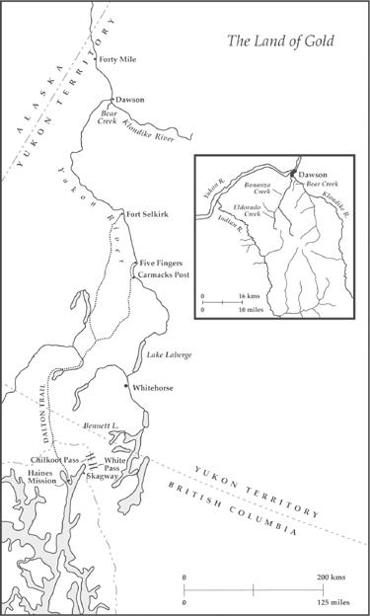

Prisoners of the North (6 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The industrial revolution in the gold country sparked by Boyle had changed the face of the Klondike, and there was no environmentalist movement to protest or prevent it. The low, rolling hills had long since been denuded in the growing hunger for lumber. The broad and verdant valleys were reduced to black scars by the big nozzles that tore at the topsoil and overburden to send the muck and silt coursing down to the big river. As the years rolled by, the dredges themselves, gouging out their own ponds, would reshape the rivers and creeks, leaving their own dung behind in the huge tailings piles of washed gravel that would choke the goldfields for more than forty miles.

Boyle’s monstrous dredge Canadian Number Four floating on its own pond and dipping into the bedrock for gold. The stacker is dumping gravel tailings at the stern

.

The irony is that, with the gold gone, the rape of the Klondike has become an asset. The tailings are now a tourist attraction; when some were bulldozed flat for a new housing development there was an outcry from those who saw them as part of the country’s history. Driving past this moonscape, goggle-eyed tourists are treated to another spectacle from the old days: Canadian Number Four, raised from the silt of the creek by the army, restored by Parks Canada, and officially designated an historic site, towers over its visitors on Bonanza Creek as a reminder of a romantic era and its Klondike King. There is no other monument to Joe Boyle in the land of gold.

But the king was growing restless. He had achieved everything he set out to do in the Yukon. His four great dredges were breaking all previous records; he had become a leading figure in Dawson, admired now as a local booster and praised for his philanthropy. On September 3, 1914, shortly after war was declared in Europe, he plunged into the fray in his characteristic Boyle fashion, offering to raise at his own expense a fifty-man machine-gun battery made up entirely of Yukoners. He also provided morning jobs for the new recruits in his company so that they could drill every afternoon. There were precedents for such grand gestures: the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry and the Lord Strathcona Horse had similar histories.

Speed was essential if Boyle was to get his men Outside before the ice made river traffic impossible. But even as they prepared to leave, Boyle had to acknowledge clouds gathering on his horizon. Hostilities had scarcely begun in Europe when Canadian Number Two, working the Klondike River, sank in some twenty feet of water. That meant the dredge would be out of operation for the best part of a year, eating up the profits as several score men tried to salvage the boat. As a result, gold production was cut by 20 percent or more. The dredge was raised at last the following July and placed on piles for inspection. Alas, it toppled from its makeshift perch, killing one man and injuring three others. Worse, three months later, on October 29, 1915, Boyle’s big steam generating and heating plant at Bear Creek, which serviced Dawson, burned to the ground.

War was another factor Boyle had not envisaged when building his big dredges. Operating costs had risen by $20,000 since 1913 while gold production values had fallen by the same amount. Dredging has some of the uncertainties of a Las Vegas roulette wheel. As the early stampeders had discovered, some claims were fabulously rich, others worthless. By this time Boyle’s dredges were working poorer ground—so poor that wages had to be postponed until better prospects showed up.

Until this point Boyle’s active life had been crowned with a series of successes, and he had reason to feel content. But now his career had begun to unravel, or so it must have seemed to him. In his pride he could not have foreseen that one of his mammoth machines might fail or a world war force up his costs and bring down his profits.

October 10, 1914, was a bittersweet benchmark in Boyle’s peripatetic career. That was the day when the recruits for his machine-gun battery would leave the Yukon for active service. And that was the very day on which Canadian Number Two sank in the Klondike. Boyle worked all day at Bear Creek to help save it. That evening he hurried to Dawson to bid his detachment farewell. In its spirited account of the unit’s departure, the

Dawson News

noted a silent man who stood at the edge of the barge with bared head as the steamer plowed past the shouting crowd and “watched the ship and her brave boys until she was out of hailing distance.” It was Boyle, who seemed “transfixed, gazing until only the dancing lights were visible on the water.” Then he quietly turned from his place and marched up the street with the crowd.

Boyle, ever the man of action, desperately wanted to be where the action was—not in Dawson, declining into a ghost town, but with his brave boys, far from the growing frustrations (financial, mechanical, and legal) that would continue to bedevil him. His brave boys, however, were not in Europe but languishing in Vancouver’s Hastings Park, transformed into a military camp, “a forlorn outfit,” in the words of Leonard Taylor, “with no spiritual home, condemned to hours of square bashing and route marching, dulling to the soul of Yukon individualists.”

Boyle put on the pressure, went over the heads of the army, and straight to the Minister of Militia, the choleric Sam Hughes. Finally he got his way: the unit was posted overseas in the summer of 1915. In England, Boyle’s frustrations increased when he attempted to have a Canadian put in charge of the battery and was told peremptorily that the machine-gun section was under the control of Imperial authorities. In the end the battery was broken up and its identity destroyed, shattering Boyle’s hopes for a close-knit band of Northern brothers, side by side, attacking the hated Hun.

The zest was going out of Boyle’s life. His ardour was dampened by the news that his old rival George Black, the Tory lawyer who had opposed him in his court battles, had been given leave to organize a Yukon infantry company to fight in France. Not only that, but Black was studying for a commission to lead his men in action. This must have galled Boyle, who was itching to get into service but at the age of forty-nine was not eligible. Black was forty-three.

In the Yukon, Boyle would remain a controversial (if engaging) figure long after his death. Andrew Baird, a friend of my family and a regular guest at our dinner table during my Dawson days, wrote in his memoirs that the story of Boyle’s activities in the Klondike was more like a fairy tale than a factual record. “He wrecked his company with ill-conceived policies and left it in a hopeless muddle,” he wrote. Baird of course was not unbiased, being associated with A. C. N. Treadgold and the rival Yukon Gold Corporation.

When Flora Boyle told her

Maclean’s

readers that her father “could not endure to be bound,” one suspects that she was referring to more than his unfortunate marriage. Boyle was tied to his faltering company and confined to the far-off Yukon at a time when others were flocking to their king’s aid in the poppy-dotted fields of Flanders.

It was too much. The man who had solved his daughter’s problems with her stepmother by pushing her off to distant climes now chose another form of escape. Like a small boy who picks up his marbles sobbing “I don’t want to play any more,” Joe Boyle slipped quietly out of town in mid-July 1916, leaving the Klondike behind forever.

The Boyle contingent of Yukon machine-gunners at their barracks in Dawson City

.

This was a surprising decision and, given Boyle’s long history of success in the Klondike, a remarkable one. He was not a man to let sudden setbacks deter him. Or was he? There is an adolescent quality to Boyle’s unexpected flight from reality, for that is what it was. Certainly, wartime conditions had made his business affairs more difficult. It was hard to get the supplies, the equipment, and the men he needed to keep the company alive. Dawson was slowly dwindling, and so was the supply of gold. But surely this was not the time to abandon the mining empire that had been his pride. What was needed was a firm hand on the tiller. For Boyle at this juncture to turn the whole enterprise over to his son Joe was akin to a dereliction of duty. If the senior Boyle had stayed on the job, could he have saved his ailing business? The answer is that fifty years later, after others reorganized and consolidated the company, the great Boyle dredges were still working the famous creeks and still producing gold.

For Boyle, the fun had gone out of the mining business. The real “fun” lay elsewhere, in the battlefields of France. Boyle wanted to escape the burdens of the Klondike. He wanted to be known as Klondike Boyle, and for the rest of his life he was, but he wanted the glamour without the responsibilities. The outside world, of course, from Ottawa to Odessa, did not know that in the Klondike he was a failure.

Now, in the twenty-first century, it is hard for us to comprehend the mindset of the Great War generation, when the soldiers and the generals, too, were idolized as lily-white heroes and a man out of uniform, even a middle-aged man, was seen as a slacker. The propaganda that sold the war as Great Adventure was designed to recruit young men—the flower of the nation—and send them willingly, even joyously, into the trenches of Flanders: to make them feel themselves noble crusaders for their country doing battle with the Antichrist. No one in Boyle’s generation would ever censure him for abandoning his business enterprise in order to save civilization.

When Boyle left Canada for London, he took a piece of the Yukon with him. That was a purposeful decision. He could run away from all the frustrations and unexpected financial problems that had been visited upon him, but he could not escape the aura of the golden North that attended him—nor did he want to. In London, his circle of acquaintances, carefully cultivated during his earlier trips, grew wider. “Klondike” had become a word in the language that connoted glamour, adventure, heroism, and sudden wealth. Now he was Klondike Boyle, a title worth more, in some circles, than a knighthood because it was unique. At the level in which he moved he was not seen as a lone prospector who had stumbled upon a paystreak; he was the King of the Klondike. It was for Boyle a kind of brand name providing a conversational gambit that gave him easier access to military, business, and social circles that might otherwise have been closed to him. He had left the North but the North had not left him. In that sense, he would always be its captive.

Now Boyle’s contribution to the war effort in the form of a machine-gun battery, costly as it was, began to pay off. On September 16, 1916, he was gazetted an honorary lieutenant colonel in the Canadian militia. It gave him a title and a touch of authority. But it also burdened him with a reputation. He spent the rest of his life subconsciously living up to it—the bold sourdough and entrepreneur who feared nothing and dared everything. Fortunately, he had the stamina, the will, and the zest to press forward against all odds.

He did his best to wipe out the intimacies of his past. Save for one letter, Elma Louise never heard from him again although she made repeated attempts to seek him out. Nor was his son, Joe, who took over active management of the company, able to reach him once he had plunged into new adventures. Again it was out of sight, out of mind, which helps explain the indifference that young Joe, burdened now by the responsibilities his father had saddled him with, exhibited in Boyle’s last days.