Southern Storm (17 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

Almost from the start of the march, escaping slaves had been attracted by the passing Union columns. Today marked the first day that their presence in large numbers was becoming apparent. “The niggers flock around us and want to go with us,” a New York soldier observed. Sometimes the first encounter was a one-on-one. After getting directions from a slave, a Wisconsin regiment marched only a short distance when the black caught up with it. “Massa,” he said, “I’se

gwine ’long with uns.” His expression made it clear that the topic was not open for discussion. A Connecticut man came face-to-face with one of the dirty little secrets of the slave system. While his regiment was halted near a plantation, the soldier “got into conversation with a very pretty girl, thinking she was the daughter of a planter, from the fact she seemed so well educated. I made some inquiries about her parents when to my great surprise she told me that she was a ‘nigger,’ and both the slave and the daughter of the planter who was a minister.”

At Conyers, some of Sherman’s staff, including Major Hitchcock, spent time with a local Mrs. Scott, a widow. She readily admitted to telling her slaves that the Yankees in Atlanta had “shot, burned and drowned negroes, old and young, drove men into houses and burned them, etc.,” reported Hitchcock.

An officer prowled around outside, finding several reasons to worry. He observed that the railroad track here had been recently refurbished, disputing Hitchcock’s smug image of a hapless Confederacy. Also, he noticed that they were entering a region with more sand in the soil and patches of white clay, “which makes the worst mud.” All would be fine as long as the rains held off. On the plus side, found copies of Augusta newspapers (dated November 13) were encouragingly silent regarding the prospect of an enemy invasion.

When Sherman’s headquarters were set up for the night, about a mile from the Yellow River, the General sent for a local man to advise him on the roads and river crossings. “Don’t want white man,” he snapped. One of his aides, Major James McCoy, finally fetched a slave. Major Hitchcock, who thought the black man was a “very intelligent old fellow,” recorded Sherman’s attitude as “polite.” Once the General had learned all he could about local conditions, the conversation turned to other matters. He told the patriarch that he was “free if you choose and deserve it. Go when you like,—we don’t force any to be soldiers—pay wages, and will pay if you

choose to come

: but as

you

have family, better stay now and have general concert and leave hereafter.” According to Major Hitchcock, Sherman was especially adamant on one point. “

But don’t hurt your masters or their families,

” he said with emphasis, “

we don’t want that.

”

Sherman’s command style during the first phase of the great march remained very much hands-off. Courier contact between the wing

commanders and his headquarters was minimal, nor were signal officers tasked with maintaining more than intermittent communication between the separated columns. Sherman was counting on an initial period of confusion on the Confederate side regarding his route and objectives. He was also banking on the unimaginative steadiness of Howard and Slocum to stick to the plan.

During the “selling” of the march to Grant, Lincoln, and even Thomas, Sherman had suggested that Hood might well abandon his Tennessee schemes to chase after him. Such a possibility was never part of the daily force assignments. Everything in the disposition of Sherman’s forces on the march was forward looking; there were no backward glances. This evening, Sherman’s Left Wing commander took advantage of the short distance between the Twentieth and Fourteenth corps to send his boss a brief progress report. After explaining the moves he intended to make in the next few days, Major General Slocum concluded with words that must have brought a smile to Sherman’s weathered face: “I have seen no enemy and everything is working well.”

For many of those in the Fourteenth Corps, today was the first day of serious railroad wrecking. “We pry some of the rails loose then all get on one side of the track & turn the track entirely over,” related an Ohio diarist. “When the end first started goes over the men run behind and past those who are lifting so it is kept moving like a furrow unless it breaks apart. If it does then we have to look out or we get hurt.” “The ties were all burned and the rails bent,” added an Illinois man. A Minnesota soldier recalled tearing and burning the line until “we arrived at the smoking embers of the work of troops in advance of us.”

Along the destroyed tracks at Conyers, a squad from the 34th Illinois prowled the village, having been told that the provost guards had pulled out and that there still was plenty of food for the taking. After helping themselves, the men hauled their load to camp. “I shut my eyes not with a clear conscience,” admitted one of them, “but with the clear satisfaction that an excellent breakfast would be mine in the morning.”

Even as the two prongs of the Left Wing were settling into night camps, other actions were unfolding to ensure the next day’s progress. The 9th Illinois Mounted Infantry, under its commander Lieutenant Colonel Samuel T. Hughes, normally employed screening the advance

of the Twentieth Corps, “dashed into Social Circle before dark,” reported a newsman present, “and nearly succeeded in capturing a train of cars. Failing in this, [Hughes]…contented himself with burning the depot and coming back to camp with a rebel surgeon and $2,700 in rebel money.”

Back in the camps, the soldiers in the Second Brigade, Third Division, Fourteenth Corps were trying to sort out a strange incident. It began about midday, when the brigade stopped for dinner about four miles beyond Lithonia. Some members of the 101st Indiana caught a man in Union uniform skulking around the bivouac. According to a Minnesota soldier, the suspect (whom just about everyone thought was a spy) “attempted to sham insanity, but did not succeed in deceiving anyone but was marched under guard to brigade headquarters.” Added an Ohioan: “He is dressed in our uniform and pretends to be insane.” The prisoner traveled with the division to Conyers, where the Second Brigade bivouacked for the night. Another Ohio boy related that the suspect “tried to get away after dark, the guard shot at him & run his bayonet through him, but after it all he was so fast he would have gotten away had not Cap. [William Wallace] overhauled him & knocked him down with his saber reversed.” The man’s wounds were serious, but he appears to have survived the incident. With fine understatement, another Ohio man noted: “He still tells a confused story.”

*

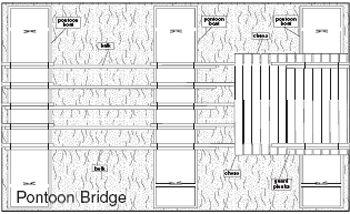

More routine matters were under way at the point where the Fourteenth Corps expected to cross the Yellow River, just below a railroad bridge that had been destroyed in an earlier raid. While nearby infantry prepared dinner or flopped down for the night, members of the 58th Indiana toiled on their first pontoon assignment of the campaign. Illumination was provided by torches and bonfires. The river here was some 100–120 feet wide, and the plan was for the army to cross in the morning on two bridges. While pioneer troops struggled against steep banks to construct an approach to the river, the Indiana engineers brought up their wagons to unload the flat-ended pontoon boats. The craft (sturdy wood frames with reattachable canvas sides) were pushed out onto the river, then anchored stepwise from bank to bank, some six feet apart. Each of the two crossings required six boats, each end being firmly lashed to the river bank. Next a series of long beams or

balks were laid across the boats, reaching from shore to shore. Perpendicular atop these came the planks or chesses, held in place with guard planks. Having trained long and hard for just such a circumstance, the Indiana engineers had the bridge ready for traffic well before dawn.

Left Wing orders written tonight addressed the slow movement of the wagons and the wasting of ammunition. “Brigade commanders should give their personal attention to the movement of the trains in their charge,” admonished Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams of the Twentieth Corps. A Fourteenth Corps directive made it clear that the “use of cartridges in killing of sheep, hogs, cattle, &c., foraged in the country is positively forbidden.” Those with the authority to order buildings burned were cautioned to be mindful of the surrounding foliage and to take steps to ensure that the fires did not spread into nearby woods, where the flames could easily spread out of control.

F

RIDAY

, N

OVEMBER

18, 1864

Midnight–Noon

Right Wing

M

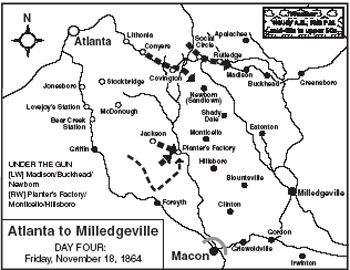

ajor General Oliver Otis Howard was not by nature a high-strung individual. Nor was he an especially cerebral officer; however, he now faced a situation that demanded the probing thoughtfulness of a chess master. Part of his mission was to execute a believable threat against Macon, and toward that end his line of advance was taking him closer and closer to the Rebel citadel. This proximity posed a danger that Confederate authorities could not ignore, but at the same time it put Howard’s Right Wing in significant peril. For the next few days his strung-out columns would be vulnerable to hit-and-run attacks launched from the armed city, and the limited road network had brought his two corps together at a water crossing without any existing bridge. It would take time for his military engineers to build one, and until they did, the bulk of his command would be stalled on the Ocmulgee River’s west bank.

The first order of today’s business was to protect the ferry area. A thin line of pickets from the 29th Missouri had staked Howard’s claim throughout the night; now he had to up the ante to solidify his control. The call went out to the division nearest Planter’s Factory, which

proved to be the Third of the Fifteenth Corps. The Federals had already secured the river craft that plied their trade here, but even with these in hand it was slow going. A member of the 93rd Illinois, the second regiment to make the passage, described his transportation as “an old fe[r]ry boat” and calculated “only 50 could get on at a time.” A comrade in the 63rd Illinois put the volume at “about 30 men” in each circuit made by the “small Ferry boat.” “As the enemy was known to be near,” added an infantryman in the 4th Minnesota, once across “a detail threw up some light breastworks.”

Through an oversight, the pontoon detail had not been staged forward at the end of yesterday’s march, so valuable time was lost while the engineers and their wagons squeezed through the congestion to the riverbank. It was not until nearly 11:00

A.M

. that the first pontoniers arrived, a section of thirty wagons pulled by as many mule teams, enough material to construct one floating bridge. The order was for two, but the other pontoon section was nowhere in sight. Those on hand from the 1st Missouri Engineers set to work, their efforts spurred on by the lowering clouds threatening a storm.

With the various columns halted for an indeterminate period,

foragers had time to prowl. “We lived on the fat of the land today,” recorded an Ohio diarist. “The Reg’t had more Fresh Pork[,] Sweet Potatoes &c than they could possibly use.” The sentiment was echoed by a brigade commander in the Seventeenth Corps who recorded an “abundance of sweet potatoes and fresh meat, and some meal, flour, sugar and salt besides forage for animals, and some horses and mules. We live well.”

The delay also allowed the word of the Yankee presence to spread among the surrounding plantations and farms. “About a hundred Negroes came in,” observed an Ohioan, “each bringing a good horse or mule.” A squad from the 10th Iowa was helping itself to well water in front of a house, watched over by a black servant who gradually came to realize what was happening. According to a soldier present, “he took a frantic spill & screamed out in a most frightful strain (as he pointed off to the East): ‘Our folks! Our folks! Gone! Gone! Gone!!!’” As the 63rd Illinois marched past a slave sporting a black silk hat and standing alongside three women, a soldier in the ranks called out a friendly invitation for him to come along. The black man nodded, shook hands with the women, said, “I’re off,” and eased into the blue ranks. The women, recalled a Illinoisan, “all put their big aprons to their face and began to cry. It was a sad parting scene, and to us a reminder of the tender chord that was touched when we said ‘good bye.’”

Planter’s Factory was a major object of interest for the soldiers in the area. The cloth manufacturing facility had been located where the river level dropped precipitously to provide an ample supply of water power. “There was a grist mill and a saw mill besides the factory which was four stories high, new, and in fine running order,” recollected an Illinois soldier. A cannoneer noted the complex as consisting of “2 splendid buildings which the Rebels had used night & day for the manufacture of cloth for the army.” An Indiana man eyed “lots of women & girls” in the workforce, estimated to number 150. A staff officer with General Howard, who counted seventy-five looms, spoke with the owner, who claimed he had only purchased the place a month ago. In other circumstances the view at the plant could be described as picturesque. Wrote a member of the 20th Illinois: “The most majestic scenery was seen at the mills[,] Steep high banks, rocky bottoms and deep cascades.” Artistically attractive it may have been, but there was

also no doubt that Planter’s Factory was a legitimate target slated for destruction.

Brigadier General H. Judson Kilpatrick had his cavalrymen in the saddle soon after sunrise to execute his feint against Forsyth. Throughout the morning his troopers tramped slowly along the back roads heading south, flushing out several Rebel vidette posts as they went, almost always letting the enemy scouts escape to Forsyth with word that the Yankees were coming. By the time his advance had pushed within five or six miles of the rail station and supply depot, Kilpatrick was “convinced that the impression had been made upon the enemy that our forces were moving directly on that point.” His column now swung east, then angled northward to New Market, where the troopers rested.

The feint proved everything Major General Howard had hoped for when he ordered it. Confederate field commanders remained convinced that Forsyth had been a prospective target, and only their determination to hold it prevented Sherman’s riders from adding it to the list of violated towns. Besides the militia manning Forsyth’s defensive positions, zealous partisans burned all the “bridges on the road from Forsyth to Indian Springs.” Both generals Wheeler and Gustavus W. Smith took credit for the victory. “On the 18th, after a series of severe, but successful, engagements with Kilpatrick’s Cavalry, we turned him off from his march upon Forsyth, saving that place also,” read one report of Wheeler’s actions. For his part, Smith crowed that his civilian-soldiers “reached Forsythe…just in time to repel the advance of Sherman’s cavalry and save the large depot of supplies at that place.”

Left Wing

The Twentieth Corps marched Second Division first today; so, “long before chicks began to squeal for life,” Brigadier General John W. Geary had his soldiers moving. Behind them came the Third Division, which stopped in Social Circle long enough for the men to grab an early lunch. “Some of the 85th boys are cooking dinner,” said an Indiana soldier; “others are engaged in tearing up the railroad track; some

feeding their horses and mules from a corn crib near by, while others made a raid on a barrel of sorghum, went after pigs, chickens, etc.” Soldiers entered the house of the George Garrett family, where they helped themselves to the larder besides giving two little girls a good fright. Before they left, one of the Yankees took the stopper from a barrel of syrup stored in the cellar, letting it gurgle onto the dirt floor. “I thought this a dirty, mean trick,” recollected one of the youngsters.

“Citizens don’t like the ‘Yanks,’” observed an Illinois man. “One Rebel woman wishes South Carolina would sink for bringing on this war. Thinks we ought not to trouble Georgia because it was last to secede. We can’t see it.” A New Yorker thought Social Circle was a tidy-looking place with a fair number of “good looking girls.” The ladies kept their distance, however, prompting another New York infantryman to claim that the place was misnamed, with “no evidence of the residents being either social or cordial with us.” The receptive mood wasn’t improved when the railroad depot and a nearby cotton warehouse were set ablaze. However, most of the town’s striking residences were spared the torch.

Outside Conyers, where the encampment of the Third Division, Fourteenth Corps, was bustling (the men marched second today, preceded by the Second and followed by the First), Major James A. Connolly hustled to complete some unfinished business. When he arrived here yesterday, Connolly (on Brigadier General Absalom Baird’s staff) had learned from slaves of a nearby plantation owner named Mr. Zachry, whose son, in the Confederate service, had sent his father a captured U.S. flag. Under Connolly’s orders the plantation house was searched and its owner questioned, but no flag was found. Today Connolly was determined to settle the matter.

He threatened the elder, telling him that the Yankee boys knew about the hidden standard, and unless he produced it his house would be burned once the army marched away. When Zachry begged for a guard, Connolly refused, repeating his prediction that the minute the officers departed, vengeance-seeking soldiers would torch his place. Connolly could be very convincing. “In less than ten minutes the old rascal brought the flag out and delivered it up,” the officer said with grim satisfaction, adding, “I don’t know whether his house was burned or not.”

For his part, Sherman was matching wills with the weather. Hitchcock described the morning as “cloudy and threatening rain,” while Sherman believed it to be “the perfection of campaigning, such weather and such roads as this.” On their way to the Yellow River, the headquarters party paused at the Reverend Gray’s house, then occupied by the good minister’s wife, her daughter, and grandchildren. While Hitchcock chatted, soldiers ran free around the property, helping themselves to all kinds of forage. “Evidently bitter rebel, but civil enough, and talked quietly,” recorded Hitchcock. “Never saw Yankee soldiers before ‘except prisoners passing.’ Like a woman, that!”

Sherman and company, reaching the pontoons built overnight by the 58th Indiana, traversed the Yellow River without incident. The water at this point was about one hundred feet wide, and it ran deep, though Major Hitchcock thought it “fordable.” As they were passing over, cattle were being herded across the river in two groups, one wading near the ruined railroad bridge, the other forced to swim downstream from the pontoons. “Cattle are the most trying things for pontoon bridges,” Hitchcock commented, “apt to crowd and rush.”

As the headquarters party drew close to Covington, word came that a deputation of local notables was waiting to greet Sherman. The General, recalled another aide, “not anxious to witness such an instance of submission, prudently avoided them by taking a back street through the town.” Hardly had they turned onto the detour when a young man in Confederate uniform intercepted them. The enemy soldier, wounded in Virginia and recuperating in Covington, had been told by the provost guards to surrender to Sherman. The General promptly turned the invalid over to Colonel Charles Ewing of his staff, who wrote out a parole for the young man after learning that “there is a mighty pretty girl where he stays.” Winks and nods were shared as the grateful Rebel headed back into town.

A couple of young and adventurous signal corps officers with Sherman’s party, learning of his flanking maneuver against the reception party, decided that a prepared meal shouldn’t be missed. Appointing each other the General’s representatives, they presented themselves to the welcoming committee and were royally wined and dined. “This was all intended for Genl. Sherman,” mused an aide, “but as he had declined to partake they did the best they could.”

Noon–Midnight

General Beauregard’s efforts to energize Confederate defenses against Sherman were set back today thanks to the worn-out transportation network. His preferred choice to take command, Lieutenant General Richard Taylor, was stuck on the road from Mobile to Macon, and exactly when he would arrive was anyone’s guess. With Taylor checked, Beauregard went to the next name on his list by recommending to Richmond that Lieutenant General Hardee, then in Savannah, be given temporary authority over Macon.

Beauregard was himself stalled in transit, having only just reached Corinth, Mississippi. Since he could not be present in person at this critical time, Beauregard tried to project his presence through a ringing proclamation.

TO THE PEOPLE OF GEORGIA:

Arise for the defense of your native soil! Rally round your patriotic Governor and gallant soldiers! Obstruct and destroy all roads in Sherman’s front, flank, and rear, and his army will soon starve in your midst! Be confident and resolute! Trust in an overruling Providence, and success will crown your efforts. I hasten to join you in defense of your homes and firesides.