Southern Storm (41 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

While it was more directly related to Sherman’s operation, the battle of Honey Hill paled in comparison with the grand-scale combat that also occurred this day in south-central Tennessee at Franklin. The quixotic General John B. Hood, ignoring Beauregard’s entreaties and adhering to a schedule of his own making, launched his much-anticipated invasion of the Volunteer State on November 21—the day before Sherman entered Georgia’s capital. Hood’s first goal was Nashville, after which anything seemed possible—at least to John B. Hood.

The same storm systems that brought discomfort to Sherman’s men in central Georgia struck Hood’s legions with even more misery. Snow, ice, and punishing cold pummeled the Rebel warriors. For the first ten days of this operation, Hood’s men shadowboxed with a small Federal army under Major General John M. Schofield that Major General George Thomas had positioned near the southern border to monitor enemy movements.

Hood, proving more determined and resourceful than Schofield, actually managed to get between the Union force and Nashville at a place called Spring Hill on November 29. The poor condition of Hood’s army, the matter of his personal exhaustion and professional shortcomings in command of so many troops, and a panic-inspired animation on Schofield’s part resulted in the Federals eluding the trap to take up a defensive position nearby at Franklin, with the Harpath River to their rear.

Furious at his missed chance at Spring Hill to deal the U.S. cause in Tennessee a serious blow, Hood ignored legitimate concerns and alternate strategies offered by his subordinates to hurl his army directly at the enemy’s defensive works at Franklin in a series of sledgehammer assaults that buckled and bent but did not break them. Of the approximately 22,000 Federals engaged, roughly 10 percent were killed, wounded, or missing/captured. In contrast, Hood’s army, numbering here some 23,000, suffered losses that exceeded one-third of its strength, including six irreplaceable generals.

Incredibly, Franklin was not the end of Hood’s campaign, merely an appalling midpoint. On December 1, Schofield would continue his withdrawal into the defenses of Nashville, where George Thomas

waited, still unsatisfied with the hand Sherman had dealt him and not at all confident he could stop Hood. For his part, Hood trailed after Schofield. Despite the awful damage done to his army at Franklin, given the stakes that were on the table and the absence of any alternatives, he really had no choice. Very soon now, Sherman’s cavalier allocation of troops to hold the line in middle Tennessee would be put to the ultimate test.

At this juncture, Sherman worried most that the enemy was going to mount a significant defense along the line of the Ogeechee River. He need not have concerned himself. Almost as if it had been designed this way, the zones where Sherman was expecting trouble fell outside those where Confederate leaders were focusing their attention. General Beauregard, in overall command, had departed Macon for Mobile, Alabama, where he believed his presence was urgently required. His

sole contribution to affairs near the coast was to advise Lieutenant General Hardee not to expect any more help in Savannah than he had already received.

Hardee’s attention was fully occupied by reports of an enemy raid against his rail connection to Charleston,

*

and the pressing need to build up his landside defenses. General Braxton Bragg in Augusta, temporarily tasked with directing operations against Sherman in Beauregard’s absence, limited his strategic initiatives this day to ordering repairs to the Georgia Railroad and urging Wheeler to keep hitting the enemy’s cavalry.

Whatever potential there was in a stout defense of the Ogeechee River line would be unrealized and unimagined by the men who, in Jefferson Davis’s way of thinking, should have been combining resources and coordinating efforts to stop Sherman. Instead, each had created a self-imposed arena of responsibility, beyond which no thought was given. It was as if none of the officers desired to impinge in the slightest on the prerogatives of the others. While courteous in the extreme, it was also not a very effective way of putting obstacles in Sherman’s path. As a member of the General’s staff observed about this time: “Every place we come to we fear that the rebels are fortifying such and such points always about two days march from us but we still continue our journey over a country having a greater natural capacity for protection than any I have yet seen.”

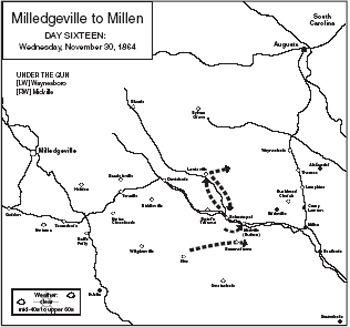

Combined Left/Right Wings

Two divisions of the Fourteenth Corps remained encamped around Louisville along with Kilpatrick’s bone-tired cavalrymen. The remaining infantry division followed its leading brigade southward toward the station on the Central of Georgia line known as No. 10, or Sebastopol. The security perimeter ringing Louisville was tested throughout the day by small bands of mounted men engaged in hit-and-run attacks. “There are not many rebels around us but they are slowly collecting in the hope of impeding our progress,” observed a Minnesota man.

Soldier Levi Ross was part of the 86th Illinois roused from its camp

reveries by a sudden uptick of firing on the picket line. The men were hustled into formation, then hurried toward the sound of the guns. “As we filed up the road we saw the enemy in line of battle and mounted for a charge,” remembered Ross. “Soon we reached the picket line, and deployed for the reception of the charge. Our entire regiment had come out and likewise deployed at short intervals on either side. The sight of reinforcements deterred the enemy from his intended charge yet he remained in line exposed to our fire. Occasionally he would dash down toward us, then suddenly wheel about and get out of range.”

This “game,” continuing throughout the day, was repeated at various points along the security boundary. Infantryman Ross had two close calls and a chilling reminder that the enemy was playing for keeps. He viewed four bodies of Union foragers, “all shot through the head and powder burnt. I saw them with my own eyes and therefore it needs no confirmation.” All this hostile activity grated on the nerves of the officer commanding the corps, Brevet Major General Jefferson C. Davis, who complained to his boss that his “foragers are circumscribed to the limits of the picket-lines; so the general commanding will see the necessity of our getting out of this soon.”

The division sent to Sebastopol managed to avoid all these problems as the enemy’s focus remained on Louisville. “Any quantity of forage on the road, in the way of potatoes, meat, sorghum, honey, &c.,” wrote a member of the 104th Illinois. Another in that regiment never forgot the celebration that greeted them when they reached the railroad station area. “The negroes had a grand jubilee after dark; the boys built a platform, provided a fiddle, and the darkies more than hoed it down, one old fellow dancing on his head, and keeping time to the music.”

Also congregating at Louisville was the Twentieth Corps. One division had already arrived; the other two finished wrecking the railroad as far as the Ogeechee River, where they destroyed the railroad bridge. The men then marched north to cross to the Louisville side below the city, using Cowart’s Bridge. To the west of the town engineers took up the pontoon bridge that had carried the wagons of the Left Wing across the Ogeechee.

Sherman made the decision to pause the Left Wing at Louisville entirely on military grounds. Yet it had an unintentioned humanitarian

impact, as slaves from the whole region began congregating there. “Thousands of colored people joined the columns every day,” recorded a New Yorker, “many of the women carrying children in their arms, while older boys and girls plodded by their side.” “Supposed to be 2,000 along with Army,” added an Illinois comrade. “Coming in very fast.”

For the Fifteenth Corps, this day’s marching kept the men entirely on the south side of the Ogeechee River, as Sherman intended. This was his ace in the hole should the enemy make a stand at Millen behind the natural obstacles created by the merging there of Buckhead Creek and the Ogeechee. If the Confederates did stand fast, the Fifteenth would be in position to cross the river below to flank them. For the men of the corps, that meant spreading across trails in Jefferson, Johnson, and Emanuel counties, pushing through a region of pine forests that gave way to swamps.

The “roads a complete wilderness,” complained a Missouri soldier, “only pine trees[,] the most stupid place God created.” According to an Ohio comrade, “during that whole distance [marched this day] only one log hut greeted our vision and that was inhabited by a ‘love lorn widder’ with six tow headed children.” A member of the 103rd Illinois encountered a German-American who professed complete loyalty to the Union. The sound of a passing band brought tears to his eyes and anger to his tone. “This is the first music I have heard in four years; it makes me think of home,” he blubbered. “D——n this Georgia pine woods.”

There were delays as numerous patches of swamp ground necessitated either a detour or corduroy path. “Have to make our roads,” groused a soldier in the 48th Indiana. “The sloughs are called creeks but they spread out like swamps,” complained an Ohio officer. “I do not think an army could move with any rapidity through this country during the wet season.” It all lent an air of exasperation to some of the men. “The roads are desperate,” scrawled one, “our supplies are becoming shorter and shorter, darkness seems to be falling on our path.”

Darkness fell across the path of the Sample plantation, seven miles below Summertown, where South Carolinian Sue Sample was visiting her sister-in-law. For days the ladies had been emotionally whipsawed by conflicting rumors—first that the Yankees could be expected any

day, then the reassurances that they were passing at least sixty miles away. The pair had just returned from visiting a neighbor when one of the plantation slaves cocked his ear and said, “Listen Miss Sue, what dat?” It was the sound of military drums beating, more like six miles than sixty distant. Sample went into the house to lie down, for she had hardly slept the previous night from anxieties. Hardly had she closed her eyes before she was shaken awake with someone saying, “Get up, the Yanks are in the yard.”

Sue Sample hurried downstairs to the sitting room. The sun had set, it was dark, but she could clearly make out that “a Yank was at each window with a cocked pistol in their hand, swearing all the time.” Large sweaty men pushed their way into the house, helping themselves to loose items and having a dinner prepared for them under protest. Recalled Sample: “I never was so frightened in all my life.”

The Fifteenth Corps finally settled in for the night around Summerville. Just to the north, the Seventeenth Corps was crossing the Ogeechee River at Station No. 9½, Burton. “The railroad bridge at this point had been burned but was easily repaired and quickly covered in a sufficiently safe and substantial manner to admit of the cavalry and infantry crossing, while a pontoon bridge was laid a few rods above over which the artillery and trains were expeditiously moved,” reported a staff officer.

Among those crossing with the Seventeenth Corps was Sherman and his headquarters. By the time the command group had reached the bridge, its approaches were a confused tangle of “wagons, footmen and horsemen,” which forced the party to pick its way “through slowly in single file, often having to stop,” recorded Major Hitchcock. Once settled on the other side, Sherman encountered one of the memorable characters of the campaign. Major Hitchcock identified him as “old Johnny Wells,” the former stationmaster here. Another staffer, Major George Nichols, thought him a “shrewd old fellow, with a comical build, he was evidently born to be fat and funny—as he was.”

Even though his story was a well-worn one—a quiet Union man opposed to the war—his winning ways had even Sherman enjoying his company. “Never met a man more quick, in his way, in shrewd and odd ‘points’ and laughable sayings,” noted Hitchcock. “There’s John Frank

lin went through here the other day, running from your army,” Wells declared. “I could have played dominoes on his coattails.” Accepting the pilfering and destruction that was going on even as they conversed, Wells said, “It’ll take the help of Divine Providence, a heap of rain, and a deal of elbow-grease to fix things up again.” According to Sherman’s military telegrapher, Wells “came into camp soon after tea and chatted with the General and staff until Eleven O’clock.”

Somehow Sherman did find time to attend to military matters. As late as 3:00

P.M

. he was still fretting over a possible enemy effort at Millen. When he provided movement directions to Left Wing commander Major General Henry W. Slocum, Sherman also advised him to keep an ear cocked toward Millen “in case you hear the sound of battle.” Some time later, a courier arrived from Major General Howard with the best possible news. One of Howard’s most trustworthy scouts, Captain William Duncan, had just reported in from a recon to the east. Duncan with his men had penetrated to “within three miles of Millen, on this side [south] of the river, and found no enemy.” Along the way, the Yankees fell in with a Rebel lieutenant whom they took prisoner. “Not much information could be got from him,” Howard related. Still, if Duncan’s report held up and the enemy wasn’t making a stand at Millen, then another important hurdle would have been cleared.