Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (37 page)

Even if the cougar successfully moves into position to commence an attack, many things can still go wrong. The cougar depends upon a swift end to its onslaught, and the prey may be able, for example, to dodge the racing predator and accelerate to the point where the cat gives up the chase. At other times the prey may have sufficient warning to simply be able to outrun its pursuer. Predation, even by a cougar, is far from a sure thing.

Big game—deer, elk, and bighorn sheep—are the mainstays of the cougar’s diet; it’s also known to kill moose, though usually calves rather than adults. The big cat rounds out its diet with substantial numbers of smaller mammals such as hares, rabbits, grouse, coyotes, foxes, badgers, skunks, opossums, and raccoons. As previously noted, cougars are one of the very few animals able to kill an adult beaver (see chapter 5), which finds its way into the big cat’s diet from time to time. Small rodents, including ground squirrels and even mice, are also consumed, and cougars may feed heavily on them when they’re available in large numbers. However, cougars, like wolves, don’t survive for long unless large prey is common.

When a cougar kills a large animal, it may feed on it for as much as ten days. Often it will drag its kill into woods or brush where it can conceal it, frequently by covering it, to keep its presence secret from scavengers. By the time a cougar finishes with a carcass, there is amazingly little left. Even the large upper leg bones are devoured, and only the jaws, the lower legs below the “knee” and “elbow” joints, and the stomach remain.

This brings up an interesting point. Researcher Kenneth Logan, at the Hornocker Wildlife Institute, has seen a cougar eat a mouse and expel the stomach—something that one would hardly expect from such a large predator eating such small prey. I’ve noticed that our house cats also leave the stomachs of their prey. Is this a trait shared by all cats? Members of the dog tribe consume the stomachs of their prey, and even clean up those left by cougars. Perhaps this is yet another difference between cats and dogs.

Breeding male mountain lions are highly territorial and keep other males away, while females have overlapping ranges. Thus there is a surplus, nonbreeding cougar population, much as there is with wolves; young male cougars must wait for older males to die or become decrepit with age or injuries before moving into the breeding population.

Cougars only reproduce once every two to three years. Cat-fashion, cougar toms take no interest in raising their offspring; once mating is over, the male and female go their solitary ways. After a gestation of about three months, the females have a litter of kittens, normally two or three but occasionally more. These can be born at almost any time of the year.

As with the young of other cats, the kittens’ eyes are closed for the first ten days. The baby cougars are spotted, and remain so until they’re six months old. By the age of nine months, the young cougars are capable of hunting on their own, but they usually remain with their mother for up to two years.

One of the most astonishing facets of cougar behavior is their vocal versatility. Few would imagine that this great cat could chirp almost like a bird, yet a mother will use such sounds to communicate with her kittens, for example. They also produce fairly elaborate whistling sounds that go up and down the scale. Other cougar sounds are far less musical. One has been described as a rather raspy “ow” sound, which, along with a sort of throaty coughing noise, is probably about as close as this big cat comes to a true roar. Then there are growls and hisses, much like those of a house cat, though considerably louder.

Even this array of sounds fails to encompass the full range of cougar vocalizations. Females in heat utter what some have described as a piercing scream, which Kenneth Logan prefers to call “caterwauling.” He describes this as being much like the cries of a house cat in heat, although considerably louder. Having experienced this caterwauling at close range on a number of occasions, he believes that those who describe it as a high-pitched scream have heard it at a distance, with trees or other obstacles filtering out all but the highest tones. Because cougars are solitary and often live far apart, this loud yowling probably aids the males in locating females in heat.

Finally, cougars have the virtue of being able to purr loudly and contentedly. Logan says he has been in a cage with a purring cougar, and he describes the sound as “thunderous” at that range.

It’s long been an article of faith that cougars don’t attack people. That was never quite true, but cougar attacks in the past were indeed extremely rare. During the past few years, though, the number of cougar attacks on humans has escalated substantially. Three people have been killed by cougars in Colorado, and a number of others have been mauled or stalked in several states within the past five or six years. Though such attacks still don’t represent a major threat to people, they’re nonetheless disturbing.

Cougar experts believe the trend toward more cougar attacks has three causes. First, cougar populations have increased greatly in some areas. Second, large numbers of homes, with their attendant human activities, have invaded major blocks of prime cougar habitat. This situation naturally creates many more opportunities for interactions between people and cougars. Third, halting all cougar hunting in California has created cougar populations there that have little or no fear of humans.

None of this should cause people to have an inordinate fear of cougars. The number of cougar attacks on humans is still very small, representing far less of a threat to human life than lightning or bee stings—to say nothing of automobiles. Nevertheless, in view of the increasing number of attacks, it’s wise for anyone living or hiking in cougar country to know how to handle a confrontation with one of the big predators. State wildlife agencies in the West usually have valuable information on this subject; the California Department of Fish and Game, for example, has an excellent handout called “Living with California Mountain Lions.”

Once widely persecuted as a varmint, and eliminated from the eastern portion of its range, the cougar’s future today looks reasonably bright. Although the big cats are hunted as game animals in several states, hunting is closely regulated and in no way threatens cougar populations. The one serious danger facing the cougar is loss or fragmentation of habitat. As humans continue to encroach on the cougar’s territory, homes and concomitant development such as roads destroy valuable habitat. Still, with large areas of the West set aside in wilderness, national forests, and other public lands, this magnificent big cat should continue to flourish.

21

Three Minus Goldilocks: Black, Brown, and Polar Bears

MYTHS

Bears in national parks and similar places are tame and safe to feed or pet.

Bears in national parks and similar places are tame and safe to feed or pet.

Bears eat mostly meat.

Bears eat mostly meat.

Bears can’t run fast uphill, so a person can escape a bear by running up a steep incline.

Bears can’t run fast uphill, so a person can escape a bear by running up a steep incline.

Most bears den in caves.

Most bears den in caves.

Hibernating bears sleep so soundly that they don’t even awaken when their cubs are born.

Hibernating bears sleep so soundly that they don’t even awaken when their cubs are born.

Black bears hoot, almost like an owl.

Black bears hoot, almost like an owl.

Bears often attack people.

Bears often attack people.

All bears are good tree climbers.

All bears are good tree climbers.

Alaska brown bears are easily the world’s largest bears.

Alaska brown bears are easily the world’s largest bears.

Polar bears are white.

Polar bears are white.

BEARS ARE FASCINATING CREATURES. Although they don’t arouse the hatred and fear engendered by the wolf—after all, the bears in the story of Goldilocks meant well, even if they frightened the little girl—they’re often misunderstood and widely underappreciated. They’re the largest of all terrestrial predators, immensely powerful and, when they choose to be, very fast for short distances.

Our three North American bears are related quite closely, and share many anatomical features and traits, but they also display surprising diversity in a number of ways, such as size, temperament, diet, and habitat.

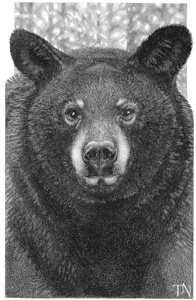

Black bear

THE BLACK BEAR

The black bear

(Ursus americanus)

and its brown phase, the cinnamon bear, are by far our commonest bears. Current estimates of their population run around 750,000, with approximately 100,000 in Alaska alone, so there’s most assuredly no shortage of this species; in fact, black bears are actually increasing in many areas. The black bear is also the smallest of our three native bears: even though a very few extraordinarily big, fat specimens exceed eight hundred pounds, those are no more the norm than seven-foot-two-inch basketball players or 325-pound football linemen are typical of humans. Adult black bears commonly range from 150 to four hundred pounds, with the vast majority three hundred pounds or less.

Normally extremely shy and reclusive, black bears usually flee at the first sign of a human. But these animals can also become habituated to people rather quickly, and therein lies a major problem. Black bears—or, more properly, people fascinated by black bears—are the bane of park rangers and other public lands officials. Despite every warning, ignorant individuals persist in thinking that black bears begging for handouts along roadsides and in parking lots and campgrounds are tame—a sort of hybrid composed of equal parts Yogi Bear, Gentle Ben, and a child’s teddy bear. In fact, these bears are extremely dangerous because, while not tame, they’ve lost their fear of humans.

Every year people are injured, some seriously, when they try to feed bears, despite all the warning signs and lectures. Worse yet, I’ve heard horrific tales from thoroughly reliable sources about people who have tried to take pictures of their children with a bear—and have even attempted to put their child on a bear’s back!

Conflict between black bears and humans in such places as parks and campgrounds is hardly new, although the growing popularity of travel to these spots has certainly exacerbated the situation. In the 1920s, for instance, my mother’s cousin, a civil engineer, headed west to work in the mining industry. After he had reached one of the western states, he stopped to ask directions at a ranger station in a national park.