Southern Storm (19 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

One fair face that did not disappear belonged to Tillie Travis, who sat quietly knitting as the solid masses of Union soldiery trooped past her porch while groups rummaged around for food. Her stoicism was

a pose, for Tillie was not known for holding her tongue when it came to the subject of the Confederacy and her worried mother had put the fear of God into the girl to keep her silent. Tillie held her vow until a Union officer “attempted to reconstruct me by arguments to prove the sin of Secession.” Tillie’s swift response at last drove the Federal away, but not before he commented, “I see it is no use to argue with you.” Tillie had a secret laugh on the plucky Yankee, for snug in the center of the yarn balls she was handling were gold watches, hidden in plain sight for safekeeping.

Experiences of Covington’s blacks covered a broad spectrum. “Negroes all want to follow us[,] but our limited supplies prevents our taking many,” wrote a diarist in the 34th Illinois. A comrade in the 105th Ohio related that he “saw several darkey women and men who wished to come. I advised the women not to come, they were anxious to come and said that they were abused by their masters shamefully.” Slaves who crowded up to the ranks of the 21st Wisconsin seemed genuinely surprised that the fearsome Yankees did not sport any horns. “Some of the boys told them that, in order not to scare them we had taken them off and put them in the wagons,” quipped a member of the regiment.

Another side to the story was vouched for by Tillie Travis, one of whose young female slaves came running up to the house shrieking that she was being robbed by Sherman’s men. A nearby Federal wondered aloud what all the fuss was about. “Your soldiers,” Tillie replied, “are carrying off everything she owns, and yet you pretend to be fighting for the negro.” When the slave girl saw an officer’s black servant wearing one of her hats, she went up to him to shake her fist in his face. “Oh!” she exclaimed, “if I had the power like I’ve got the will, I’d tear you to pieces.”

Passing quickly through Covington was a section of the 58th Indiana, hurrying its pontoon train to the Alcovy River. The first elements of the Fourteenth Corps to reach there found an improvised but usable crossing via a platform built on the ruins of an original bridge. It was good enough for infantry, but wouldn’t take wagons, so orders went back to the Yellow River for one of the sections to hustle forward. The new instructions arrived at 4:00

P.M

. Thirty minutes later one of the two pontoons had been dismantled and packed for travel. Less than two hours after that the Indiana engineers were setting to work at the

Alcovy River, which one of them described as “a deep, sluggish stream, with almost no banks,” about seventy-five feet wide. The officer in charge decided to run his bridge alongside the platform already in place, so within two hours the new pontoon was handling traffic. Sherman’s secret weapon was performing to expectations.

The General’s night headquarters were located about a mile and half west of the Alcovy River on the farm of Judge Harris. After asking around, the

New York Herald

reporter learned that the jurist, who hailed from Massachusetts, was not a kind master. Estimates of his slaveholdings ranged from 60 to 200, housed in what the correspondent called a “village of negro huts.” A crowd of curious and excited blacks was on hand as Sherman’s staff began erecting the night camp. “Glory be to de Lord, de Lincoln’s hab come!” called one, while another shouted “Bress de Lord!” Major Hitchcock asked a younger member of the group (he thought him twenty-five to thirty) why he had left his owner. “I was bound to come, Sah,” he answered, “good trade or bad trade, I’se bound to risk it.” Hitchcock thought that the simple faith these men and women had in the Union presence was striking and touching.

Sherman had another black elder brought to him to be queried about local roads and conditions. As Sherman recollected the moment, he asked the slave if he understood what the war meant for him and his people. The patriarch “supposed that slavery was the cause, and that our success was to be his freedom.” Believing that authority in the slave community was vested with the elders, Sherman patiently explained “that we wanted the slaves to remain where they were and not to load us down with useless mouths…, that our success was their assured freedom; but that, if they followed us in swarms…it would simply load us down and cripple us in our great task.”

To the end of his life, Sherman was convinced that the “old man spread this message to the slaves, which was carried from mouth to mouth, to the very end of our journey, and that it in part saved us from the great danger we incurred of swelling our numbers so that famine would have attended our progress.”

It was also at this place that Sherman saw firsthand how some of his orders were being implemented by the common soldiers. He encountered one “with a ham on his musket, a jug of sorghum-molasses under his arm, and a big piece of honey in his hand, from which he was

eating.” Catching the stern look of his commanding officer, the quick-thinking Yankee stage-whispered to a comrade: “Forage liberally on the country.” Sherman said he “reproved the man, explained that foraging must be limited to the regular parties properly detailed, and that all provisions thus obtained must be delivered to the regular commissaries, to be fairly distributed to the men who kept their ranks.”

Earlier in this evening, Sherman had another run-in, this witnessed by the colonel of a regiment who related it to the

New York Herald

reporter. Said the officer, “a number of soldiers…were filling their canteens from a molasses barrel, near Sherman’s headquarters, [and] were quarreling over the division of the syrup, when Sherman passing by cooly crowded in among them, and dipping his finger in it put it to his lips, remarking, ‘Don’t crowd, boys, there is enough for all.’”

A sack of Rebel mail intercepted in Covington was left at Sherman’s camp for Major Hitchcock to peruse. Among the missives he discovered the letter that Miss Zora M. Fair had composed in Oxford for Governor Brown, recounting her adventures as a spy in Atlanta. From others in the sack Hitchcock gathered that Miss Fair’s friends did not approve of her extracurricular activities. He brought the note to Sherman’s attention and was surprised when the general ordered a detail to knock on doors in Oxford to try to find the girl. “I don’t mean to hurt her,” Sherman explained, “but will give her a scare.” When the search party reported back it was to say that Miss Zora M. Fair was not to be found. Her letter to Governor Brown would remain undelivered.

*

A few miles outside Covington, Mrs. Dolly Sumner Lunt Burge fell asleep fully dressed, expecting Yankees at any moment. During the day she had taken steps to protect her property by sending two of her mules into hiding and secreting food in different places. She also let her black coachman drive the forty fattened hogs she owned into the swamp for safekeeping. Now her only defense was with the Lord. “Oh, how I trust I am safe!” she prayed.

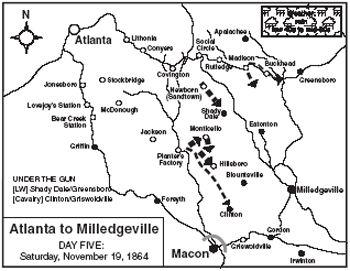

S

ATURDAY

, N

OVEMBER

19, 1864

Midnight–Noon

Right Wing

T

he combination of rain, bad roads, and congestion was turning the Right Wing’s crossing of the Ocmulgee River into a protracted ordeal. “We got up this morning wet & nasty,” groused an Illinoisan in the Fifteenth Corps. The “roads today are very slippery,” seconded an Iowan in the Seventeenth Corps, “which as the country is so hilly, makes difficult marching.” “On both sides of the stream, for many miles, the roads lay through low, flat ground, sodden with recent rains, and the heavy wagon trains soon converted them into almost bottomless abysses of mud, entailing upon the men severe labor in corduroying, and extricating artillery and wagon trains,” wrote a soldier in the 32nd Illinois. A member of the 4th Minnesota observed that the men’s “blankets are so wet and heavy that some of them could not be dried by fire and had to be left, being too heavy to carry, and so the boys will have to suffer and get along as best they can.”

In good weather the passage over the Ocmulgee would have been a matter of hours for the Right Wing’s 28,000 soldiers; instead it dragged on throughout the day, into the night, and would extend well into the next morning. Major General Howard opted to keep up the pressure

on Macon to divert attention from his increasingly exposed wagon train, which he later described as a “source of anxiety” for him. As the first elements of the Seventeenth Corps reached the small village of Monticello, they turned south and east toward Hillsboro, on the direct road to Macon. Also in motion as part of Howard’s diversionary scheme was Kilpatrick and his cavalry. This force, as Howard later reported, “as soon as over the river, again quickly turned down the first roads toward East Macon.”

The cavalry’s crossing of the Ocmulgee River took place before sunrise and was suitably dramatic. “Great fires were kept blazing on both banks of the river to light up the bridge,” recalled a trooper. “The light was so bright that it reflected the factory, and trees upon the banks, and the crossing columns of troops in the water as clearly and distinctly as if the river had been a mirror.” Getting over the broad stream was no mean feat. “The cavalry cross two by two, each trooper dismounted and leading his horse,” explained one of them. “The artillery, eight horses to a gun, sink the [pontoon] boats to within a few inches of the top, the bridge rising behind the gun as it goes from boat to boat.”

Left Wing

The Twentieth Corps, constituting the extreme northern flank of Sherman’s grand movement, passed through Madison today. First in line was Brigadier General John W. Geary’s division (the Second), which followed the railroad tracks eastward, on course for the Oconee River. “The weather is wet and disagreeable,” attested a Pennsylvania diarist. “Colored people are pleased to see the Yanks,” added an Ohio soldier. “Whites look sour & sad.” When the 111th Pennsylvania marched through Madison, their procession was subjected to a dour inspection by a group of old-timers. “A wag in Company A, at a moment when no sound was heard except the route step of marching feet, seeing the manifest distress of these white-bearded patriarchs, swung his cap and, looking at the group, shouted at the top of his voice, ‘Hurrah for

Lincoln!

’” chuckled a member of the regiment. “The old fellows nearly rolled off their chairs.”

Behind Geary’s men marched the Third Division, followed by the First, both of which turned south. Groups of soldiers operating ahead of the main column ran loose in the town for a while, leading an Illinois man to mutter that “our men ransacked it badly,” but order was quickly established so that the Yankees who followed almost all complimented what they saw. “It is the finest village this side of Nashville,” declared an Illinois man. “Yards full of the most beautiful roses and other plants.” A correspondent working for the

New York Herald

thought “the town looked too pretty to think of in connection with the march of an army.”

When the 102nd Illinois halted in the courthouse square, they were entertained by a band playing patriotic airs. “The men have obtained files of old papers, and are scattering them by hundreds through the different regiments,” wrote a member of the regiment. As a railroad depot, Madison had its share of legitimate targets. A deputation of town notables had tried to negotiate an exemption, but Slocum was not prepared to amend Sherman’s rules of war. “Cotton stored near the railroad station was fired, and the jail near the public square gave up its whips and paddles to increase the big bonfire in the public square,” noted an Ohioan. “The Calaboos[e] was burnt while the Bands plaid,”

recorded a Wisconsin diarist. Private houses in the village were subject to soldier searches, but were otherwise left alone.

The railroad agent’s wife (he was off in Savannah) pleaded with the Union boys not to burn her husband’s office. “But it was of no use whatever,” said a Connecticut soldier. “The windows were opened, fire thrown in and it was soon wrapped in flames. I almost always have sympathy for the women. But I did not much pity her. She was a regular secesh and spit out her spite and venom against the dirty Yanks and mudsills of the north.” Missed or ignored in the random searches was Edmund B. Walker’s coffin, which survived the Federal visit; many years later, young descendants would sneak into the attic to gawk at the space outlined in the dust indicating where it once rested.

Emma High’s resourceful mother produced her husband’s Masonic apron to back her request for help from any society member in the group of soldiers outside her home. An officer stepped forward, took charge, and posted a guard. Meanwhile, Emma watched, wide-eyed, as the young men in blue descended on her next-door neighbor’s flower garden. The plants, she recalled, were “stripped of all [their]…bright hued roses and the soldiers wove them into garlands and decorated their arms—crossed and tied them with the garlands, singing and making great sport of the occasion.”

Perhaps it was the beauty of the town that inspired Major General Slocum to indulge in a rare display of command prerogative by having a number of brigades pass before him in review. A soldier in the Third Brigade of the First Division remembered going through Madison in “fine style, colors flying[,] music playing[,] marching in column by platoon, and [being]…reviewed by Gen. Slocum as we passed the public square.” Another infantryman (Second Brigade, Third Division) recalled marching under Slocum’s gaze “with handsomely aligned ranks, precise movement and arms at right-shouldershift, the feet keeping step to the soul-stirring air of ‘Dixie.’”

The Second and Third brigades of the Third Division drew most of the railroad-wrecking assignment. “We spent the whole forenoon in tearing up the track,” recorded a soldier in the 85th Indiana. “It is rather interesting to see an army stack arms, step forward and take hold of the end of the ties and upset five miles of track at one lift.”

A few miles south and west of Madison, the Fourteenth Corps fin

ished passing through Covington, then turned southeast, toward a spot on the map called Shady Dale. The Second Division led the way, followed by the Third and the First. A

New York Herald

correspondent wrote that “the roads were found almost impassable from the rain that had fallen in torrents during the night.” An Ohio soldier never forgot moving “ahead in a heavy rain, the troops straggling much on account of a bad road.” The weather was making everyone grumpy. “You awake in the morning only to find yourself as lame & sore as ever,” grumbled an Ohioan. “Every step gives pain.”

The sound of rain drumming on his canvas tent fly greeted Major Hitchcock this morning. The commander of the Fourteenth Corps, Brevet Major General Jefferson C. Davis, stopped by to report that all his transportation and supplies were over the Alcovy River, and his rear guard was just getting across. This was more good news for Sherman, who outwardly remained a picture of confidence, though his mind never ceased mulling over probabilities and possibilities. Recorded Hitchcock, who treasured his close relationship with his boss, “the General explained today to me of his plans in any one of several contingencies.”

A few of the younger members of the headquarters entourage decided to improve their personal transportation by riding ahead of the column to find some horses and mules. Just before reaching the town of Newborn, the group was fired on from ambush, but their attackers fled almost as quickly as they had appeared. None in the party was hit, so they continued on their mission as if nothing had happened.

Confederate Lieutenant General William J. Hardee reached Macon this morning, endowed with Beauregard’s authority to take charge of the forces in the region. The intelligence that greeted his arrival was grim. As he promptly reported to Richmond: “The enemy [is] on both sides [of the] Ocmulgee River, about thirty miles from Macon. A column is reported near Social Circle marching on Augusta.” High on his to-do list was the urgent need to accumulate sufficient weapons to arm the militia forces gathering in Georgia and South Carolina. In a separate message Hardee telegraphed Richmond requesting that all “spare arms [be] sent to Charleston, S.C., subject to my orders.”

There was more bad news. Hardee had alerted Savannah to prepare its land side defenses, only to learn that the earthworks were incomplete and that much labor was needed to finish them. The officer in charge, Major General Lafayette McLaws, wanted to use his troops for the task, but Hardee told him “to press negroes if you need them.” On the plus side, during his train ride from Augusta to Macon, Hardee had passed over the long railroad bridge at the Oconee River and saw its strong defensive possibilities. He was now able to use his temporary authority to make certain that troops were directed to that potential choke point.

For his part, General Beauregard’s biggest struggle today was with his transportation. He departed Corinth, Mississippi, heading toward Mobile, Alabama, from where he hoped to find a train that would take him to Macon. He was frustrated that General Hood, headquartered in Florence, Alabama, still had not moved his army. Beauregard had reduced Hood’s options to two; he could either “divide [his force] and re-enforce Cobb [at Macon], or take the offensive [into Tennessee] immediately to relieve him.” Beauregard had no clue what Hood intended to do.

Despite these travails of the high command, Southern newspapers remained upbeat. According to the

Augusta Constitutionalist

, “After a careful survey of the topography of the country lying before SHERMAN, the distance he must travel before he can strike any vital point, and the difficulties that naturally environ an incursive army of that kind, we apprehend no serious result from the movement.” Editors were equally sanguine in the Confederate capital, where the writers for the

Richmond Dispatch

assured readers about Sherman that the “country cannot support him, and it is impossible he should carry more than ten or fifteen days’ supplies.” Looking to the illustrious leadership that was directing affairs in Georgia, the paper was positively bullish. “With such men at the head of such a force as we are informed Georgia can still furnish, it will be a very difficult job to march to Savannah, we should think.”

At Camp Lawton, outside Millen, Union prisoners crawled out from under whatever shelters they had managed to erect to protect themselves from the overnight rain. A half-ration of meal received yesterday evening was supplemented today with a load of beef heads, whose stink, related one captive, “would have turned our stomachs

under ordinary circumstances.” Those clever enough to have hidden money from spot searches did better. “Rice, bean soup, biscuits, pies and corn dodgers were made and sold on Market Street at exorbitant prices,” noted the POW.

Noon–Midnight

Left Wing

Pushing eastward along the Georgia Railroad, Brigadier General John Geary’s division (Twentieth Corps) reached Buckhead, where a small party of Rebel scouts was dispersed before the infantry set to wrecking things. “Burned many cotton mills and presses,” noted an Ohio diarist, “took dinner at Buckhead station[,] burned the station.” Geary later supplied a bit more detail when he reported destroying “the water-tank, [a] stationary engine, and all the railroad buildings.” A Pennsylvania soldier recalled burning “several thousand bushels of corn,” while a New Yorker reported having “a first rate time killing hogs and getting potatoes.”