She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth (6 page)

Read She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth Online

Authors: Helen Castor

By this argument, then, any exercise of power by a woman was a manifestation of the female propensity for sin; and the Old Testament offered a ready identification of female rule as a sexualised tyranny in the infamous figure of Jezebel, wife of King Ahab, who exploited her hold over her husband and their two sons to turn Israel away from God and subject its people to immorality and injustice. ‘Such as ruled and were queens were for the most part wicked, ungodly, superstitious, and given to idolatry and to all filthy abominations, as we may see in the histories of Queen Jezebel…’ wrote Thomas Becon, a Protestant preacher and homilist, in 1554. Knox, whose favoured rhetorical mode inclined markedly toward fire and brimstone, tackled the subject with obvious relish: ‘Jezebel may for a time sleep quietly in the bed of her fornication and whoredom, she may teach and deceive for a season; but neither shall she preserve herself, neither yet her adulterous children from great affliction, and from the sword of God’s vengeance …’ And Knox’s blasting trumpet was directed not only at women who sought to rule in their own right, but also at those whose authority, like that of Jezebel herself, depended on their husbands and sons.

The example of the medieval queens who had exercised power in England in previous centuries, therefore, was both complex and troubling, even for those who had no wish to emulate Knox and his colleagues in the articulation of polemical absolutes. A woman could not easily fit the role of a monarch, moulded as it was for a man. Nor could a wife or mother step forward to act in place of a husband or son without raising questions about the nature of her rule and its place in the right order of creation. But shedding the she-wolf’s skin would come at a price: the ‘good woman’ who

acknowledged her duty of obedience and the primacy of her role as a helpmeet could not, after all, hope to offer sustained political leadership in any meaningful sense.

For the Tudor women confronting the succession crisis of 1553, then, the battle to secure the throne was only the first step on a hard road ahead. Their right to wear the crown would not go unquestioned, but that challenge was finite and graspable compared to the test which the exercise of power would present. In facing that greater test, they had every reason not to look back to their medieval forebears. Those earlier queens had been compromised by the provisional nature of their authority, and condemned by history for their unnatural self-assertion. No self-respecting Tudor monarch – self-evidently, of course, fit to rule by God-given right – would need to acknowledge such problematic exemplars. It was to kings, not queens, that Tudor sovereigns looked for example and warning. (‘I am Richard II, know ye not that?’ Elizabeth sharply remarked in response to Shakespeare’s meditation on the nature of kingship.)

But that very identification with male sovereignty emphasises what the Tudor queens shared with the women who had held power in the centuries before them. In the lives of those women – in their ambitions and achievements, their frustrations and failures, the challenges they faced and the compromises they made – were laid out the lineaments of the paradox which the female heirs to the Tudor throne had no choice but to negotiate. Man was the head of woman; and the king was the head of all. How, then, could royal power lie in female hands?

Lady of England

1102–1167

On 1 December 1135, another king of England lay dying. Not a boy but a man of nearly seventy, Henry I had ruled the English people for more than half his lifetime. A bull-like figure, stocky and powerfully muscular, Henry was a commanding leader, ‘the greatest of kings’, according to the chronicler Orderic Vitalis, who observed his rule admiringly from the cloisters of a Norman monastery. His greatness did not lie on the battlefield – a competent rather than exceptional soldier, Henry avoided all-out warfare where he could – but in his judgement, his charisma and his acute political brain. Nor had age dimmed his relentless energy; he had spent the summer and autumn of 1135 on military patrol along the borders of his lands, and in November he rode to his lodge at Lyons-la-Forêt, thirty miles east of Rouen, for the restorative pleasures of a hunting trip.

But while he was there, against his doctor’s orders, the king indulged in a dish of lampreys, an eel-like fish that was prized as a delicacy, served in a pie powdered with spices or roasted with a sauce of blood and wine infused with ginger, cinnamon and cloves. Perhaps his physician was right about the indigestible richness of the dish; perhaps the lampreys were dangerously unfresh; or perhaps the illness by which Henry was struck that night was no more than unhappy coincidence. Whatever the cause, within a couple of days it was clear that he was unlikely to survive. As in 1553, a king’s mortality brought great men scrambling to his bedside, and the succession to his throne became a matter of frantic political speculation.

The country whose rule Henry was about to relinquish would not have been wholly familiar to his Tudor descendants. England

in 1135 was a young kingdom – or, rather, an old kingdom in the upstart hands of a new royal dynasty. There had been a king of all England for two hundred years, ever since the independent Anglo-Saxon territories of Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex and East Anglia had first been united under Æthelstan, grandson of the great King Alfred. Despite the repeated shockwaves of Viking assaults on this newly unified land – assaults so successful that the English throne was appropriated for a time by the Danish King Cnut – Anglo-Saxon England had grown by the mid-eleventh century into a remarkably powerful, wealthy and sophisticated state. And then, on 14 October 1066, on a sloping field six miles north of Hastings, the flower of the Saxon aristocracy was cut down by charging horsemen under the command of Henry’s father, William, duke of Normandy.

William claimed to be the rightful heir of the Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor, but the Norman conquest of England that followed the slaughter at Hastings was nothing less than a revolution. The Anglo-Saxon political caste was systematically eliminated, as four or five thousand thegns – the great Anglo-Saxon landholders – were violently displaced by a new elite of fewer than two hundred Norman barons. French, not English, was now the language of power in England. And this political year zero opened the way for a new kind of kingship, too. The evolutionary intricacies of Anglo-Saxon landholding were swept away by William’s irruption into the political landscape. England was now the personal property of its conqueror, to be parcelled out at will among his loyal supporters through a chain of feudal relationships, where land was granted from lord to vassal in return for an oath of personal fidelity and a pledge of military service. Such relationships were the currency of politics throughout western Europe, but only in England, on a blank slate wiped clean by conquest, could the king create a feudal hierarchy depending directly on his own authority, untrammelled by customary rights and local tradition.

England, however, was only one part of the Conqueror’s domains. After 1066, the Channel was no longer a frontier but

a thoroughfare, carrying William and his most powerful subjects between the lands they now held on both sides of the sea. In England, he was a king, imposing his royal will on a vanquished people. In Normandy, on the other hand, he remained a duke – not a sovereign lord but a vassal of the king of France. In practice, Philippe I had little hold on his nominal liegeman: he could not come close to matching the military might that had enabled William to seize the English crown, nor could he escape the constraints of custom and precedent that William’s invasion had obliterated on the other side of the Channel. Nevertheless, questions remained about how the new Norman kingdom of England might fit within a map of Europe which was composed not of neatly interlocking nation-states behind precisely defined borders, but of a constantly shifting web of overlapping jurisdictions, alliances and allegiances.

Henry was the third Norman monarch to wield this double authority, after his formidable father and his dandified, overconfident brother William, known as ‘Rufus’ because of his ruddy complexion. A child of the Conquest, born in Yorkshire two years after his father’s triumph at Hastings, Henry personified the hybrid complexities of the Anglo-Norman world. He was educated in England, but – like the Conqueror, who briefly tried to learn English before giving it up as a bad job – Henry thought and spoke in Norman French. The two greatest contemporary historians who recorded his exploits and revered his kingship, Orderic Vitalis and William of Malmesbury, were each the son of a Norman father and an English mother, one writing in the Norman monastery of St Evroult, the other at Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire. And now, in December 1135, Henry’s English birth would be followed by a Norman death, as he made his final confession and received the last rites at Lyons-la-Forêt.

Despite the hush of the room and the spiritual ministrations of the archbishop of Rouen, the king’s energetic mind could not find peace in his final hours. His overwhelming preoccupation, as it had been for the last fifteen years of his life, was the question of who should succeed him – and he had good reason to be anxious.

In the seventy years of its existence, Norman England had not yet settled on a means of determining the identity of a new king. Before 1066, the Anglo-Saxons had looked to the Witan, the great nobles of the realm, to choose the man best suited to lead them from among the Æthelings, direct royal descendants of the sixth-century warrior Cerdic, first Saxon king of Wessex. In Normandy, meanwhile, the duke himself had traditionally nominated his own heir – in practice, almost always his eldest son – to whom his magnates then swore fidelity and allegiance.

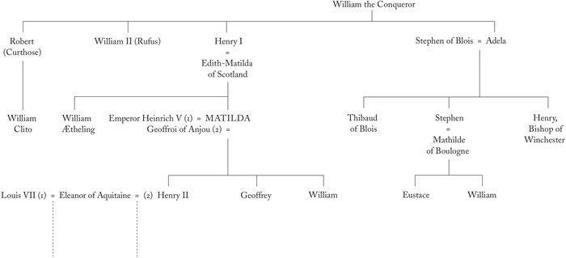

That was the way in which the Conqueror had become duke of Normandy, at the age of only seven, and he had followed Norman custom in designating as his successor there his eldest son Robert, known as Curthose – ‘short shanks’ – or, more contemptuously still, Gambaron – ‘fat legs’ – because of his low stature. In England, however, William was not bound by precedent, whether Norman or Anglo-Saxon. And for the last four years of his life, the king and his eldest son had been acrimoniously estranged. In September 1087, when William – now a corpulent but still powerfully imposing man of sixty – lay on his deathbed, he was grudgingly prepared to concede that Robert should rule in Normandy, as he had promised more than twenty years earlier. But in England, he intended that the crown should pass to his second and favourite son, William Rufus, who was despatched from his father’s bedside at Rouen across the Channel to Westminster. There Rufus was crowned king little more than two weeks after his father’s death.

The result was war. Robert could not accept that his younger brother should supplant him in England, while Rufus set his sights on adding his elder brother’s duchy to his new kingdom. Sporadic fighting and tension-filled truces left Rufus – who was a better soldier and a shrewder leader than his unimpressive brother – with the upper hand, until in 1096 Robert abandoned the struggle, pawning Normandy to Rufus for a cash payment of ten thousand silver marks to fund his departure on crusade.