Programming Python (56 page)

tkinter GUIs always

have an application root window, whether you get it by

default or create it explicitly by calling theTkobject constructor. This main root window is

the one that opens when your program runs, and it is where you generally

pack your most important and long-lived widgets. In addition, tkinter

scripts can create any number of independent windows, generated and popped

up on demand, by creatingToplevelwidget objects.

EachToplevelobject created

produces a new window on the display and automatically adds it to the

program’s GUI event-loop processing stream (you don’t need to call themainloopmethod of new windows to

activate them).

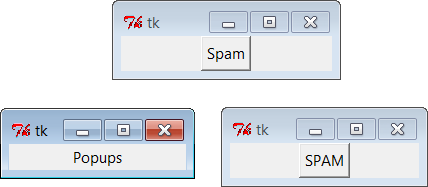

Example 8-3

builds a root and two pop-up windows.

Example 8-3. PP4E\Gui\Tour\toplevel0.py

import sys

from tkinter import Toplevel, Button, Label

win1 = Toplevel() # two independent windows

win2 = Toplevel() # but part of same process

Button(win1, text='Spam', command=sys.exit).pack()

Button(win2, text='SPAM', command=sys.exit).pack()

Label(text='Popups').pack() # on default Tk() root window

win1.mainloop()

The

toplevel0

script gets a root window by

default (that’s what theLabelis

attached to, since it doesn’t specify a real parent), but it also creates

two standaloneToplevelwindows that

appear and function independently of the root window, as seen in

Figure 8-3

.

Figure 8-3. Two Toplevel windows and a root window

The twoToplevelwindows on the

right are full-fledged windows; they can be independently iconified,

maximized, and so on.Toplevels are

typically used to implement multiple-window displays and pop-up modal and

nonmodal dialogs (more on dialogs in the next section). They stay up until

they are explicitly destroyed or until the application that created them

exits.

In fact, as coded here, pressing theXin the upper right corner of either of theToplevelwindows kills that window only. On

the other hand, the entire program and all it remaining windows are closed

if you press either of the created buttons or the main window’sX(more on shutdown protocols in a

moment).

It’s important to know that althoughToplevels are independently active windows, they

are not separate processes; if your program exits, all of its windows are

erased, including allToplevelwindows

it may have created. We’ll learn how to work around this rule later by

launching independent GUI programs.

AToplevelis roughly like aFramethat is split off into its own

window and has additional methods that allow you to deal with top-level

window properties. TheTkwidget is roughly

like aToplevel, but it is used to

represent the application root window.Toplevelwindows have parents, butTkwindows do not—they are the true roots of

the widget hierarchies we build when making tkinter GUIs.

We got aTkroot for free in

Example 8-3

because theLabelhad a default parent,

designated by not having a widget in the first argument of its

constructor call:

Label(text='Popups').pack() # on default Tk() root window

PassingNoneto a widget

constructor’s first argument (or to itsmasterkeyword argument) has the same

default-parent effect. In other scripts, we’ve made theTkroot more explicit by creating it directly,

like this:

root = Tk()

Label(root, text='Popups').pack() # on explicit Tk() root window

root.mainloop()

In fact, because tkinter GUIs are a hierarchy, by default you

always

get at least oneTkroot window, whether it is named

explicitly, as here, or not. Though not typical, there may be more than

oneTkroot if you make them

manually, and a program ends if all itsTkwindows are closed. The firstTktop-level window created—whether explicitly

by your code, or automatically by Python when needed—is used as the

default parent window of widgets and other windows if no parent is

provided.

You should generally use theTkroot window to display top-level information of some sort. If you don’t

attach widgets to the root, it may show up as an odd empty window when

you run your script (often because you used the default parent

unintentionally in your code by omitting a widget’s parent and didn’t

pack widgets attached to it). Technically, you can suppress the default

root creation logic and make multiple root windows with theTkwidget, as in

Example 8-4

.

Example 8-4. PP4E\Gui\Tour\toplevel1.py

import tkinter

from tkinter import Tk, Button

tkinter.NoDefaultRoot()

win1 = Tk() # two independent root windows

win2 = Tk()

Button(win1, text='Spam', command=win1.destroy).pack()

Button(win2, text='SPAM', command=win2.destroy).pack()

win1.mainloop()

When run, this script displays the two pop-up windows of the

screenshot in

Figure 8-3

only (there is no third root window). But it’s more common to use theTkroot as a main window and createToplevelwidgets for an application’s

pop-up windows. Notice how this GUI’s windows use a window’sdestroymethod to close just one window,

instead ofsys.exitto shut down the

entire program; to see how this method really does its work, let’s move

on to window protocols.

BothTkandToplevelwidgets

export extra methods and features tailored for their

top-level role, as illustrated in

Example 8-5

.

Example 8-5. PP4E\Gui\Tour\toplevel2.py

"""

pop up three new windows, with style

destroy() kills one window, quit() kills all windows and app (ends mainloop);

top-level windows have title, icon, iconify/deiconify and protocol for wm events;

there always is an application root window, whether by default or created as an

explicit Tk() object; all top-level windows are containers, but they are never

packed/gridded; Toplevel is like Frame, but a new window, and can have a menu;

"""

from tkinter import *

root = Tk() # explicit root

trees = [('The Larch!', 'light blue'),

('The Pine!', 'light green'),

('The Giant Redwood!', 'red')]

for (tree, color) in trees:

win = Toplevel(root) # new window

win.title('Sing...') # set border

win.protocol('WM_DELETE_WINDOW', lambda:None) # ignore close

win.iconbitmap('py-blue-trans-out.ico') # not red Tk

msg = Button(win, text=tree, command=win.destroy) # kills one win

msg.pack(expand=YES, fill=BOTH)

msg.config(padx=10, pady=10, bd=10, relief=RAISED)

msg.config(bg='black', fg=color, font=('times', 30, 'bold italic'))

root.title('Lumberjack demo')

Label(root, text='Main window', width=30).pack()

Button(root, text='Quit All', command=root.quit).pack() # kills all app

root.mainloop()

This program adds widgets to theTkroot window, immediately pops up threeToplevelwindows with attached buttons, and

uses special top-level protocols. When run, it generates the scene

captured in living black-and-white in

Figure 8-4

(the buttons’ text

shows up blue, green, and red on a color display).

Figure 8-4. Three Toplevel windows with configurations

There are a few operational details worth noticing here, all of

which are more obvious if you run this script on your machine:

- Intercepting closes:

protocol Because the

window manager close event has been intercepted by

this script using the top-level widgetprotocolmethod, pressing theXin the top-right corner doesn’t do

anything in the threeToplevelpop ups. The name stringWM_DELETE_WINDOWidentifies the close

operation. You can use this interface to disallow closes apart

from the widgets your script creates. The function created by this

script’slambda:Nonedoes

nothing but returnNone.- Killing one window (and its children):

destroy Pressing the big black buttons in any one of the three pop

ups kills that pop up only, because the pop up runs the widgetdestroymethod. The other

windows live on, much as you would expect of a pop-up dialog

window. Technically, this call destroys the subject widget and any

other widgets for which it is a parent. For windows, this includes

all their content. For simpler widgets, the widget is

erased.Because

Toplevelwindows have parents, too, their relationships might

matter on adestroy—destroying

a window, even the automatic or first-madeTkroot which is used as the default

parent, also destroys all its child windows. SinceTkroot windows

have no parents, they are unaffected by destroys of other windows.

Moreover, destroying the lastTkroot window remaining (or the onlyTkroot created) effectively

ends the program.Toplevelwindows, however, are always destroyed with their parents, and

their destruction doesn’t impact other windows to which they are

not ancestors. This makes them ideal for pop-up dialogs.

Technically, aToplevelcan be

a child of any type of widget and will be destroyed with it,

though they are usually children of an automatic or explicitTk.- Killing all windows:

quit To kill all the windows at

once and end the GUI application (really, its activemainloopcall), the root

window’s button runs thequitmethod instead. That is, pressing the root window’s button ends

the program. In general, thequitmethod immediately ends the entire

application and closes all its windows. It can be called through

any tkinter widget, not just through the top-level window; it’s

also available on frames, buttons, and so on. See the discussion

of thebindmethod and its

this chapter for more onquitanddestroy.- Window titles:

title As introduced in

Chapter 7

, top-level window

widgets (TkandToplevel) have atitlemethod that lets you change the

text displayed on the top border. Here, the window title text is

set to the string'Sing...'in

the pop-ups to override the default'tk'.- Window icons:

iconbitmap The

iconbitmapmethod

changes a top-level window’s icon. It accepts an

icon or bitmap file and uses it for the window’s icon graphic when

it is both minimized and open. On Windows, pass in the name of a

.ico

file (this example uses one in the

current directory); it will replace the default red “Tk” icon that

normally appears in the upper-lefthand corner of the window as

well as in the Windows taskbar. On other platforms, you may need

to use other icon file conventions if the icon calls in this book

won’t work for you (or simply comment-out the calls altogether if

they cause scripts to fail); icons tend to be a platform-specific

feature that is dependent upon the underlying window

manager.- Geometry management

Top-level windows are containers for other widgets, much

like a standaloneFrame. Unlike

frames, though, top-level window widgets are never themselves

packed (or gridded, or placed). To embed widgets, this script

passes its windows as parent arguments to label and button

constructors.It is also possible to

fetch the maximum window size (the physical screen

display size, as a [width, height] tuple) with themaxsize()method, as well as set the

initial size of a window with the top-levelgeometry("widthxheight+x+y")method. It is generally

easier and more user-friendly to let tkinter (or your users) work

out window size for you, but display size may be used for tasks

such as scaling images (see the discussion on PyPhoto in

Chapter 11

for an example).

In addition, top-level window widgets support other kinds of

protocols that we will utilize later on in this tour:

- State

The

iconifyandwithdrawtop-level

window object methods allow scripts to hide and

erase a window on the fly;deiconifyredraws a hidden or erased

window. Thestatemethod

queries or changes a window’s state; valid states passed in or

returned includeiconic,withdrawn,zoomed(full screen on Windows: usegeometryelsewhere), andnormal(large enough for window

content). The methodsliftandlowerraise and lower a window

with respect to its siblings (liftis the Tkraisecommand, but avoids a Python

reserved word). See the alarm scripts near the end of

Chapter 9

for usage.- Menus

Each top-level

window can have its own window menus too; both theTkand theToplevelwidgets have amenuoption used to associate a

horizontal menu bar of pull-down option lists. This menu bar looks

as it should on each platform on which your scripts are run. We’ll

explore menus early in

Chapter 9

.

Most top-level window-manager-related methods can also be named

with a “wm_” at the front; for instance,stateandprotocolcan also be calledwm_stateandwm_protocol.

Notice that the script in

Example 8-3

passes itsToplevelconstructor calls an explicit parent

widget—theTkroot window (that is,Toplevel(root)).Toplevels can be associated with a parent just

as other widgets can, even though they are not visually embedded in

their parents. I coded the script this way to avoid what seems like an

odd feature; if coded instead like this:

win = Toplevel() # new window

and if noTkroot yet exists,

this call actually generates a defaultTkroot window to serve as theToplevel’s parent, just like any other widget

call without a parent argument. The problem is that this makes the

position of the following line crucial:

root = Tk() # explicit root

If this line shows up above theToplevelcalls, it creates the single root

window as expected. But if you move this line below theToplevelcalls, tkinter creates a defaultTkroot window that is different from

the one created by the script’s explicitTkcall. You wind up with twoTkroots just as in

Example 8-4

. Move theTkcall below theToplevelcalls and rerun it to see what I

mean. You’ll get a fourth window that is completely empty! As a rule of

thumb, to avoid such oddities, make yourTkroot windows early on and make them

explicit.

All of the top-level protocol interfaces are available only on

top-level window widgets, but you can often access them by going through

other widgets’masterattributes—links to the widget parents. For example, to set the title of

a window in which a frame is contained, say something like this:

theframe.master.title('Spam demo') # master is the container window

Naturally, you should do so only if you’re sure that the frame

will be used in only one kind of window. General-purpose attachable

components coded as classes, for instance, should leave window property

settings to their client applications.

Top-level widgets have additional tools, some of which we may not

meet in this book. For instance, under Unix window managers, you can

also set the name used on the window’s icon (iconname). Because some icon options may be

useful when scripts run on Unix only, see other Tk and tkinter resources

for more details on this topic. For now, the next scheduled stop on this

tour explores one of the more common uses of top-level

windows.