She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth (2 page)

Read She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth Online

Authors: Helen Castor

The book is dedicated to two of the most inspiring history teachers I could ever have wished for.

The boy in the bed was just fifteen years old. He had been handsome, perhaps even recently; but now his face was swollen and disfigured by disease, and by the treatments his doctors had prescribed in the attempt to ward off its ravages. Their failure could no longer be mistaken. The hollow grey eyes were ringed with red, and the livid skin, once fashionably translucent, was blotched with sores. The harrowing, bloody cough, which for months had been exhaustingly relentless, suddenly seemed more frightening still by its absence: each shallow breath now exacted a perceptible physical cost. The few remaining wisps of fair hair clinging to the exposed scalp were damp with sweat, and the distended fingers convulsively clutching the fine linen sheets were nailless, gangrenous stumps. Edward VI, by the grace of God King of England, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, and Supreme Head of the Church of England, was dying.

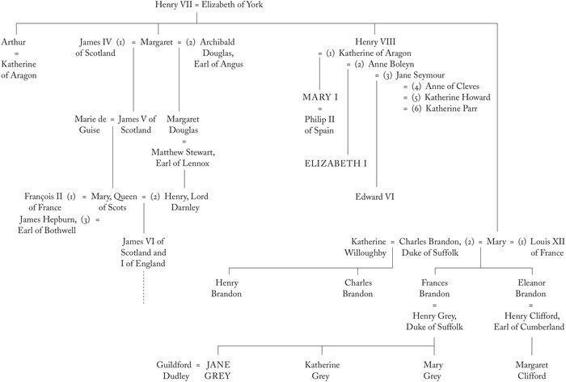

He was the youngest child of Henry VIII, that monstrously charismatic king whose obsessive quest for an heir had transformed the spiritual and political landscape of his kingdom. Of the boy’s ten older siblings, seven had died in the womb or as newborn infants. One brother, a bastard named Henry Fitzroy – created duke of Richmond and Somerset, earl of Nottingham, lord admiral of England, and head of the Council of the North at the age of six by his doting father – reached his seventeenth birthday before succumbing to a pulmonary infection in the year before Edward’s birth. His two surviving half-sisters, pale, pious Mary and black-eyed, sharp-witted Elizabeth, had each been welcomed into the world with feasts, bells and bonfires as the heir to the Tudor throne; but they were declared illegitimate – Mary

at seventeen, Elizabeth as a two-year-old toddler – when Henry repudiated each of their mothers in turn.

When Edward was born in the early hours of 12 October 1537, therefore, he was not simply the king’s only son, but the only one of Henry’s children whose legitimacy was undisputed. ‘England’s Treasure’, the panegyrists called him, and Henry lavished every care on the safekeeping of his ‘most precious jewel’. By the age of eighteen months, the prince had his own household complete with chamberlain, vice-chamberlain, steward and cofferer, as well as a governess, nurse and four ‘rockers’ of the royal cradle, all sworn to maintain a meticulous regime of hygiene and security around their young charge. If the king could do nothing to alter the fact that Edward was motherless – Jane Seymour, Henry’s third queen, had sat in state at her son’s torch-lit christening three days after his birth, but died less than a fortnight later – he did eventually provide him with a stepmother whose intelligence and kindness touched a deep chord with the boy. Katherine Parr, the king’s sixth wife, was a clever, vivacious and humane woman who befriended all three of the royal children. She was already close to Princess Mary, whom she had previously served as a lady-in-waiting; and to nine-year-old Elizabeth and five-year-old Edward she brought a maternal warmth they had never before known, encouraging their intellectual development and enfolding them within a passable facsimile of functional family life. ‘

Mater carissima

’, Edward called her, ‘my dearest mother’, who held ‘the chief place in my heart’.

But Henry died, a decaying, bloated hulk, in January 1547. Nor could Edward, king at nine, depend on the continuing support of his beloved stepmother. The bond of trust between them was broken only four months after his father’s death by Katherine’s impetuous remarriage to his maternal uncle, the dashing Thomas Seymour. She died little more than a year later after giving birth to her only child, a short-lived daughter named Mary. The young king now found his family fragmenting around him. Thomas Seymour, reckless and restlessly ambitious, was brought down by

his own extravagant plotting six months after the loss of his wife. He was convicted of treason and executed in March 1549 on the authority of the protectorate regime led by his brother, the duke of Somerset. Just seven months later, Somerset himself fell from power, and was beheaded on Tower Hill in January 1552.

Edward had lost his father, stepmother and two uncles in the space of five years. He still had his half-sisters, but his dealings were straightforward with neither of them. He and Mary, twenty-one years his senior, were touchingly fond of one another; but they were irrevocably estranged as a result of the religious upheavals precipitated by their father’s convoluted matrimonial history. In 1527, Henry had been implacably determined to annul his marriage to his first wife, Mary’s mother, Katherine of Aragon. But the pope – at that moment barricaded within the Castel Sant’Angelo while Rome was sacked by the forces of Katherine’s nephew, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V – had been in no position to grant Henry the divorce he so urgently desired. And if papal authority would not sanction the dictates of Henry’s conscience, then papal authority, Henry believed, could no longer be sanctioned by God. Convinced that the blessing of a son and heir had been denied him because his union with Katherine was tainted by her previous marriage to his brother Arthur – and intent on begetting such a blessing on the bewitching form of Anne Boleyn – Henry broke with Rome, and declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England.

For the king, this was a matter of jurisdiction, not doctrine. In terms of the fundamental tenets of his faith, Henry remained a Catholic to the end of his life. But, with the ideas of Protestant reformers gaining currency across Europe, it proved impossible to hold the line that the new English Church was simply a form of orthodox Catholicism without the pope. Few of his subjects who shared Henry’s doctrinal conservatism found it as easy as their king to discard the spiritual power of the ‘bishop of Rome’. Meanwhile, the most fervent support for the royal supremacy came from those who wished for more sweeping religious change.

Thus it was that Edward’s education was entrusted to Protestant sympathisers. Henry, of course, expected them to subscribe exactly to his own idiosyncratic brand of portmanteau theology, but their influence on a boy who later described the pope as ‘the true son of the devil, a bad man, an Antichrist and abominable tyrant’ was unmistakable. Mary, on the other hand, had been brought up a generation earlier, when her father was still engaged in defending the faith of Rome against the challenge of the apostate Luther. The new religion espoused by her brother could be nothing but anathema to her, when vindication of her mother’s honour and of her own legitimacy was inextricably bound up with adherence to papal authority. From 1550, their mutual intransigence embroiled them in a bitter wrangle over Mary’s insistence on celebrating mass in her household, in open defiance of the proscriptions of Edward’s Protestant government.

Between Edward and Elizabeth, there was no such spiritual breach. Elizabeth was the living embodiment of the Henrician Reformation – the baby born to Anne Boleyn after Henry had used his new powers as Supreme Head of his own Church to secure the divorce which the pope had refused him. Just as attachment to Rome was an indissoluble part of Mary’s heritage, so separation from it was of Elizabeth’s. And, like Edward, she had been exposed to the ‘new learning’ both in her humanist-inspired education and through the evangelical influences in Katherine Parr’s lively household. Conforming to the Protestant reformation instituted by Edward’s ministers therefore presented Elizabeth with no crisis of conscience. The teenage princess adopted the plain, unadorned dress commended by the reformers with such austerity that Edward called her ‘my sweet sister Temperance’. (More cynical observers noted not only the political expediency of this ostentatious godliness, but also how well the simple style suited her youth and striking looks – a conspicuous contrast to the unflattering effect of the heavily jewelled costumes favoured by thirty-five-year-old Mary).

But Elizabeth’s subtle intelligence was of a different stamp from the deeply felt, dogmatic piety of her brother and sister, albeit

that this temperamental resemblance between Edward and Mary left them stranded on opposite sides of an unbridgeable religious divide. Elizabeth was cautious, pragmatic and watchful, acutely aware of the threatening instability of a world in which her father had ordered the judicial murder of her mother before her third birthday. She had no memory of a time when her own status and security had not been at best contingent, and at worst explicitly precarious. As a result, she conducted her political relationships and religious devotions with diplomatic flexibility, rather than the emotional absolutism of her siblings. (‘This day’, she said when told of the execution of Thomas Seymour, ‘died a man with much wit and very little judgement’ – a shrewd and startlingly opaque response from a fifteen-year-old girl who had not been immune to Seymour’s charms, and had only narrowly avoided fatal entanglement in his grandiose schemes.)

Despite their ostensible religious compatibility, then, Edward and Elizabeth were not close. They had been brought together in January 1547 to be told of their father’s death – and clung to one another, sobbing at the news – but saw each other only rarely in the years that followed. Still, if the young king lacked the emotional and political support of immediate relatives at his court, it hardly mattered, given that Edward would one day surely marry and father a family of his own. He had been formally betrothed in 1543, at the age of five, to his seven-month-old cousin Mary Stuart, the infant queen of Scotland. But the Scots were unhappy about the implications of this matrimonial deal – which threatened to subject Scotland to English rule – for the same reason that the English were keen to pursue it. Unsurprisingly, the Scots resisted subsequent attempts to enforce the treaty through the ‘rough wooing’ of an English army laying waste to the Scottish lowlands, and in 1548 Mary was instead taken to Paris to renew the ‘Auld Alliance’ between Scotland and France by marrying the four-year-old dauphin, heir to the French throne.

A French bride – the dauphin’s sister Elisabeth – was later proposed for Edward himself; but in the meantime he found

friendship within his household, in the boys who shared his education. His closest companions were Henry Sidney, whose father was steward of Edward’s household; Sidney’s cousins Henry Brandon, the young duke of Suffolk, and his brother Charles; and Barnaby Fitzpatrick, son and heir of an impoverished Irish lord. In 1551 Fitzpatrick was sent to France to complete his training as a courtier and a soldier, but Edward maintained an affectionate correspondence with his ‘dearest and most loving friend’ – even if Barnaby failed to comply with some of the king’s more serious-minded requests; ‘… to the intent we would see how you profit in the French,’ Edward wrote earnestly, ‘we would be glad to receive some letters from you in the French tongue, and we would write to you again therein’.

The young king and his friends were taught by some of the finest humanist scholars in England. Edward mastered Latin before he reached his tenth birthday. Not only could he converse eloquently in the language and compose formal Latin prose, but he read and memorised volumes of classical and scriptural texts. In the years that followed, he acquired a fluent command of Greek and French, and at least a smattering of Italian and Spanish, through training which was not only linguistic but rhetorical, philosophical and theological. His reading of Cicero, Plato, Aristotle, Plutarch, Herodotus and Thucydides provided the intellectual basis for his weekly

oratio

, an essay in the form of a declamation, written alternately in Greek and Latin, which he was required to deliver in front of his tutors each Sunday. He studied mathematics and astronomy, cartography and navigation, politics and military strategy, and music, learning to play both the virginals and the lute.