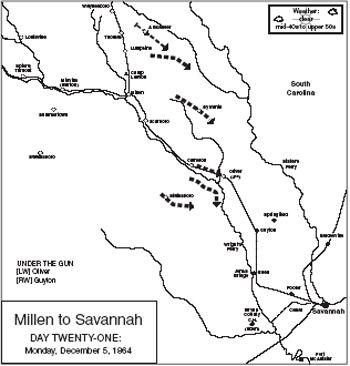

M

ONDAY

, D

ECEMBER

5, 1864

Left Wing

T

he immediate result of the combat at Waynesboro was a separation by both sides: Wheeler to regroup and resupply, Kilpatrick to screen the rear of Baird’s column marching through Alexander to Jacksonboro. “No trouble from the Rebels so far,” a relieved Ohio trooper commented about midday. His summary would hold true through nightfall. A Pennsylvanian observed that they were “entering the swampy country lying between the Savannah and Ogeechee rivers,” while an Illinois trooper saw the change in more immediate terms with the comment, “Good water…begins to be a scarce article as we find swamps instead of streams.”

An answer to Kilpatrick’s departing request on behalf of Captain Norton was making its way forward. Wheeler assured Kilpatrick that the suffering officer would “receive every attention which can be bestowed upon a wounded soldier.” A Waynesboro physician who had taken Norton into his house, Dr. Edmund Byrne, passed back to Wheeler that the Yankee “was doing well and [was] out of pain at last accounts.” Sadly, this brief rally preceded a dramatic decline, and before this day was out the valiant officer would be dead.

Coordinating Baird’s marching infantry column with Kilpatrick’s

screen kept Major James A. Connolly in regular contact with the cavalry officer. If anything, the infantryman’s low opinion of the mounted units in general and their leader in particular took on an even sharper edge. “Kilpatrick is the most vain, conceited, egotistical little popinjay I ever saw,” Connolly declared. “He has one redeeming quality—he rarely drinks spirituous liquors, and

never

to excess. He is a very ungraceful rider, looking more like a monkey than a man on horseback.”

Baird’s men were slowly closing the gap with the rest of the Fourteenth Corps, strung out along the main road between Waynesboro and Savannah. “Two or three plantations were all we passed, and they very poor ones,” wrote an Illinois diarist. “The whole surface of the earth is sand and the roads are almost ankle deep and marching diffi

cult.” “All our bed clothes and our dishes are full of sand,” complained a Minnesota soldier. Still, the column made steady progress until it reached the crossing of Beaverdam Creek, where the enemy had burned the wagon bridge and clogged the creek with brush. While pioneers cleared the obstructions, a detail from the 58th Indiana set to work rebuilding the bridge. The job wasn’t completed until nearly 10:00

P.M

., so the Fourteenth Corps settled down for the night around Jacksonboro, a small village that once had been the Screven County seat.

Black refugees continued to flock to the corps. “The number of negroes with us is perfectly astonishing and all have tales of the most barbarous cruelty at the hands of their master,” commented an Illinoisan. “They were a motley crowd, with clothes dirty and patched with many colors,” added an Indiana trooper, who continued, “Some of the women had young babies with them, and they were a nuisance in the army; but we could not drive them back, as they were seeking their freedom, and so they trudged on after us and we divided our rations with them.” “However they do not evoke my sympathy,” contributed an infantryman, echoing the sentiment of those commanding the corps. “I think them far better off with their masters than dragging along with the army.”

Matching general course and speed just a few miles to the south was the Twentieth Corps, which today passed through Sylvania, though it was a tough slog for many. “Streams or water swamps are so numerous that we can not learn their names any more,” grumbled an Illinois foot soldier. A Pennsylvania comrade recorded that “much of the road [was] being corduroyed through the interminable swamps.” “The wagons often get stuck in the mud, causing long and tedious marches…to come up with the advance,” contributed a New Yorker. “Some of the boys occupy their time during these waits playing chuckluck, draw and whiskey poker.”

Foragers reported mixed results; one termed the pickings “scarce,” while another inventoried a bounty that included “sweet potatoes, five pigs, hens, honey, bacon, etc., etc.” “Stop at house,” scrawled a diarist in the 129th Illinois. “Everything moveable taken, the women crying. Tell them they should have immigrated from this country before the war. They say that the women had nothing to do with the trouble. We can’t see it. Consider them our worst enemies.” Standing orders for

rearguard units were to destroy all bridges once the column had passed. For one Pennsylvania regiment, this meant burning a short span and breaching a mill dam to flood the roadway. Hardly had these soldiers begun their task when “three foraging teams came in sight on the other side of the road. The men were ordered to cross the burning bridge, which they did, and succeeded in backing the flames and brought their teams and horses across in safety,” reported the officer in charge.

A new problem arose that was identified by a surgeon in the 19th Michigan, who wrote: “Uncultivated land is covered with a sort of vine grass about a foot high & so plenty that the fire readily burns the country over giving us a fine smoke to march in.” Fresh orders directed officers to halt all unauthorized arsons, nothing that “such fires occasion great delay, especially to the ammunition train.” There were other related issues as well, though less readily apparent. “Seen far in advance at night, these fires often lead the weary soldiers to believe that they are approaching camp, and they press on with renewed vigor, only to be deceived, and to discover other fires still farther ahead,” said an Illinois man. “The dead pine trees often catch fire, and the creeping, writhing flames ascend from their base to the topmost branches. They may be seen miles away. These scenes are indelibly impressed upon the mind.” Reflecting on the daytime wagon jams and evening conflagrations, a New Jersey quartermaster quipped that his options were reduced to either being “Trampled by day…[or] liable to be burnt up at night.”

Right Wing

The biggest question hanging over the Seventeenth Corps this day was: How much of a fight was awaiting them at Ogeechee Creek? The answer, to everyone’s great relief, was not much of one at all. “After considerable maneuvering of troops and some skirmishing by the 35th New Jersey, the enemy retired and we crossed the creek and went into camp,” recorded an Ohio officer. According to a signal officer present, word of the enemy’s departure was brought by foragers who had filtered across the creek even as units were deploying to storm the position. This intelligence, he noted, “of course was pleasant to all but

those preparing for the attack.” The Rebels, chortled an Iowan, “concluded that they had better mover on, or they would get hurt, and the infantry left without firing a gun.” The railroad bridge had been burned, but the wagon crossing only de-planked, requiring a little labor by pioneer detachments before it was again carrying traffic.

Once over the creek, Seventeenth Corps soldiers not assigned to railroad wrecking went into bivouac to call it a day. Gunners from the 1st Minnesota Light Artillery enjoyed some poetic justice. “We got a number of the wooden spades they had used [to build their sand works] & burned them to cook our sweet potatoes by.” A member of the 10th Illinois recorded that four members of one company, who exceeded orders, were “tied by thumbs in front of [the] color-line for pillaging.” Others, under orders, took care of the railroad buildings as well as additional authorized targets. A Wisconsin man thought it a “splendid sight to see cotton gins burn.”

Sherman spent much of the morning on the porch of a two-story wood-frame house gazing over a well-tended garden while hoping for positive tidings from Ogeechee Creek. “Sat waiting for what might turn up,” noted Major Hitchcock. “General and staff on piazza talking,—General sometimes looking at map, and awaiting news from Blair.” The all-clear was sounded at 10:30

A.M

., allowing Sherman to proceed with his entourage. They reached Ogeechee Creek about a half hour later to find, as Major Hitchcock put it, “the birds had flown.” “This is better than having to fight those fellows in these bushes, ain’t it?” Sherman joked as they made their way across the rebuilt wagon bridge. Once on the other side, Hitchcock marveled at the now empty earthworks, which had been professionally sited to oppose any effort to ford the creek. A direct attack against a determined foe here would have been a slaughter. “Now you understand what a

flank movement

means,” a smiling Sherman told his aide.

As soon as his headquarters were established in the home of Mr. Matthew Lufburrow, Sherman drafted messages for major generals Howard and Slocum, canceling prior instructions to envelop the enemy position at Station No. 4½. He also wanted to tighten up the overall deployments. Now that they were approaching Savannah, whose garrison held the greatest number of enemy soldiers he had yet faced, Sherman was determined to keep his columns well in hand. The last thing he wanted was for any component to become so isolated from

the rest that a Rebel force, striking out from Savannah, might engage the Union soldiers with a force approaching numerical parity. If that meant halting one or two corps to allow the others to catch up, then so be it. In the note to Major General Howard explaining his thinking, Sherman emphasized that “we must move in concert, or else [all] will get lost.” Overall, however, the General was well satisfied with how affairs were progressing. Everything, he later wrote, “seemed to favor us. Never do I recall a more agreeable sensation than the sight of our camps by night, lit up by the fires of fragrant pine-knots.”

The one corps separated from Sherman by the Ogeechee River marched south and east in two columns of its own. While the Fourth Division of the Fifteenth Corps led the left half (nearest to the river) this day, its partner—the First Division—used as many “catch roads” as it could to keep abreast. By now experienced officers knew that railings needed to corduroy the lanes were hard to find in swampy areas, so when a fence was encountered, the soldiers were instructed to each shoulder a board, lugging it until needed. Foraging on this side of the river was generally good, with sweet potatoes and beef in ample supply.

“Negroes swarmed to us to-day,” declared an Illinois officer. “I saw one squad of 30 or 40 turned back.” Passing by a farm said to date to the Revolutionary War, another Illinois boy took notice of “a negro on the place who was over a hundred years old.” Other African-Americans were later remembered for their tragic experiences. This night an injured female slave reached the camp of the 103rd Illinois. She had helped other Union soldiers find the livestock hidden by her mistress, one Milly Drake. After the Yankees had departed, a member of the regiment reported that “gentle Milly took half a rail and like to wore the wench out. Broke her arm and bruised her shamefully. That was all the reason the girl had for running away.”

In one of the more remarkable personal journeys of the campaign, the officer on whom President Jefferson Davis pinned his greatest hopes of stopping the Yankee juggernaut was crossing Sherman’s wake to reach the front. General P. G. T. Beauregard had been in Montgomery, Alabama, on December 1, traveling toward Mobile, when he was handed

a dispatch from Richmond placing him in direct command of all coastal forces opposing Sherman’s march. Beauregard, acknowledging the new instructions on December 2, then plotted a bold course to reach the crucial area. A train carried him from Montgomery to Macon on December 3. From there the trail was by horse, departing Macon for Milledgeville, thence to Sparta and Mayfield, the latter about a day’s ride from Augusta. In his last message to Savannah before breaking contact, Beauregard had offered Lieutenant General Hardee advice on improving the city’s defenses besides urging him to use every effort to obstruct the roads. Further instructions would have to wait until he reached Augusta on December 6.

One of the irregular military assets available to Beauregard was touted today in a letter written in Louisville for publication in the

Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel.

The unit, not part of any formal order of battle, was called Hazzard’s Scouts. These soldiers, proclaimed the missive’s author, “have kept the enemy terribly annoyed on his rear and flank—dashing into them at unexpected places and capturing prisoners. The Hazzard Scouts are notorious for their gentlemanly deportment. They are never found away from their posts of duty or danger. Capt. Hazzard having been long engaged as a scout, seems to understand all the tricks of a Yankee and how to take advantage of them. He is certainly a terror to Yankees, knowing as he does how to handle his gallant scouts. There are few, if any, who surpass him as a commander of scouts. He is a gentleman and a soldier.”