Prisoners of the North (7 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The rank had no military significance. The army doled out many honorary commissions to prominent citizens who had helped the war effort. Boyle was little more than a civilian in costume, but he made much of it. He lost little time in switching to a well-tailored uniform of officer’s serge complete with Sam Browne belt. Now he was “Colonel Boyle” also, and he revelled in the title, which was to become useful to him in eastern Europe. Few would realize that he was not a regular officer. He was never seen in mufti but made a point of wearing his uniform at all times, complete with the word yukon in large black letters stitched on his shoulder straps. He went further: on each lapel, a Canadian maple leaf gleamed with unaccustomed brilliance. These caused considerable comment because they needed no polishing, being fashioned of genuine Klondike gold—a regimental quiff for a man without a regiment.

It is tempting to think of Joe Boyle in cinematic terms. We can almost see the word finis on the screen as he boards the steamboat and fades into the distance. He has dispensed with his own past and we can only wait for the movie sequel: king of the klondike Part 2, subtitled

The Saviour of Romania

, which, unlike most sequels, manages to surpass the original.

In London, the man of action wanted, once again, to be where the action was—if not in the front lines, at least serving his country as part of the war effort. Boyle’s own pride was involved. How could he, a powerful man of forty-nine, be cast aside like a used topcoat? Other men of his age were being shamed as slackers by aggressive young women who taunted them with white feathers. Boyle’s uniform protected him from that, but there is little doubt he himself felt he was not pulling his weight. He lobbied intensely, using his social connections (Herbert Hoover was one), to try to get into the fight. That didn’t happen until the United States entered the war and the Russian czar, Nicholas II, abdicated. The American Society of Engineers was formed that spring to help support wartime Washington, and Boyle knew the honorary chairman, who had shown an interest in his dredging operations. One connection led to another, and on June 17, 1917, Boyle, who spoke no word of Russian, went off to Russia on the recommendation of another American friend, Walter Hines Page, U.S. ambassador to Great Britain, ostensibly to help reorganize the Russian railway system. He knew very little about railways, but he certainly knew a good deal about organization, and that turned out to be exactly what was needed.

—THREE—

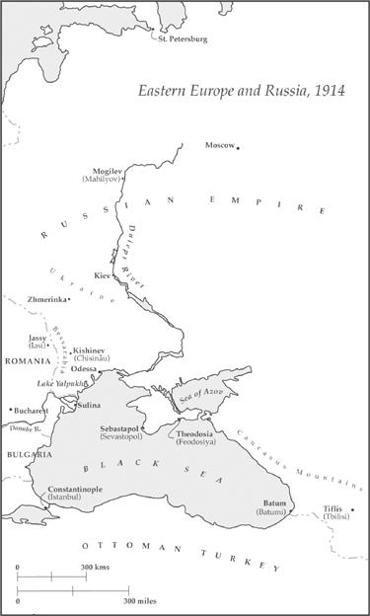

When Boyle arrived in Petrograd (St. Petersburg, then capital of Russia) in July 1917, eastern Europe was in chaos. The provisional Lvov–Kerensky government, which had replaced the old czarist regime, was clinging to power, shored up by the Allies who needed to keep Russia active in the war in the face of Bolshevik insurgents. Boyle made contact with the Russian military authorities who accepted his services, though with some hesitation, while the British War Office was trying not very successfully to find out what he was doing and under what authority.

Boyle soon moved southwest to Romania to try to assess the stalemate caused by the tangle in the Russian and Romanian transportation systems. Romania had declared war on the German-led Central Powers in August 1916, but her railways were in such a state of disorder—half-finished in some cases, ending abruptly in others—that it was impossible to ensure a steady stream of supplies to the troops of either country.

Boyle got the system working by making use of Lake Yalpukh (now in Ukraine). This was a long finger of water running north from the Danube River near its delta. He saw that one end of an existing rail line could be extended to the southern tip of the lake where ships could be used to replace the gap in the rails. The link to the railhead at the northern shore thus formed unravelled the transportation snarl.

Here the new movie begins, with a montage of overlapping shots showing Boyle in action in the no man’s land of the post-revolutionary Eastern Front. There is a fictional quality to these tales of Boyle’s adventures in eastern Europe—the kind of stories that English schoolboys thrived on through the pages of the

Boy’s Own Paper

. They come to us not through Boyle, who tended to shrug off his own exploits, but from a reputable eyewitness, Captain G. A. “Podge” Hill, the British intelligence officer who was from time to time Boyle’s comrade-in-arms. Indeed, Hill himself later confessed that he had played down Boyle’s role in some dauntless deeds in his memoirs to build up his own part in them. If Boyle’s new adventures seem to have the earmarks of a Saturday matinee movie serial—and they do—they are not the less impressive because they are true.

The southeastern sector of Europe at this point was in turmoil. Romania had been torn in half by the advance of the Central Powers. The provincial town of Jassy (Iasi) had replaced Bucharest as its temporary capital. The Russian army was disintegrating and the provisional government was tottering.

Boyle was in the thick of it, as Hill’s memoirs,

Go Spy the Land

, make clear. He records one incident where Boyle prevented a near riot in the provincial town of Mogilev on the Dnieper (now in Belarus). Feeling was running high at the presence of the Allied Military Missions to Russia, which were doing their best to counter German-Austrian propaganda among members of the newly formed Soldiers’, Sailors’, and Peasants’ Council. A meeting of the council was agitating to have the missions expelled or their members murdered. In the midst of this hullabaloo, Boyle strode onto the stage of the assembly and started to speak, with Hill translating. There was a movement to rush the stage, but Boyle’s voice, “clear and musical,” to quote Hill, held the audience. In a short speech, full of references to Russian history, Boyle reminded his listeners that Russians had never surrendered. “You are men, not sheep!” he told them. “I order you to act as men!” Thunderous applause followed as one young Russian leaped on the stage and cried, “Down with the Germans!” That ended the anti-Allies uproar.

A stranger who didn’t speak a word of the language walking onto the platform and subduing an angry mob! It strains credulity. But Hill was there, on the stage with Boyle, translating his words sentence by sentence as he uttered them. As so often in the Boyle story, fact again outdid fiction.

At the request of the Romanian government through its consul general in Moscow, Boyle undertook a special mission. Some twenty tons of paper, including diplomatic documents and all the currency that the beleaguered Romanians had had printed on Moscow presses, were in peril. Because the Russians were impressed by Boyle’s work on organizing the Romanian railway system, he and Hill were able to secure a private carriage and the rolling stock they needed to pack four cars with the Romanian papers. They hooked these up to an overcrowded southbound train and set off for the harassed country nearly a thousand miles to the southwest. The journey was fraught with danger, for the route lay directly through territory over which the Bolsheviks and the Russians were contesting.

Boyle and Hill were running the gauntlet through a land in ferment. When undisciplined Bolsheviks tried to uncouple the cars at a small railway station, Boyle crept out under cover of darkness and knocked the leader cold. On the way to Kiev, the train stopped dead for lack of fuel, and Boyle organized a human chain of passengers to bring back logs from a nearby clearing in the forest. With some men up to their armpits in the soft snow, the logs were passed back to the stranded locomotive until the tender was piled high. The engineer finally got up steam and they reached Kiev, where they were able to attach their cars to another train.

At Zhmerinka, forty miles from the then Romanian border, a Bolshevik officer stopped the train, shunted the rescuers’ cars onto a siding, and trained a gun battery on the station to prevent any escape. Boyle’s response was to throw a party and an impromptu concert for the Bolshevik soldiers to show his lack of concern and to conceal his next scheme. Fortunately, in the yard an engine stood in constant readiness for shunting purposes. Hill and Boyle boarded it and forced the engineer and stoker at gunpoint to pick up the cars carrying the Romanian treasures. After Boyle cut both the telephone and the telegraph wires, the train with the pair aboard set off at top speed. Twenty minutes later they reached a level crossing barred by a gate. When the engineer refused to crash through, they kneed him to the floor. Seizing the throttle, Hill opened it to full speed and “the good old shunting engine carried everything before it in its stride.” When they finally reached Jassy, they were met by an escort of 250 Romanian railway gendarmes and a body of Romanian army cavalry to secure the country’s vital papers. It was Christmas Eve, 1917—a bright moment in an otherwise dark year.

Boyle was in Petrograd when the Kerensky government fell and the Bolsheviks took over. Six days of street fighting prevented any trains from leaving the capital, and Moscow was starving. The untried Bolshevik regime was forced by circumstances to release the former minister of war, General Alexei Manikovskii, from prison with orders to feed the army. Manikovskii sent for Boyle, who had just been made chairman of the All-Russia Food Board, and asked him to go to Moscow to untie the railways knot and get supplies moving.

Boyle’s methods were unorthodox, but they worked. By pitching entire trains over embankments and pushing empty cars into the fields, he eliminated the bottleneck in three days, and the Russian armies on the Eastern Front were saved from starvation.

Both Russia and Romania had signed armistices with the Central Powers that December, and the Germans were moving in to occupy the country. Boyle now turned his attention to averting a war between the Russian Bolsheviks and Romanian forces. After weeks of hard negotiations with the Germans at the very gates of the capital, Boyle, shuttling by light plane between Jassy and Odessa (and once nearly brought down by a Romanian anti-aircraft battery), finally got his way. An agreement between the Russians and Romanians brought an end to hostilities in late February 1918 and was followed in May by a peace treaty between Romania and the Central Powers signed at Bucharest.

In effect, Boyle was acting as an unofficial and unaccredited agent, as William Rodney has noted and as Hill well knew. Boyle had contacts among high-ranking Soviet officials as well as some senior Allied representatives; moreover, he could move freely about the country, unlike the Allied ambassadors and ministers who were cooped up in Petrograd and cut off from what was going on in Russia because their governments had not yet recognized the new regime.

Early in January 1918, for example, an important and dangerous plan was worked out by the commander of the French mission to Romania in which Boyle would use the authority he had been given by the Bolsheviks “to drift locomotives from the North to South Russia and create as much disorder and confusion in the Railways Systems in the North as possible”: in short, an act of sabotage. In that same period the Romanian prime minister, Ion Brătianu, asked Boyle to go to Petrograd on his behalf on a delicate mission to assure Leon Trotsky, then Bolshevik commissar for foreign affairs, that the Jassy government wanted to avoid friction between Romania and the new Soviet regime.

Motion pictures, like stage plays, tend to be divided into three acts. The first act of

The Saviour of Romania

was now complete. Since every good movie requires a love interest, the second begins in March 1918, when Boyle meets Marie, the alluring Queen of Romania.

She was Queen Victoria’s granddaughter, tall, elegant, spirited, intelligent, and still beautiful at forty-three—everything, in short, that a queen should be. It was she who had stiffened the spine of her Hohenzollern husband, the weak and vacillating King Ferdinand, persuading him to put his natural inclinations aside and join the Allies in their war against the Germans and the Central Powers.

She was a romantic in the grand sense. At the moment of her greatest despair, the arrival of a bold and unconventional Yukoner gave her courage. At their first brief meeting on March 2, she had only the vaguest idea of who he was, but he was certainly impressive. “A very curious, fascinating sort of man, who is frightened of nothing, and who, by his extraordinary force of will, gets through everywhere. The real type English adventurer books are written around.”

The second meeting lasted two hours, with the Queen at her lowest ebb. The Allied missions were vacating Jassy, fearing the German advance would cut them off, and the Queen stayed up to make her farewells. It was a black night, the rain pouring down as if to accentuate her anguish. Then, into the reception hall, uniform dripping from the deluge, walked Joe Boyle. “Have you come to see me?” she asked as he advanced to meet her. “No, Ma’am,” Boyle replied, “I have come to help you.”