Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (35 page)

At about two weeks, the pups’ eyes open, and they can hear when they’re about three weeks old. Then, by the time they’re a month old, they begin to leave the den. They begin to eat solid food, and pack members now begin to bring food for the fast-growing pups.

When the pups are about two months old, they’re taken to a rendezvous site. This is a location where the pups can be left safely while the pack members go forth to hunt, then rendezvous at the spot. A rendezvous site features some sort of protection for the pups, such as a crevice in the rocks or extremely dense vegetation. There the pups remain, sometimes exploring for short distances around the site, while the rest of the pack hunts, returning periodically to the pups.

Then, by fall, the pups are big enough to travel and hunt with the pack, and they’re nearly full-grown by the time they’re a year old. Although they’re capable of reproducing by age two, full sexual maturity isn’t achieved until age four or five.

Nowhere do the conflicting views of wolves display themselves more starkly than over the issue of wolf reintroduction. Under the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) held numerous public meetings and hearings in the West, and received testimony in various forms from thousands of citizens. Although predictably polarized for and against wolf restoration, comments heavily favored the former. As a result, the USFWS trapped wolves in Canada and released them at two locations, Yellowstone National Park and the Frank Church–River of No Return Wilderness Area in central Idaho.

Biologically, these transplants have been a howling success (pun intended). There are now more than 150 wolves in a number of packs in the central Idaho area, while the Yellowstone wolf population, counting this year’s crop of pups, stands at about 350. Alpha wolves have mated, and packs have formed in normal fashion, fought over territory, killed each other in territorial battles, and otherwise behaved in similar fashion to wolves in areas where they’ve existed for tens of thousands of years.

Politically, the road has been far rockier. To minimize the fears of ranchers that wolves spreading out from these release sites would decimate their livestock, the USFWS declared these wolf reintroductions “experimental populations.” Under the terms of the Endangered Species Act, this designation allows the flexibility to remove or kill wolves that are preying on livestock and pets.

Two diametrically opposed groups then brought suit to halt and reverse the wolf reintroductions. On the one hand was the American Farm Bureau, unalterably opposed to wolf reintroductions; on the other was a consortium of groups so pro-wolf that they felt the experimental population designation didn’t give sufficient protection to wolves that might naturally disperse into these areas from Canada.

In December 1997 a federal district court judge ruled that the experimental-population designation was illegal because it gave insufficient protection to wolves naturally dispersing into Yellowstone and central Idaho. The judge ordered all reintroduced wolves

and their offspring

to be removed, then stayed his order so that appeals could be filed.

After numerous delays, as of this writing the appeals have yet to be heard. Meanwhile, nearly two years have passed and many more pups have added greatly to the wolf population in these two areas. The judge’s decision was based on what many observers regard as a bizarre interpretation of the Endangered Species Act. Under his interpretation, a dispersing wolf here and there constitutes a “population,” a definition that few believe will be sustained on appeal. Further, the only way to get rid of the several hundred wolves now present would be to kill them, since trying to trap and relocate them would be an extraordinarily difficult task at this point. The likelihood that the American public at this point would stand for the slaughter of all those wolves is about as great as the chances of that famous proverbial snowball!

Depredation on livestock has been relatively light, and lower than projected by the USFWS. Most such depredation remains inordinately controversial, however, because of the antipathy which some hold toward wolves. To put the matter in perspective, losses from wolves in the greater Yellowstone area have been less than one-thousandth of annual losses of cattle and less than one-hundredth of sheep losses. Indeed, a few ranchers have even testified that their losses have diminished with the advent of the wolves. Why? Because wolves largely displace coyotes, and wolves are easier than coyotes to keep away from the sheep.

Several steps have also been taken to compensate ranchers for livestock depredation by wolves. First, problem wolves are either trapped and transported elsewhere or killed. Second, ranchers grazing livestock on public lands have been granted reduced grazing fees to compensate them for such losses. And, third, Defenders of Wildlife, a private organization, reimburses ranchers for losses proven to have been caused by wolves.

It should be noted that trapping and removing problem wolves hasn’t proven very successful. Once wolves have learned how easy it is to kill livestock, they often return or seek other areas where they can prey on cattle and sheep, and these wolves ultimately have to be killed. Moreover, many translocated wolves often die. In either case, most of the problem wolves end up dying soon after their removal. It appears, therefore, that the best solution to problem wolves is simply to kill them in the first place.

Although livestock losses to wolves have been fewer than expected, an occasional rancher has suffered financial loss despite safeguards and compensation. A few have complained that they couldn’t locate livestock that they suspected was killed by wolves, or couldn’t find it in time to prove that wolves were the culprit, so that they could be compensated. This problem is being addressed by putting a radio tag on each calf; when a calf dies, it can be found quickly enough to see whether or not compensation is warranted.

Despite some complaints, the system of killing problem wolves and compensating farmers for losses has worked quite well in Minnesota for a number of years. Clearly, adoption of this system in the West isn’t problem-free, and undoubtedly needs tweaking a bit here and there to fit local conditions, but the difficulties should be manageable in a way that fairly compensates ranchers for losses and yet allows wild populations of wolves to exist.

Now the Northeast seems to be the next likely source of wolf controversy. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is preparing a wolf recovery plan for the region—a plan that could ultimately recommend the release of wolves in remote areas, most likely in northern Maine and in the Adirondack Mountains of New York. Predictably, heated opposition is already lining up, even though the lengthy planning process has hardly begun.

Reaction from New Hampshire was swift, and the legislature passed a law banning the release of wolves within the state. At least part of this reaction was based on fear and sheer ignorance; one legislator even raised the ludicrous specter of packs of wolves attacking tourists and hikers at night! Some farmers’ and sportsmen’s groups are also opposing any wolf release in their respective states.

On the other hand, thirty-one environmental and conservation groups have formed the Eastern Timber Wolf Recovery Network. These include the National Wildlife Federation, which is the nation’s largest private conservation organization, and in aggregate they form a powerful pro-wolf lobby. They have their work cut out for them, however, as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has said that it won’t release wolves on private lands over the objections of the owners. With relatively few large blocks of public land in the Northeast, this policy would greatly complicate any wolf release.

The whole controversy could become academic, however, if wild wolves from Canada infiltrate the northern reaches of the Northeast. Two animals— one definitely a wolf and the other quite likely a wolf—have been killed in northern Maine. Moreover, a Maine hunter and woodsman has seen what he firmly believes is a wolf, and has extensively tracked two or three other equally large animals that he feels confident are wolves.

Some biologists believe that the pattern of infiltration from Canada observed in the West is repeating itself in the Northeast. First there were numerous reports of wolf sightings, they say, and then a pack eventually formed. Others feel that the heavily settled St. Lawrence River Valley, the four-lane highway running through it, and the river itself constitute a nearly insurmountable barrier against any significant southward movement of wolves. An occasional wolf, they assert, won’t be enough to establish a pack in the Northeast.

Only time will tell how conflicting views among the public and contrasting opinions among biologists will ultimately be resolved. The only thing that seems certain is that the budding uproar over wolf restoration in the Northeast is likely to grow a great deal more heated!

No chapter about wolves would be complete without a warning about wolf-dog hybrids. These crosses between wolves and dogs have become increasingly popular—indeed, something of a fad—within the past few years. Although there are exceptions to any rule, owners of wolf-dog hybrids generally fall into two broad categories. The first is the macho type who wants a pet with a macho reputation to match, while the second is the person enamored with the notion of wildness who wants somehow to own a piece of that wildness.

Let me be very blunt about it: wolf-dog hybrids are DANGEROUS! Many owners of these crosses become highly incensed at the idea that their lovely hybrid could cause problems, let alone harm anyone. However, the facts tell a very different story.

The danger is greatest for small children, roughly a dozen of whom have been killed by wolf-dog hybrids in the past few years. Anyone with any kind of disability, even a temporary one, may also be at risk. Wolves by nature constantly try to assert their dominance, and they’re quick to sense weakness in humans; this may lead them to attack in an attempt to become dominant, just as they would with other wolves.

Small children, on the other hand, may for some reason or other appear as prey to a hybrid and awaken its killing instinct. No one knows for certain what triggers these attacks on either adults or children by wolf-dog hybrids, but the frightening thing is that they’re usually lightning-fast and totally unexpected. Very often, attacks are by hybrids that have never before acted vicious in any way.

As a result of numerous attacks, a number of states have passed strict requirements for ownership of wolf-dog hybrids. Typically, the hybrid must be leashed and kept behind heavy-duty fencing that extends a specified distance below the surface of the ground. This latter precaution is to keep the hybrid from digging its way out.

It’s not only the very young or the infirm who have problems with wolf-dog hybrids, either. Wolf expert Elizabeth Duman put it this way: “Very simply stated, any animal that is very much wolf is going to exhibit enough wolf behavioral traits to warrant special handling.” This dictum is borne out nearly every day, as thousands of people who loved the idea of a wolfish pet find that they can’t handle its wolfish behavior.

Some are bitten, though usually not seriously harmed, while others can’t control the animals that are ruining their homes. As a result of these and other problems, humane societies, organizations dealing specifically with wolves, and similar groups are inundated with problem hybrids, most of which have to be euthanized. Even though some wolf-dog hybrids are, and remain, sweet-tempered and biddable, the majority of them cause problems. Don’t acquire one!

Despite the controversy surrounding wolf reintroduction, it clearly is feasible and, many experts would say, desirable in a few places in the United States. Two conditions must be met, however. First, there must be a large, uninhabited area: there are simply too many problems connected with wolves in proximity to humans, their livestock, and their pets to attempt reintroduction in settled areas. Second, wolves that begin preying on domestic animals will often have to be killed. Trapping these individuals and moving them to new locations fails most of the time. Although many wolf lovers bitterly criticize any killing of wolves (the wolf-as-sainted-predator syndrome), those who value this great predator for what it is and are deeply committed to its survival recognize the necessity of this step. As L. David Mech, who has done so much to further wolf survival, summarizes it, “It is unfortunate that some wolves will have to be killed. However, this should be regarded as the necessary price for allowing wolves to live elsewhere.”

With attitudes toward wolves rapidly shifting toward the Good Guy image, even if they sometimes become sloppily and irrationally sentimental, it seems likely that we’ll see more wolves, at least in certain parts of the United States. The real key to the future of this fascinating great predator is habitat preservation. Take away the wild areas, and wolves will vanish. Preserve large blocks of wilderness, and wolves will thrive.

19

Cousins with a Difference: The Bobcat and the Lynx

MYTHS

The lynx is larger and fiercer than the bobcat.

The lynx is larger and fiercer than the bobcat.

Bobcats scream horribly.

Bobcats scream horribly.

IF THESE TWO CATS WERE HUMAN, THEY WOULD SURELY BE REGARDED NOT MERELY AS COUSINS BUT AS

FIRST

COUSINS. So closely related are they that, while most other members of the world’s cat family are lumped into the plebeian genus

Felis,

the bobcat and Canada lynx—plus the nearly identical Eurasian lynx and the Spanish lynx—share their own exclusive genus of

Lynx.

However, just as human first cousins can display great variation, these two short-tailed cats differ widely in build, temperament, habitat requirements, and prey.

Depending on the authority one consults, there are either three or four species worldwide in the genus

Lynx,

and thereby hangs a tale. Scientific names are formulated by scientists known as taxonomists. Taxonomists are specialists in the science of classification; they decide, for example, which family and genus a creature belongs to, and whether or not it should be listed as a distinct species. As in all forms of scientific endeavor, there are differences of opinion among taxonomists, so they may alter a scientific name one year and change it back again another.

This sort of Ping-Pong with the scientific nomenclature of cats has been in full swing in recent years. For a long time the North American lynx was

Lynx

canadensis,

while its bobcat cousin was

Lynx rufus.

Then, several years ago, these two cats lost their distinctive genus and were “downgraded” into the far broader genus

Felis,

becoming, respectively,

Felis canadensis

and

Felis rufus.

But, as the song goes, “The cat came back, it wouldn’t stay away,” and more recently the bobcat and lynx were restored to their former lofty status as the proud possessors of their own highly exclusive genus. That’s not quite the end of the tale, though.

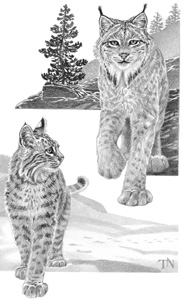

Bobcat; lynx

As one biologist put it, taxonomists can be roughly divided into “lumpers” and “splitters.” In this instance, the lumpers believe that the North American lynx and the Eurasian lynx are a single, circumpolar species,

Lynx lynx.

The splitters, on the other hand, prefer to call our North American lynx

Lynx

canadensis

and the Eurasian brand

Lynx lynx.

In either case, the bobcat remains

Lynx rufus,

and the only other member of the lynx genus, the Spanish or Iberian lynx, continues as an apparently noncontroversial

Lynx

pardinus.

While this debate over names is of absorbing interest to many humans, it seems doubtful that the affected members of the cat family are much concerned about it!

While we ponder the scientific names of these two wild cats, a brief digression seems warranted regarding the scientific name of the house cat—that household pet so familiar to us all. Ever since I can remember, the house cat bore the appellation

Felis domestica—

the domestic cat—but many scientists felt that this name was rather ill-suited to the house cat’s notably independent nature.

As one authority expressed it, “The house cat isn’t domestic—it’s

commensal.”

The term comes from the Latin

mensa,

table, and in this instance means that although house cats deign to share our food, they steadfastly refuse to be owned or told what to do. In short, they aren’t truly domesticated. It’s certainly no accident that the saying “it’s like trying to herd cats” has become a metaphor for a virtually impossible task. In somewhat belated recognition of this rather autocratic bent, taxonomists have now awarded the house cat the truly wonderful title of

Felis cattus.

What could be more fitting?

Members of the genus

Lynx,

however, are most certainly neither domestic nor commensal. Thoroughly wild, these elusive cats are seldom seen or heard. Nevertheless, the lynx and bobcat are important components of our North American wildlife, worthy of deep appreciation for their unique qualities.

The widespread impression that the lynx is larger and fiercer than the bobcat (also known as the bay lynx) is erroneous. The lynx certainly

appears

much the larger of the two; its extremely long legs, huge feet, very thick coat, large jowl tufts, and long ear tufts all lend it an aura of size. When stripped down, though, the lynx is the mammalian equivalent of the owl—surprisingly little weight in comparison to apparent size.

Most lynx weigh in the range of fifteen to thirty pounds, with the low end of that range not much bigger than a large house cat. And, despite all appearances to the contrary, the average bobcat actually outweighs the average lynx. Most bobcats weigh between fifteen and thirty-five pounds, although a very large male will sometimes top forty pounds; as with the lynx, however, many bobcats aren’t much heavier than a big household tabby.

In temperament, too, appearance belies reality. The lynx looks much larger and fiercer than the bobcat, but whenever the two cats encounter each other in the wild, it’s nearly always the less aggressive lynx that gives way.

All of this makes considerable sense when habitat and prey requirements of the two species are considered. The lynx is very much a creature of the boreal forests, where winters are long, the snow soft and deep, and the cold fearfully penetrating. From the Arctic portions of Alaska and the Northwest Territories to all but the northernmost extremity of Labrador, it roams the vast wilderness and endures the harsh winters of the far north. Only in northern bits of the Great Lakes states, parts of the Rocky Mountains, some of the Cascades, and possibly the farther reaches of Maine does this northern denizen reside in the lower forty-eight states.

The lynx’s most prominent features come into sharp focus as wonderful adaptations for survival in this unforgiving northland climate. Consider its fur coat, for example—the pelage that makes its owner look so much larger than it really is. Because of this coat, the brutal Arctic cold presents little problem for the lynx, provided always that it can obtain enough food to fuel its body. It would be hard to find a more magnificent pelt than the long, incredibly soft and dense fur of the lynx. Insulated by that wonderful covering, the lynx can easily withstand the bitter cold so prevalent throughout its range.

Then there are those huge feet—great furry pads about as large as those of a cougar. These act as snowshoes to prevent the lynx from becoming mired in the deep snow of frigid northern winters. Despite these “snowshoes,” however, the lynx often sinks a considerable distance into the dry, powdery snow. Then its long legs come to the rescue.

One of the reasons why the lynx weighs so little in relation to its apparent size is the length of its legs, yet another adaptation for life in the far north. These seem ridiculously long—for a cat, at least—yet they’re invaluable for survival: those long legs prevent its body from dragging deeply in the snow.

All of these adaptations come into play when the lynx pursues its principal food source, the snowshoe hare. Although the lynx will prey on other creatures when hares are scarce, the cat’s ultimate fate is inextricably bound to that of the long-eared, big-footed hare. Indeed, so narrow are the lynx’s food preferences that it dines on hare to the virtual exclusion of everything else as long as hares are abundant. Only out of sheer necessity does the big-footed cat turn to alternative prey.

The aptly named snowshoe hare is notably cyclical, especially the farther north one travels. Hares go through a boom-and-bust cycle roughly every ten years, gradually building up year by year to well-nigh incredible populations in which there seems to be a hare behind every bush, shrub, and tussock. Then, almost overnight, hare numbers plummet so drastically that there’s hardly a hare to be found where previously there were hundreds.

The lynx population, with a lag of a year or two, mirrors the population curve of its favored prey. As hare numbers soar, most female lynx produce an annual litter that averages two kittens, and the kittens have a high survival rate. After the hare population crashes, the number of kittens declines dramatically, and the few kittens born rarely survive.

Nor are adults immune to this sudden shift from superabundance to scarcity, for many lynx starve in the aftermath of the hare’s virtual, if temporary, disappearance. One facet of this phenomenon remains a puzzle to biologists, however: while numerous lynx starve during the great dearth of hares, some individuals appear to remain well fed. How they manage this feat while so many of their fellows starve is a mystery. Perhaps the survivors are more adept at foraging on a variety of prey, such as ptarmigan, squirrels, voles, mice—even carrion. No one knows for sure, although further research may provide answers to this riddle.

Lynx are by no means suited for long-distance pursuit in the sense that, for example, wolves are, but they’ll pursue hares at high speed for moderate distances, and here their long legs and huge feet, which parallel the adaptations of their prey, again prove invaluable. Even in soft, deep snow, the lynx can often run down a hare within a short distance. The contest is hardly one-sided, however, for the lynx frequently fails in its pursuit of the speedy hare.

Lynx, however, like most other cats, are much more stalkers and pouncers than pursuit animals. Their instinct is to conserve energy; a careful stalk and a swift pounce, or an all-out sprint for a relatively short distance, expend far less precious energy than a lengthy chase. Using an even more energy-efficient technique, lynx often simply lie down along hare runs and wait for their prey to come to them.

Lynx mate during January and February—the dead of winter in the northern climes where they reside. Their gestation period is about two months, so the kittens are born, blind and hairless, in March or April. The female gives birth in whatever sort of den the terrain offers. This can be a hollow log, a hole in a tumble of rocks, a space beneath the roots of a large stump, or some similar place that offers shelter from the elements.

Like cats the world over, the male lynx has no interest in family matters once he has mated, and it’s left to the female to raise the kittens in single-parent fashion. Though the kittens are helpless at birth, their eyes open after ten days, and they’re soon rolling and tumbling much like domestic kittens.

After about twelve weeks the kittens are large and strong enough to accompany their mother during her quest for food. As they follow her, they learn by example how to stalk their prey, pursue it, or conceal themselves beside a run to await the approach of a hare. Then, once they’ve received this all-important education, they set out to find their own territories.

North American scientists are only now beginning to study the lynx in anything approaching the detail lavished on many other species. This oversight is partly due to the elusive character of the lynx, its generally inaccessible habitat, and its relatively low population levels. Even the most basic question—how many lynx there are, especially in the lower forty-eight states— hasn’t been answered.