She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth (78 page)

Read She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth Online

Authors: Helen Castor

A conventional image of virtuous queenship at odds with Margaret of Anjou’s later reputation as Shakespeare’s ‘She-wolf of France’: Margaret sits in a consort’s place on the left of her husband, Henry VI, to receive from John Talbot, earl of Shrewsbury, a gift of the book in which this illumination appears.

King Edward VI, a slightly built teenager trying to emulate the imposing style of his father Henry VIII; and a posthumous portrait of Edward’s cousin Lady Jane Grey.

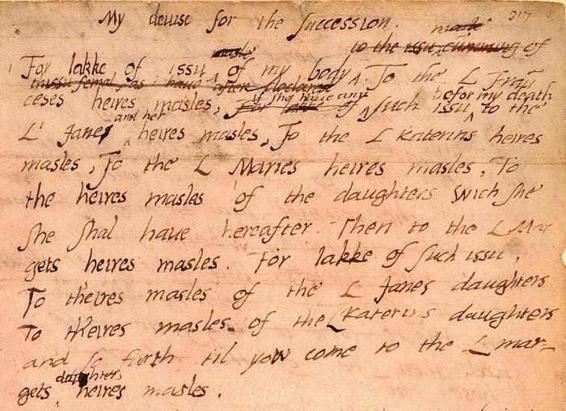

Edward’s ‘device for the succession’, drafted in his own hand, which specified that England’s future monarchs should be Protestant and male. During his final illness in 1553, Edward named Jane his heir by changing his bequest of the crown: ‘to the L’ Janes heires masles’ became ‘to the L’ Janes

and her

heires masles’.

Mary Tudor in 1554, when, according to the outgoing Venetian ambassador Giacomo Soranzo, the queen was ‘of low stature, with a red and white complexion, and very thin; … were not her age on the decline she might be called handsome rather than the contrary’.

An improvised division of royal labour on the Great Seal of England, 1554: Mary rides ahead, holding the sceptre and looking back at her husband, King Philip, who takes the consort’s position on her left with a sword unsheathed in his hand.

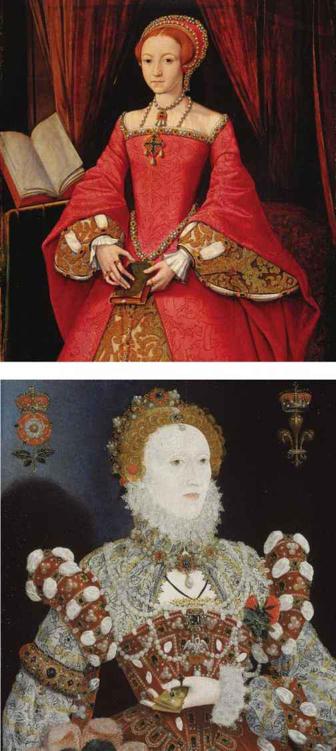

From human being to icon. Top, Elizabeth at thirteen, a study in charismatic self-possession. Below, the queen at forty-two, a stylised figure decked about with symbols: flanked by the Tudor rose, representing the crown of England, and the fleur-de-lys for her claim to France, Elizabeth wears pinned to her bodice an enamelled pelican, a symbol of mystical and selfless motherhood – and therefore of the queen as mother of her people – because it was believed to feed its young with blood pecked from its own breast.

Apotheosis of an icon: Elizabeth at sixty-six. Goddess-like in her eternal youth, she has a serpent on her sleeve for wisdom, and a rainbow in her hand for the peace and prosperity brought by the sunlight of her majesty, while the eyes and ears on her cloak show that she sees and hears all. The knotted pearls that represent her virginity both emphasise and defend her sexual power. The lesson of this eclectic and densely woven imagery was that, if women were lesser beings and unfit to rule, England’s queen was a unique and glorious exception.