Red Capitalism (32 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

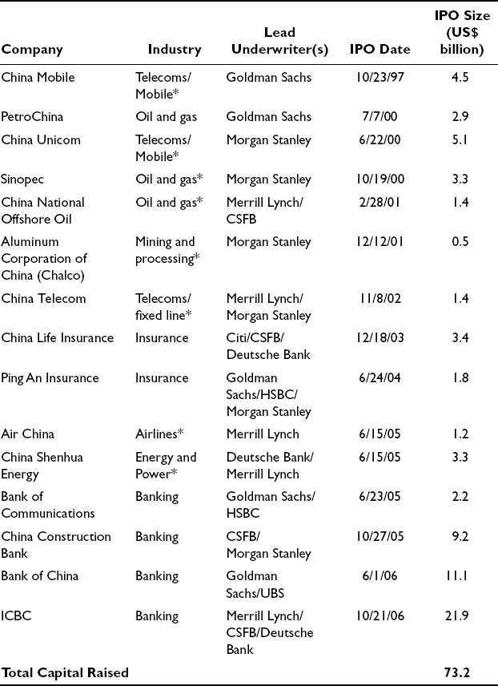

TABLE 6.6

The National Team: Overseas IPOs, 1997–2006

Source: Wind Information

Note: * denotes company parent Chairman is on the central nomenklatura list of the Organization Department of the Communist Party of China.

None of this would have been possible if it had not been for international, particularly American, investment bankers. Over the period 1997–2006, bankers and professionals from a small number of international legal and accounting companies played major roles in the creation of entire new companies. These companies were created out of industries that were fragmented, lacking economies of scale, or, in the case of the banks, even publicly acknowledged as being bankrupt. The investment banks put their reputations on the line by sponsoring these companies in the global capital markets, introducing them to money managers, pension funds and a myriad of other institutional investors. Supported by global sales forces, industry analysts, equity analysts and economists, the banks sold these companies for China. Sometimes investors were so excited they didn’t even have to: for the first time, global investors had the opportunity to invest in true proxies of China’s national economy.

Simply put, international financial, legal and accounting rules provided the creative catalyst for China’s vaunted National Team. Even more important, their professional expertise and skills put Beijing and the Communist Party of China in the driver’s seat for a strategic piece of the Chinese economy for the first time ever: the central government and the Party’s Organization Department own the National Team.

ENDNOTES

1

Shares in the public offering are allocated to investors by means of a lottery process.

2

Of course, the authors are well aware that the Hong Kong Shanghai Bank and AIG are companies with deep Chinese roots, but they were not Chinese owned.

3

For more details on how the demand for capital gave rise to stock markets spontaneously in China during the early 1980s, see Walter and Howie 2006: Chapter 1.

4

See David Faure,

China and Capitalism: A history of business enterprise in modern China

. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006.

CHAPTER 7

The National Team and China’s Government

“The source of crony capitalism in China is the unrestrained power held by certain factions that lets them intervene in economic activity and allocate resources. Supporters of the old economy want to increase SOE monopoly power and strengthen government’s dictatorial power.”

Wu Jinglian, Caijing

September 28, 2009

There can be little doubt that the Chinese government’s initial policy objective was to create a group of companies that could compete globally. However, the National Team created by government policy was, from its inception, more politically than economically competitive and, as a consequence, these oligopolies came to own the government. At the same time, that bankers were creating National Champions, Zhu Rongji was, perhaps inadvertently, making it possible for these huge corporations to displace the government. In 1998, Premier Zhu forcefully carried out a major streamlining of central government agencies that reduced their staffing by over 50 percent and eliminated the great industrial ministries that had been created to support the Soviet-inspired planned economy. These included the Ministry of Coal Industry, the Ministry of Machine-Building, the Ministry of Metallurgy, the Ministry of Petroleum, the Ministry of Chemicals, and the Ministry of Power, all of which became small bureaus that were meant to regulate the newly created companies in their sectors. The new companies and the bureaus were collected under the now long-forgotten State Economic and Trade Commission (SETC).

1

The ministries disappeared, the SETC was again reorganized, but the companies remained. Then, in 2004, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) was created to bring order to the ownership of state enterprises. The SASAC was meant to be the owner of the major central SOEs on behalf of the state, and was endorsed as such by the State Council. But it has largely been a failure precisely because it was based on Soviet-inspired, top-down, organizational principles. Because of the stock markets, China in the twenty-first century has progressed far beyond this to the point where Western notions of enterprise ownership are used to trump the interests of the state. To illustrate this point, the SASAC’s relationship with its collection of central SOEs is contrasted to Central Huijin’s investments in China’s major financial institutions.

ZHU RONGJI’S GIFT: ORGANIZATIONAL STREAMLINING, 1998

The regulatory bureaus with which Zhu replaced the great ministries had far fewer staff than their predecessors. Even worse, their heads were not ministers, and lacked the seniority to speak directly to the chairmen and CEOs of the major corporations, who were, in many cases, the former ministry bosses of those left behind in the bureaus. In other words, by eliminating the industrial ministries and at the same time promoting the creation of the huge National Champions, Zhu Rongji effectively changed the ministries into Western-style corporations that were staffed by the same people at the top. However, he did not, or was unable to, change the substance.

That may have been because the former ministry officials now in charge of the new corporations successfully fought for the right to remain on the critical staffing hierarchy of the Chinese Communist Party. This would seem entirely natural given the Party’s desire to ensure its control over the economy. However, had these new corporations been staffed by men who were outside of the Party’s

nomenklatura

, things might have turned out differently and the political independence of the Party and government might have been preserved.

There was one crucial exception: in spite of all the financial clout they seem to wield, the Big 4 banks remain classified as only vice-ministerial entities. An entity is placed in the state organizational hierarchy based on the rank of its highest official; the chairmen/CEOs of these banks carry only a rank of vice-minister. The reason for this exception appears to be straightforward: the Party seems to have wanted to ensure that the banks remained subordinate entities, and not just to the State Council, but to the major SOEs as well. Banks were a mechanical financial facilitator in the Soviet system; the main focus of economic effort then was on the enterprises. Little has changed.

When transferring to these central SOEs (

yangqi ) the former ministry officials were able to retain their positions on the Party list controlled by the central Organization Department. Today, 54 of the 100-plus central SOEs nominally managed by the SASAC are on what is called the central

) the former ministry officials were able to retain their positions on the Party list controlled by the central Organization Department. Today, 54 of the 100-plus central SOEs nominally managed by the SASAC are on what is called the central

nomenklatura

list. The chairmen/CEOs of these companies hold ministerial rank and are appointed directly by the Organization Department.

2

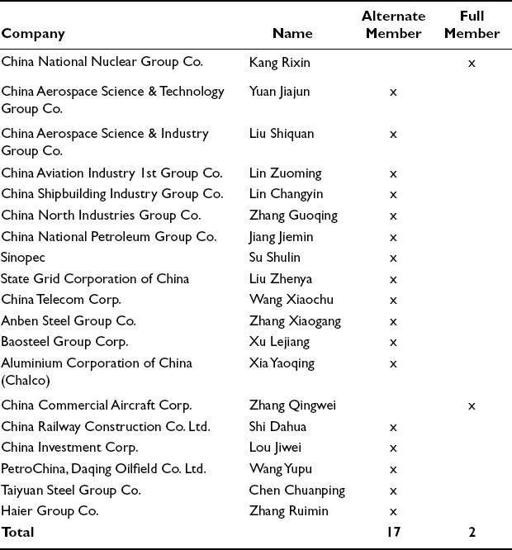

These men rank equally with provincial governors and all ministers on China’s State Council, and many are members or alternates of the powerful Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (see

Table 7.1

). What would the chairman of China’s largest bank do if the chairman of PetroChina asked for a loan? He would say: “Thank you very much, how much, and for how long?”

TABLE 7.1

The National Team: Representation on the Central Committee (2009)

Source: Kjeld Erik Brodsgaard, “Politics and business group formation in China,” unpublished manuscript, April 2010

What then of the SASAC, the current entity charged with overseeing the central SOEs? The SASAC was established by the State Council in 2003 and had been created out of the SETC (see Endnote 1) and an agglomeration of other commissions and bureaus which previously had oversight of the central SOEs. It was created as a quasi-governmental entity (

shiye danwei ) rather than a government ministry because such a powerful government entity would have attracted discussion at China’s “highest organ of state power,” the National People’s Congress (NPC). This was particularly so since there was a line of argument in support of the NPC as the proper entity to own state assets. This argument held that since the NPC was, in fact, the legal representative of “the whole people” under the Constitution, it was better placed than the State Council to play this role. As a result, the entire process establishing the SASAC was rushed through just before the NPC convened in March 2003.

) rather than a government ministry because such a powerful government entity would have attracted discussion at China’s “highest organ of state power,” the National People’s Congress (NPC). This was particularly so since there was a line of argument in support of the NPC as the proper entity to own state assets. This argument held that since the NPC was, in fact, the legal representative of “the whole people” under the Constitution, it was better placed than the State Council to play this role. As a result, the entire process establishing the SASAC was rushed through just before the NPC convened in March 2003.

One of the greatest considerations surrounded the issue of the new commission’s classification (

guige ). For a moment it appeared that it would be similar to the Central Work Committee for Large Enterprises (

). For a moment it appeared that it would be similar to the Central Work Committee for Large Enterprises (

daqi gongwei ), the other of the SASAC’s two principal components, which was headed by a Party member at vice-premier level. The other choice was the arrangement at the SETC, with a ministry-level leader at the top. The final choice of the latter was a decision that weakened the SASAC almost fatally from the very beginning. Why should a major corporation owned by the Chinese central

), the other of the SASAC’s two principal components, which was headed by a Party member at vice-premier level. The other choice was the arrangement at the SETC, with a ministry-level leader at the top. The final choice of the latter was a decision that weakened the SASAC almost fatally from the very beginning. Why should a major corporation owned by the Chinese central

government

be subject to the authority of what in the Chinese context is tantamount to a

non-government

organization (NGO) even if it was run by a minister? A vice-premier might have made the key difference.