Southern Storm (37 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

All was quiet. The voltigeurs reached the river, where the major beheld an astonishing sight—Fenn’s Bridge was intact, “not a plank

disturbed, and not a rebel in sight.” With Connolly was Colonel George P. Este, commanding the division’s Third Brigade. The pair grinned at each other before putting spurs to their horses’ flanks to see who could race across first. In his account, Connolly diplomatically implies the result was a tie. The infantry humped after the officers to spread out along the east side, protecting the precious gift.

Connolly afterward encountered a local woman who identified herself as the toll collector. She told him that there had been Confederate cavalry here this very morning, but they had headed west to burn a span toward Sandersville, saying they would return later to wreck Fenn’s Bridge. The swift advance by the Fourteenth Corps’ men cut off the Rebels, allowing the Federals to gain control. “The Lord was ‘on our side’ this time, surely,” sighed a relieved Connolly. “For if that rebel brigade had burned the bridge this morning when they were here, we would have been compelled to build one before we could cross, and we could not have built one at all if there had been a regiment of rebels on the east bank to oppose us.”

Both flanking divisions utilized Fenn’s Bridge. An Indiana soldier remembered it as “an old wooden bridge none to[o] sound but all crossed safely.” Once over, the pair angled south toward Louisville on parallel roads, camping for the night in a defensive posture. There were smiles at Sherman’s headquarters when news of the successful crossing was confirmed. With the Ogeechee line now breached, all planning aimed toward the next potential trouble spot: Millen. As Major Hitchcock settled down at the end of a long day, his only thought was that “tomorrow the second Act of the Drama will be fully under way.”

Cavalry

For all his acumen as an operational planner and strategic visionary, Sherman had a blind spot when it came to handling cavalry. His entire army career never intersected with that branch of arms; consequently it was a weapon he did not know how to employ wisely. He failed to understand the combat strengths and limitations of cavalrymen, never grasped what they did effectively or what they did poorly, and had no practical appreciation of their special problems.

There was no integration of his cavalry division with his infantry corps. Scouting duties for the foot soldiers were handled, for the most part, by mounted infantry, engineers, detached cavalry companies, or staff officers; flank protection came from the swarms of foragers who effectively cocooned the line of march; while picketing duties were given to foot soldiers or mounted infantry. The jobs Sherman tended to give his troopers were railroad wrecking (which they did poorly), infrastructure demolition (also difficult without adequate tools), and attracting the attention of the enemy’s cavalry (which they did exceedingly well). Kilpatrick’s current mission parameters contained all three, though the one Sherman most emphasized was number four—freeing the prisoners at Camp Lawton.

After breaking contact with the Yankee infantry around Sandersville on November 26, Confederate Major General Wheeler pushed his riders north and west, toward Ogeechee Shoals. Shortly after midnight his men began scrapping with the two regiments Kilpatrick had posted to watch the back door.

Trooper Leroy S. Fallis in the 8th Indiana Cavalry (one of the two rearguard regiments; the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry was the other) recalled the Rebel strikes as “unexpected, and in the darkness things became somewhat mixed.” Hoping to realize maximum effect under the cover of night, the few Confederates involved made a substantial ruckus. Confusion reigned on both sides; at one point a section of the 8th Indiana Cavalry bluffed its way out of a tight spot by pretending to be a Rebel detachment; at another, a different Hoosier section was flanked out of its barricaded position and, in the words of a trooper, “fell back in some confusion.” Disruption rather than attack was the objective; once the Federals stabilized a situation, Wheeler’s men sought another weak point, allowing the Yanks to proclaim a successful defense while the Rebs enjoyed a successful harassment. According to Private Fallis, “we could hear the old rebel yell as they attempted some new move which was invariably met and repulsed.”

At dawn Brigadier General Kilpatrick continued his assigned mission toward Waynesboro and Millen. However, the information Wheeler had gathered convinced him that Kilpatrick’s real objective was to raid Augusta. “Being mindful of the great damage that could be done,” the Confederate general adopted a strategy of “pressing him

hard [so that] he might be turned from his purpose.” Here again the absence of any overall coordination squandered a valuable military asset. Wheeler made his own decision to concentrate on defending what was probably the best-prepared potential target along Sherman’s track—this at a time when more and more Confederate leaders on the scene recognized that Savannah was the most likely object of the enemy’s attentions.

Even more ironic was the fact that the enemy Wheeler was protecting Augusta against was clearly thinking of defensive, not offensive, measures, as his march arrangements made evident. Before breaking camp, Kilpatrick’s Second Brigade formed behind a barricade across the road, and at the word of command, the hard-pressed First passed through the Second. While the First took over the advance, the Second staved off Rebel dashes at the column’s rear. A member of the 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry described the process:

A company of fifty men would form at some point in the thick brush, with open fields in rear; in the road a squad of six or eight mounted men would halt, fire at the enemy at long range, then turn and retreat on the column; and on would come their confident pursuers at a gallop. When close up, the fifty concealed horsemen, cool and quiet from much similar practice, would volley them with their repeating rifles. Then the enemy would…deploy his skirmishers, and carefully feel his way…while the fifty mounted men were leisurely closing up on the column.

“Marched thirty miles and built 9 or ten barricades,” recorded an exhausted Ohio trooper. At one creek the Federals were able to destroy a bridge before the pursuing Confederates could reach it, forcing them to find an upstream ford, thus buying perhaps an hour of peace until the familiar sounds returned. “The rebels followed close…hooping and yelling terribly,” recollected an Illinois man. “It was evident that the Johnnies in our rear were becoming desperate and wrathy in the highest degree,” agreed a Pennsylvanian.

It wasn’t just the Rebels who were testy. Even before reaching Waynesboro, Kilpatrick’s men passed the Whitehead plantation, where the Yankee troopers helped themselves with the extreme discourtesy of soldiers pressed for time. When they departed, Catherine White

head declared them “certainly the vilest wretches that ever lived & must be overtaken in their wickedness, but if they are not punished in this world, God will certainly punish them in the world to come.”

For reasons unexplained, Wheeler today limited himself to a stern chase, allowing the head of Kilpatrick’s column to enter Waynesboro in the early afternoon, where some railroad equipment and associated buildings were set ablaze. It was about this time that the Federal general heard from Captain Estes that there were no Union prisoners to be liberated from Camp Lawton. In later reporting this revelation to Sherman, Kilpatrick tried to allay his chief’s anticipated disappointment. “It is needless to say that had this not been the case I should have rescued them,” he said; “the Confederate Government could not have prevented me.”

With his prisoner-liberation mission scratched, Kilpatrick led his men south from Waynesboro following the railroad. Roughly three miles outside the town he found a good location for a defensive camp; there he established a barricaded line with one flank anchored on the railroad and the other resting on a pond. Rather than allowing his weary troopers time off their feet, Kilpatrick kept every available man busy tearing up the tracks, so that he could claim some accomplishment of his assignment. It was not a decision welcomed by the officers, whose men were “sadly in need of rest and sleep.” They would not get much of either.

Behind Kilpatrick’s column, Major General Joseph Wheeler entered Waynesboro just after sunset. “The town was in flames,” he recounted, “but with the assistance of my staff and escort we succeeded in staying the flames and in extinguishing the fire in all but one dwelling, which was so far burned that it was impossible to save it.” Wheeler planned some nasty surprises for the Federals in the morning; meantime, he would continue to badger the rear guard, “to keep them in line of battle all night.”

While Wheeler continued to act as if the enemy were itching to turn toward Augusta, Kilpatrick’s intentions were in a different direction. With U.S prisoners gone from Camp Lawton, there was no longer any compelling reason to keep his command exposed to Wheeler’s assaults. Accordingly, as the Federal reported, “I deemed it prudent to retire to our infantry.” He intended his next day’s march to close on

Louisville, where he expected to reach the protective umbrella of Sherman’s main columns. That was, if Joe Wheeler would let him go.

M

ONDAY

, N

OVEMBER

28, 1864

The three cities directly under Sherman’s shadow reacted to the threat in different ways. The mood in Augusta was positively bullish. “The enemy’s position is becoming developed at last,” announced the

Augusta Register

. “Whatever may be his opinion of our strength, we are conscious that our force is not only able to protect stated points, but will be able to meet him in open combat, and make him rue the day he toyed with the iron spirit of the Southern people.” The paper’s editors also heaped praise on Lieutenant General William J. Hardee. “‘Old Reliable’ is too well informed of SHERMAN’S tactics to be outwitted by him,” they boasted. “He is one of the most vigilant and energetic officers in the service, and knows how and when to operate.”

In contrast to Hardee’s studied equanimity, Major General Samuel Jones, the officer commanding in Charleston, was in a near panic. Once more today he fired off a telegram to Richmond reiterating his imperative want of reinforcements. “I cannot too strongly urge my need of them,” he pleaded. This prompted a stern and immediate rebuke from the Confederate secretary of war. “It is impossible to afford re-enforcement,” James Seddon answered in no uncertain terms. “You must rely on your own resources.”

Self-reliance marked the tone of a proclamation issued under this date by the mayor of Savannah, Richard D. Arnold. “The time has come when every male who can shoulder a musket can make himself useful in defending our hearths and homes,” it read. “Our city is well fortified, and the old can fight in the trenches as well as the young, and a determined and brave force can, behind intrenchments, successfully repel the assaults of treble their number.”

Combined Left/Right Wings

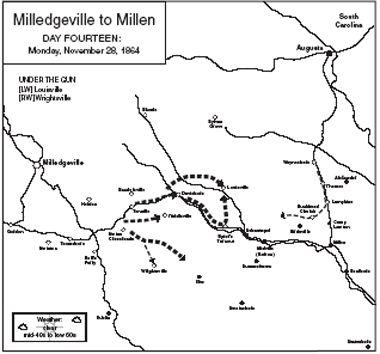

Sherman’s headquarters moved fifteen miles today, departing Tennille on a rambling course that jogged southeast for two or three miles, then picked up the old Savannah Road heading northeast, before turning southeast again to camp in the field roughly three miles outside Davisboro, not far from New Hope Church. The General was still gingerly coming upon the Ogeechee River with the Fourteenth and Twentieth Corps closing on Louisville, even as the Fifteenth and Seventeenth Corps marched in parallel a few miles to the south. “Thus we approached [the] Ogeechee [River] at two points,” wrote Major Hitchcock, now a more confident strategist, “one column at Louisville, which is ten to twelve miles above [the] railroad Bridge,—and [the] other…coming towards [the] railroad Bridge across the Ogeechee which is at Station 10.”

*

The command party traveled “on sandy roads, and through woods chiefly pine, though as yet we still see oaks and other trees,” continued Hitchcock in his travelogue mode. “Good farms along the traveled roads, and crops have all been good.” They crossed paths with Major

General Frank Blair, commanding the Seventeenth Corps, who showed them some captured correspondence from soldiers in Hood’s army representing a low state of morale and generally poor conditions. If Sherman gave any thought to what was happening to George Thomas in Tennessee, he gave no indication.

The officers lunched at a farm owned and occupied by one J. C. Moye, who received a guard detail to protect his residence; everything else on the place that could feed man or beast was appropriated. This night Sherman enjoyed a conversation with General Blair and two of his principal subordinates. An ever more admiring Hitchcock found the General to be “one of the most entertaining men I ever heard talk—varied, quick, original, shrewd, full of anecdote, experience and general information.”