Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (36 page)

That situation is changing, however. John Weaver, a research biologist with the Wildlife Conservation Society, has developed an excellent tool for assessing lynx numbers. After watching his captive lynx rub her cheeks against a post, Weaver devised rubbing pads with nails protruding from them. Treated with his secret formula, which includes catnip, and scattered about in lynx country, these pads collect hairs from the big-footed cats, which seem to enjoy rubbing against them. For example, in Montana’s Kootenai National Forest, twenty-eight rubbing pads yielded lynx hairs. The trick, of course, is in determining how many different lynx are represented by these samples. Fortunately, DNA analysis has come to the rescue.

Utilizing cats in its research, the National Cancer Institute has done considerable work on leukemia. In 1995, Stephen O’Brien, performing studies at the Institute, refined a basic DNA analysis so that it became useful in testing lynx hairs. This test is currently being used by the Wildlife Conservation Society to analyze lynx hair samples from the Kootenai Forest and several other locations in Canada and the United States. Preliminary results indicate that several different lynx deposited the twenty-eight hair samples from the Kootenai, but additional analysis is required to determine the minimum number of individuals represented by the samples.

It’s estimated that there are several hundred lynx in the lower forty-eight states, but these are often in isolated populations, beleaguered by destruction or fragmentation of their habitat. With pressures of this sort increasing, concerned scientists and conservation organizations have pressed the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the lynx as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. The Service has so far declined, citing its limited resources and the need for further lynx studies.

However, biologists with the Colorado Division of Wildlife have released thirty-seven lynx imported from Canada and Alaska. If enough of these survive, the biologists hope to release fifty more of the cats next year. If successful, this would be a major step toward returning the lynx to some of its former range.

Farther north, the lynx is in much better shape, and is thought to be holding its own. Although their numbers fluctuate widely according to hare cycles, there are believed to be at least tens of thousands of lynx in Canada and Alaska.

The life of a bobcat is very different from that of the lynx, close cousins or not. Life in the wild is never easy, but bobcats mostly reside where the climate is far less forbidding than that which confronts the lynx. Indeed, the ranges of the two species scarcely overlap: the bobcat, which roams down through Mexico, barely spills over into southern Canada, while the lynx inhabits only a tiny chunk of the United States, exclusive of Alaska. This rather neat geographic division has its advantages for the lynx: throughout most of its range, it has no competition from the more aggressive bobcat.

With bitter cold and deep snows less of a problem, the bobcat has evolved in a very different manner from its boreal cousin. It features smaller feet, much shorter legs, a more compact frame, and an altogether more typically catlike appearance than the lynx. Its coat, while ample for winter protection in the northern parts of its range, falls far short of the lynx’s incredibly thick, luxurious pelt. Even the bobcat’s markings are more catlike; its pronounced facial patterns closely resemble those of the tiger tabby model of the house cat, as well as those of a number of the world’s small-to-medium wild cats.

If the lynx is a specialist, bound by evolution to the snowshoe hare, the bobcat is a supreme generalist. Rabbits, hares, mice, voles, squirrels, grouse, small birds, birds’ eggs, snakes, frogs, crustaceans, and dead—though not rotting—animals are all grist for the bobcat’s mill. Although some of its prey are cyclical, the bobcat has a wide array of alternative sources to keep it fed.

Only in severe winters in the northern extension of its range is food likely to be a serious problem for the bobcat, whereupon it often turns to the carcasses of dead deer to carry it through. Bobcats are also known to kill deer during particularly harsh winters. Small deer, less than a year old, are usually its victims, but sometimes older deer are also killed, usually by very large male bobcats. Despite these occasional depredations, the bobcat doesn’t rate as an important predator of deer.

Even more than its lynx cousin, the bobcat is a stalker and pouncer. A bobcat may sprint after prey for short distances if the effort seems warranted, but that’s not its usual hunting technique. Bobcats are noted for their slow, cautious stalking, and one will sometimes remain for considerable periods beside a burrow, waiting for its unsuspecting prey to emerge.

A friend of mine, Paul Kress, witnessed an amazing demonstration of a bobcat’s slow, patient stalking technique, as well as its uncanny ability to pinpoint the location of a fairly distant sound. Turkey hunting in Massachusetts, Paul was seated on a log, dressed in camouflage clothing, using a turkey call from time to time.

A movement caught his eye, and he was astonished to see a bobcat creeping ever so cautiously in his direction. Paul froze, keeping absolutely still in order to avoid alerting the bobcat. On came the bobcat, step by slow step, until it actually started up the log on which Paul was sitting.

At that point the cat seemed to sense that something wasn’t exactly as it should be, although it seemed unsure why. It halted, then very slowly backed away before gradually melting into the forest. Even though Paul had stopped calling as soon as he saw the bobcat, the cat seemed to know the precise spot from which the supposed turkey calls had emanated!

Because they feed on such a wide array of creatures, bobcats are far less demanding than lynx in their habitat requirements. Everything from large, wild tracts of northern forest to farm country to scorching desert serves as home for this versatile cat. No doubt this versatility accounts, at least in part, for the bobcat’s relative abundance. Estimates of North America’s bobcat population vary widely, but even the lowest are nearly three-quarters of a million, while the high estimates are double that.

The preferred denning sites for bobcats are crevices in rocks or ledges, wherever these are available, but hollow logs, pockets beneath blown-down trees, and similar places also serve very well. In usual cat fashion, bobcat kittens are born with their eyes closed. The average litter size is two, but sometimes there are as many as four. Like the lynx and other cats, the kittens open their eyes after about ten days, and begin to forage with their mother after a few weeks. The kittens sometimes leave their mother in the fall, but may also remain with her through the winter. In the southern portions of its range, the bobcat may have two litters a year.

Both bobcat and lynx are wary, elusive, and seldom seen. This trait is much more evident in the bobcat, however, because it frequents far more settled country than the lynx usually inhabits. The bobcat’s mainly nocturnal ways add to the difficulty of seeing one, and many people who have spent much time in the woods for years have never laid eyes on a single bobcat. Thus I count myself as extraordinarily fortunate to have had one memorable encounter with this elusive feline.

It was Thanksgiving Day, 1971. I was deer hunting, perched in a tree overlooking an old field that had grown up to tall grass and, here and there, scrubby little bushes. It was over two hundred yards to the woods at the lower edge of the field, and one of my hunting partners was ensconced another hundred yards or so down in the trees, over a steep bank.

The ground was still bare, but the lowering sky was a dark, forbidding gray as the first few flakes of snow began to fall. As I looked toward the bottom of the field, I caught a brief sight of a smallish, stocky animal. At that distance it resembled a squat little dog, and the thought crossed my mind that someone’s Scottie might be running loose. Then the snow began to descend in earnest, and I completely forgot about the animal. Faster and faster came the whirling flakes, and in an hour or so there were a number of inches of snow on the ground, while every little shrub and tussock was draped in a thick mantle of white.

Only twenty or thirty yards below me was a path where my hunting partner had trampled the long grass on his daily trips to his chosen hunting spot. Without warning or any prior hint of movement, a bobcat materialized in the path and stood there, almost facing me. I was stunned by its sudden appearance, but had presence of mind enough to raise my rifle and view the cat through the scope.

Several thoughts ran through my mind as the scope revealed the cat in wondrous detail. The first was what a beautiful animal it was. The second was that its bold facial markings were almost identical to those of our two gray tiger tabbies. The third was that it was one very cross-looking cat, seemingly at odds with the whole world! I marveled at the sight—and then, as if without motion, the cat dematerialized as mysteriously as it had appeared.

Some time later I made out the form of my hunting partner, trudging uphill through the swiftly deepening snow. I hurried down to meet him, and excitedly asked, “Guess what I saw, Art?”

“A bobcat,” he replied.

“How did you know?”

“Well,” he informed me, “just as it was starting to snow, I heard a noise in the leaves up the bank from me. I turned, and there were a mother bobcat and three kittens that were about three-quarters grown. They saw me and scattered in all directions.”

It was the mother that I had seen, of course; the kittens had evidently stayed in the woods below me and hadn’t come into the field with their mother. Probably the reason why the cat looked so cross was that she and the kittens had been temporarily separated, though they no doubt found each other soon after. Incidentally, we got twenty-two inches of snow that day, making it my most memorable Thanksgiving in more ways than one!

Our younger son also saw a bobcat, but under very different circumstances. As he was driving through a wooded area, a bobcat raced out of the snow-covered evergreens into the path of the car ahead of him. Dave immediately stopped to check on the cat, which was unfortunately dead. It was unmarked, however, as it had apparently been struck in the head, but not run over. It was a beautiful specimen, so Dave took it to the Vermont Institute of Natural Science, where, the last I knew, it was preserved in their freezer.

Then there was the very strange experience of an acquaintance, who lives on the fringe of Montpelier, Vermont’s capital city. He looked up from his yard work to see a doe walking down the street, followed at a discreet distance by a fairly small bobcat! Why the bobcat was acting in that fashion is something of a mystery. Certainly it wasn’t about to attack a full-grown deer in warm weather. Quite possibly it was a kitten, almost grown and just setting out on its own, either testing its stalking skills or simply following the much larger animal out of sheer curiosity.

Both bobcat and lynx can be quite vocal at times, although they don’t make a habit of it. The bobcat’s voice is often described as sounding very much like that of an oversized house cat, with loud yowling, growling, hissing, and spitting. Certainly my only experience with a bobcat’s voice reinforces that description.

One frosty autumn morning while I was in high school, I arose at first light to do a little hunting before school. I was crossing the field behind our house, when from the nearby woods came loud noises that sounded for all the world like a solo version of a fight between house cats, only louder. Although I suspected the source, I wasn’t sure until a neighbor who was an old woodsman, hunter, and trapper emerged from the woods.

I hurried over to him and asked, “Did you hear that noise? What was it?”

“Bobcat,” was his succinct reply.

Over the years, however, I’ve encountered a number of people who have recounted how frightened they were, almost always at night, by “a bobcat’s scream,” which they generally described as “bloodcurdling” and “sounding like a woman who’s being murdered.” This simply doesn’t seem to fit with what’s known about the bobcat’s vocal repertoire: perhaps it’s possible to interpret the sort of

raowraowraowraow

yowls, such as fighting tomcats unleash on each other, as bloodcurdling screams, but this seems a bit farfetched. The likeliest explanation is that the high-pitched scream uttered by none other than our old friend the barred owl (see page 110) is frequently attributed to the bobcat.

Bobcat populations generally seem to be holding their own, and may even be increasing. Indeed, this versatile feline is full of surprises: despite its generally reclusive nature, bobcats of late have been adapting to life in the outskirts and suburbs of a number of cities. Although they still tend to avoid being seen during daylight hours, or walking where they’re readily visible, bobcats have apparently adjusted to the proximity of large numbers of people. Such adaptability, of course, bodes well for the future of this handsome feline.

While there’s justifiable concern about the future of the lynx in the southern extremities of its range, the big-footed cat appears to be doing well in Canada and Alaska. Although its cyclical nature makes population trends difficult to determine, it seems likely that the lynx, together with its bobcat cousin, will continue to intrigue and delight all those who find the wondrous abilities of cats so fascinating.

20

The Magnificent One: The Cougar

MYTHS

The cougar is an endangered species.

The cougar is an endangered species.

Cougars are no threat to people.

Cougars are no threat to people.

THE COUGAR

(PUMA CONCOLOR)

MIGHT WELL BE DUBBED THE CAT OF MANY NAMES. Mountain lion, puma, catamount, panther, and painter are among the most common, but numerous other English, Spanish, and Native American titles have been applied to this big cat. The sources of these names are as varied and curious as the names themselves.

Mountain lion

is self-explanatory, but

puma

comes through Spanish from a Peruvian word.

Panther

entered the English language from the Old French

pantere,

which in turn goes back through Latin

panthera

to the Greek

panther. Painter

is simply a colloquial pronunciation of panther, and

catamount

is a form of

cat o’mountain.

And

cougar,

my personal preference, is French, taken from the language of the Tupi Indians of South America.

“What’s in a name?” Shakespeare wrote. “That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” and this gorgeous great predator is just as splendid whether we call it cougar, puma, mountain lion, panther, or some other name. This is by far the largest cat commonly found in North America above the U.S.–Mexican border; although the jaguar is slightly heavier, it rarely reaches the U.S. side.

The cougar’s scientific name,

Puma concolor,

means a puma of the same— or one—color (until recently, the name was

Felis concolor—

cat of one color). At any rate, the species name is an apt description of this big feline’s basic appearance. Most of the cougar’s coat is tawny, reminiscent of the African lion’s color, but the underparts are much lighter, and the tip of the tail and backs of the ears are dark brown to nearly black.

Cougar

Much of the cougar’s arresting beauty stems from its opposite ends—its face and tail. Viewed face on, the cougar’s tan head culminates in a strikingly handsome pattern: its pink nose is surrounded by a white muzzle, set off by vertical blackish bars at the rear. At the other end, the cougar’s tail is perhaps its chief glory. Nearly three feet long on really large specimens, this appendage, when adorned by the cougar’s winter fur, is truly majestic. Indeed, in its thick winter pelage, the cougar fully deserves to be called magnificent.

Just how large are cougars? The heaviest recorded specimen, a male, weighed a whopping 275 pounds, but that’s an obvious anomaly. Other male cougars, which are substantially heavier than females, have occasionally reached 225 to 230 pounds, but John Beecham, a cougar expert with the Idaho Fish and Game Department, says it’s extremely rare to encounter a male over 200 pounds; 130 to 150 pounds is more typical for adult males, while females tend to weigh seventy-five to ninety pounds.

As for length, big males can run seven to eight feet from nose to tip of tail. In one study, adult males averaged just over seven feet in total length, females about six and a quarter feet. The cougar’s splendid tail accounts for between 35 and 40 percent of that total, although it often appears longer.

For reasons that aren’t entirely clear, there seems to be a pervasive feeling that cougars as a species are—depending on whose opinion one listens to—either rare, threatened, or endangered. Perhaps this is due to the publicity given to the Florida panther

(Puma concolor coryi),

a cougar subspecies that is genuinely endangered; after all, the image of a Florida panther on a poster or an endangered-species stamp looks very much like any other cougar. Also, the fact that cougars are listed as endangered in the eastern United States may lead people to think that the species overall is in deep trouble.

In truth, cougar populations in the western states and parts of western Canada have increased greatly in the past couple of decades and seem to be thriving. But how many cougars are there? Unfortunately, that’s a very difficult question to answer. Counting cats, it turns out, is only slightly easier than the proverbial task of herding them!

Like most wild cats, cougars are highly secretive. Further, many of them live in the remote vastness of wilderness areas. This makes any accurate assessment of their numbers a daunting task. Nonetheless, based on the best estimates possible under the circumstances, biologists have come up with a total figure of 25,000 to 30,000 cougars in the United States and Canada. (These figures should be viewed in light of the biologists’ caveat that they are

very

rough estimates.)

Cougar numbers in the East (excluding Florida) are another matter. Cougars were long ago eliminated from the East, but have they returned to their old haunts? Many people think so. Although the idea of a thriving eastern cougar population is at best highly speculative, it’s nonetheless hotly debated. Reports of cougar sightings are rife in the northeastern states, and several organizations exist exclusively to promote the belief that thousands of cougars roam the forests there.

Biologists point to the almost total lack of any hard evidence that these great cats are present as a breeding population in the Northeast. They believe that most cougar sightings are cases of mistaken identity, and those that are genuine are mostly “pet” cougars released into the wild.

It’s an unfortunate fact that cougar kittens can easily be purchased from animal farms in some states. Emotion overcomes some people when they view these undeniably adorable kittens and fail to foresee the day when their call of, “Here kitty, kitty, kitty,” is answered by a cat weighing one hundred pounds or more! Ultimately, owners who don’t know what else to do with such a large and potentially dangerous cat simply take it to a tract of forest land and release it. The tragedy is that cougars raised by humans almost certainly lack the hunting skills to survive for long in the wild.

True believers scoff at the notion that most alleged sightings are cases of mistaken identity, or that valid sightings are of “pet” cougars released into the wild. Further, they accuse wildlife biologists of conspiring to hide the truth because they don’t want an endangered species on their hands.

This view is both unfair and farfetched. Most biologists are fascinated by the big cats and would welcome the opportunity to study them firsthand. Further, it seems highly improbable that large numbers of cougars could inhabit the area without leaving tangible evidence of their presence, such as tracks, droppings, and deer kills. Cougars are certainly secretive and tend to keep out of sight, yet the endangered and seldom seen Florida panther—of which only thirty to fifty remain—leaves ample evidence of its existence.

Among other things, road-killed cougars are by no means unusual where cougars are known to exist. There are at least sixteen documented road kills of the endangered Florida panther in the last two decades, yet not a single road-killed cougar has been reported elsewhere in the eastern United States.

Another puzzling phenomenon is that a high percentage of supposed cougar sightings are reported as “black panthers.” The true black panther is a melanistic phase of the leopard, but there has never been a single documented case of a melanistic cougar anywhere. However, in the minds of a substantial portion of the public, the term “black panther” is firmly rooted, and so many black animals of various sorts are reported as cougars, alias black panthers.

This brings us to the amusing and highly instructive tale of a “black panther” that recently caused a furor in Vermont. A nurse leaving a nursing home saw what she believed was a black panther. She grabbed her camera and snapped several pictures, which she then took to the Fish and Wildlife Department. Department personnel visited the site and tried to estimate the size of what was clearly a black cat, based on the size of background objects. Their conclusion was that—in addition to being black—the cat was too small to be a cougar, but that it might conceivably weigh forty pounds and be the melanistic phase of some smaller species of cat released into the wild. Photos of the cat appeared in major newspapers, and the whole affair became the talk of much of the state.

Three or four days later, a lady who lived close to the nursing home took Porgy, her black male house cat, to the veterinarian for a routine checkup. The veterinarian, who had seen the newspaper photos, looked at Porgy, then said to the woman, “Don’t you think you’d better ’fess up?” She admitted that she ought to, but had been reluctant to do so because of all the publicity. She then contacted the Fish and Wildlife Department and told them that the photos were indeed of her wandering tom, who weighed less than twenty pounds, identifiable from the photos by a small white spot on his throat. Thus did a house cat named Porgy become a media star and “panther for a day”!

Erroneous reports of cougar sightings are by no means confined to the East. Cougar research biologist Paul Beier, who works in southern California, estimates that at least 75 percent, and perhaps as many as 95 percent, of reported cougar sightings are cases of mistaken identity. An astonishing range of animals, from domestic dogs and coyotes to bobcats and deer, are erroneously identified as cougars, and even experienced observers have fallen into this trap.

To date, only two cougar sightings—one in Maine and one in Vermont— have been validated (the one in Vermont by DNA testing of a hair sample). There has been no further evidence of these cougars, and it must be presumed that they were released specimens that have since perished. Beyond that, there is not a single piece of confirmed evidence that cougars exist in the East. If a breeding population were truly present in the East, it’s difficult to imagine that not a single cougar would have been struck by a car, or that no one would find deer killed by cougars, identifiable tracks, or other firm evidence of the cat’s presence.

The term “magnificent” applies not only to the cougar’s appearance, but to its physical prowess as well. In addition to its beautiful appearance, the cougar possesses that innate grace which seems to be nature’s gift to the cat family. Coupled with extraordinary power and explosive speed in a short sprint, this makes the big cat a marvelous killing machine that can dispatch prey many times its size. For instance, a 150-pound cougar can quickly kill an elk weighing up to one thousand pounds.

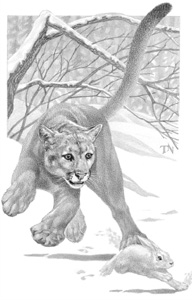

Like most other cats, the cougar isn’t a pursuit animal. In typical cat fashion, its usual mode of attack is to stalk its prey until it comes within striking distance. Then, with an amazing blend of speed and power, the cat overtakes its prey, leaps upon it, and delivers a killing bite to the neck, often at the base of the skull. That, at least, is what happens in the course of a successful attack; as with other predators of large animals, the cougar’s attacks fail more often than not, though that hard reality in no way diminishes the cougar’s exceptional skill as a hunter.

There are many ways in which even the cougar’s lightning attacks can go awry. Large prey—deer, elk, bighorn sheep, and the like—are extremely wary. No matter how careful the stalk, the slightest hint of movement will alert the prey and perhaps launch it into full flight. An errant puff of wind may carry the cat’s scent to the supersensitive nostrils of its intended dinner, or a tiny noise made by those soft, padded feet can sound the alarm.