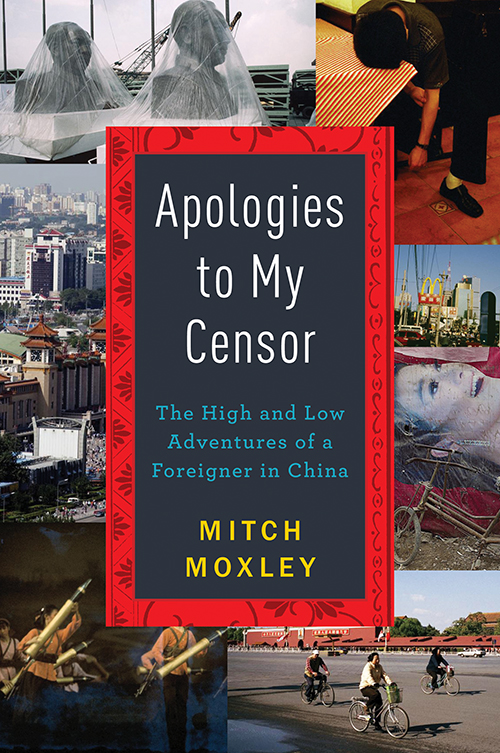

Apologies to My Censor

Read Apologies to My Censor Online

Authors: Mitch Moxley

Apologies to My Censor

The High and Low Adventures of a Foreigner in China

Mitch Moxley

For Mom & Dad

Contents

M

y greatest

fear was about to become reality: sober dancing.

I stood atop a set of stairs at a faux-Italian

outdoor mall in Beijing, my face in full makeup and my hair styled in the weird,

poofy way of urban Chinese, wearing skinny jeans and a short-sleeve black shirt

unbuttoned halfway down my chest. Beside me was a small-time pop star from

Shandong province named Marry (two

r

's), rehearsing

the upcoming shot in a flowing white wedding dress. Next to her was a Chinese

male model with pursed lips and a perfectly trimmed goatee. At the foot of the

stairs awaited the nervous director, a cameraman, and forty-odd pairs of curious

eyes: crew members and passersby, all eagerly anticipating, I was sure, the

disaster that was about to unfold.

The camera started rolling. Beads of sweat trickled

through the stubble on my cheeks like pachinko balls as I descended into a

true-life nightmare.

I started to dance.

A few days earlier, I had been

approached on the street by a stranger and asked to appear in a music video as

the star's European love interest. As random as it might sound to be asked to be

in a music video, ridiculous incidents of this nature are not totally uncommon

in China. I once posed as one of China's 100 “Hottest Bachelors” for a special

Valentine's Day issue of

Cosmopolitan

magazine. The

vetting process was not very thorough, and by “not very thorough” I mean totally

nonexistent: the project's editors had never laid eyes on me before I showed up

for the shoot.

I should mention, however, that I'm not your

typical music video star. I'm a journalist. I'm tall and a bit lanky, and

although I've had my share of movie star fantasies, I can be terribly awkward in

front of a camera. I have certain featuresâsay, a long neckâthat can appear

unusual in pictures and on video. From certain angles my face can seem

cartoonish, and it's often when I'm trying to look cool that I look most uncool.

In the

Cosmopolitan

Valentine's special, I ended up

looking like a vampire in a checkered suit two sizes too small.

Thinking that appearing in a music video might be a

worthwhile story, I agreed under one condition: no dancing. Sober dancing is my

kryptonite. On the rare occasions when I do dance, I break out in a nervous

sweat, swing my arms awkwardly, and buckle at the knees. I'm convinced

everyone's watching me.

Look at the tall loser

freak!

I imagine them all saying.

Now there we were, filming the video's key scene,

my body writhing in awkward, robotic movements. We tried several takes, each

worse than the last. During a break, I pleaded with the director to cut me from

the video entirely and spare everybody the hassle of having to figure out how to

salvage the footage.

They begged for a few more takes. I reluctantly

agreed.

Atop the stairs once again, I looked out at the

eyes staring back to me. I became lightheaded and began to have an out-of-body

experience, where I was able to see an image of myself in my skinny jeans and

unbuttoned black shirt, my hair made up like a bird's nest. “Action!” the

director yelled, and before I could stop, my body contorted itself into a

strange little jig. I forced a stupid grin and pretended to be in love with

Marry as she lip-synched her awful, pitchy song. I could imagine what the video

might look like once edited, and where it might be played, and what my friends

would think if they ever saw it.

As these images of impending doom played in my

mind, I thought: Oh fuck, YouTube.

I

was thirty years old and this was my

life: a series of random China adventures that seemed to stretch on forever.

Toward what, I still wasn't sure.

How did it all happen? I asked myself that question

every day. In fact, I shouldn't even have been there at allâin Beijing, in

China, on the stairs of that outdoor mall.

I came to Beijing in the spring of 2007 to take a

job as a writer and editor for

China Daily

, the

country's only English-language national newspaper at the time. My journey to

China was by accident. One freezing afternoon in Toronto a few months

earlierâdepressed, bored, failing as a writer, and unsure of where my life was

headedâI opened an online journalism job board and noticed a posting for a

position at a government-owned newspaper in Beijing I'd never heard of. I had

never imagined going to China, but anything was better than the state I was in.

So I applied, and a few months later, after a writing test and a brief phone

interview, I was offered a one-year contract.

In China, everything was happening. The economy was

booming, the Olympics were on the horizon, and Beijing was being transformed

into a world-class city overnight.

China Daily

was

changing, too. Somewhere in the bowels of the

China Daily

headquarters in Beijing, someone had decided the paper needed some

sprucing up before the Games. Money flowed in, the paper was redesigned and

expanded, and, in an effort to improve the quality of the writing, the

management recruited a growing team of “foreign experts” (the official wording

on our visas) from all corners of the English-speaking world. When I arrived in

mid-April, there were three dozen of us, mostly new arrivals. We were going to

play a big part in the “new”

China Daily

, they told

us. We were important.

Before I left Canada for Beijing an e-mail landed

in my inbox from a friend's father, who was working in Chinese state media at

the time. “It's important to know that journalism here ain't quite the same as

over there,” he wrote. “Not by a long shot. It's journalism with âChinese

characteristics.' ” Shortly after, I received another message from an American

editor at

China Daily

. “Just so you don't have any

illusions about this,

China Daily

is a State-owned

newspaper, as is all media in China. That means you would be dealing with two

ultimate bosses: (1) The Information Office of the State Council and (2) the

Propaganda Department of the Communist Party of China.”

In other words, despite my official position as

writer and editor for

China Daily

's business

section, I was essentially accepting a job as a propagandist for the government

of the People's Republic of China.

M

y original plan was to stay for just

over a year, work out my contract, have some fun, stick around for the Olympics,

and return to normal life. China was meant to be a break. A chance to

reboot.

Almost four years later, I was dancing like a

robotic idiot in a Chinese music video, and self-admittedly addicted to the

random, chaotic nature of expatriate life in China. Normal life had most

definitely

not

resumed. Among other adventures, I

had crisscrossed the country doing journalism, sat front row to the Olympics,

posed as a fake businessman, indulged in many a booze-fueled night, and paid to

feed a goat to a hungry lion. Along the way I learned that there is no such

thing as normal life for a foreigner in this crazy, exhilarating, intoxicating

nation. You might settle into a routine, and the things around you start to seem

ordinary and mundane, but then you blink and find yourself in the middle of a

surreal situation, such as running hand in hand through an imitation Italian

mall with a wannabe pop star. You remember that you're in China, that you're at

the new center of the universe.

Friends of mine in China often compared our

foreigner experience to Peter Pan's Neverland: a fantasyland where you never

really have to grow up, and if you're not careful, you might never leave. I was,

like many others, one of the Lost Boys of Chinese Neverland. By the fall of

2010, when in the course of a few weeks I filmed a music video, traveled the

length of China by train, almost died hiking on a mountain, and fielded calls

from Hollywood producers over an article I wrote, I wondered if I would ever go

home, or if I was lost in China forever.

The country had changed me. I was, in ways both

figuratively and literally, a different person from the one who arrived in

China. I'm shy in front of a camera. I don't smile in pictures. I certainly

don't dance. The person in the video wasn't the man who stepped off the plane in

Beijing in the spring of 2007. That man, when asked to star in a music video,

would have said something along the lines of . . . “

Hell

no.”

I was the person China had helped create.

I was Mi Gao. Tall Rice.

D

uring

those first jet-lagged days in Beijing, three and a half years before, I would

wake early, make a cup of instant coffee, and watch the spectacle unfolding

outside my kitchen window. On the basketball courts across from my apartment,

several hundred middle school students stood in rows wearing matching blue and

white tracksuits and lazily swung their limbs in unison as horrible Chinese pop

music blasted from the loudspeakers. If there was ever a more half-assed display

of mass calisthenics, I'd never seen it.

A coach hollered commands through a megaphone while

teachers in baggy trousers and sports jackets did laps on the track. On the

brick wall beside the basketball courts, words painted in English read, Unite.

Diligent. Progress. The whole display was astonishing. I took pictures on my

cell phone camera for future reference, sipped coffee, and soaked in the

strangeness of it all.

C

hina

wasn't my first foray into life abroad. In the fall of 2005, I finished a

contract with a newspaper in Toronto and set off to work as a freelance writer

in Asia. Earlier that year, I'd taken a three-week vacation to visit my

childhood friend Will in Nagoya, Japan, where he was working as an English

teacher. During that trip I managed to sell a number of stories to newspapers

and magazines at home. Freelancing seemed promising, and I left Toronto that

September confident that I could easily survive overseas.

That fall, I traveled to Vietnam, Thailand, and the

Philippines, freelancing a few articles for foreign publications. Between each

trip, I would return to Japan and stay at Will's place. We would party all

weekend, recover from our hangovers by watching movies, relaxing in

onsen

bathhouses, or going to the beach, and then do

it all over again. During one of our more epic nights, an all-night affair in

Nagoya, we set off a fire extinguisher in an elevator, covering ourselves in

salty-tasting pinkish powder as the door closed on us. Life was great.

But things started to sour shortly after Christmas.

I realized there was no way I could sustain myself on the pathetic earnings of a

freelance writer, especially when I was blowing wads of cash partying until 7

a.m. in one of the world's most expensive countries, and jet-setting across Asia

to write stories I wouldn't be paid for until months afterward. I decided to

settle in Nagoya and find work as an English teacher. I soon learned, however,

that they didn't hand these jobs out at the airport as I had originally thought.

Most of the turnover at English schools occurred during semester breaks, and I

was looking during the middle of the semester. Job opportunities were scarce,

and several weeks went by with not so much as an interview. My parents were

putting cash into my account to keep me afloat. (This, sadly, would become a

recurring theme in my life over the next few years.)

Other parts of my life were disintegrating as well.

I had a girlfriend back in Canada, and our relationship was slowly drawing to a

close. So it was with mixed emotions that I left for Japan that September. “I

need to do this,” I told her a few days before I left. And I didâI needed to

travel while I was still young, to see if I could make it as a writer. Although

we were officially broken up, we talked and e-mailed regularly while I was away,

and we ended up in a relationship purgatory where neither of us really knew what

was going on but we were too afraid to talk about it. The uncertainty weighed on

me every day I was abroad. Over time, my calls home grew more infrequent, my

e-mails shorter and more distant until it became clear I was losing her, at

which point I began to panic.

Meanwhile, I developed a mysterious infection

during my trip to the Philippines over Christmas that caused a rather horrible

case of acne, something I'd never had in my life. Acne combined with a looming

quarter-life crisis is an unfortunate and miserable combination. By mid-January,

back in Japan, I was sleeping until noon, drinking too much, and putting very

little effort into finding work. I showed up to one interview hungover and half

an hour late, and I wasn't able to answer a question about the grammatical

difference between “I ate a hamburger” and “I have eaten a hamburger.” When I

got turned down for a job teaching kindergartners at a school inexplicably

called the Potato Academyâdespite a master's degree and a once-promising career

in journalismâI decided it was time to cash in my chips and head home.

When I returned to Toronto, things didn't get much

better. I spent the summer subletting a room in a house full of crazies fit for

a sitcom. I was working as a freelance reporter, and after a few months of

writing business articles I didn't care about and wandering around alone,

counting the cracks in the pavement, I figured this must be the loneliest

profession on earth.

Most days I sat alone in coffee shops with my

laptop open on the table in front of me, back hunched, struggling to find the

motivation to perform even basic work-related tasks, such as opening a Word

document. Sometimes the thought of walking from my apartment to the coffee shop

was too draining, and I would work in my tiny third-floor room, which had a

slanted roof and no air-conditioning. Many mornings, I didn't bother to get

dressed. I checked my e-mail obsessively, because the Internet seemed to be my

only companion. The solitude, the apartment, the heat, the roommatesâI was

slowly suffocating.

My girlfriend and I made a valiant effort to make

it work when I got back to Canada, but we were running on fumes. We tried out

all of our little inside jokes and old quirks, but they felt forced now. I was

twenty-six and terrified of domestic life: dinner parties with other couples,

weekly softball games, a neighborhood pub filled with grumpy boozehounds,

kidsâ

kids!

I wasn't ready for any of that, and

neither was she. We loved each other, but by mid-July we were officially

done.

My social life, meanwhile, had diminished greatly

from the last time I lived in Toronto. As a freelancer, working alone, I had

fallen off my friends' radarânot that I was trying very hard to engage with

anybodyâand most nights after spending the day in my own head, I would watch

episodes of

Entourage

, lying in bed in the throbbing

heat of my claustrophobic room, noting the many discrepancies between Vincent

Chase's life and my own, wondering where it all went wrong.

I began to exercise obsessively to sweat out my

anxiety. I went to the doctor even if it was only a minor ailment (thank you,

Canadian health care), just to fill my day. I started to see a therapist and do

yoga, trying in vain to clear my head. I sometimes replied to personal ads on

Craigslist to kill time. I did drugs on weekends whenever they were around, as a

temporary balm for my hurting brain. I was twelve thousand dollars in debt and

earning not much more than the summer in college when I worked as a dishwasher,

which now ranked as only the second-most demoralizing period of my life.

O

ne

morning in the winter of 2007, I was sitting in a Starbucks in Toronto working

on a story when my cell phone rang. It was a long-distance number I didn't

recognize. On the other end was an American who said he worked as an editor at

China Daily

in Beijing. It had been months since

I'd submitted my résumé and weeks since I wrote the editing test. I assumed

they'd forgotten about me.

“The bosses were impressed with your editing test,”

the man said. “I can't say for sure, but it looks good.”

I could feel my heart hammering inside my chest but

tried to sound composed on the phone. “That's, that's . . . great

news,” I said. He asked me a few questions about my experience, told me a little

about the job, and said to expect an e-mail shortly.

Over the next few days, I checked my e-mail

constantly, and when the offer finally came, three weeks later, I was ecstatic.

One-year contract, accommodation, plane ticket each way. I was in a coffee shop

and it was blizzarding outside. I wanted to laugh at the swirling snow and its

attempt to keep me rooted and miserable in Toronto. I bit my fist, barely able

to wrap my head around the idea of moving to Beijing. I was going to do it right

this time, I told myself. Not like Japan. I was going to make this trip

count.

After the initial euphoria faded, doubts crept in.

Despite the terrible year I'd had, I couldn't help but wonder if

China Daily

was a step in the wrong direction. Based

on the warnings that soon began landing in my inbox from foreign editors, it

didn't seem like what they were doing over there was

journalism

exactly, and being a journalist was the only thing I had

ever wanted to be.

As a kid, I would sit in my basement penning tales

of sporting glory and intergalactic adventure, a long-haired and ear-pierced

version of my young self in the role of protagonist. In high school, I interned

at a local weekly paper, writing for the sports section, and during my

undergraduate studies I worked at my university's student newspaper. I loved it.

Journalism, and writing in general, gave me an identity. I went on to do a

master's degree in journalism, and during my course I interned at a newspaper in

Toronto called the

National Post

, where I continued

to work after graduation.

My dream was to live abroad and write long-form

magazine articles and books, but I was realistic enough to know that those

things wouldn't come right away. At the

National

Post

, I was placed in the business section, and

although I gave it my best (at least at first), it became clear that a career as

a business reporter was not my calling. I wrote stories about investing although

I had no investments and no interest in investing. I reported on dividends and

bonds and EBITDA and interest rates, without truly understanding what any of

those terms meant. I was perhaps the world's most inadequate business reporter,

and toward the end of my contract it began to show. I made small mistakes,

rarely pitched stories to my editors, and whined incessantly about my job to

anyone who would listen.

I grew anxious to get out into the world and do the

writing I wanted to do. When I eventually left the paper and traveled to Asia in

the fall of 2005, I wrote a few magazine articles that stirred my passions,

including a dozen-page magazine feature about the legacy of Agent Orange in

Vietnam. This, I thought, is what I want to do. I wanted

big

stories, stories I could live and feel, stories that would make

a difference, stories that would take me out of an office and into places I

never knew existed.

But despite a few successes, I never figured out

how to make freelance writing sustainable on that first trip to Asia, and by the

time I was back in Toronto I was writing business articles again, only now I was

doing it for half of what I earned at the

Post

. I

had envisioned that at this stage of my career I would be writing for

GQ

or

Esquire

from jungle

war zones and sinful foreign metropolises. Instead, I was writing weekend

features about how to get a better deal on your cell phone plan.

China was a chance at redemption. In the days after

I was offered the job, I pictured myself cracking A-list publications, maybe

even writing a book about my experiences at

China

Daily

.

At the same time, I had serious doubts. I didn't

know the language. Didn't know much about the city or country, and I had no

friends waiting for me. What if I hated Beijing? What would the job be like?

Would I even be able to freelance while working at

China

Daily

? Would I be able to make it work? Or would I be back in Toronto

within a year, my tail between my legs, feeling like a catastrophic loser

again?

I

couldn't sleep the weeks before I left for Beijing, lying awake, obsessing over

nothing. I had trouble focusing, my mood oscillating between near exhilaration

at moving across the world and a crushing fear that I was making a terrible

decision. Friends and family said it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, that

it would all work out, etc. I wanted to believe them, but moving to

China

? To work for a government newspaper? It seemed

so ridiculous.

One day, struggling to finish a story, I walked up

the street to a bookstore to buy a Beijing guidebook. I was in a fog during the

walk, oblivious to the frozen city around me. I sat down in the store with a

couple of different guidebooks, and flipping through Lonely Planet's

Best of Beijing

I stumbled across a section called

“Newspapers & Magazines.”

“The Chinese government's favorite English-language

mouthpiece,” it read, “is the

China Daily

.”

I opened the

Rough Guide to

China

and searched for mention of my new employer.

China Daily

was good for local listings, the

Rough Guide

said, but “the rest of the paper is

propaganda written in torrid prose.”

My heart, already weighed down, sank to the

pavement.

I

had

second thoughts up until I stepped onto the crowded Air Canada flight bound for

Beijing, at which point it was too late to change my mind.

The next morning, I sipped a cup of instant coffee,

exhausted but relieved that I was finally there, in Beijing, China, watching

kids outside my apartment window perform lazy morning exercises as I tried to

make sense of the words, painted on a brick wall,

UNITE. DILIGENT. PROGRESS.